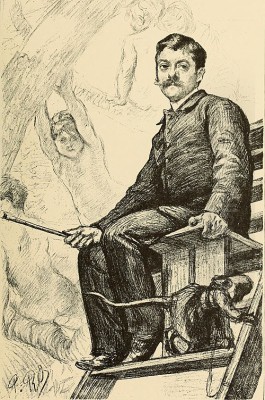

Aimé-Nicolas Morot stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century French art, a painter and sculptor who masterfully navigated the prevailing currents of Academicism while infusing his work with a potent strain of Realism and Naturalism. His career, marked by prestigious awards and influential teaching positions, reflects both the strengths and the evolving nature of the French art establishment in an era of burgeoning modernism. His dedication to anatomical accuracy, dramatic compositions, and evocative storytelling earned him considerable acclaim during his lifetime.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Nancy

Born on June 16, 1850, in Nancy, a city in the Grand Est region of northeastern France, Aimé-Nicolas Morot was the son of François-Aimé Emmanuelle Morot and Catherine-Elisabeth Manzius Estey. His birthplace at 4 rue d'Amerval provided the initial backdrop for a life that would become deeply enmeshed in the world of art. From an early age, Morot displayed a proclivity for the visual arts, pursuing foundational studies in drawing, oil painting, and intaglio printmaking at the Nancy State High School. This early training laid the groundwork for his technical proficiency.

Seeking to further hone his talents, Morot made the pivotal move to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He gained admission to the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of French Academic tradition. There, he entered the studio of Alexandre Cabanel, one of the most celebrated and influential academic painters of the Second Empire and early Third Republic. Cabanel, known for works like The Birth of Venus (1863), epitomized the smooth, idealized style favored by the Salon.

However, Morot's tenure in Cabanel's bustling atelier was reportedly short-lived. Finding the environment too noisy and perhaps creatively stifling for his developing sensibilities, he sought a more independent path to artistic development. This led him to the Jardin des Plantes, the main botanical garden in France, which also housed a menagerie. Here, away from the structured confines of the academy, Morot dedicated himself to the close observation and sketching of animals. This period of self-directed study proved crucial, particularly for his later renowned depictions of animals, imbued with a remarkable sense of vitality and anatomical correctness.

The Path to Recognition: Prix de Rome and Salon Success

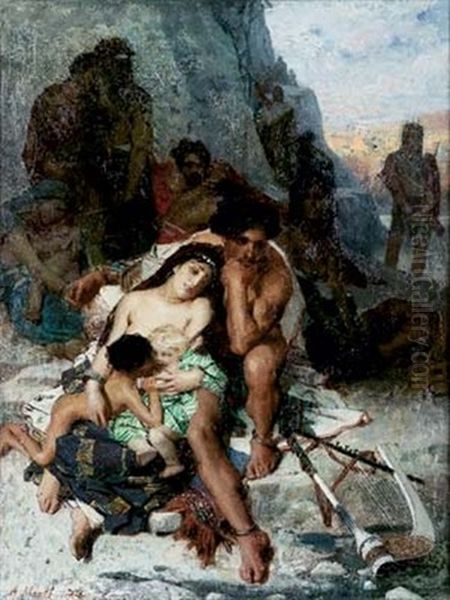

Morot's dedication and talent soon began to yield significant recognition. In 1873, at the age of 23, he achieved one of the most coveted accolades for a young French artist: the Prix de Rome for painting. This prize, awarded by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, granted him a scholarship and a residency at the French Academy in Rome, located in the Villa Medici. His winning painting, La Captivité des Juifs à Babylone (The Babylonian Captivity), demonstrated his mastery of historical painting, a genre highly esteemed by the Academy. Such works required not only technical skill but also the ability to convey complex narratives with clarity and dramatic force, often drawing on biblical or classical themes.

The Prix de Rome was a significant launching pad for an artistic career, and Morot capitalized on this success. Upon his return from Rome, he became a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and the most important venue for artists to gain public and critical attention. His Salon debut marked the beginning of a consistent presence, where his works were often met with positive reception.

His skill was further acknowledged with a second-class medal at the Salon of 1877. This period saw him producing works that solidified his reputation as a painter of considerable technical prowess and dramatic flair. He was adept at capturing textures, from the sheen of animal fur to the gleam of armor, and his compositions were often dynamic and engaging.

The Zenith: Le Bon Samaritain and Academic Prominence

The year 1880 marked a high point in Morot's career with the exhibition of Le Bon Samaritain (The Good Samaritan) at the Paris Salon. This powerful and unflinching depiction of the biblical parable was a triumph. The painting was lauded for its stark realism, its dramatic intensity, and its masterful rendering of human and animal anatomy. Morot’s portrayal of the suffering victim and the compassionate Samaritan was devoid of excessive sentimentality, instead conveying the scene with a raw, almost brutal honesty that resonated with the growing influence of Naturalism in art and literature, championed by figures like Émile Zola.

