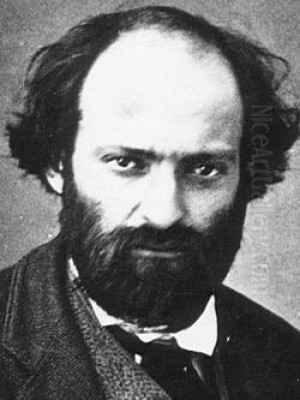

Paul Cézanne, born on January 19, 1839, in Aix-en-Provence, France, and passing away on October 22, 1906, stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of Western art. A pivotal Post-Impressionist painter, his work formed a crucial bridge between the transient concerns of Impressionism and the more structured, analytical approaches of 20th-century art movements, most notably Cubism. His relentless exploration of form, color, and perception earned him the posthumous title "Father of Modern Art," a testament to his profound and lasting impact. This article delves into the life, work, artistic philosophy, and enduring legacy of this complex and revolutionary artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Paul Cézanne was born into relative prosperity. His father, Louis-Auguste Cézanne, was a co-founder of a successful banking firm, Cézanne & Cabassol. Initially a hat maker, Louis-Auguste was ambitious and somewhat authoritarian, harbouring aspirations for his son to follow a respectable profession, preferably law or banking, to secure the family's social standing. In contrast, Cézanne's mother, Anne Elisabeth Honorine Aubert, was described as lively, romantic, and supportive, providing a counterbalance to the stern paternal influence. Paul also had two younger sisters, Marie and Rose, with whom he shared a closer bond, particularly with Marie.

Despite his father's wishes, the young Cézanne displayed an early passion for the arts. His formal education included attendance at the Collège Bourbon in Aix (now Collège Mignet). It was here, beginning in 1852, that he formed a close and formative friendship with Émile Zola, the future novelist, and Baptistin Baille, who would later pursue science. The trio became known as "Les Inséparables" (The Inseparables), spending their youth exploring the Provençal countryside, swimming, hunting, and engaging in passionate discussions about literature and art, particularly the Romantic poets. Zola, in particular, encouraged Cézanne's artistic inclinations.

Cézanne initially attempted to placate his father by enrolling in the law school at the University of Aix-en-Provence in 1858, while simultaneously taking drawing lessons at the local Free Municipal School of Drawing. However, his legal studies proved unsatisfying. His true desire lay in painting. After repeated entreaties, and perhaps with the quiet support of his mother, Cézanne finally persuaded his father to allow him to travel to Paris in 1861 to pursue an artistic career. Louis-Auguste, though skeptical, provided a modest allowance.

Parisian Connections and Impressionist Ties

Cézanne's initial foray into the Parisian art world was challenging. He attended the informal Académie Suisse, where artists could work from live models without formal instruction. There, he met Camille Pissarro, a slightly older artist who would become a crucial mentor and lifelong friend. He also encountered other aspiring painters who would later form the core of the Impressionist group, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley. However, Cézanne's early work, characterized by dark palettes, thick impasto, and often violent or romantic subject matter, differed significantly from the emerging Impressionist aesthetic.

Feeling discouraged and perhaps overwhelmed, Cézanne returned to Aix after only a few months, briefly working in his father's bank. The pull of art was too strong, however, and he returned to Paris the following year, 1862. He reconnected with his artist friends and submitted works to the official Salon, the prestigious state-sponsored exhibition, only to face repeated rejection. This pattern of rejection by the art establishment would continue for much of his career, fostering a sense of isolation and reinforcing his independent spirit.

The relationship with Émile Zola remained important during these years, though it would eventually sour. Zola, achieving literary fame, became a champion of the Impressionists, but his understanding of Cézanne's unique artistic struggles seemed limited. The decisive break came in 1886 with the publication of Zola's novel L'Œuvre (The Masterpiece). The novel's protagonist, Claude Lantier, is a largely failed, innovative painter whose struggles bear some resemblance to Cézanne's own. Cézanne interpreted the character as a thinly veiled, negative portrayal of himself and his artistic ambitions, leading to the painful termination of their long friendship.

