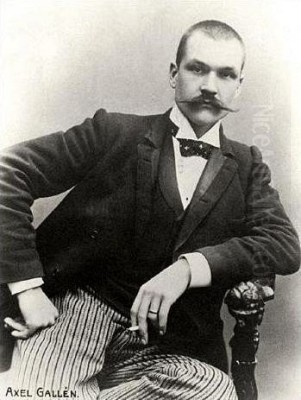

Akseli Gallen-Kallela stands as a monumental figure in Finnish art history, an artist whose work is inextricably linked with the forging of Finland's national identity. Born Axel Waldemar Gallén in 1865, he later adopted the more Finnish-sounding Gallen-Kallela, a change reflecting his deep commitment to his homeland's culture. Primarily celebrated for his powerful illustrations of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, Gallen-Kallela's artistic journey traversed Realism, Symbolism, National Romanticism, and even touched upon Expressionism, leaving behind a rich and diverse body of work that extended beyond painting into design and architecture. His life and art offer a compelling window into a nation awakening to its cultural heritage amidst the broader currents of European art at the turn of the 20th century.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Axel Waldemar Gallén was born on April 26, 1865, in Pori, a town on the west coast of Finland, which was then an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire. His family belonged to the Swedish-speaking upper class; his father, Peter Wilhelm Gallén, was a prominent figure, serving as both police chief and lawyer. His mother, Anna Mathilda (née Wahlroos), came from a wealthy Pori family. Despite this comfortable background, young Axel harbored a passion for painting from an early age, an ambition that met with stern disapproval from his father, who envisioned a more conventional, professional path for his son.

Yielding to paternal pressure, Axel was sent to Helsinki at the age of eleven to attend a grammar school. Formal education, however, did little to dampen his artistic inclinations. He secretly pursued drawing classes alongside his regular studies. A pivotal moment came in 1879 with the death of his father. Freed from this opposition, the fourteen-year-old Gallén could now fully dedicate himself to his true calling.

He enrolled in the drawing school of the Finnish Art Society in Helsinki, laying the foundational skills for his future career. Seeking more intensive training, he also took private lessons from Adolf von Becker, a respected Finnish painter and educator who ran his own academy. Von Becker, known for his academic approach combined with an awareness of contemporary French trends, provided Gallén with rigorous instruction in drawing and painting. It was during this period that Gallén began to develop his technical proficiency, initially working within the prevailing Realist mode.

His early works from the mid-1880s already showed considerable promise. One notable example is Old Woman with a Cat (1885). This painting, depicting a rustic interior scene with sensitivity and keen observation, is often cited as a pioneering work of Finnish Realism. It demonstrated Gallén's early ability to capture the character of ordinary Finnish life with honesty and empathy, moving away from the more idealized or romanticized depictions common earlier. This grounding in Realism would provide a solid base for his later stylistic explorations.

Parisian Years and Shifting Styles

Like many aspiring artists of his generation seeking exposure to the center of the art world, Gallén set his sights on Paris. In 1884, at the age of nineteen, he made the journey to the French capital. This move marked a crucial phase in his artistic development, exposing him to a vibrant milieu of international artists and avant-garde ideas that would profoundly shape his outlook and style.

He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school popular with foreign students, including many Scandinavians and Americans. There, he studied under renowned academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau. While the Académie Julian emphasized traditional academic training, focusing on drawing from life and mastering anatomy, the environment of Paris itself was electric with new artistic currents, from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism to the burgeoning Symbolist movement.

During his time in Paris, Gallén formed important friendships and connections. He became acquainted with fellow Finnish painter Albert Edelfelt, who was already established in Paris and served as a mentor figure to younger Finnish artists. He also encountered the provocative Swedish writer and artist August Strindberg, whose intense psychological dramas and interest in symbolism likely resonated with Gallén's evolving sensibilities. Another significant friendship was formed with the Norwegian painter Carl Dørager.

Exposure to the diverse art scene in Paris began to subtly shift Gallén's perspective. While he continued to refine his Realist technique, evident in works like Démasquée (1888), a sensitive study of a young woman, he also started absorbing other influences. The Symbolist movement, with its emphasis on suggestion, mood, and the exploration of inner worlds rather than objective reality, held a particular appeal. Artists were looking beyond surface appearances to convey deeper meanings, myths, and psychological states – ideas that would soon find fertile ground in Gallén's imagination, particularly in relation to his homeland's folklore.

