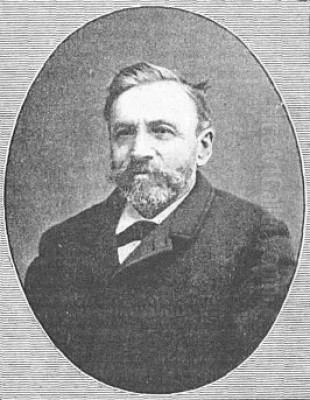

Stanislas Victor Edouard Lépine stands as a unique figure in nineteenth-century French art. Born in Caen, Normandy, on October 3, 1835, and passing away in Paris on September 28, 1892, Lépine dedicated his artistic life primarily to capturing the subtle beauties of Paris and its surrounding waterways, particularly the River Seine. Though often associated with the Impressionist movement, partly due to his participation in their first exhibition, his style retained a distinct character, bridging the gap between the Barbizon School's lyrical naturalism and the Impressionists' revolutionary approach to light and colour. He was a painter of quiet observation, delicate atmospheres, and enduring Parisian scenes, whose true recognition largely came posthumously.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Lépine hailed from Caen, a historic city in Normandy, born into a family with artisanal roots. His father was reportedly a cabinetmaker or furniture craftsman. This background perhaps instilled in him an appreciation for meticulous work, though his path would lead him away from traditional crafts towards the fine arts. Drawn to painting from a young age, Lépine appears to have been largely self-taught in his initial stages. Like many aspiring artists of his time, he honed his skills by studying and copying the Old Masters at the Louvre Museum in Paris after moving there around the age of 18 or 20. This practice provided a foundational understanding of composition, form, and technique.

A pivotal moment in Lépine's development came when he encountered Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875). By the early 1860s, Lépine had entered Corot's circle, and by 1866, he was officially listed in the Salon catalogue as Corot's student. Corot, a leading figure of the Barbizon School and a master of landscape painting renowned for his silvery light and poetic sensibility, exerted a profound influence on Lépine. While Lépine never simply imitated his master, Corot's emphasis on tonal harmony, subtle gradations of light, and capturing the overall mood of a scene deeply resonated with the younger artist's temperament.

Corot's guidance provided Lépine with a strong technical grounding and artistic direction. It encouraged his inclination towards landscape and helped him refine his ability to perceive and render the delicate nuances of light and atmosphere. This mentorship was crucial in shaping Lépine's artistic identity, placing him firmly within a lineage of French landscape painting while also allowing him the space to develop his own quiet, observational style. His early works already showed a preference for calm, often grey-toned views, setting the stage for his lifelong dedication to capturing the understated charm of his chosen subjects.

Influences Shaping a Vision

Beyond the foundational influence of Corot, Stanislas Lépine's artistic vision was shaped by several key figures and movements, most notably the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891). Jongkind, often considered a direct precursor to Impressionism, was admired by artists like Claude Monet for his ability to capture the fleeting effects of light and weather with spontaneous brushwork, particularly in his depictions of Dutch canals and French coastal scenes. Lépine absorbed Jongkind's sensitivity to atmospheric conditions and his skill in rendering water and sky, elements that would become central to Lépine's own work along the Seine.

The broader context of the Barbizon School also played a role. While Corot was his direct mentor, the general ethos of the Barbizon painters – artists like Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), and Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878) – emphasized direct observation of nature and a move away from idealized, historical landscapes. They sought truthfulness in their depictions of the French countryside. Lépine shared this commitment to observing the specific character of a place, though his focus shifted from rural forests and fields to the urban and suburban landscapes of Paris and its river.

Lépine synthesized these influences into a style uniquely his own. From Corot, he took the poetic sensibility and tonal harmony. From Jongkind, he learned to capture atmospheric effects and the fluidity of water. From the Barbizon School, he inherited a dedication to observing reality. However, Lépine filtered these influences through his own quiet, introspective personality, resulting in works that were less dramatic than Rousseau's, less socially focused than Millet's, and less overtly 'impressionistic' in technique than Monet would later become. His art found its niche in the subtle interplay of light, water, and the Parisian environment.

The Lépine Style: Subtlety and Atmosphere

Stanislas Lépine's artistic style is characterized by its subtlety, restraint, and profound sensitivity to atmosphere. He excelled at capturing the specific quality of light in Paris – often soft, diffused, and silvery, particularly in overcast conditions or during the transitional hours of dawn and dusk. His palette typically favoured muted tones, dominated by delicate greys, blues, ochres, and greens, applied with a refinement that avoided harsh contrasts. This tonal harmony contributes significantly to the serene, almost melancholic mood that pervades many of his paintings.

