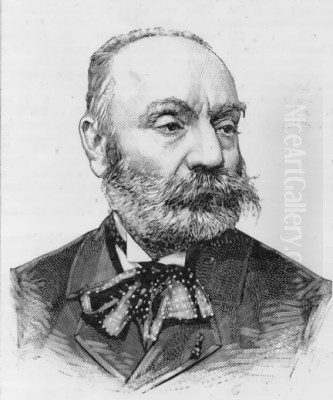

Gustave Clarence Rodolphe Boulanger (April 25, 1824 – September 22/23, 1888) stands as a significant figure in 19th-century French academic art. A painter renowned for his classical and Orientalist subjects, Boulanger navigated the Parisian art world with considerable success, embodying the prevailing tastes and artistic standards of his era. His career, marked by prestigious awards, influential teaching positions, and a steadfast commitment to academic principles, offers a fascinating window into a period of artistic transition and fervent debate. Though later overshadowed by the rise of Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements, Boulanger's contributions to the Neo-Grec style and his evocative depictions of historical and exotic scenes merit renewed appreciation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris in 1824, Gustave Boulanger's artistic inclinations emerged at a young age. The French capital was then the undisputed center of the Western art world, a vibrant hub of creativity and rigorous training. Aspiring artists flocked to the city, eager to learn from established masters and compete for recognition within the highly structured academic system. Boulanger was no exception, and his formal artistic education began under the tutelage of prominent figures who would shape his technical prowess and thematic interests.

He initially studied with Pierre-Jules Jollivet, a painter known for his historical and genre scenes, and then entered the studio of Paul Delaroche at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in 1846. Delaroche was a master of historical painting, celebrated for his meticulously rendered and dramatically charged depictions of events from French and English history. His emphasis on historical accuracy, careful composition, and polished finish left an indelible mark on his students, including Boulanger. Another key influence during this formative period was Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, a painter famed for his incredibly detailed small-scale historical and military scenes, whose precision was legendary.

Boulanger's time at the École des Beaux-Arts was crucial. This institution was the bastion of academic art in France, upholding a strict hierarchy of genres—with history painting at its apex—and emphasizing mastery of drawing, anatomy, and classical principles. Here, he also studied alongside, or was taught by, figures like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jules Joseph Lefebvre. Gérôme, only slightly older than Boulanger, would become a close associate and a fellow leading exponent of both the Neo-Grec and Orientalist styles. Lefebvre, another highly respected academic painter, particularly known for his idealized female nudes and portraits, also played a role in Boulanger's development and later became a teaching colleague.

The Coveted Prix de Rome

The ultimate ambition for many students at the École des Beaux-Arts was to win the Prix de Rome, a prestigious scholarship that allowed laureates to study at the French Academy in Rome for several years. This prize was not merely an honor; it was a significant career catalyst, often ensuring future state commissions and official recognition. The competition was famously rigorous, demanding exceptional skill in historical or mythological painting.

In 1849, at the age of 25, Gustave Boulanger achieved this coveted distinction with his painting Ulysses Recognized by Eurycleia. The subject, drawn from Homer's Odyssey, depicts the poignant moment when Ulysses, disguised as a beggar upon his return to Ithaca after the Trojan War, is recognized by his old nurse Eurycleia, who notices a familiar scar on his leg while washing his feet. Boulanger's treatment of the scene demonstrated his mastery of classical composition, anatomical precision, and expressive narrative, all hallmarks of academic excellence. The painting was lauded for its skillful execution and emotional depth, securing him the journey to Rome. This success was a testament to the quality of his training under Delaroche and his own burgeoning talent.

Italian Sojourn and the Neo-Grec Influence

The years spent in Italy, from roughly 1850 to 1854, were profoundly influential for Boulanger. Residence at the Villa Medici, home of the French Academy in Rome, provided him with unparalleled access to the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. He immersed himself in the study of ancient Roman and Greek art, architecture, and daily life, an experience that would deeply inform his subsequent work. The archaeological discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum were particularly captivating for artists of this generation, offering vivid glimpses into the domestic world of the ancients.

During his time in Rome, Boulanger was part of a circle of artists who were developing a new interpretation of classical themes, which came to be known as the Neo-Grec (or Néo-Grec) style. This movement, spearheaded by artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Jean-Louis Hamon, and Henri-Pierre Picou, sought to move away from the stern, heroic Neoclassicism of Jacques-Louis David and his followers. Instead, the Neo-Grecs focused on more intimate, anecdotal, and often charming scenes of everyday life in ancient Greece and Rome. Their works were characterized by meticulous archaeological detail, a refined and polished technique, and a lighter, sometimes playful or sentimental, tone.

