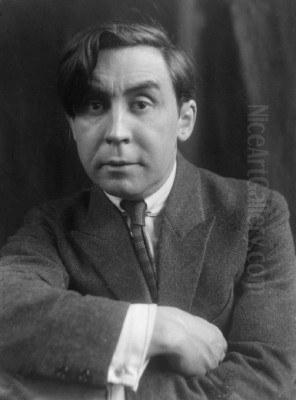

Albert Gleizes stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of modern art, particularly renowned as a co-founder and principal theorist of Cubism. His life (1881-1953) spanned a period of radical artistic transformation, and his contributions extended beyond painting into writing, philosophy, and the creation of artistic communities. A French national, Gleizes navigated the complex currents of early 20th-century art, leaving an indelible mark not only through his canvases but also through his influential texts and enduring commitment to integrating art with life and spirituality. His journey from Impressionist-influenced beginnings to pioneering Cubism and later developing a unique form of abstraction reflects a relentless intellectual and artistic quest.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris on December 8, 1881, Albert Léon Gleizes grew up in an environment connected to the applied arts. His father ran a workshop specializing in decorative fabric design, an experience that likely provided an early exposure to pattern, structure, and industrial application, elements that would subtly inform his later work. Rather than pursuing formal academic art training immediately, Gleizes initially worked in his father's studio after completing his secondary education. Around the age of 19, however, his passion for painting solidified.

Between 1901 and 1905, Gleizes balanced his work obligations with learning to paint and fulfilling his mandatory military service. This period was crucial for his self-directed artistic education. He began painting landscapes and scenes of daily life, initially absorbing the influences of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. His early works demonstrate a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, typical of the Impressionist painters like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, but soon showed a growing interest in structure and simplified forms, hinting at the direction his art would take.

In 1902, Gleizes achieved his first public recognition when his painting, La Seine à Asnières (The Seine at Asnières), was exhibited at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. This work, while still reflecting an Impressionist sensibility, marked his official entry into the Parisian art world. He continued to exhibit in subsequent years, gradually moving away from purely observational painting towards compositions with greater emphasis on design and social commentary, reflecting an engagement with the world around him.

During these formative years, Gleizes also demonstrated a commitment to social ideals. In 1905, he was involved in founding the Association Ernest-Renan, a group dedicated to providing education for the working class, aiming to bridge the gap between intellectual pursuits and manual labor, and challenge bourgeois cultural norms. This early engagement with social philosophy foreshadowed his later efforts to create utopian artistic communities.

The Abbaye de Créteil: An Artistic and Social Experiment

Gleizes's interest in community and alternative ways of living and creating art led him, in 1906, to co-found the Abbaye de Créteil. Located in a large house in Créteil, a suburb southeast of Paris, this venture was established with a group of like-minded writers and artists, including the poet René Arcos, Henri-Martin Barzun, and Alexandre Mercereau. It was conceived as a phalanstery, a self-supporting utopian community inspired by Fourierist ideals, where artists and writers could live and work collaboratively, free from the constraints of the commercial art market and bourgeois society.

The Abbaye aimed to foster an art that reflected modern life and collective experience, moving beyond traditional narrative and descriptive modes. The members engaged in various activities, including painting, poetry, publishing, and even printing their own works. Gleizes was central to the artistic direction, exploring themes of modern life, labor, and landscape through an increasingly structured and simplified style. The Abbaye provided a fertile ground for intellectual exchange and artistic experimentation, attracting visitors and fostering connections within the burgeoning avant-garde.

Despite its ambitious goals and creative energy, the Abbaye de Créteil faced significant financial difficulties. The communal experiment proved unsustainable in the long run, and the group was forced to disband in early 1908. However, the experience profoundly shaped Gleizes's worldview and reinforced his belief in the social role of the artist and the importance of collective artistic endeavor. The connections forged there would also prove important as he moved into the next phase of his career.

Embracing Cubism: A New Vision

Around 1909 and 1910, Gleizes's artistic path intersected decisively with the nascent Cubist movement. He became acquainted with artists who were similarly exploring new ways of representing reality, breaking from traditional perspective and representation. Key figures he connected with during this time included Jean Metzinger, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, and Fernand Léger. These artists, often exhibiting together at the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne, formed the core of what would become known as the "Salon Cubists."