Despite his often solitary nature, Cézanne maintained significant connections within the avant-garde art community. His relationship with Camille Pissarro was particularly vital. During the early 1870s, Cézanne spent considerable time working alongside Pissarro in Pontoise and Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris. Under Pissarro's influence, Cézanne's palette lightened, he adopted the broken brushwork characteristic of Impressionism, and he increasingly focused on direct observation of nature (sur le motif). Pissarro provided invaluable encouragement and technical guidance. Cézanne later referred to Pissarro as "a father for me," and acknowledged him as "the first Impressionist." He even copied one of Pissarro's landscapes, Louveciennes, as a learning exercise.

Cézanne participated in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, held at the studio of the photographer Nadar, showing three paintings, including A Modern Olympia (a response to Édouard Manet's controversial work) and House of the Hanged Man. He also participated in the third exhibition in 1877 with sixteen works. However, his paintings often received the harshest criticism, being perceived as crude and unfinished even compared to the works of Monet or Renoir. While associated with the Impressionists and sharing their interest in contemporary life and landscape, Cézanne's artistic goals were fundamentally different. He sought structure and permanence beneath the fleeting effects of light that captivated many of his peers. He also maintained contact with Edgar Degas, who admired and collected Cézanne's work, and occasionally interacted with Gustave Courbet, the leading figure of Realism.

Developing a Unique Vision: The Cézanne Style

Cézanne famously stated his ambition was to "make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums." While he learned much from the Impressionists, particularly Pissarro, about color theory and painting outdoors, he felt their focus on capturing momentary sensations lacked formal rigor. He sought to combine the vibrant color and direct observation of Impressionism with a sense of classical composition and underlying structure.

His method involved intense, prolonged observation and analysis. He believed that underlying the apparent chaos of nature were fundamental geometric forms. In a famous letter to the painter Émile Bernard in 1904, he advised, "Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything in proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point." This was not a literal instruction to reduce everything to simple geometry, but rather a way of thinking about the underlying structure and volume of objects in space.

Cézanne developed a distinctive technique often referred to as "constructive brushstroke." He applied paint in deliberate, parallel, hatched strokes, building up forms and suggesting volume through subtle shifts in color rather than traditional modeling with light and shadow (chiaroscuro). He believed that "Color is the place where our brain and the universe meet." For Cézanne, drawing and color were inseparable; as color reached its richness, form attained its fullness. This meticulous application of paint resulted in surfaces that emphasized the two-dimensionality of the canvas while simultaneously creating a powerful sense of three-dimensional form and spatial depth.

His approach to perspective was also revolutionary. Rejecting the single, fixed viewpoint of traditional Renaissance perspective, Cézanne often incorporated multiple viewpoints within a single composition, particularly in his still lifes. Tabletops might tilt forward, objects might appear slightly distorted or seen from different angles simultaneously. This was not due to a lack of skill, but a deliberate attempt to represent the experience of seeing – the way the eye moves and scans, gathering information over time – and to create a more dynamic and structurally sound composition on the flat canvas. His process was notoriously slow and painstaking, requiring intense concentration as he sought the precise color relationships and formal arrangements to realize his "sensation" before nature.

Masterpieces and Major Themes

Cézanne worked across the traditional genres of landscape, still life, and figure painting, bringing his unique analytical approach to each. His output was substantial, leaving behind over 900 oil paintings and more than 1100 watercolors and drawings.

Still Lifes: Cézanne elevated still life from a minor genre to a major vehicle for artistic exploration. Works like The Basket of Apples (c. 1893) or Still Life with Commode (c. 1888) exemplify his innovations. Apples, pears, onions, jugs, and drapery become subjects for intense formal investigation. He masterfully arranges objects, exploring their shapes, volumes, and spatial relationships. The seemingly "incorrect" perspective, with tilted tables and shifting viewpoints, creates a dynamic tension and forces the viewer to engage actively with the composition. His use of color modulation builds form and creates a palpable sense of weight and presence, giving these everyday objects a monumental quality, what he termed a "quiet life."

