Albert Marquet stands as a significant yet often understated figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century French art. Born in Bordeaux on March 27, 1875, and passing away in Paris on June 14, 1947, his life spanned a period of radical artistic transformation. While initially associated with the explosive color and energy of Fauvism, Marquet forged a distinct and enduring path, dedicating himself to a more intimate, observational form of naturalism. He became renowned for his sensitive depictions of landscapes, particularly the waterways of Paris, bustling French ports, and the luminous shores of North Africa, all rendered with a masterful understanding of light, atmosphere, and tonal harmony. His lifelong friendship with Henri Matisse provides a key thread through modern art history, yet Marquet's quiet dedication and unique vision secured his own important place.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Albert Marquet's journey into art began not with academic brilliance in traditional subjects, but with an innate passion for drawing. From a young age in Bordeaux, his sketchbooks overflowed with observations, revealing a talent that compensated for his otherwise unremarkable school performance. Crucially, his mother recognized and encouraged this artistic inclination, supporting his move to Paris in 1890 to pursue formal training.

He enrolled at the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (National School of Decorative Arts). This move proved pivotal, not just for his education, but because it was here he met a fellow student who would become his closest friend and artistic confidant for nearly half a century: Henri Matisse. Their bond, forged in these early student years, would endure through vastly different artistic trajectories and personal fortunes.

Together, Marquet and Matisse sought further instruction, entering the École des Beaux-Arts in 1892. They joined the studio of Gustave Moreau, a Symbolist painter deeply respected for his imaginative compositions and rich color sense, himself an inheritor of the Romantic tradition of Eugène Delacroix. Moreau was an unconventional but inspiring teacher, known for encouraging his students' individual temperaments rather than imposing a rigid style. He urged them to study the Old Masters in the Louvre but also to find their own voice. This environment nurtured not only Marquet and Matisse but also other future talents like Georges Rouault and Henri Evenepoel. Moreau's emphasis on color and personal expression undoubtedly left an imprint on Marquet's developing sensibilities, even as he moved towards landscape.

The Crucible of Fauvism

The early years of the 20th century in Paris were a ferment of artistic innovation. Marquet and Matisse, often sharing studio space, were at the heart of a developing movement that would soon shock the art world. They, along with artists like André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Kees van Dongen, began experimenting with bold, non-naturalistic color and simplified forms, pushing beyond the boundaries of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Marquet participated in early group exhibitions, notably at the Salon des Indépendants. However, the defining moment came at the Salon d'Automne in 1905. In a room filled with canvases blazing with intense hues and seemingly wild brushwork by Marquet, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Raoul Dufy, and others, the critic Louis Vauxcelles famously exclaimed they were among "Donatello au milieu des fauves!" (Donatello among the wild beasts!). The name stuck, and Fauvism was born.

Marquet's works from this period, while sharing the Fauvist enthusiasm for vibrant color and decorative qualities, often retained a stronger sense of structure and tonal balance compared to the more exuberant canvases of Vlaminck or Derain. His Fauvist paintings frequently depicted Parisian scenes, flags flying on Bastille Day, or posters adding patches of pure color, but the underlying drawing and compositional solidity remained evident. He was a core member of the group, contributing significantly to its impact, even if his temperament leaned towards quieter observation.

Forging an Independent Path: Towards Naturalism

While Marquet was integral to the Fauvist moment, his association with its most radical phase was relatively brief. Even during his Fauvist years, a certain restraint and a deep-seated connection to observed reality distinguished his work. Gradually, his palette softened, moving away from the high-keyed, arbitrary colors of Fauvism towards more nuanced, atmospheric tones that captured specific conditions of light and weather.

This shift did not represent a rejection of his earlier explorations or his friendship with Matisse, which remained steadfast. Rather, it was an evolution towards a style that better suited his contemplative personality and his profound interest in the subtleties of the visual world. He became less concerned with shocking the viewer with color and more focused on conveying the mood and essence of a place through carefully balanced compositions and harmonious color relationships.

His preferred subjects became landscapes and cityscapes, often viewed from a high vantage point – a window in his Paris apartment overlooking the Seine, or a hotel room gazing down upon a busy harbor. This elevated perspective allowed for broad, panoramic views, emphasizing the patterns of rivers, bridges, docks, and streets, while simplifying details and focusing on the interplay of large shapes and tonal masses. This approach echoed certain compositional strategies of Japanese prints, which had influenced earlier artists like Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but Marquet adapted it to his own quiet, observational ends.

Paris: The Enduring Muse

Paris, particularly the River Seine and its surroundings, remained a constant source of inspiration throughout Marquet's career. He painted the city in all seasons and weather conditions, capturing its unique atmosphere with remarkable sensitivity. From his various apartments and studios, often located near the river, he had commanding views of iconic landmarks.