Le Bon Samaritain was awarded the prestigious Medal of Honor at the Salon, a significant achievement that placed Morot at the forefront of contemporary academic painters. It was particularly noteworthy as it reportedly triumphed over other significant works, including Jules Bastien-Lepage's Joan of Arc Listening to the Voices and Fernand Cormon's Cain. Bastien-Lepage was himself a leading figure in the Naturalist movement, known for his plein-air depictions of rural life, while Cormon was gaining fame for his dramatic prehistoric scenes. Morot's success in this competitive environment underscored the impact of his particular brand of academic realism.

This acclaim led to further honors and responsibilities. Morot was appointed a professor at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the very institution where he had briefly studied under Cabanel. This position allowed him to influence a new generation of artists, passing on the rigorous training and artistic principles he embodied. He also received the Legion d'honneur, one of France's highest orders of merit, specifically for another significant religious work, Le Martyre de Jésus-Christ (The Martyrdom of Jesus Christ), further cementing his status within the French art establishment.

Artistic Style: Academicism, Realism, and Naturalism

Aimé-Nicolas Morot's artistic style is best characterized as a sophisticated blend of Academicism, Realism, and Naturalism. Rooted in the rigorous training of the French academic tradition, his work always displayed a high degree of technical finish, compositional balance, and attention to anatomical accuracy. This foundation was clearly inherited from the lineage of artists like Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose emphasis on line, form, and historical subject matter shaped the École des Beaux-Arts curriculum.

However, Morot was not merely a slavish follower of academic convention. His independent study, particularly of animals at the Jardin des Plantes, instilled in him a deep appreciation for direct observation and a commitment to depicting the natural world with fidelity. This aligned him with the broader Realist movement, which had been pioneered by artists like Gustave Courbet, who sought to portray contemporary life and ordinary people without idealization.

Furthermore, Morot's work shows the influence of Naturalism, a literary and artistic movement that emerged in the latter half of the 19th century. Naturalism, often seen as an intensified form of Realism, emphasized scientific objectivity, determinism, and often focused on the harsher aspects of life. Morot's unvarnished depictions, particularly in works like Le Bon Samaritain, with their focus on physical suffering and raw emotion, reflect this Naturalist sensibility. He sought an objective, almost documentary truth in his subjects, whether they were historical, religious, or scenes of contemporary life.

His specialization in animal painting (animalier art) and military subjects allowed him to showcase his meticulous attention to detail and his ability to capture movement and drama. Artists like Rosa Bonheur had already elevated animal painting to a high art, and Morot continued this tradition with his own powerful portrayals. His battle scenes and depictions of cavalry, such as Rezonville (1886), were celebrated for their dynamism and accuracy, appealing to a public fascinated by military history and heroism, especially in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War. He also produced numerous portraits and classical figure paintings, demonstrating his versatility across genres.

Beyond the Canvas: Sculpture and Monumental Decoration

While primarily known as a painter, Aimé-Nicolas Morot was also a gifted sculptor. His three-dimensional works, often in bronze, displayed the same commitment to anatomical precision and expressive power found in his paintings. This facility in multiple media was not uncommon for academically trained artists of the period, who were expected to possess a broad range of skills. His sculptures, though perhaps less numerous than his paintings, contributed to his overall artistic reputation.

Morot also participated in the grand tradition of monumental decoration, a significant aspect of public art in the French Third Republic. Following the destruction of the Hôtel de Ville (Paris City Hall) during the Paris Commune in 1871, its reconstruction involved commissions for numerous artists to adorn its interiors. Morot was among those selected, contributing to the lavish decorative schemes that celebrated French history, culture, and republican values. One notable work was his fresco Les danses françaises à travers les âges (French Dances Through the Ages), completed around 1894 for the Salon des Fêtes in the Hôtel de Ville. Such large-scale mural projects required a different set of skills, including the ability to work on an architectural scale and to create compositions that harmonized with their surroundings. Other artists involved in such public commissions included figures like Puvis de Chavannes, known for his serene and allegorical murals.

Relationships with Contemporaries

The Parisian art world of the late 19th century was a vibrant and often competitive milieu. Morot, as a prominent academic artist, interacted with many of the leading figures of his time. His early teacher, Alexandre Cabanel, and fellow academic luminaries like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Léon Bonnat, represented the established order, often dominating the Salon juries and official commissions.