His time in Paris was not continuous; he traveled back and forth between France and Finland. These journeys allowed him to contrast the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Paris with the landscapes and culture of his native land. This duality – the engagement with international trends and the deepening connection to Finnish roots – became a defining characteristic of his artistic identity. The Parisian experience equipped him with new tools and perspectives, but his subject matter increasingly turned towards Finland.

Return to Finland and National Romanticism

In 1890, Gallén made a significant personal commitment that coincided with his artistic reorientation towards Finnish themes. He married Mary Slöör, herself an aspiring artist from a culturally engaged family. Their union would be a lasting partnership, and they eventually had three children: Impi Marjatta, Kirsti, and Jorma. The stability of family life seemed to anchor his focus, and his artistic direction became increasingly centered on exploring and expressing Finnish culture.

This period saw Gallén immerse himself in the spirit of National Romanticism, a powerful cultural and artistic movement sweeping through Finland and other parts of Europe. In Finland, it was deeply connected to the growing desire for national self-determination under Russian rule. The movement sought inspiration in national folklore, history, and the unique character of the Finnish landscape. The Kalevala, the epic poem compiled by Elias Lönnrot from ancient Finnish oral tradition, became the cornerstone of this cultural awakening.

Gallén felt a profound connection to the Kalevala and the remote, wild region of Karelia in eastern Finland, considered the heartland of the epic's myths and legends. He undertook journeys to Karelia, sketching the landscapes and the people, seeking authentic inspiration for his art. This interest, sometimes termed Karelianism, was shared by other Finnish artists and writers of the time, including the composer Jean Sibelius, with whom Gallen-Kallela formed a close friendship.

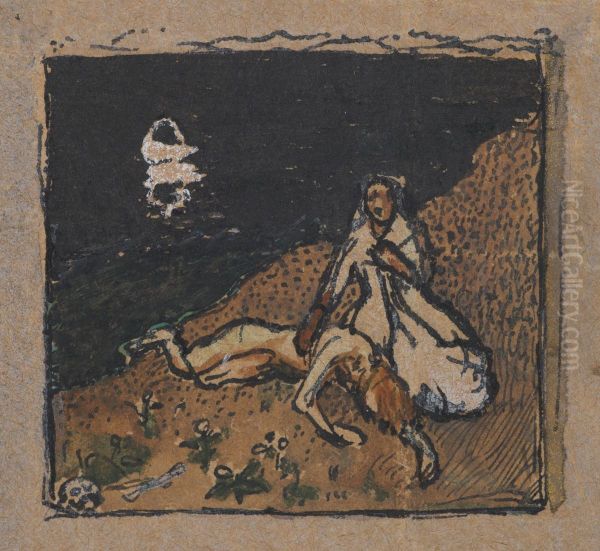

His artistic style began to decisively shift away from straightforward Realism towards a more monumental and symbolic approach suited to the epic themes he was tackling. One of the first major works signaling this change was the Aino Triptych (1891). Based on a tragic story from the Kalevala about the maiden Aino who drowns herself to escape marriage to the old sage Väinämöinen, the triptych combines realistic details in the depiction of figures and nature with a strong narrative and symbolic dimension. The work's decorative qualities and linear emphasis also hint at the influence of Art Nouveau, which was gaining traction across Europe. The Aino Triptych was a landmark achievement, establishing Gallén as a leading interpreter of the national epic.

The Kalevala Cycle: Defining an Epic

While the Aino Triptych marked a significant step, it was Gallén's subsequent, sustained engagement with the Kalevala throughout the 1890s and early 1900s that truly cemented his reputation and produced his most iconic works. He envisioned a grand series of paintings and illustrations that would bring the national epic to life for the Finnish people, becoming visual touchstones for their shared cultural heritage.

His approach was ambitious and innovative. He sought not merely to illustrate the text but to capture the primal power, the mythical atmosphere, and the psychological depth of the Kalevala's stories. His style evolved further, incorporating elements of Symbolism, Synthetism (influenced perhaps by artists like Paul Gauguin, emphasizing flat color areas and strong outlines), and even the decorative linearity of Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), which were highly influential in European art circles at the time.

