Introduction: A Pioneer's Emergence

Mainie Harriet Jellett stands as a colossus in the narrative of Irish art history. Born in Dublin in 1897 and passing away prematurely in 1944, her life spanned a period of immense cultural and political change in Ireland. Against a backdrop of national awakening and artistic conservatism, Jellett became a primary force in introducing and championing modern art, particularly Cubism and abstraction, to a frequently resistant Irish audience. Her unwavering commitment to her artistic vision, coupled with her intellectual rigour and advocacy, fundamentally reshaped the landscape of Irish art, paving the way for subsequent generations of modern artists. She was not merely a painter but an educator, a theorist, and a cultural catalyst whose influence continues to resonate.

Formative Years: Dublin Foundations

Jellett's journey into art began within a privileged and culturally rich environment in Dublin. Her father, William Morgan Jellett, was a barrister and later a Unionist Member of Parliament, while her mother, Janet McKenzie Stokes, was an accomplished musician. This blend of legal prominence and artistic sensitivity in her household likely fostered an appreciation for both structure and creativity from an early age. Her formal art education commenced early; by the age of eleven, she was receiving instruction from notable figures in the Dublin art scene, including Elizabeth Yeats, sister of the poet W.B. Yeats and the painter Jack B. Yeats, and Mary Manning, laying the groundwork for her future artistic pursuits.

Furthering her training, Jellett enrolled at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin (now the National College of Art and Design). Here, she honed her skills under the tutelage of prominent Irish artists, including William Orpen, although his direct influence on her later, more radical style is debatable. She demonstrated considerable talent during these early years, absorbing the academic traditions while perhaps already sensing the limitations of conventional approaches. Her time at the Metropolitan School provided her with a solid technical grounding, essential even for an artist who would later deconstruct traditional forms.

London Studies: Encountering Sickert

Seeking broader horizons, Jellett moved to London around 1917-1919. She enrolled at the prestigious Westminster Technical Institute (later the Westminster School of Art), a significant step that exposed her to the currents of British art. Crucially, she studied under Walter Sickert, a towering figure in British painting and a key member of the Camden Town Group. Sickert, known for his muted palette, depictions of everyday urban life, and connection to French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the work of Edgar Degas, offered a different perspective from her Dublin training.

While Jellett's mature style would diverge significantly from Sickert's gritty realism, his emphasis on structure, composition, and disciplined observation likely left an impression. Studying with Sickert provided exposure to a more cosmopolitan art world and contemporary European ideas, even if filtered through his particular lens. It was also during her time in London that she solidified her lifelong friendship and artistic partnership with fellow Irish artist Evie Hone, a relationship that would prove central to both their lives and the development of modern art in Ireland.

The Parisian Crucible: Lhote and Gleizes

The decisive turning point in Jellett's artistic development occurred in Paris. Accompanied by Evie Hone, she travelled to the French capital, the undisputed centre of the avant-garde, around 1921. Initially, they sought out André Lhote, a painter and influential teacher who had developed his own systematic interpretation of Cubism. Lhote aimed to reconcile Cubist innovations with classical composition, offering a structured, almost academic approach to understanding the geometric breakdown of form pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. His studio attracted numerous international students seeking to grasp the principles of modern art.

While Lhote provided a valuable framework, Jellett and Hone soon felt the need for a deeper, more radical immersion in Cubist principles. They sought out Albert Gleizes, a leading figure of the Cubist movement alongside Jean Metzinger (with whom he co-authored the seminal text Du "Cubisme" in 1912). Gleizes had moved towards a more abstract, non-objective, and theoretically grounded form of Cubism, distinct from the earlier analytical and synthetic phases of Picasso and Braque. His teaching emphasised a rigorous system of 'translation and rotation' – planar movements across the canvas – aiming for a dynamic, rhythmic abstraction rooted in universal principles rather than direct observation.

Embracing Abstraction: A New Visual Language

Under Gleizes's demanding tutelage, Jellett underwent a profound artistic transformation. She diligently absorbed his complex theories, translating them into a disciplined studio practice. This involved methodical exercises in breaking down objects into geometric planes and reorganising them on the canvas according to principles of rhythm and movement. It was a process of unlearning traditional representation and constructing a new visual language based on abstract relationships of form and colour. Gleizes's emphasis on the spiritual potential of abstract art also resonated with Jellett's own inclinations.

This period marked Jellett's definitive break from representational art and her wholehearted embrace of abstraction. She learned to see the canvas not as a window onto the world, but as a surface on which to build dynamic compositions using line, plane, and colour. Her work from this time shows a clear debt to Gleizes's system, characterised by interlocking geometric shapes, a controlled palette, and a powerful sense of underlying structure and rhythm. This rigorous training provided the foundation for her unique contribution to modernism.

