Alvar Cawén stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Finnish art. A pivotal member of the November Group, his work is characterized by a profound emotional depth, a distinctive use of color, and an engagement with the modernist currents sweeping across Europe. His journey from the rural heartlands of Finland to the bustling art scenes of Paris and beyond shaped a unique artistic voice that contributed significantly to the development of Finnish modernism. This exploration delves into the life, influences, artistic style, key works, and lasting legacy of Alvar Cawén, an artist who skillfully blended international trends with a deeply personal and national sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

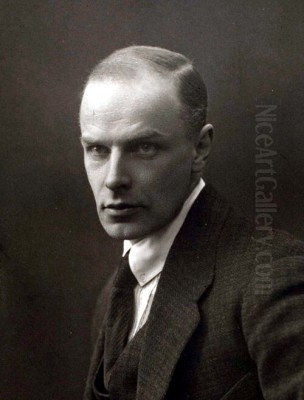

Born on June 8, 1886, in Korpilahti, a rural municipality in Central Finland, Alvar Cawén's early life was steeped in an environment that, while perhaps not overtly artistic in a metropolitan sense, provided a foundational connection to the Finnish landscape and character. His father was a clergyman, Revd. F. A. Cawén, suggesting a childhood within a family of certain standing and intellectual pursuit. This upbringing likely instilled in him a reflective nature, a quality often discernible in the introspective mood of his later works.

The turn of the century was a period of burgeoning national consciousness in Finland, then an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire. This cultural ferment, which saw artists and intellectuals seeking to define a distinct Finnish identity, would undoubtedly have formed part of the backdrop to Cawén's formative years. It was in this atmosphere that his artistic inclinations began to take root. His family, including his future wife Eleanora Boije, whom he would later marry, shared a keen interest in both music and the visual arts, creating a supportive milieu for a young man drawn to creative expression. This familial appreciation for culture likely played a crucial role in encouraging his decision to pursue art professionally.

Formative Years: Helsinki and Paris

Cawén's formal artistic training began in Helsinki, the vibrant capital that was rapidly becoming the center of Finland's artistic life. From 1905 to 1907, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts (Suomen Taideyhdistyksen piirustuskoulu, now part of the University of the Arts Helsinki). This institution was instrumental in training a generation of Finnish artists, providing them with the technical skills and theoretical grounding necessary to embark on their careers. Here, Cawén would have been exposed to the prevailing academic traditions, but also to the newer artistic ideas beginning to filter into Finland from continental Europe. Teachers like Albert Gebhard and Eero Järnefelt were influential figures in the Finnish art scene, though their styles were more rooted in Realism and National Romanticism.

However, like many ambitious young artists of his time, Cawén recognized that Paris was the undisputed epicenter of the avant-garde. In 1908, he made the journey to the French capital, a move that would prove transformative for his artistic development. He enrolled to study under Lucien Simon from 1908 to 1909. Simon, along with artists like Charles Cottet and René Ménard, was part of a group sometimes referred to as the "Bande Noire" or "Nubians" due to their often somber palettes and depictions of peasant life, particularly in Brittany. While not radical modernists themselves, their emphasis on expressive realism and atmospheric painting provided a solid, if somewhat traditional, counterpoint to the more revolutionary movements brewing in Paris.

During his time in Paris, Cawén would have inevitably encountered the seismic shifts occurring in the art world. Fauvism, with its explosive use of color championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, was making waves. More significantly, the early stirrings of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, were beginning to deconstruct traditional notions of form and space. While Cawén did not immediately adopt these radical styles, the intellectual ferment and visual experimentation of Paris undoubtedly broadened his artistic horizons and planted seeds that would germinate in his later work. He returned to Finland and held his first exhibition in 1910, marking his official debut as a professional artist. He would revisit Paris in 1912, further immersing himself in its dynamic art scene before returning to Finland the following year.

The November Group: A Collective Voice for Finnish Modernism

The period leading up to and during the First World War was a time of intense artistic activity and re-evaluation in Finland. In this climate, new artistic groupings emerged, seeking to break away from established norms and forge a distinctly modern Finnish art. One of the most important of these was the November Group (Marraskuun ryhmä), of which Alvar Cawén became a founding member in late 1916.