Among the most celebrated works from this period is The Defense of the Sampo (1896). This dynamic composition depicts a dramatic scene from the Kalevala where the heroes Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen, and Lemminkäinen battle the evil witch Louhi for possession of the Sampo, a magical artifact that brings prosperity. The painting is characterized by its bold composition, stylized figures, strong colors, and energetic lines, conveying the intensity of the mythical struggle. It exemplifies Gallén's mature Kalevala style, blending national themes with modern artistic sensibilities.

Another powerful work is Lemminkäinen's Mother (1897). This poignant painting illustrates the moment when Lemminkäinen's mother retrieves the dismembered body of her son from the river of Tuonela, the land of the dead, and attempts to piece him back together. The composition is stark and emotionally charged, rendered with a somber palette and simplified forms that enhance the scene's mythical and symbolic weight. The figure of the grieving yet determined mother became an emblem of maternal love and resilience.

Kullervo's Curse (1899) tackles one of the most tragic tales in the Kalevala, that of the ill-fated hero Kullervo. Depicted with raw emotion against a dramatic, stylized landscape, Kullervo is shown cursing the god Ukko after realizing he has unwittingly seduced his own sister. The painting's expressive intensity borders on Expressionism, showcasing Gallén's ability to convey powerful psychological states through visual means.

These Kalevala paintings, along with numerous illustrations and sketches, were widely reproduced and became immensely popular in Finland. They played a crucial role in visualizing the national epic and fostering a sense of shared cultural identity during a period of political uncertainty. Gallén's interpretations became so influential that for many Finns, his images are synonymous with the Kalevala itself. His achievement lies in creating a visual language that felt both authentically Finnish and artistically modern.

Master of Multiple Disciplines: Design and Architecture

Akseli Gallen-Kallela's creative energy was not confined to painting and illustration. He was a true polymath of the arts, actively engaging in design, applied arts, and architecture, embodying the Art Nouveau ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) where artistic principles permeate all aspects of life and environment. His work in these fields further contributed to the development of a distinct Finnish national style.

A major platform for showcasing his diverse talents came with the Paris Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) of 1900. Finland, seeking to assert its cultural autonomy within the Russian Empire, had its own pavilion designed by the architectural trio Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren, and Eliel Saarinen. Gallen-Kallela was commissioned to create frescoes for the pavilion's central dome. Drawing themes from the Kalevala, including scenes related to the forging of the Sampo and Finland's natural resources, these frescoes were a triumph. Executed in a bold, graphic style, they captivated international audiences and won Gallen-Kallela several gold medals, significantly boosting his international reputation and highlighting Finnish culture on a world stage.

His interest in applied arts led him to collaborate with his friend, the Swedish-born artist and designer Louis Sparre, who founded the Iris Company in Porvoo, Finland. This workshop aimed to produce high-quality furniture, ceramics, and textiles based on Finnish traditions combined with modern design principles, very much in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau. Gallen-Kallela designed furniture and, notably, textiles, including modern interpretations of the traditional Finnish ryijy rug. His design Liekki (Flame), created around 1900, is often considered a seminal work of modern Finnish textile design, characterized by its bold, abstract pattern and vibrant colors.

Gallen-Kallela also turned his hand to architecture, most famously in the design of his own wilderness studio home, named "Kalela," built between 1894 and 1895 on the shore of Lake Ruovesi. Constructed in the National Romantic style using traditional log building techniques, Kalela was conceived as an integrated artistic environment. He designed not only the building but also much of its interior furnishings and details. Kalela became his sanctuary, a place for focused work away from the distractions of the city, and a gathering place for fellow artists and cultural figures, including Jean Sibelius and the sculptor Emil Wikström. Today, Kalela serves as one part of the Gallen-Kallela Museum, preserving his legacy.

Through his work in frescoes, textiles, furniture, and architecture, Gallen-Kallela demonstrated a holistic artistic vision. He believed that art should not be confined to galleries but should enrich everyday life, and that a truly national style could be expressed across multiple mediums, drawing inspiration from Finland's unique heritage and natural environment.

Mature Style and Later Explorations

Entering the 20th century, Gallen-Kallela continued to evolve as an artist, exploring new themes and refining his style, while remaining deeply connected to Finnish identity. In 1907, he formally changed his name from the Swedish Axel Gallén to the more Finnish Akseli Gallen-Kallela, a public declaration of his cultural allegiance.