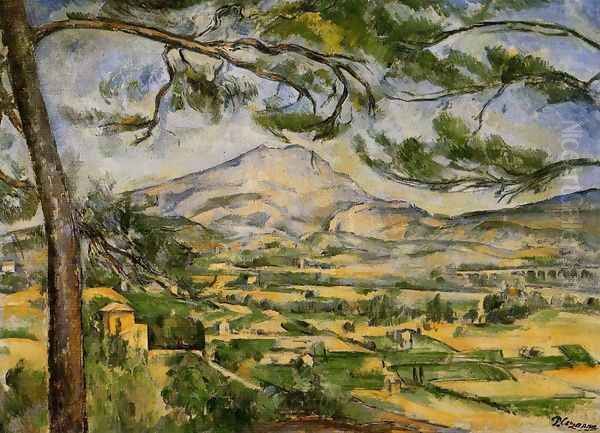

Landscapes: The landscape of his native Provence was a constant source of inspiration. His most famous landscape subject is Mont Sainte-Victoire, a mountain near Aix-en-Provence which he painted over 60 times in oil and watercolor. In these series, particularly the later works from the early 1900s, we see his style evolve towards greater abstraction. The mountain and surrounding landscape are broken down into facets of color – blues, greens, ochres, violets – that simultaneously represent rock, foliage, sky, and atmosphere, while also emphasizing the underlying geometric structure of the scene. These paintings convey both the specific character of the Provençal landscape and a timeless, almost geological sense of permanence. Other important landscape locations include L'Estaque, a coastal village near Marseille, and the grounds of the Château Noir.

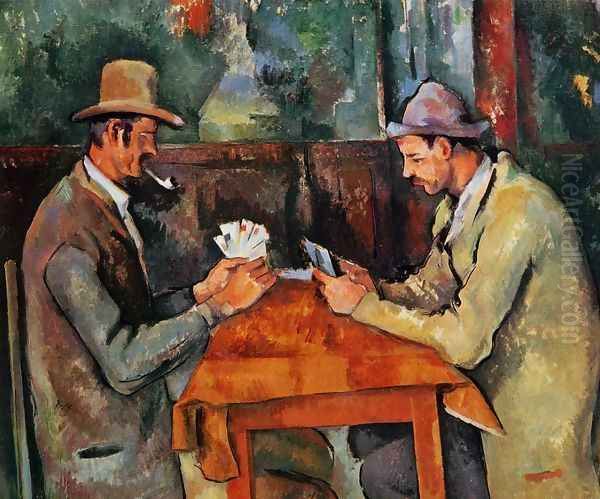

Figure Painting: Cézanne's figure paintings often possess a similar sense of gravity and structure as his still lifes and landscapes. The Card Players series (early 1890s), depicting Provençal peasants engrossed in their game, is among his most celebrated works. The figures are simplified, almost sculptural, rendered with sober colors and deliberate brushwork. There is a profound sense of quiet concentration and timeless ritual. His portraits, including numerous self-portraits and depictions of his wife, Hortense Fiquet, are often psychologically penetrating despite their formal rigor.

His series of Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), particularly the three large versions painted late in his life, represent a culmination of his efforts to integrate the human figure into a landscape setting. These works feature abstracted, often angular nudes arranged in complex, classically inspired compositions beneath arching trees. They are not realistic depictions but rather explorations of form, rhythm, and the relationship between humanity and nature, pushing towards a more modern, less naturalistic representation of the figure that would deeply influence later artists. Other notable works include A Modern Olympia, Château Noir, The Forest, and the haunting late works featuring skulls, such as Pyramid of Skulls (c. 1901).

The Solitary Master of Aix

As he grew older, Cézanne spent increasingly more time in Aix-en-Provence, distancing himself from the Parisian art world. He inherited the family estate, Jas de Bouffan, after his father's death in 1886, which provided financial security but also perhaps increased his isolation. His personality contributed to this withdrawal; he was known to be sensitive, irritable, suspicious, and prone to depression, making sustained social interaction difficult. He developed diabetes in the 1890s, further impacting his health and temperament.