The November Group, spearheaded by the charismatic and often controversial Tyko Sallinen, was a loose association of artists united by their commitment to Expressionism and, to varying degrees, an interest in Cubist principles. Other key members included Marcus Collin, Juho Mäkelä, Gabriel Engberg, Mikko Oinonen, and the sculptor Wäinö Aaltonen. These artists shared a desire to move beyond the romanticized national landscapes and academic portraiture that had characterized much of Finnish art. Instead, they sought a more direct, emotionally charged, and formally innovative means of expression.

Their work was often characterized by strong, sometimes somber colors, bold brushwork, a simplification or distortion of forms, and a focus on subjective experience. There was a raw, unvarnished quality to much of their art, which sometimes shocked contemporary audiences accustomed to more polished and idealized representations. The November Group's art also carried strong nationalistic undercurrents, not in a sentimental or folkloric way, but in its attempt to capture what they perceived as the authentic, rugged character of Finland and its people. This was particularly poignant as Finland moved towards independence, which it declared in 1917.

Cawén's involvement with the November Group was crucial for his development. It provided him with a supportive network of like-minded artists and a platform for exhibiting his increasingly modernist works. His style during this period solidified, embracing the expressive potential of color and form, and often imbued with a melancholic or introspective mood that became a hallmark of his oeuvre. The group's collective impact was significant, pushing Finnish art decisively into the modern era and challenging the conservative tastes of the art establishment.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Alvar Cawén's artistic style is primarily identified with Expressionism, though it also incorporates discernible influences from Cubism and Post-Impressionism. His approach was not one of rigid adherence to any single doctrine but rather a personal synthesis of various modernist tendencies, all filtered through his unique sensibility.

A key characteristic of Cawén's Expressionism is its emotional intensity. He sought to convey inner states and subjective experiences rather than merely replicating external appearances. This is evident in his portraits, which often possess a psychological depth and a sense of quiet introspection. His figures are not idealized; instead, they convey a sense of human vulnerability and contemplation. His use of color was central to this expressive aim. While sometimes employing a darker, more somber palette, particularly in his earlier works – perhaps reflecting the influence of artists like Lucien Simon or the general Nordic penchant for melancholic tones seen in figures like Edvard Munch – Cawén could also utilize richer, more vibrant hues to heighten emotional impact. His brushwork was often visible and energetic, contributing to the overall expressive force of his paintings.

The influence of Cubism is most apparent in Cawén's treatment of form and space. He often simplified objects into geometric shapes and faceted planes, suggesting multiple viewpoints simultaneously. However, unlike the more analytical Cubism of Picasso or Braque, Cawén's engagement with Cubist principles was always subservient to his expressive goals. He used its formal language to structure his compositions and enhance their emotional resonance, rather than as an end in itself. This integration of Cubist elements within an Expressionist framework was a common feature among many artists of the November Group.

Cawén's thematic concerns were varied. Landscapes, particularly those depicting the Finnish countryside, were a recurring subject. These were not picturesque renderings but rather interpretations imbued with mood and atmosphere, often reflecting a deep connection to his native land. He also painted still lifes and interior scenes. A particularly notable series of works is "The Atelier," which depicts artists in their studios or scenes related to the creation of art. These paintings offer a glimpse into the artist's world and perhaps a meta-commentary on the artistic process itself.

Another interesting and somewhat unique aspect of his subject matter was his depiction of dogs, specifically Finnish breeds like the Stövare (Finnish Hound) and Spitz. These were not mere animal portraits but often carried symbolic weight, reflecting national identity and perhaps a sense of hope or resilience, particularly in the context of Finland's struggle for and achievement of independence. These works resonated with a public that saw these native breeds as emblematic of Finnish character.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Alvar Cawén's oeuvre, illustrating the evolution of his style and his thematic preoccupations.

"River Landscape" (1916): This painting, created during the formative period of the November Group, showcases Cawén's early modernist tendencies. While still rooted in landscape, the treatment of form and color likely shows a departure from purely naturalistic representation. The work's donation to the Finnish National Gallery (Ateneum) by Arvid Sourander indicates its perceived importance even relatively early in his career. It would reflect his engagement with capturing the essence of the Finnish environment through an expressive lens.

"The Atelier" (Series, various dates): This series is significant for its focus on the artist's creative space and process. These paintings often feature figures absorbed in their work, surrounded by the tools and products of their art. The compositions might employ Cubist-influenced spatial arrangements and an Expressionist rendering of figures and atmosphere. They offer insights into Cawén's reflections on art itself and the life of an artist, a theme explored by many modern painters from Gustave Courbet to Henri Matisse.