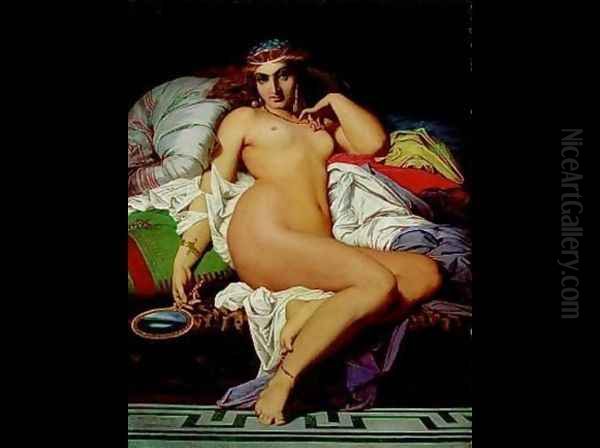

Boulanger's painting Phryne (1850), created during his early years in Rome and now housed in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, is an early example of his engagement with these emerging trends. Phryne was a famous hetaira (courtesan) of ancient Greece, renowned for her beauty and her association with the sculptor Praxiteles. Boulanger’s depiction is sensuous yet restrained, showcasing his skill in rendering the female form according to classical ideals, combined with a careful attention to historical setting.

Rise to Prominence and Orientalist Pursuits

Upon his return to Paris, Boulanger began to establish his reputation through regular submissions to the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. His works, often reflecting his Neo-Grec sensibilities, found favor with critics and collectors. He received a second-class medal at the Salon of 1857 for Caesar at the Rubicon, a powerful historical composition that demonstrated his ability to handle large-scale, dramatic subjects in the grand academic tradition.

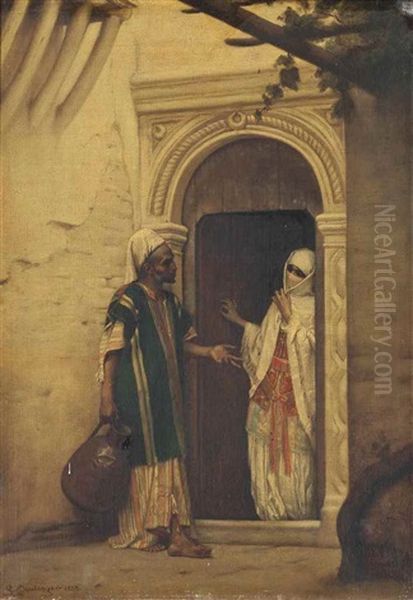

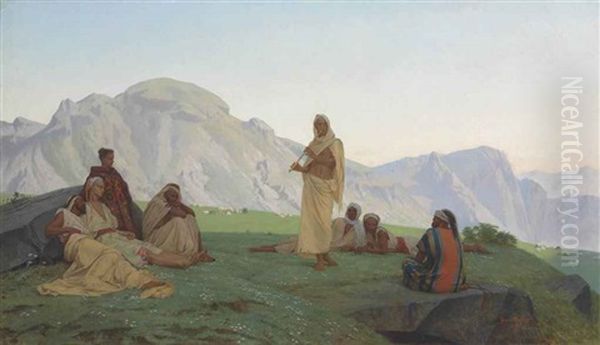

Alongside his classical subjects, Boulanger, like his contemporary Gérôme, was drawn to Orientalism. This artistic and cultural phenomenon, fueled by European colonialism and a romantic fascination with the "Orient" (primarily North Africa and the Middle East), became immensely popular in the 19th century. Artists traveled to these regions, sketching and collecting artifacts to create vivid, often highly detailed, and sometimes romanticized or stereotyped, depictions of exotic lands and peoples.

Boulanger undertook several journeys to North Africa, particularly Algeria, starting in 1845 even before his Prix de Rome. These travels provided him with a wealth of firsthand material for his Orientalist paintings. He was keen on ethnographic accuracy, meticulously rendering costumes, architecture, and daily customs. Works like Deux arabes assis (Two Seated Arabs, 1870) and numerous other scenes of Arab markets, street life, and domestic interiors showcase his observational skills and his ability to capture the unique atmosphere and light of the region. His Orientalist paintings, much like Gérôme's, combined precise realism with a sense of the exotic, appealing to the European public's appetite for such imagery. Other notable Orientalist painters of the era, such as Eugène Fromentin, Ludwig Deutsch, and Rudolf Ernst, each brought their own perspective to these subjects, but Boulanger's work was distinguished by its academic polish and careful composition.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Boulanger's oeuvre is characterized by a consistent dedication to historical and mythological accuracy, combined with a refined aesthetic. His paintings often tell a story, engaging the viewer with carefully constructed narratives and expressive figures.