His personal life was also complex. He met Marie-Hortense Fiquet, a bookbinder and model, in Paris around 1869. They had a son, Paul, born in 1872. For many years, Cézanne kept his relationship with Hortense and their son a secret from his stern father, fearing disapproval and the potential loss of his allowance. He divided his time between Paris, Aix, and other locations, often living apart from Hortense and Paul. He finally married Hortense in 1886, shortly before his father's death, likely to ensure his son's legitimacy and inheritance rights. Their relationship appears to have been difficult, though Hortense frequently sat for portraits.

In his later years, Cézanne became something of a legend in Aix, a reclusive figure dedicated entirely to his art. He sold the Jas de Bouffan in 1899 after his mother's death and eventually built a dedicated studio on the Chemin des Lauves, overlooking Aix, in 1901. Here, he worked relentlessly, rising early each day to paint, either in the studio or outdoors in the surrounding countryside, carrying his equipment himself or hiring a carriage. He remained deeply committed to his artistic quest, seeking to realize his "petite sensation" – his unique perception of the world translated into paint. Despite his growing reputation among a small circle of younger artists and collectors, he remained largely isolated from mainstream recognition.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Although Cézanne experienced limited success during his lifetime, his influence on the course of 20th-century art was immense and transformative. His death in 1906 coincided with a growing appreciation of his work. A major retrospective exhibition held at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1907 had a profound impact on a generation of younger artists.

His emphasis on underlying structure, his reduction of natural forms to geometric essentials, and his use of multiple viewpoints directly paved the way for Cubism. Both Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque acknowledged their profound debt to Cézanne. Picasso famously called him "the father of us all," while Braque remarked that Cézanne's work "made me feel as if someone was drinking my blood." The early Cubist landscapes of Braque, painted at L'Estaque (a location Cézanne also favored), clearly show this influence.

Henri Matisse, the leading figure of Fauvism, also deeply admired Cézanne, acquiring one of his Bathers paintings. While the Fauves focused more on expressive color, Cézanne's liberation of color from purely descriptive purposes and his emphasis on the structural role of color were foundational. His work provided a crucial alternative to the purely optical concerns of Impressionism, demonstrating how painting could be a construction, an autonomous reality, rather than just a reflection of the visible world.

Beyond Cubism and Fauvism, Cézanne's influence extended to numerous other artists and movements, including Expressionism and abstract art. His rigorous analysis of form, his innovative use of color, and his dedication to the integrity of the painting as an object resonated throughout modern art. Artists like Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and many others looked to Cézanne as a pioneer who had fundamentally changed the possibilities of painting. His fellow Post-Impressionists, such as Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, also sought new directions beyond Impressionism, but Cézanne's specific focus on structure and analytical observation set him apart and proved particularly fertile for future developments.

Final Years and Posthumous Recognition

Cézanne continued to work with unwavering dedication until the very end of his life. His late works, particularly the watercolors, often display a remarkable freedom and abstraction, where patches of color seem to float independently while still suggesting form and light. He remained committed to working outdoors, directly confronting nature.

On October 15, 1906, while painting outside in the fields near Aix, Cézanne was caught in a severe thunderstorm. He continued working for two hours before collapsing. He was taken home in a laundry cart but developed pneumonia. Despite a brief rally, he died a few days later, on October 22, 1906, at the age of 67.

While recognition had been slow in coming, by the time of his death, Cézanne was already revered by many avant-garde artists. The art dealer Ambroise Vollard had given him his first solo exhibition in Paris in 1895, which brought his work to wider attention. The 1907 retrospective solidified his reputation as a master. Today, his paintings are highlights of major museum collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the National Gallery in London. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as those held at the Art Institute of Chicago and Tate Modern, continue to explore the depth and complexity of his achievement.

Paul Cézanne's legacy is that of a revolutionary artist who fundamentally altered the way we see and represent the world. His patient, analytical, and deeply personal quest to create an art of structure, harmony, and permanence provided the foundation upon which much of modern art was built. He remains a towering figure, whose work continues to challenge and inspire artists and viewers alike.