"The Convalescent" (1923): Housed in the Finnish National Gallery, this painting is a powerful example of Cawén's mature Expressionist style. The subject, a figure recovering from illness, lends itself to an exploration of vulnerability, introspection, and the fragility of the human condition. Cawén's handling of form, color, and light would be employed to convey the emotional and psychological state of the convalescent. The palette might be subdued or subtly modulated to enhance the mood of quiet contemplation or weariness. Such works highlight his ability to imbue intimate human scenes with profound emotional resonance.

Paintings of Finnish Dogs (various dates): As mentioned, Cawén's depictions of Finnish dog breeds like the Stövare and Spitz were popular and symbolically charged. These works often went beyond simple animal portraiture, using the dogs as symbols of Finnish identity, loyalty, and resilience. In the context of a newly independent nation forging its cultural symbols, these paintings struck a chord. His ability to capture the characteristic forms and spirit of these animals, combined with his expressive style, made these works distinctive.

These examples, among many others, demonstrate Cawén's versatility and the consistent emotional depth of his work. His paintings are not merely formal exercises but are imbued with a sense of lived experience and a deep engagement with his subjects, whether they be landscapes, human figures, or symbolic animals. His main body of work is fittingly housed in the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki, the premier repository of Finnish national art.

Travels, Teaching, and Continued Development

The period following the First World War saw Cawén continue to develop as an artist and expand his horizons. In 1919, with Europe slowly recovering from the conflict, he embarked on a significant journey, traveling to Denmark, Italy, Spain, and France. Such travels were vital for artists, offering opportunities to see historical masterpieces firsthand, experience different cultures, and engage with contemporary artistic developments in other countries. This exposure would have further enriched his artistic vocabulary and perspective.

During this period abroad, Cawén also took on teaching roles, serving as a painting instructor in Denmark, Italy, and Spain. This experience of teaching would have required him to articulate his own artistic principles and engage critically with the work of others, a process that often clarifies and deepens an artist's own understanding.

He returned to Finland in 1921 and continued his involvement in art education. He was appointed a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, the very institution where he had begun his studies. He held this position until 1922. His role as an educator allowed him to influence a new generation of Finnish artists, passing on the modernist principles he had embraced and developed.

Even after settling back in Finland, Cawén continued to travel. He made further trips to France, Italy, and Belgium, and revisited Finland in 1929, suggesting a continued desire to remain connected with the broader European art world while maintaining his roots in his homeland. These journeys ensured that his art did not become insular but remained in dialogue with international currents. His experiences abroad, combined with his deep understanding of Finnish culture and landscape, contributed to the distinctive character of his work, which managed to be both modern and deeply Finnish.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

Alvar Cawén continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1920s and into the early 1930s. His style, while established, likely continued to evolve subtly as he responded to new experiences and artistic ideas. He remained a respected figure in the Finnish art world, recognized for his contribution to the breakthrough of modernism in the country.

His personal life, particularly his marriage to Eleanora Cawén (née Boije), who shared his passion for art and music, provided a stable and culturally rich environment. Their home was reportedly a gathering place for many artist friends, fostering a lively exchange of ideas. This supportive personal context was undoubtedly important for his creative endeavors.

Alvar Cawén passed away on March 3, 1935, at the relatively young age of 48. Despite a career that spanned roughly two and a half decades, his impact on Finnish art was substantial. He was a key figure in a generation of artists who fundamentally reshaped the Finnish art scene, moving it away from 19th-century academicism and National Romanticism towards a modern, internationally aware, yet distinctly Finnish form of expression.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a founding member of the November Group, he played a crucial role in establishing Expressionism as a major force in Finnish art. His willingness to incorporate elements of Cubism demonstrated an openness to international avant-garde movements. Artists like Tyko Sallinen, Marcus Collin, and Cawén himself were instrumental in this shift, facing initial resistance but ultimately paving the way for subsequent generations.

Cawén's work is celebrated for its emotional depth, its skillful use of color and form to convey subjective experience, and its ability to capture a certain Finnish sensibility – often characterized by a blend of melancholy, resilience, and a deep connection to nature. His paintings are not merely historical artifacts; they continue to resonate with viewers today due to their humanism and artistic integrity.