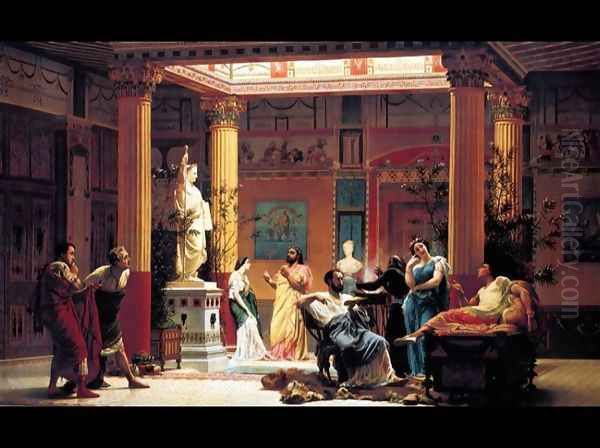

One of his most celebrated Neo-Grec works is A Rehearsal of "The Flute Player" and "The Wife of Diomedes" in the Atrium of the House of H.I.H. Prince Napoleon (1861), also known simply as The Flute Concert. This painting depicts a scene in the Pompeian-style villa of Prince Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoléon III's cousin) on the Avenue Montaigne in Paris. The villa itself was a famous example of Neo-Grec architecture, and Boulanger’s painting captures a private theatrical rehearsal within its meticulously recreated ancient Roman interiors. The work is a tour-de-force of archaeological detail, elegant figures, and sophisticated composition, perfectly embodying the Neo-Grec ideal of bringing antiquity to life in a relatable, almost domestic, manner. The painting was highly praised and further solidified Boulanger's reputation.

Another significant work in this vein is The Summer Repast at the House of Lucullus in Tusculum (1877), which imagines a luxurious banquet hosted by the famously epicurean Roman general Lucullus. Here, Boulanger revels in the depiction of classical opulence, with sumptuously dressed figures reclining in a lush garden setting, surrounded by fine food and drink. The painting showcases his mastery of color, texture, and complex group compositions.

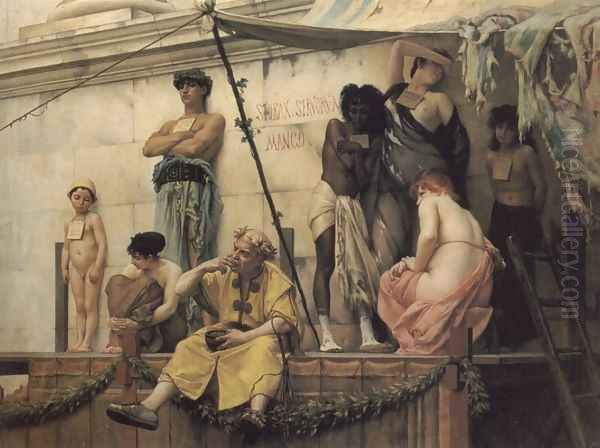

His historical paintings continued to be important. The Slave Market (1886), now in a private collection, is a powerful and somewhat unsettling Orientalist scene that, like Gérôme's similar subjects, combined ethnographic detail with a dramatic, and to modern eyes, problematic theme. He also contributed to large-scale decorative projects, a common undertaking for successful academic painters. Notably, he painted decorative panels for the Foyer de la Danse at the Palais Garnier, the new Paris Opera House, an immensely prestigious commission. He also created decorations for the town hall of the 13th arrondissement in Paris.

Academic Career and Pedagogical Influence

Beyond his own artistic production, Gustave Boulanger became a highly influential teacher. He was appointed a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, a position he held for many years. He also taught at the Académie Julian, a private art school that attracted a diverse, international student body, including many women and Americans who found the École des Beaux-Arts more difficult to access.

As a teacher, Boulanger was known for his rigorous adherence to academic principles. He emphasized the importance of strong drawing skills, a thorough understanding of anatomy, and the study of classical models. His pedagogical approach was traditional, focusing on building a solid technical foundation before allowing students to develop their individual styles. He, along with his colleague Jules Joseph Lefebvre, guided numerous aspiring artists.

Among his notable students were Henri Tenré, Henri-Lucien Doucet, and the American painter Charles Sprague Pearce. Through his teaching, Boulanger helped to perpetuate the academic tradition, instilling its values in a new generation of artists. While some of his students would later explore different artistic paths, the foundational training they received under Boulanger was often a crucial part of their development. The influence of Parisian ateliers like his extended far beyond France, as international students like Thomas Eakins and Kenyon Cox, who studied with Gérôme and other academicians, carried these methods back to their home countries.

Later Life, Honors, and Stance on Modern Art

Gustave Boulanger's career was crowned with official recognition. He was elected a member of the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts (part of the Institut de France) in 1882, succeeding William-Adolphe Bouguereau to one of its coveted chairs. This was one of the highest honors an artist could achieve in France, signifying his esteemed position within the artistic establishment. He was also made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1865, later promoted to Officer.