His landscape painting continued alongside his epic themes. The series of paintings depicting Lake Keitele (primarily around 1905) are among his most admired landscapes. These works capture the shimmering light on the water and the distinctive atmosphere of the Finnish lake district. While rooted in observation, they possess a rhythmic quality and a subtle stylization, particularly in the treatment of the water's surface, which some critics have linked to the influence of Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Gauguin or even Japanese prints. They convey a sense of tranquility and a deep, almost spiritual connection to the Finnish nature.

A significant departure, showcasing his engagement with more contemporary European trends, is the Portrait of Maxim Gorky (1906). Gallen-Kallela painted the Russian writer during Gorky's brief exile in Finland. The portrait is rendered with an expressive intensity, using bold brushwork and a somewhat stark lighting that captures the writer's brooding presence. The style leans towards Expressionism, emphasizing psychological insight over photographic likeness, and stands as a powerful example of Gallen-Kallela's portraiture.

His involvement in national affairs continued. During the Finnish Civil War of 1918, which followed Finland's declaration of independence, Gallen-Kallela sided with the conservative "White" faction. He even served briefly as adjutant to the Regent of Finland, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, and designed uniforms and medals for the newly independent nation. This period reflects his strong patriotic convictions, though his direct political involvement was relatively short-lived.

His artistic explorations also took him further afield. He had long been fascinated by other cultures, and this interest culminated in a significant journey.

Journeys and Final Years

In the later part of his career, Gallen-Kallela's wanderlust took him far beyond Europe. Between 1909 and 1911, he undertook a major trip to British East Africa (present-day Kenya) with his family. This journey marked a distinct phase in his work, as he turned his attention from Finnish mythology to the landscapes, wildlife, and people of Africa.

He spent considerable time painting and sketching, captivated by the intense light, vibrant colors, and exotic fauna. Despite challenging conditions, including illness, he produced a substantial body of work, including landscapes, animal studies, and portraits of local people. These African works often display a brighter palette and a looser, more expressive brushwork compared to his Finnish paintings. They reflect his fascination with the 'primitive' and the exotic, themes common among European artists at the time, but also demonstrate his continued skill as an observer and his adaptability to new environments and subjects. Works like Indian Chief Kérlûk (1923, likely based on earlier sketches or later travels) show this continued interest.

Following his African sojourn, Gallen-Kallela's travels continued. In the 1920s, he spent several years in the United States, primarily in Taos, New Mexico, which had become an artists' colony attracting figures interested in Native American culture and the dramatic southwestern landscape. Here, he studied Pueblo Indian art and culture, finding parallels perhaps with the ancient traditions of his own homeland. He painted landscapes and portraits, absorbing the unique atmosphere of the American Southwest.

He returned to Finland in 1926. His final major project involved returning to the Kalevala. He began work on illustrations for a planned "Great Kalevala," revisiting his most cherished theme with the benefit of decades of artistic experience. He also undertook the task of painting frescoes based on his earlier Paris Expo designs for the ceiling of the entrance hall of the National Museum of Finland in Helsinki, completing them in 1928.

Tragically, his life was cut short. While returning from a lecture in Copenhagen in March 1931, Akseli Gallen-Kallela contracted pneumonia and died in Stockholm on March 7, at the age of 65. He left behind an immense artistic legacy, deeply rooted in Finland but recognized internationally.

Artistic Style and Influences (Summary)

Akseli Gallen-Kallela's artistic journey was one of dynamic evolution, absorbing diverse influences while forging a unique and powerful style deeply connected to his Finnish identity. His development can be broadly traced through several key phases and influences:

Initially grounded in Realism, particularly the plein-air naturalism prevalent in the 1880s, his early works focused on accurate depictions of Finnish rural life and landscapes. Teachers like Adolf von Becker provided a solid academic foundation, while exposure to French Realism during his early Paris visits refined his technique.

The 1890s marked a decisive shift towards Symbolism and National Romanticism. Inspired by the Kalevala and the burgeoning Finnish national consciousness, he moved beyond mere representation to explore myth, legend, and psychological depth. European Symbolist currents, possibly encountered through artists and writers like August Strindberg, provided a framework for expressing these inner worlds. His Kalevala works from this period often incorporate elements of Synthetism, using simplified forms, strong outlines, and flat areas of color, reminiscent of Paul Gauguin or the Pont-Aven school.