He stands alongside other important Nordic modernists who sought to forge a path that was both contemporary and rooted in their specific cultural contexts. While perhaps not as internationally renowned as Edvard Munch from Norway, or some of the German Expressionists like Emil Nolde or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Cawén's contribution to his national art scene is undeniable. He helped to define what modern Finnish art could be, influencing peers and younger artists alike. His works remain a testament to a pivotal period in Finnish cultural history and a significant chapter in the broader story of European modernism. His paintings in the Ateneum and other collections ensure that his unique artistic voice continues to be heard and appreciated.

Cawén in the Context of European Art

Alvar Cawén's artistic journey unfolded during one of the most dynamic and revolutionary periods in European art history. To fully appreciate his contributions, it is useful to place him within this broader context. When Cawén first arrived in Paris in 1908, the city was a crucible of innovation. The legacy of Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin was being actively reinterpreted. Cézanne's structural approach to composition was a key inspiration for the nascent Cubist movement, while Van Gogh's expressive use of color and Gauguin's Symbolist tendencies resonated with artists seeking more subjective forms of expression.

The Fauvist explosion of color, led by Matisse and Derain around 1905, had already challenged traditional notions of representation. Simultaneously, in Germany, groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge), formed in Dresden in 1905 by artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Erich Heckel, were pioneering a raw, emotionally charged form of Expressionism. Later, Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group in Munich, including Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, would explore more spiritual and abstract dimensions of Expressionism.

Cawén's development reflects an engagement with these currents, particularly Expressionism and Cubism. His adoption of expressive distortion and heightened color aligns him with the broader Expressionist movement that swept across Northern and Central Europe. Like his German counterparts, Cawén sought to convey inner emotional realities rather than objective visual facts. However, Finnish Expressionism, as exemplified by the November Group, often had a distinct character – perhaps less overtly angst-ridden than some German Expressionism, and more connected to the national landscape and identity, sometimes with a rugged, earthy quality.

His incorporation of Cubist elements – the faceting of forms, the simplification of objects into geometric planes – shows his awareness of the formal innovations emanating from Paris. However, unlike the more analytical or synthetic Cubism of Picasso, Braque, or Juan Gris, Cawén, like many other artists outside the movement's core, adapted Cubist devices to serve his pre-existing expressive aims. This "Cubist-Expressionist" synthesis was a common phenomenon across Europe, as artists selectively borrowed from different avant-garde styles to forge their own idioms. One might see parallels in the work of French artists like André Lhote, who sought to reconcile Cubism with a more traditional sense of order, or even in some aspects of Italian Futurism, which also drew on Cubist fragmentation.

Cawén's travels and teaching experiences further underscore his connection to the wider European art world. His time spent in Italy and Spain would have exposed him not only to the great art of the past but also to contemporary movements in those countries. While Finland might have been geographically on the periphery of Europe, artists like Cawén ensured it was not culturally isolated. He, along with contemporaries such as Helene Schjerfbeck (though of an older generation and with a very different, refined modernist style), Magnus Enckell, and Verner Thomé, played a vital role in mediating between international trends and the specificities of the Finnish cultural context. They were part of a network of Nordic artists who often studied in Paris or Germany and brought back new ideas, adapting them to their own artistic visions and national traditions, much like Akseli Gallen-Kallela had done for National Romanticism a generation earlier.

Conclusion

Alvar Cawén remains a compelling and important figure in the history of Finnish art. As an artist, he navigated the complex currents of early 20th-century modernism with skill and sensitivity, forging a distinctive style that blended the emotional intensity of Expressionism with the formal innovations of Cubism. His work is characterized by its psychological depth, its often somber yet rich color palette, and its profound connection to Finnish identity and landscape.

As a founding member of the November Group, he was at the forefront of a movement that decisively shifted Finnish art towards modernity, challenging established conventions and paving the way for future generations. His contributions as an educator further solidified his influence. Through his paintings of introspective portraits, evocative landscapes, symbolic animal depictions, and scenes from the artist's studio, Cawén explored themes of human emotion, national character, and the very nature of artistic creation. His legacy endures in his artworks, which continue to offer a powerful and moving vision of a pivotal era in Finnish and European art. Alvar Cawén's dedication to his craft and his unique artistic voice ensure his place as a significant master of Finnish modernism.