Unlike the core Impressionists such as Claude Monet (1840-1926) or Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), who often used broken brushwork and vibrant, unmixed colours to capture the immediacy of visual sensations, Lépine employed a more traditional technique, albeit with a modern sensibility. His brushwork was generally fine and controlled, building up surfaces with thin layers or glazes of paint. This method allowed him to achieve nuanced gradations of tone and a luminous quality, particularly in his skies and water reflections, without sacrificing the underlying structure of the scene.

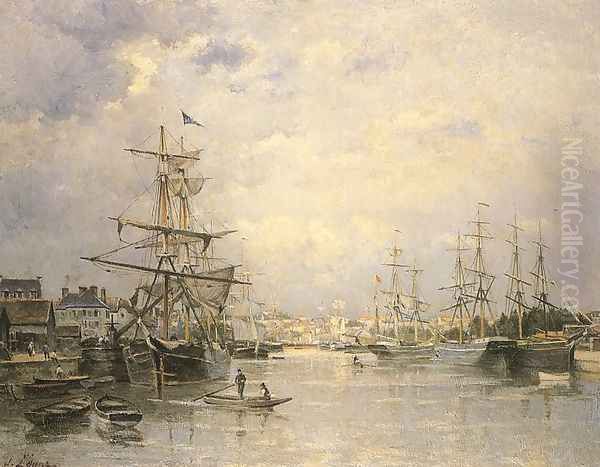

Water, especially the Seine, was a recurring motif, and Lépine masterfully rendered its reflective qualities and the gentle movement of its surface. He paid close attention to the interplay between the sky and the river, capturing how clouds and light conditions were mirrored in the water below. His compositions are often characterized by a sense of calm and stability, frequently employing horizontal lines – the riverbanks, bridges, distant horizons – to create a peaceful equilibrium. While he depicted the life of the river, such as barges and figures on the quays, they are typically integrated quietly into the overall atmospheric effect rather than serving as primary focal points. His focus remained steadfastly on the landscape and its ambient mood.

Paris and the Seine: An Enduring Subject

The city of Paris, and particularly the River Seine that flows through it, formed the heart of Stanislas Lépine's artistic output. He tirelessly explored the river's course through the city and its outskirts, capturing its varied moods and the structures that lined its banks. Bridges were a favourite subject – the Pont des Arts, the Pont Neuf, the Pont Marie – depicted not just as architectural elements but as integral parts of the Parisian riverscape, often silhouetted against luminous skies or reflected in the water's surface. His views frequently encompass the bustling quays, showing barges moored along the banks, small boats navigating the river, and the subtle signs of commerce and daily life.

Lépine also ventured into other areas of Paris, notably Montmartre. Before it became the crowded artistic hub of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Montmartre retained a more village-like atmosphere, and Lépine captured its quiet streets and windmills with the same sensitivity he applied to the Seine. His paintings offer glimpses of an older Paris, coexisting with the changes brought about by Baron Haussmann's massive urban renewal projects during the Second Empire. While not overtly documenting these transformations in the manner of some contemporaries, Lépine's work implicitly records the evolving cityscape.

His dedication to these specific Parisian locales connects him to other artists who found inspiration in the capital, such as the Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894), known for his depictions of Haussmannian Paris, albeit with a very different, more modern and sharply focused style. Lépine's approach, however, remained consistently focused on atmosphere and light rather than architectural precision or social commentary. He shared a love for water and skies with Eugène Boudin (1824-1898), another precursor of Impressionism famed for his Normandy beach scenes, though Lépine's focus was distinctly urban and riverine. Through his numerous canvases, Lépine created a poetic and enduring visual record of Paris and its vital artery, the Seine.

Navigating the Art World: Salons and Exhibitions

Lépine's career unfolded during a period of significant change in the Parisian art world, marked by the dominance of the official Salon and the rise of independent exhibition societies. He made his debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1859, the primary venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. He continued to exhibit there regularly throughout much of his career, submitting landscapes that adhered, at least superficially, to accepted norms while subtly showcasing his unique atmospheric sensibility. Success at the Salon was crucial for establishing a reputation, but it was often elusive, particularly for artists whose work deviated from academic standards.