The influence of Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) is also evident in the decorative qualities, flattened perspectives, and bold linearity found in works like The Defense of the Sampo. This Japonisme was a common feature of European art at the time, but Gallen-Kallela integrated it effectively into his national themes.

His engagement with the Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) movement is clear in his design work – the frescoes for the Paris Pavilion, the Iris Company textiles like Liekki, and the integrated design of his Kalela studio. The emphasis on organic forms, decorative patterns, and the unification of art and craft aligns perfectly with Art Nouveau principles.

In the early 20th century, elements of Expressionism emerged in his work, particularly in portraiture like the Maxim Gorky painting and later in some of his African works. This involved a greater emphasis on subjective emotion, expressive brushwork, and sometimes distorted forms to convey psychological intensity or the raw energy of his subject.

Throughout his career, Gallen-Kallela maintained a connection to landscape painting, where influences from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism can be seen in his treatment of light and color, as in the Lake Keitele series. He remained a versatile artist, comfortable working across different styles and mediums, always adapting his approach to suit the subject matter, whether it was the epic grandeur of the Kalevala, the intimate character of a portrait, or the shimmering light on a Finnish lake.

Contemporaries and Connections

Gallen-Kallela did not work in isolation. His career intersected with numerous significant figures in Finnish and European art and culture. His teachers, Adolf von Becker in Helsinki and William-Adolphe Bouguereau in Paris, represented the academic tradition against which he partly reacted but from which he also gained essential skills. Von Becker's students also included notable Finnish artists like Pekka Halonen and Torsten Wasastjerna.

In Paris, his friendships with fellow Finn Albert Edelfelt, the Swede August Strindberg, and the Norwegian Carl Dørager placed him within a vibrant circle of Nordic artists abroad. His association with Louis Sparre was crucial for his involvement in the applied arts through the Iris Company.

Within Finland, his most significant artistic friendship was arguably with the composer Jean Sibelius. They shared a deep commitment to Finnish culture and the Kalevala, and their circle, sometimes referred to as the "Symposium" group, was central to the National Romantic movement. He also knew fellow sculptor Emil Wikström. While Elias Lönnrot, the compiler of the Kalevala, belonged to an earlier generation, his work was the foundational inspiration for much of Gallen-Kallela's output.

His style shows awareness of international trends associated with figures like Paul Gauguin (Synthetism, 'primitive' themes) and potentially Henri Matisse, who also studied briefly at the Académie Julian, though their paths may not have directly crossed significantly there. His portrait subject, Maxim Gorky, connects him to the turbulent world of Russian literature and politics. Gallen-Kallela's ability to engage with these diverse figures and movements while maintaining his distinct artistic voice is a testament to his stature.

Legacy

Akseli Gallen-Kallela's legacy is profound and enduring, particularly within Finland. He is widely regarded as one of the country's most important artists, a key figure in the "Golden Age" of Finnish art around the turn of the 20th century. His Kalevala illustrations are not merely artworks; they are deeply embedded in the Finnish national psyche, shaping how generations have visualized their foundational epic.

His contribution to National Romanticism was immense, providing powerful visual symbols that helped define and strengthen Finnish cultural identity during a crucial period of political aspiration. He successfully synthesized international artistic trends – Realism, Symbolism, Art Nouveau – with uniquely Finnish themes and sensibilities, creating a style that was both modern and deeply rooted in national heritage.

Beyond his Kalevala works, his achievements in landscape painting, portraiture, and especially in the applied arts and design, demonstrate his remarkable versatility. He helped elevate the status of Finnish design and craft, promoting the idea of a unified artistic environment. His wilderness studio, Kalela, now part of the Gallen-Kallela Museum (along with his later home and studio in Tarvaspää, Espoo), stands as a monument to his life and work, preserving his artistic environment for future generations.

While deeply Finnish, Gallen-Kallela also achieved significant international recognition during his lifetime, particularly through his success at the 1900 Paris Exposition. His work continues to be studied and exhibited internationally, appreciated for its artistic power, its unique blend of influences, and its compelling connection to the myths and landscapes of Finland. He remains a pivotal figure, the painter who gave visual form to the soul of a nation.