Morot maintained a particularly close relationship with Jean-Léon Gérôme, who was not only his father-in-law (Morot married Gérôme's daughter, Suzanne) but also a significant artistic influence and mentor. Gérôme, renowned for his meticulously detailed historical scenes, Orientalist subjects, and sculptures, shared Morot's commitment to academic precision and dramatic narrative. Their personal and professional connection likely provided Morot with considerable support and guidance. They were known to exhibit together and mutually support each other's artistic endeavors.

His success with Le Bon Samaritain placed him in direct, albeit respectful, competition with artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage and Fernand Cormon. Bastien-Lepage, with his Naturalist depictions of rural life, was a critical darling, while Cormon was making a name for himself with dramatic historical and prehistoric scenes. The Salon was the arena where these different artistic visions vied for attention and acclaim.

Morot also engaged in collaborative projects, such as illustration work, which brought him into contact with other artists, including, according to some sources, figures like Eugène Boudin, though Boudin is more famously associated with pre-Impressionist marine landscapes. The network of artists in Paris was extensive, involving not only painters and sculptors but also illustrators, printmakers, and decorative artists.

While Morot operated firmly within the academic tradition, this was also the era of the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent van Gogh were challenging the very foundations of academic art, though their widespread acceptance would come later. Morot's career unfolded against this backdrop of artistic ferment, where traditional values coexisted, often uneasily, with radical innovation.

Personal Life, Later Years, and the "Hameau d'Alain"

Aimé-Nicolas Morot's personal life was intertwined with his artistic pursuits. His marriage to Suzanne Gérôme, daughter of the esteemed Jean-Léon Gérôme, further solidified his position within the Parisian art elite. Suzanne was reportedly a supportive partner, sometimes involved in his artistic activities. The couple had a daughter, Denise Morot, who would later marry the playwright Jean Richepin.

For many years, Morot and his family maintained a residence and studio in Dinard, a coastal village in Brittany. This retreat, known as the "Hameau d'Alain" (Alain's Hamlet), likely provided a tranquil environment for creation, away from the bustle of Paris. Brittany, with its rugged landscapes and distinct cultural traditions, had long attracted artists, including Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard who worked in Pont-Aven. While Morot's style differed greatly from the Synthetism of the Pont-Aven School, his time in Dinard undoubtedly offered fresh inspiration and a different pace of life.

Extensive personal documents, including letters, diaries, and manuscripts, are said to exist, offering potential insights into his private thoughts, his artistic process, and his interactions with the broader cultural figures of his time. These records, if fully explored, could provide a richer understanding of the man behind the art.

In his later years, Morot's artistic output reportedly diminished due to declining health. This is not uncommon for artists who maintained a physically demanding practice throughout their lives. Despite these challenges, he remained a respected figure in the art world. Aimé-Nicolas Morot passed away on August 12, 1913, in Dinard, at the age of 63, leaving behind a significant body of work.

Legacy and Market Reception

Aimé-Nicolas Morot's legacy is primarily that of a highly skilled and successful academic artist who excelled in historical, religious, and animal painting. His works are held in various French museums, including the Petit Palais in Paris and regional museums, testifying to his importance in his era. His paintings, characterized by their technical polish, dramatic compositions, and realistic detail, were highly esteemed by the Salon juries and the public of his time.

The market reception for Morot's work during his lifetime was strong, as evidenced by his numerous awards, commissions, and his professorship. In the decades following his death, like many academic artists of the 19th century, his reputation experienced a period of relative obscurity as modernist art movements came to dominate critical discourse. Artists like Bouguereau, Gérôme, and Cabanel, once titans of the art world, saw their work dismissed by critics who favored the avant-garde.

However, in more recent decades, there has been a scholarly and curatorial re-evaluation of 19th-century academic art. Art historians now recognize the technical mastery, cultural significance, and distinct aesthetic achievements of these artists. Morot's works, when they appear at auction, can command respectable prices, particularly his large-scale Salon paintings or his finely rendered animal subjects. His Le Bon Samaritain remains a key example of the powerful fusion of academic technique and Naturalist observation that characterized a significant strand of late 19th-century French painting.

Conclusion: An Enduring Academician

Aimé-Nicolas Morot was a product of his time, an artist who achieved considerable success within the established structures of the French art world. He masterfully synthesized the rigorous discipline of academic training with a keen observational eye and a flair for dramatic narrative. His contributions to historical painting, religious art, animal depiction, and monumental decoration were significant. While the tides of taste shifted towards modernism, Morot's dedication to his craft and his ability to create compelling, technically brilliant works ensure his place as a noteworthy figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century European art. His career reflects the enduring power of academic realism even as new artistic languages were being forged around him.