He painted Notre Dame cathedral repeatedly, not as a detailed architectural study, but as a form emerging from the misty Parisian air, reflected in the water below. The bridges of Paris – the Pont Neuf, the Pont Saint-Michel, the Pont des Arts – became signature motifs. His 1906 painting, The Pont Neuf, executed during his Fauvist period but already showing his characteristic structural sense, is considered a major work, capturing the bustling life of the bridge and the river beneath a wide expanse of sky.

Marquet excelled at rendering the specific light of Paris: the soft grey haze of overcast days, the damp sheen on pavements after rain, the low, golden light of winter afternoons. Unlike the Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who focused on capturing fleeting moments with broken brushwork, Marquet sought a more stable, synthesized view, using broad areas of color and tone to convey the enduring character of the city. His Paris is often quiet, even melancholic, emphasizing the relationship between water, stone, and sky. His depictions offer a distinct vision compared to the bustling street scenes of Pissarro or the later, more architecturally focused views of Maurice Utrillo.

The Call of the Sea: Ports and Harbors

Beyond Paris, Marquet was deeply drawn to the life and atmosphere of ports. His extensive travels took him to numerous harbor towns across France and Europe. Le Havre, Rouen, Marseille, Honfleur, Naples, Venice, Hamburg, Rotterdam, Stockholm – all found their way onto his canvases. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture the essence of these maritime environments.

He painted the docks, the ships (from small fishing boats to larger steamers), the cranes, the warehouses, and always, the water. Water, in its myriad forms, was perhaps his most constant subject. He masterfully rendered its surface textures – the calm, reflective sheen of a sheltered basin, the choppy grey waves of the open sea, the murky waters of an industrial port. He paid close attention to reflections, using them to anchor his compositions and create depth, capturing the way light interacts with the water's surface.

His port scenes often share the high viewpoint of his Paris paintings, allowing him to organize the complex elements of the harbor into coherent, balanced compositions. There's a sense of order and tranquility even in these busy settings. While depicting scenes of commerce and transit, the human element is often downplayed or integrated into the overall pattern of shapes and colors. His work in this genre invites comparison with earlier marine painters like Eugène Boudin, who also excelled at capturing coastal light and atmosphere, though Marquet's style is distinctly modern in its simplification and tonal focus.

North Africa: A Different Light, A New Home

Marquet's travels frequently took him south, across the Mediterranean to North Africa. He developed a particular affinity for Algeria, visiting repeatedly and eventually living in Algiers for extended periods, including during World War II. He also painted in neighboring Tunisia, capturing scenes in Tunis and the port of La Goulette.

The intense light of North Africa offered a different challenge and inspiration compared to the softer, more diffused light of Northern Europe. While his palette might brighten in response to the Mediterranean sun, Marquet avoided exoticism or overly dramatic effects. His North African paintings retain his characteristic subtlety and focus on tonal harmony. He painted the harbors of Algiers, the white buildings cascading down to the blue sea, the daily life observed from his window.

It was in Algiers that Marquet met Marcelle Martin, who would become his wife in 1923. Their relationship provided stability and support for the artist. Marcelle took charge of managing his practical affairs, dealing with galleries and collectors, allowing the introverted Marquet to dedicate himself more fully to his painting. His time in North Africa was thus significant both personally and artistically, providing a rich source of subjects rendered with his signature blend of observation and simplification.

Voyages Further Afield

Marquet's wanderlust was not confined to France and North Africa. His career was punctuated by numerous trips across Europe. He painted canals in Holland, capturing the unique Dutch light and watery landscapes. He visited Germany, painting the bustling port of Hamburg. Italy, particularly Venice with its canals and distinctive light, provided another rich source of inspiration. He traveled to Scandinavia, capturing the northern light on the waters around Stockholm.

Evidence suggests he also visited Russia before the Revolution, likely drawn by the burgeoning collections of modern French art amassed by Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, which included significant works by Matisse and other contemporaries. These travels constantly refreshed his vision, providing new motifs and variations on his core themes of water, light, and landscape. Each location was filtered through his consistent artistic sensibility, resulting in works that are unmistakably Marquet's, whether depicting the Seine, the Bay of Algiers, or a Venetian canal.

Intimate Views: Nudes and Portraits

While primarily celebrated as a landscape painter, Marquet also produced significant work in other genres, notably female nudes and portraits. Between approximately 1910 and 1914, he created a remarkable series of nude studies. These works differ markedly from his landscapes; they are intimate interior scenes, often depicting a single model in a studio setting.

These nudes are characterized by their directness and lack of idealization. Marquet focused on the solid forms of the body, the play of light and shadow across skin, and the relationship between the figure and its immediate surroundings. The palette is often subdued, emphasizing tonal contrasts rather than bright color. Compared to the decorative and often more abstracted nudes of his friend Matisse, Marquet's are more grounded in observation, reminiscent perhaps of the unvarnished realism found in some works by Degas, though Marquet's handling is broader and more simplified. These works were considered somewhat bold for their time but are now recognized for their honesty and painterly quality.