A notable, yet perhaps atypical, moment in Lépine's career was his participation in the First Impressionist Exhibition held in 1874 at the former studio of the photographer Nadar. This landmark event brought together a diverse group of artists seeking an alternative to the Salon system, including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), and Renoir. Lépine's inclusion suggests connections and shared sympathies with this group, likely stemming from his friendships, his association with Corot (who was respected by many younger artists), and perhaps a shared interest in landscape and contemporary scenes.

However, Lépine's style remained distinct from the more radical techniques being explored by the core Impressionists. His work lacked the high-keyed palette and broken brushwork that characterized much of the art shown and which drew critical scorn. Consequently, his participation in the 1874 exhibition did not significantly boost his fame or align him firmly with the Impressionist label in the public eye. He remained a somewhat peripheral figure, respected by fellow artists but not achieving widespread recognition or commercial success through these independent ventures. He continued to navigate a path between the official Salon and the emerging avant-garde circles.

A Quiet Career: Struggles and Support

Despite his talent and dedication, Stanislas Lépine's career was marked by a persistent lack of widespread recognition and financial stability. He was described as having a modest, introverted, and retiring personality, seemingly ill-suited to the self-promotion often necessary for artistic success in the competitive Parisian art market. He preferred the quiet solitude of observation and painting to the bustling social life of cafés like the Café Guerbois or the Nouvelle Athènes, although he is known to have occasionally frequented places like the Bon Bock café, where he might have encountered fellow artists.

His financial struggles were significant. To support himself and his family (he remained unmarried but had three children), Lépine resorted to organizing public auctions of his own works between 1872 and 1886. These sales, sometimes facilitated by dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), who was a crucial supporter of the Impressionists, provided intermittent income but underscore the difficulty he faced in selling his work consistently through conventional channels. Durand-Ruel did handle some of Lépine's paintings, but perhaps not with the same vigour or success as he did for Monet or Renoir.

Lépine did find some crucial support from discerning collectors and patrons. An important connection was made through the colour merchant and artists' supplier Pierre-Firmin Martin, known as 'Père Martin', who also acted as an informal dealer. Martin introduced Lépine's work to influential collectors such as Count Armand Doria, a significant patron of Corot and later of Impressionists like Renoir and Sisley, and Nicholas-Auguste Hazard. These patrons acquired his works, providing vital encouragement and financial relief. Late in his career, Lépine received some official recognition when he was awarded a first-class medal at the Paris Salon of 1889, a welcome but perhaps overdue acknowledgment of his talent.

Key Works: Capturing Parisian Moments

While Stanislas Lépine produced a considerable body of work, certain paintings stand out as representative of his style and preferred subjects. His depictions of Parisian bridges are particularly notable. Pont des Arts, Paris, for instance, captures the delicate structure of the pedestrian bridge under a soft, atmospheric sky, with the Seine reflecting the subtle light. These bridge paintings often convey a sense of tranquility and timelessness, even amidst the urban setting. The focus is less on the engineering marvel and more on the bridge as a harmonious element within the riverscape.

Banks of the Seine (a title applied to numerous works) encapsulates his dedication to the river. These paintings typically show the quays, often with moored barges, perhaps a few figures strolling or working, under expansive skies. Lépine excelled at differentiating the textures of water, stone, and foliage, all unified by his characteristic handling of light and atmosphere. Whether depicting the river within the city center or further downstream towards the outskirts, these works consistently evoke a quiet, contemplative mood.

A work like Le Puits de Caen (The Well at Caen) demonstrates his connection to his Norman roots. While less common than his Parisian scenes, his paintings of Normandy, including views of Caen and coastal ports, share the same stylistic hallmarks: sensitive observation, subtle colour harmonies, and an emphasis on atmosphere. The Well at Caen likely depicts a specific, perhaps humble, location from his hometown, rendered with the same care and poetic feeling he brought to the grander vistas of the Seine. Collectively, these works showcase Lépine's consistent vision and his mastery in capturing the understated beauty of his chosen environments.

Connections and Contemporaries

Lépine's position in the art world placed him in contact with many significant figures, though his reserved nature meant his interactions were perhaps less documented than those of his more gregarious contemporaries. His relationship with Corot was paramount, defining his early training and influencing his lifelong aesthetic. The impact of Jongkind was also crucial, providing a model for capturing atmospheric effects with a degree of spontaneity that pointed towards Impressionism.