Gleizes's work rapidly evolved under these new influences. He abandoned the lingering Impressionist elements and fully embraced the geometric fragmentation, multiple viewpoints, and dynamic compositions characteristic of early Cubism. His paintings from this period, such as Femme aux Phlox (Woman with Phlox, 1910), demonstrate this transition, showing figures and objects broken down into faceted planes, yet retaining a sense of volume and structure within a complex, integrated pictorial space.

The public debut of Cubism as a coherent movement largely occurred through the Salon exhibitions. In 1910, Gleizes, Metzinger, Delaunay, and Le Fauconnier exhibited together at the Salon d'Automne, causing a stir among critics and the public. The following year, at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, these artists, along with others like Marie Laurencin and Roger de La Fresnaye, exhibited together in Room 41 ("Salle 41"), an event often cited as the first major group manifestation of Cubism. Gleizes's monumental painting La Chasse (The Hunt) was a prominent feature.

Unlike the more intimate, analytical Cubism being developed concurrently by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the seclusion of their studios and promoted by the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the Salon Cubists presented large-scale works depicting modern life, landscapes, and group scenes. Their approach was often more colorful and dynamic, incorporating ideas about simultaneity and collective experience that resonated with Gleizes's earlier interests.

Du "Cubisme": Theorizing the Movement

As Cubism gained momentum and visibility, the need for a theoretical framework became apparent. Albert Gleizes, alongside his close collaborator Jean Metzinger, took on this crucial task. Together, they authored Du "Cubisme" (On Cubism), published in late 1912 by Eugène Figuière. This book was the first major theoretical treatise on the movement and proved immensely influential, quickly being translated into English and Russian.

Du "Cubisme" aimed to explain the principles and aspirations of the new art form to a wider audience. It articulated key concepts such as the rejection of single-point perspective in favor of multiple viewpoints, allowing the artist to represent an object's total conceptual reality rather than just its fleeting visual appearance. The authors emphasized the intellectual nature of Cubism, portraying it as a profound rethinking of pictorial representation rooted in contemporary ideas about geometry, duration (influenced by philosopher Henri Bergson), and the dynamism of modern life.

The book distinguished Cubism from earlier art forms, arguing for its autonomy as a mode of expression concerned with the inherent qualities of painting – line, form, color, and composition – rather than mere imitation. Gleizes and Metzinger discussed the work of their contemporaries, including Picasso, Braque, Léger, Delaunay, Le Fauconnier, and Juan Gris, positioning their collective efforts within a coherent historical and theoretical context. Du "Cubisme" solidified Gleizes's reputation not just as a leading painter but also as a primary intellectual force behind the movement.

The Section d'Or and the Apex of Salon Cubism

The year 1912 marked a high point for the public manifestation of Cubism, culminating in the Salon de la Section d'Or exhibition held at the Galerie La Boétie in October. Organized primarily by the Duchamp brothers – Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and Marcel Duchamp – along with Gleizes and others, this exhibition brought together the major figures associated with Salon Cubism and related tendencies. It was the most comprehensive display of Cubist art to date, featuring over 200 works by some thirty artists.

Participants included Gleizes, Metzinger, the Duchamp brothers, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Francis Picabia, Alexander Archipenko, Roger de La Fresnaye, and František Kupka, among others. The name "Section d'Or" (Golden Section) alluded to the mathematical principles of harmony and proportion, reflecting the group's interest in underlying structures and intellectual rigor, distinguishing their approach from what they perceived as the more intuitive methods of Picasso and Braque.

Gleizes was a central figure in the Section d'Or, both as an organizer and a major exhibitor. He presented significant works like L'Homme au Balcon (Man on a Balcony, 1912) and the monumental Le Dépiquage des Moissons (Harvest Threshing, 1912). These paintings exemplify his mature Cubist style: large-scale compositions depicting scenes of modern life or rural labor, rendered with complex geometric faceting, dynamic rhythms, and a strong sense of structure that integrated figures and environment into a unified whole. Harvest Threshing, in particular, is considered one of the masterpieces of Salon Cubism, showcasing Gleizes's ambition to create a modern, epic form of painting.