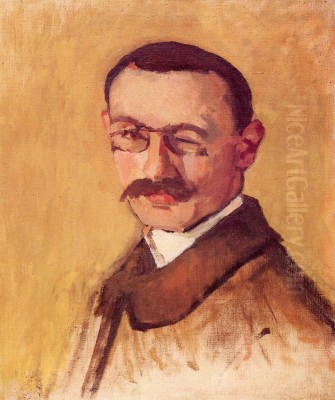

Marquet painted portraits less frequently, but those he did create reveal the same keen eye for observation and simplification. He aimed to capture the essential character of his sitters through posture and form rather than detailed psychological exploration. His portraits, like his landscapes, are marked by a sense of quiet presence and structural solidity.

A Quiet Life: Personality and Principles

Albert Marquet was known for his reserved and unassuming personality. He was described as quiet, modest, and somewhat introverted, a stark contrast to the more flamboyant personalities of some of his contemporaries like Maurice de Vlaminck. He preferred observation to discourse and found his primary means of expression through his painting.

His marriage to Marcelle Martin was crucial. She acted as his anchor and intermediary with the outside world, managing correspondence, exhibitions, and sales. This partnership allowed Marquet the peace and focus he needed for his dedicated, almost meditative, approach to painting.

His modesty extended to his view of official recognition. He consistently refused honors, including the prestigious Legion of Honour, and declined invitations to join established artistic institutions like the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He valued his independence and artistic integrity above public accolades. Despite his quiet nature, he possessed a subtle humor and a deep appreciation for the simple beauty of the world around him, qualities reflected in the calm and balance of his art.

Navigating Tumultuous Times

Marquet lived through two World Wars, which inevitably impacted his life and work. During World War I, his frail health exempted him from military service, allowing him to continue painting, though the period saw shifts in the art market and the dispersal of many artistic circles.

The outbreak of World War II led Marquet and his wife to leave Paris. They spent the war years, from 1940 to 1945, primarily in Algiers. While this move was prompted by the dangers and difficulties of life in occupied France, the familiar surroundings of North Africa provided a relatively stable environment where he could continue his work. Many paintings of the port and city of Algiers date from this period, imbued with the same quiet intensity as his earlier works. He returned to Paris soon after the liberation in 1945.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

After returning to France, Marquet resumed his life and work, dividing his time between Paris and La Frette-sur-Seine, just outside the city. He continued to paint his beloved river views and landscapes, his style remaining remarkably consistent in its focus on light, structure, and atmosphere.

His death in 1947, at the age of 72, came somewhat unexpectedly. Although he had suffered from health problems, including gallbladder issues which ultimately led to cancer, he had remained active. His passing marked the loss of a unique voice in French painting – an artist who navigated the currents of modernism while staying true to his own introspective vision.

Albert Marquet's legacy lies in his masterful synthesis of modern sensibilities – particularly the Fauvist liberation of color and form – with a deep respect for observation and traditional painterly values. He demonstrated that modernity did not necessarily require radical abstraction or emotional excess. His quiet, consistent dedication to capturing the essence of place through light and tone produced a body of work admired for its subtlety, harmony, and profound sense of peace. He remains a "painter's painter," appreciated for his technical skill and integrity, and his works continue to resonate with viewers drawn to their tranquil beauty.

Recognition: Exhibitions and Collections

Throughout his career and posthumously, Marquet's work has been featured in numerous exhibitions and acquired by major museums worldwide. While perhaps not achieving the same level of household fame as Matisse or Picasso, his reputation among curators, collectors, and fellow artists has remained high.

Significant exhibitions have periodically reassessed his contribution. A major retrospective, "Albert Marquet: Painter of Time," was held at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2016, showcasing over one hundred works and highlighting the consistency and independence of his vision across his career. Other notable shows include thematic exhibitions like "Itinéraires Maritimes" (Maritime Routes) at the Musée National de la Marine in Paris (2009), focusing on his seascapes, and exhibitions at institutions like the Muma - Le Havre Museum (2023) and historically important galleries like Wildenstein in New York.

His paintings are held in prestigious public collections across the globe, including the Musée d'Art Moderne and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, and many others in France and internationally. His inclusion in these collections underscores his importance within the narrative of 20th-century European art. Catalogues raisonnés and scholarly publications continue to explore his life and work, ensuring his contribution is not forgotten.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Albert Marquet occupies a unique and respected position in the history of modern art. Emerging alongside the Fauves, he shared their initial excitement for color but quickly channeled it into a more personal, contemplative style. He remained a lifelong friend of Henri Matisse, yet pursued a distinct artistic path characterized by subtlety, tonal harmony, and a profound connection to the observed world. His paintings of Paris, the ports of France and beyond, and the landscapes of North Africa are testaments to his mastery of light and atmosphere.

He was an artist of quiet consistency, returning again and again to his favored motifs, finding endless nuance in the play of light on water, the structure of a bridge, or the mood of a cityscape under changing skies. Uninterested in artistic manifestos or official honors, he dedicated himself to his craft with integrity and humility. Albert Marquet's enduring appeal lies in the serene beauty and understated power of his work, offering moments of calm reflection and a timeless appreciation for the visual world.