Introducing Modernism to Ireland: A Contentious Return

Armed with her newfound artistic convictions and a portfolio of abstract works, Jellett returned to Dublin in the early 1920s. Ireland, then grappling with the aftermath of the War of Independence and the Civil War, possessed an art establishment largely dominated by the conservative Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA). While artists like Jack B. Yeats explored expressive figuration and Paul Henry captured iconic landscapes, abstract art was virtually unknown and viewed with suspicion, often dismissed as foreign and incomprehensible.

Jellett's decision to exhibit her abstract work in this environment was a bold, almost provocative act. In 1923, she and Evie Hone submitted paintings executed in their new Cubist-influenced style to the Dublin Painters' Society group exhibition. Jellett's contribution, titled Decoration, became an instant focal point for controversy and critical hostility. It represented one of the very first purely abstract paintings to be publicly displayed in Ireland, challenging established aesthetic norms head-on.

The 'Decoration' Scandal and Critical Backlash

The reaction to Decoration was overwhelmingly negative, bordering on vitriolic. Critics struggled to comprehend its non-representational nature. The poet and painter George Russell (writing as 'AE'), a prominent figure in the Irish literary revival, famously dismissed the work in the Irish Statesman, questioning its artistic merit and labelling aspects of modern art as "sub-human". Other critics employed equally dismissive language, referring to the painting with terms like "artistic malaria" or comparing it unfavourably to patterned linoleum.

This hostile reception highlighted the deep chasm between the European avant-garde and the prevailing artistic tastes in Ireland. Jellett found herself at the forefront of a battle for modernism's acceptance. Far from being deterred, the controversy seemed to strengthen her resolve. She became a vocal defender of her artistic principles, arguing for the validity and importance of abstract art through lectures, articles, and broadcasts over the subsequent years. The Decoration incident, though initially damaging, cemented Jellett's position as a pioneer willing to challenge the status quo.

Forging a Unique Style: Synthesis and Spirit

Following the initial shockwaves of her return, Jellett continued to develop her artistic style, moving beyond a strict adherence to Gleizes's methods to forge a more personal visual language. While retaining the core principles of Cubist structure and abstraction learned in Paris, she began to integrate elements drawn from her Irish heritage and her own spiritual convictions. Her work became less rigidly systematic and more intuitive, characterised by a richer use of colour and a more fluid sense of rhythm.

She drew inspiration from early Irish Christian art, particularly the intricate interlace patterns found in Celtic manuscripts like the Book of Kells and the dynamic forms of High Crosses. This fusion of ancient Irish aesthetics with modern European abstraction resulted in a unique synthesis. Jellett explored the symbolic and emotional power of colour, often employing vibrant hues arranged in complex, harmonious compositions. Religious themes also became increasingly prominent in her work, treated not in a traditionally narrative way, but through abstract forms intended to convey spiritual feeling and universal truths.

Key Works: Milestones in Abstraction

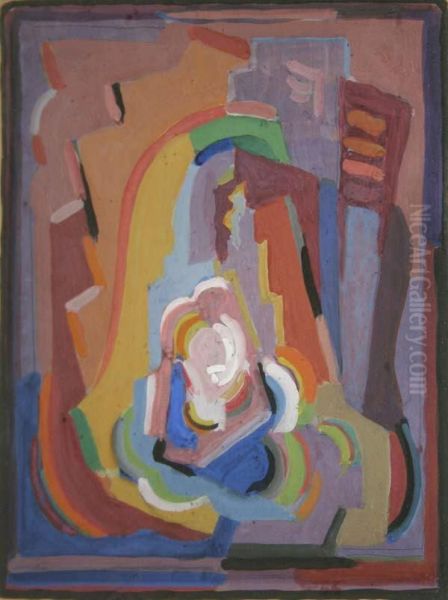

Several key works mark the evolution of Jellett's distinctive style. Decoration (1923), despite its controversial debut, remains a landmark painting – an early declaration of abstract principles in an Irish context, showcasing her understanding of Gleizes's planar analysis. Later works demonstrate her growing independence and synthesis of influences.

Composition (c. 1935) exemplifies her mature abstract style, featuring dynamic, interlocking shapes and a vibrant palette, creating a powerful sense of rhythm and visual energy entirely divorced from representation. Achill Horses (1941) shows her applying abstract principles to a recognisable subject, albeit highly stylised. The horses are reduced to powerful geometric forms, capturing their energy and movement through dynamic lines and bold colour contrasts, demonstrating her ability to bridge the gap between abstraction and observed reality. Works with religious titles, such as The Ninth Hour or studies for The Virgin of Éire, further illustrate her exploration of spiritual themes through abstract means, using colour and form to evoke reverence and contemplation.

