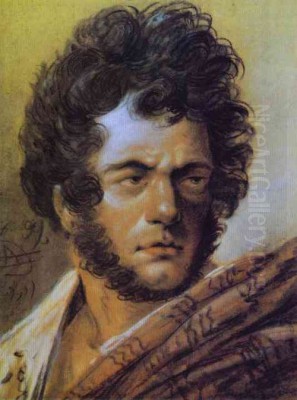

Aleksander Orlowski, a name that resonates with the vibrant artistic currents of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, stands as a significant figure in both Polish and Russian art history. Born Aleksander Orłowski on March 9, 1777, in Warsaw, Poland, and passing away on March 13, 1832, in Saint Petersburg, Russia, his life and career traversed a period of immense political upheaval and cultural transformation. A painter, draughtsman, and a pioneer of lithography in Russia, Orlowski's oeuvre is characterized by its Romantic spirit, keen observation of everyday life, dramatic historical and battle scenes, and incisive caricatures. His dual heritage and artistic journey offer a fascinating lens through which to view the interconnectedness of European art movements and the development of national artistic identities.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Warsaw

Aleksander Orlowski's origins were modest. His father was an innkeeper in the town of Siedlce. However, his artistic talents did not go unnoticed. A pivotal figure in his early life was Princess Izabela Czartoryska, a prominent Polish aristocrat and a renowned patron of the arts and sciences. Recognizing the young Orlowski's potential, Princess Czartoryska took him under her wing, ensuring he received a formal artistic education. This patronage was crucial, opening doors that would otherwise have remained closed to someone of his background.

In Warsaw, Orlowski was apprenticed to two distinguished artists in the employ of the Czartoryski family: Jean-Pierre Norblin de la Gourdaine and Marcello Bacciarelli. Norblin, a French painter who had settled in Poland, was a versatile artist known for his genre scenes, portraits, and depictions of contemporary Polish historical events, often rendered with a realistic and lively touch. His influence on Orlowski can be seen in the latter's interest in everyday subjects and dynamic compositions. Bacciarelli, an Italian painter, served as the court painter to King Stanisław August Poniatowski and was a leading figure of Neoclassicism in Poland, though his portraiture also contained elements of late Baroque sensibility. From Bacciarelli, Orlowski would have absorbed the more formal aspects of painting, particularly in portraiture.

Orlowski began his studies and artistic work in Warsaw around 1793. During these formative years, he developed a style marked by strong expressiveness and often imbued with a sense of humor. An early example of this is his "Tavern Scene," which showcases his ability to capture the vivacity and character of ordinary people. This period in Warsaw, lasting nearly two decades before his eventual move to Russia, laid the foundation for his artistic identity, blending Polish cultural influences with the broader European artistic trends introduced by his mentors.

The Kościuszko Uprising and Its Aftermath

Orlowski's early adulthood coincided with a tumultuous period in Polish history. In 1794 (the provided text mentions 1793 for his joining, the Uprising itself is primarily 1794), he actively participated in the Kościuszko Uprising, a Polish national insurrection against Russian and Prussian control, led by Tadeusz Kościuszko. Orlowski served in the Polish army, and his experiences during this patriotic struggle profoundly impacted him and his art. He was not merely a soldier but also an artist-chronicler, creating sketches and drawings that documented the events and figures of the uprising. These works often carried strong patriotic and liberationist themes, such as his notable piece, "March of Kościuszko's Troops."

During the fighting, Orlowski was wounded. After his injury, he returned to Warsaw, where his artistic pursuits continued, reportedly with financial support from Prince Józef Poniatowski, a key military figure and nephew of the last Polish king. The defeat of the Kościuszko Uprising was a national tragedy for Poland, leading to the Third Partition and the erasure of Poland from the map of Europe for over a century. For Orlowski, this period was undoubtedly one of intense emotion and perhaps disillusionment. There's a brief mention of him joining a traveling circus troupe after the uprising's failure, a colorful interlude that speaks to his adventurous spirit, before his teacher Norblin persuaded him to return fully to his artistic endeavors.