War, Exile, and New Directions

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 abruptly disrupted the European avant-garde. Gleizes was mobilized into the French army and served near Toul. The experience of war deeply affected him, reinforcing his spiritual inclinations and his critique of materialism and nationalism. Demobilized in the autumn of 1915, he married the artist and writer Juliette Roche, daughter of a prominent politician, and shortly thereafter, they left wartime Europe.

They traveled first to New York City, arriving in the fall of 1915. The city's vibrant energy and towering architecture made a strong impression on Gleizes, inspiring works like his famous Brooklyn Bridge (1915), which captured the dynamism of the modern metropolis through a Cubist lens. New York was becoming a refuge for European artists fleeing the war, and Gleizes reconnected with figures like Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, becoming part of the circle around Walter Pach and the collector Walter Arensberg, which was instrumental in fostering the early American avant-garde and the Dada spirit in New York.

Gleizes and Roche spent time in Barcelona in 1916, where Gleizes had a solo exhibition organized by the art dealer Josep Dalmau. They returned to New York before finally sailing back to France in 1919. During his time abroad, Gleizes continued to paint and write, further developing his theories. His experiences in America and Spain broadened his perspective and contributed to a gradual shift in his art, moving away from the analytical fragmentation of earlier Cubism towards a more synthetic and rhythmic style. He also began to explore religious themes more explicitly, influenced by his deepening Catholic faith.

Towards Abstraction and Spiritual Art

Upon returning to post-war France, Gleizes entered a new phase of intense theoretical and artistic development. He distanced himself somewhat from the Parisian art scene, which was moving in directions like Surrealism that did not align with his evolving concerns. Instead, he focused on consolidating his own artistic philosophy, which increasingly emphasized the spiritual potential of abstract art.

In 1921, he published La Peinture et ses lois (Painting and Its Laws), a seminal text outlining his theory of "translation" and "rotation" as fundamental principles of pictorial composition. He argued that painting should derive its laws from the inherent properties of the flat canvas and the rhythmic movements perceived by the eye, rather than imitating external reality. This led him towards a non-representational style characterized by interlocking planes, rhythmic curves, and a focus on the dynamic interplay of form and color.

His work from the 1920s and 1930s became increasingly abstract, though often retaining a connection to underlying themes, frequently religious or philosophical. He sought an art that could embody universal spiritual truths, moving beyond the purely formal concerns of early Cubism. His style became characterized by broad, flat planes of color, often arranged in complex rotational patterns, creating a sense of monumental stability combined with dynamic energy. This approach set him apart from many other abstract artists of the period.

Gleizes's theories also found resonance abroad. His writings, particularly Du "Cubisme" and later essays, were studied at institutions like the Bauhaus in Germany, influencing figures associated with abstract art and design, even if his specific emphasis on spirituality differed from the more functionalist ethos often associated with the school (though figures like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee at the Bauhaus also explored spiritual dimensions).

Moly-Sabata: A Community for Art and Craft

In 1927, Gleizes realized his long-held dream of establishing another artistic community, purchasing a large house called Moly-Sabata in Sablons, near his wife's family home in the Rhône Valley. This community was conceived differently from the earlier Abbaye de Créteil. Moly-Sabata was intended as a place where artists and artisans could live and work together, reviving traditional crafts alongside modern artistic practices, all grounded in a shared spiritual, predominantly Catholic, framework.

Gleizes envisioned Moly-Sabata as a center for regenerating art and society through a return to fundamental principles of craft, community, and faith. He believed that the separation of art from craft and daily life was a symptom of modern alienation, which he sought to overcome. The community attracted various residents over the years, including potters, weavers, painters, and sculptors.

One notable figure associated with Moly-Sabata was the Australian-born ceramicist Anne Dangar. She arrived in 1930 and remained for the rest of her life, becoming a key member of the community. Dangar absorbed Gleizes's theories of Cubist composition based on rhythm and rotation and applied them creatively to pottery, developing a unique style that blended traditional peasant forms with modern abstract decoration. Her work exemplifies the integration of art and craft that Gleizes championed. Gleizes himself spent considerable time at Moly-Sabata, painting, writing, and guiding the community until his death.