Throughout his later career, Boulanger remained a staunch defender of academic art. He was critical of the emerging avant-garde movements, particularly Impressionism, which challenged the very foundations of academic painting with its emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, subjective perception, and a looser, more visible brushwork. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro were revolutionizing the art world, and their approach was antithetical to Boulanger's carefully finished, meticulously detailed, and objectively rendered scenes.

Boulanger also expressed reservations about Naturalism, a movement that, while sharing academic art's commitment to realism, often focused on contemporary social issues and the unidealized depiction of rural or working-class life, as seen in the work of painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage. For Boulanger, art should aspire to beauty, timelessness, and the depiction of noble or historically significant themes, rather than the raw, sometimes harsh, realities of modern existence or the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere. His public statements and teaching reinforced these conservative artistic ideals, emphasizing the enduring value of tradition and the study of the Old Masters.

Personal Connections and Character

While much of Boulanger's public life revolved around his art and academic duties, some personal connections are known. He maintained a friendship with the literary giant Victor Hugo. This connection is interesting, as Hugo was a leading figure of the Romantic movement, which had an earlier, more emotionally charged aesthetic than Boulanger's typically classical or meticulously detailed style. However, the intellectual and artistic circles in Paris were often interconnected, and mutual respect could transcend stylistic differences. It's said that Hugo even composed poetry inspired by Boulanger, highlighting a shared appreciation for narrative and historical grandeur.

Boulanger was described by contemporaries as a dedicated and serious artist, deeply committed to his craft and the principles of academic art. His success was built on hard work, discipline, and an unwavering belief in the artistic values he espoused. His role as a teacher also suggests a desire to pass on his knowledge and uphold the standards he believed in.

Artistic Style in Retrospect

Gustave Boulanger's artistic style is a quintessential example of 19th-century French academicism, with particular strengths in the Neo-Grec and Orientalist genres. His work is characterized by:

1. Impeccable Draughtsmanship: Drawing was the cornerstone of academic training, and Boulanger was a master of line and form. His figures are anatomically correct and gracefully rendered.

2. Polished Finish: Like most academic painters, he favored a smooth, highly finished surface where brushstrokes were largely invisible, creating a sense of objective realism.

3. Historical and Archaeological Accuracy: Whether depicting ancient Rome or contemporary Algiers, Boulanger paid close attention to details of costume, architecture, and artifacts, lending an air of authenticity to his scenes. This was particularly evident in his Neo-Grec works, which often felt like carefully reconstructed historical tableaux.

4. Balanced Compositions: His paintings are carefully composed, often adhering to classical principles of balance, harmony, and clarity. Figures are arranged to lead the viewer's eye and enhance the narrative.

5. Rich Color and Light: While not as experimental as the Impressionists, Boulanger used color effectively to create mood and define form. His Orientalist works, in particular, often feature vibrant hues and a strong sense of light characteristic of North African settings.

6. Narrative Clarity: Boulanger's paintings usually tell a clear story, whether drawn from mythology, history, or contemporary exotic life. He excelled at capturing dramatic or poignant moments.

His style can be seen as a continuation of the classical tradition passed down from artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, with his emphasis on line and idealized form, and adapted by his own teachers like Delaroche. He shared with contemporaries like Gérôme, Bouguereau, and Alexandre Cabanel a commitment to high technical standards and the depiction of elevated or exotic subject matter.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Gustave Boulanger passed away in Paris in September 1888. At the time of his death, he was a highly respected and successful artist, a pillar of the French academic establishment. However, the tides of artistic taste were already turning. The Impressionists had held several independent exhibitions, and new avant-garde movements were on the horizon. In the decades that followed, academic art, including Boulanger's, fell dramatically out of favor, dismissed by modernist critics as staid, overly sentimental, or irrelevant.

For much of the 20th century, artists like Boulanger were largely relegated to the footnotes of art history, their works often languishing in museum storage. However, in recent decades, there has been a significant scholarly re-evaluation of 19th-century academic art. Art historians now recognize the technical brilliance, cultural significance, and distinct aesthetic achievements of these painters. Boulanger's work, with its blend of classical erudition, exotic allure, and meticulous craftsmanship, is increasingly appreciated for its own merits and as an important reflection of its time.

His contributions to the Neo-Grec movement helped to popularize a more accessible and charming vision of antiquity, while his Orientalist paintings contributed to a rich and complex genre that continues to fascinate and provoke discussion. As a teacher, he played a vital role in shaping a generation of artists, transmitting the rigorous discipline of the academic tradition. Gustave Boulanger may not have been a revolutionary, but he was a master of his chosen path, an artist who skillfully and beautifully captured the ideals and aspirations of his age. His paintings remain as testaments to a period of extraordinary artistic production and enduring aesthetic appeal.