Advocate and Educator: Spreading the Modernist Gospel

Mainie Jellett was more than just a painter; she was a tireless advocate and educator, playing a crucial role in fostering an understanding and appreciation of modern art in Ireland. Recognising the resistance and lack of comprehension that greeted her work, she embarked on a mission to explain the principles and significance of the modern movement. She delivered numerous lectures across the country, wrote articles for journals, and utilized the relatively new medium of radio broadcasting to reach a wider audience.

Her arguments were articulate and intellectually grounded, often drawing parallels between the structure of modern painting and music (perhaps influenced by her mother's background). She defended abstraction not as a rejection of tradition, but as a continuation of art's essential search for form and expression, relevant to the contemporary world. She positioned modern art as having spiritual depth and universal relevance, countering accusations of it being merely decorative or meaningless. Through her advocacy, Jellett became a public intellectual, shaping the discourse around art in Ireland.

Collaboration and Design: Beyond the Canvas

Jellett's artistic activities extended beyond easel painting. Her lifelong collaboration with Evie Hone was fundamental. They shared studios, travelled together, exhibited together, and provided crucial mutual support in the face of criticism. Their artistic paths, while parallel in their embrace of modernism, eventually diverged, with Hone later focusing primarily on stained glass, yet their bond remained strong.

Jellett herself engaged in design work, demonstrating a belief in the integration of art into everyday life, a principle shared by movements like the Bauhaus (though her direct connection is unclear). Notably, she designed carpets, some of which were reportedly produced in collaboration with the renowned modernist designer and architect Eileen Gray, another Irishwoman who achieved international fame primarily in Paris. These designs translated her abstract compositional principles and colour sense into functional objects. There is also evidence suggesting she undertook some work or designs related to stained glass, possibly connected to Sarah Purser's Dublin-based cooperative studio, An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass), though Hone became more famously associated with this medium.

The Irish Exhibition of Living Art: A Platform for the New

One of Jellett's most significant contributions to the infrastructure of Irish art was her central role in founding the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA) in 1943. By the early 1940s, frustration had grown among modernist artists regarding the perceived conservatism and exclusivity of the RHA annual exhibitions, which offered limited space for experimental work. Jellett, along with Evie Hone, Louis le Brocquy, Norah McGuinness, Jack Hanlon, and others, decided to create an alternative venue.

Jellett served as the first chairperson of the IELA. The exhibition aimed to provide a non-juried platform (initially, later modified) for contemporary art in Ireland, showcasing a diverse range of styles beyond academic realism, including abstraction and expressionism. The IELA quickly became the most important event for progressive art in Ireland, offering crucial exposure and encouragement to younger artists and significantly challenging the RHA's dominance. Its establishment marked a major victory in the campaign for modernism's acceptance and vitality in Ireland, a direct result of the advocacy Jellett had pursued for two decades.

International Recognition and Participation

While deeply committed to developing modern art within Ireland, Jellett also maintained connections with the international art world and achieved recognition beyond Irish shores. Her training with Lhote and Gleizes in Paris inherently placed her within a European context. Her work was included in various international group exhibitions in cities like London, Paris, and Brussels.

She represented Ireland in the art competitions held as part of the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928 (though records of specific entries can be elusive). More significantly, her work was featured in the Irish pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair, showcasing contemporary Irish culture to a global audience. She also participated in the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow. These international exposures helped to validate her work and demonstrate that Irish artists were engaging with contemporary European movements, countering any perception of Ireland as merely provincial.

Later Life, Illness, and Enduring Legacy

Mainie Jellett continued to paint and advocate for modern art throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s. She remained a central figure in the Dublin art world, respected for her talent, intellect, and unwavering commitment, even by those who did not fully embrace her style. Her leadership in establishing the IELA in 1943 was a culmination of her efforts.

Tragically, her career was cut short. She was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and passed away in Dublin on February 16, 1944, at the relatively young age of 46. Her death was a significant loss to the Irish art community. Her friend Elizabeth Yeats wrote a moving obituary, testament to the high regard in which she was held. To honour her memory and contribution, the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland established the Mainie Jellett Memorial Scholarship, aimed at supporting aspiring art students, ensuring her legacy would continue to foster artistic development in Ireland.

Conclusion: A Foundational Figure

Mainie Harriet Jellett's impact on Irish art is undeniable and profound. She was arguably the single most important figure in introducing and establishing modernist principles, particularly Cubism and abstraction, in Ireland during the first half of the 20th century. Facing considerable opposition, she not only produced a significant body of innovative work but also tirelessly championed the cause of modern art through her teaching, writing, and public advocacy. Her collaboration with Evie Hone, her role in founding the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, and her engagement with international currents all contributed to broadening the horizons of Irish art. Though her life was tragically short, Mainie Jellett laid the foundations upon which much of subsequent Irish modern and contemporary art has been built. She remains a pivotal and inspirational figure, an artist of conviction, courage, and enduring significance.