Later Years, Legacy, and Influence

In his later career, Gleizes continued to refine his abstract style and deepen his exploration of religious themes. He became associated with the Abstraction-Création group in the 1930s, an association of abstract artists in Paris that included figures like Jean Hélion, Auguste Herbin, and briefly Theo van Doesburg. While sharing their commitment to non-representational art, Gleizes's spiritual and philosophical motivations often set him apart.

He undertook several large-scale mural projects, most notably for the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Paris World Fair) in 1937, where he decorated the Salon des Tuileries pavilion alongside Robert Delaunay and others. These murals allowed him to work on an architectural scale, integrating his rhythmic compositions into public spaces.

During World War II and the post-war years, Gleizes focused increasingly on religious subjects, creating paintings, drawings, and prints inspired by biblical narratives and Catholic doctrine. His late works include a series of powerful etchings illustrating Blaise Pascal's Pensées, reflecting a profound engagement with faith and philosophy. In 1947, a major retrospective exhibition of his work was held in Lyon, acknowledging his significant contribution to modern art.

Albert Gleizes passed away on June 23, 1953, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a key innovator of Cubism and developed a unique and enduring abstract language. As a theorist, his writings, especially Du "Cubisme", were crucial in defining and disseminating Cubist ideas. As an organizer and thinker, his efforts to create artistic communities like the Abbaye de Créteil and Moly-Sabata reflected a lifelong commitment to integrating art, life, and social or spiritual values.

His influence extended to numerous artists, both directly through teaching and collaboration (like Metzinger, Dangar) and indirectly through his widely read texts. Australian artists like Grace Crowley, who studied with Gleizes and André Lhote in Paris, brought Cubist principles back to their home country. While perhaps overshadowed in popular accounts by Picasso and Braque, Gleizes's role as a pioneer of Salon Cubism, a major theorist, and a developer of a distinct spiritual abstraction remains fundamental to understanding the complexity and richness of 20th-century modernism.

Artistic Style, Philosophy, and Controversies

Gleizes's artistic journey charts a clear evolution: from an early engagement with Impressionism, through a pivotal role in developing and theorizing Cubism, to the creation of a highly personal form of rhythmic, spiritual abstraction. Key elements of his mature style include the use of multiple perspectives, the breakdown of objects into geometric planes, an emphasis on the dynamism and rhythm of composition (often involving rotational movement), and, particularly in later years, the use of flat, clearly defined planes of color arranged in complex, harmonious structures.

His philosophy underpinned this stylistic development. He believed art should not merely imitate appearances but reveal underlying structures and universal truths. Initially influenced by socialist ideals and a desire for art relevant to modern collective life, his thinking became increasingly infused with Catholic spirituality. He saw abstract art not as mere decoration but as a potential vehicle for spiritual insight and a means to counteract the materialism he perceived in modern society.

Despite his importance, Gleizes's work and ideas were not without controversy. Some critics, particularly those championing the Picasso-Braque lineage, sometimes dismissed Salon Cubism as derivative or overly decorative. Gleizes's later abstract work, with its strong spiritual and theoretical underpinnings, was occasionally criticized as being too systematic or intellectual, lacking the spontaneity or emotional intensity valued by other strands of modernism. His insistence on integrating art with craft and religious principles also placed him outside the mainstream trajectory of secular, increasingly autonomous abstract art in the post-war era. His political and social views, evolving from early socialist sympathies towards a more traditionalist Catholic perspective, added another layer of complexity to his reception.

Conclusion

Albert Gleizes remains a figure of central importance in the history of modern art. As a co-founder of Cubism, he helped shape one of the most revolutionary movements of the 20th century. His collaboration with Jean Metzinger on Du "Cubisme" provided the movement with its first and arguably most influential theoretical voice. Beyond Cubism, his lifelong quest led him to develop a unique abstract language imbued with rhythm, structure, and profound spiritual conviction. Through his paintings, writings, and the communities he fostered, Gleizes consistently sought an art that was intellectually rigorous, socially relevant, and spiritually resonant. His work continues to be studied and appreciated for its formal innovation, theoretical depth, and unwavering commitment to the transformative power of art. He stands alongside figures like Picasso, Braque, Léger, Delaunay, Gris, and Kandinsky as a key architect of artistic modernity.