His participation in the 1874 Impressionist exhibition placed him alongside Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, Sisley, and Morisot, indicating at least a degree of shared purpose or mutual respect at that time. He maintained friendships with some, particularly Sisley, whose landscape work shares a certain gentle lyricism with Lépine's, though Sisley more fully embraced Impressionist techniques. He likely knew Eugène Boudin well, given their shared Norman origins (Boudin was from Honfleur) and mutual interest in skies and water, possibly encountering him in Paris or Normandy.

Lépine would have been aware of Édouard Manet (1832-1883), a central and often controversial figure in the modernization of painting, though evidence of a close personal friendship is scarce. They inhabited the same Parisian art world, and Manet's realism and focus on modern life paralleled, in different ways, Lépine's own commitment to contemporary scenes. Lépine's connection with dealers like Père Martin and Paul Durand-Ruel also linked him to the network supporting avant-garde art. His circle included patrons like Count Doria, who also collected works by Corot and Impressionists, highlighting the overlapping tastes among certain collectors who appreciated both traditional landscape values and emerging modern styles.

Final Years and Passing

The later years of Stanislas Lépine's life continued much as his career had progressed: marked by quiet dedication to his art but overshadowed by financial insecurity and a lack of broad public acclaim. Despite the first-class medal awarded at the 1889 Salon, this recognition did not translate into significant material success or widespread fame during his lifetime. He continued to paint his beloved views of the Seine and Paris, refining his subtle observations of light and atmosphere, seemingly undeterred by the changing tides of artistic fashion that saw Impressionism gain more traction, albeit slowly.

His financial situation remained precarious. Sources indicate that he lived in relative poverty towards the end of his life. This persistent struggle stands in contrast to the eventual appreciation and market value his works would achieve after his death. His commitment to his artistic vision, focused on the tranquil and poetic aspects of the Parisian landscape, never wavered, but it did not provide him with a comfortable living.

Stanislas Lépine died in Paris on September 28, 1892, just shy of his 57th birthday. The circumstances surrounding his death reflect his lifelong financial difficulties; it is reported that his friends had to collect funds to cover his funeral expenses. His passing marked the end of a career dedicated to capturing the quiet beauty of Paris with a unique blend of traditional sensitivity and modern observation. He left behind a significant body of work that awaited fuller appreciation from subsequent generations.

Legacy: A Reappraisal

In the decades following his death, Stanislas Lépine's reputation underwent a significant reappraisal. While overshadowed during his lifetime by both the established academic figures and the more revolutionary Impressionists, critics and art historians gradually came to recognize the unique quality and importance of his work. He became increasingly valued as a key transitional figure, an artist who absorbed the lessons of Corot and the Barbizon School while anticipating aspects of Impressionism through his sensitive handling of light and atmosphere and his dedication to contemporary urban landscapes.

His paintings, once difficult to sell, began to find favour with collectors and museums. Today, his works are held in prestigious collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Tate Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and numerous other institutions in France and abroad. This institutional recognition confirms his established place in the history of French landscape painting.

Art historians now appreciate Lépine for his consistent vision, his technical refinement, and the distinct poetic mood he captured in his views of Paris and the Seine. His subtle palette and focus on atmosphere offer a different perspective on the era, complementing the brighter, more dynamic works of the core Impressionists. His legacy is that of a dedicated, sensitive observer who chronicled the quiet charm of Paris with honesty and artistry. The existence of forgeries bearing his name, while problematic, also attests to the eventual market recognition and desirability his authentic works achieved posthumously.

Conclusion

Stanislas Lépine remains a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in French art history. A student of the great Corot, a contemporary and occasional exhibitor with the Impressionists, yet always slightly apart, he forged a distinct artistic path. His life was one of quiet dedication rather than flamboyant rebellion, his career marked by financial struggle rather than widespread acclaim. Yet, through his persistent observation and refined technique, he created an enduring body of work centered on the subtle beauties of Paris, particularly the Seine.

His paintings offer a tranquil, atmospheric counterpoint to the dynamism often associated with depictions of modern Paris. With a palette favouring silvery greys and muted tones, and a brushstroke that built form through subtle layering, Lépine captured the nuances of light on water, the silhouettes of bridges against hazy skies, and the quiet life along the riverbanks. He stands as a crucial link between the Barbizon tradition of lyrical landscape and the Impressionist exploration of light and contemporary life. Though his recognition was largely posthumous, Stanislas Lépine's sensitive and poetic vision has secured him a lasting place as a master of the Parisian landscape.