Transition to Saint Petersburg: A New Chapter

In 1802, a significant shift occurred in Orlowski's life and career: he moved to Saint Petersburg, the opulent capital of the Russian Empire. This move marked the beginning of the "Russian" phase of his artistic journey. In Russia, his talents soon found recognition and, crucially, patronage. He came under the protection of Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich, the brother of Tsar Alexander I. This imperial connection was invaluable, providing Orlowski with stability and opportunities.

His skills were quickly acknowledged by the artistic establishment. In 1809, he was granted the title of Academician by the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, a prestigious honor. Subsequently, he was appointed as a court painter. This position solidified his status within the Russian art world and ensured a steady stream of commissions. He would spend the remainder of his life in Saint Petersburg, becoming an integral part of its cultural fabric while retaining his Polish identity. His studio became a meeting place for artists and writers, including, it is said, the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin and the fabulist Ivan Krylov, indicating his integration into the Russian intellectual elite.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Aleksander Orlowski's art is a compelling fusion of Romanticism and Realism. The Romantic sensibility is evident in his dramatic compositions, his fascination with the exotic (such as Cossacks, Tatars, and Caucasian peoples), his depictions of powerful emotions, and his interest in historical and heroic subjects. His battle scenes, often featuring dynamic portrayals of horses and soldiers, pulse with energy and movement, reminiscent of the work of French Romantic painters like Théodore Géricault and Horace Vernet, whose works he may have encountered or been influenced by through prints or study.

Simultaneously, a strong current of Realism runs through his work, particularly in his genre scenes and caricatures. He possessed a keen eye for the details of everyday life and a remarkable ability to capture the character and psychology of his subjects. His depictions of Russian peasants, merchants, soldiers, and street vendors are rendered with an authenticity that brings them to life. This focus on the lower strata of society, often portrayed with empathy and sometimes humor, aligns him with a broader European trend towards genre painting that found earlier expression in the works of Dutch masters like Adriaen Brouwer or David Teniers the Younger, whose influence might have been transmitted via Norblin.

Orlowski was a master of the quick sketch, able to capture fleeting moments and expressions with remarkable facility. His drawings and watercolors often display bold, energetic lines and an almost impressionistic handling of form and color. This spontaneity was particularly effective in his caricatures, where he skillfully exaggerated features to highlight personality traits or satirize social types. His humor was a defining characteristic, evident not only in his caricatures but also in many of his genre scenes.

Pioneering Lithography in Russia

One of Orlowski's most significant contributions to Russian art was his pioneering work in lithography. Invented by Alois Senefelder in Germany in 1796, lithography was a relatively new printing technique that allowed for greater freedom and subtlety of expression than earlier methods like engraving or etching. Orlowski was among the first artists in Russia to embrace this new medium, beginning his experiments around 1816.

He quickly mastered lithography, producing a considerable body of work that included single sheets and thematic albums. These lithographs covered a wide range of subjects, from military scenes and depictions of Russian folk life to portraits and caricatures. His "Collection of Russian Scenes" (1826) and individual prints like "Ural Tartar Camp" (1809, though this date might refer to an earlier drawing or painting version, with the lithograph produced later) were highly popular and helped to popularize the medium in Russia. He also created a series of 40 lithographs for Gaspar Drouville's book "Voyage en Perse," showcasing his versatility.

Orlowski's lithographs were admired for their technical skill and artistic merit. He understood how to exploit the medium's potential for rich tonal variations and expressive lines, creating prints that often had the immediacy of drawings. His work in lithography not only expanded his own artistic reach but also paved the way for other Russian artists to explore this versatile printmaking technique. His efforts were instrumental in establishing lithography as an important artistic medium in 19th-century Russia, influencing later graphic artists and caricaturists like Ivan Terebenyov, who also gained fame for his satirical prints, especially during the Napoleonic Wars.

Notable Works and Series

Throughout his career, Aleksander Orlowski produced a diverse and extensive body of work. Among his historically significant pieces is the "Battle of Racławice" (1802), depicting a key victory for Polish forces during the Kościuszko Uprising. This work, likely painted before his move to Russia or shortly thereafter, reflects his patriotic engagement and his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions. Another work reflecting his Polish roots and the Uprising's themes is "Polish Insurgent Forester at Night."

His Russian period saw a proliferation of works capturing the essence of his new environment. His sketches and watercolors of Russian rural life are invaluable documents of the era, filled with vivid character studies. The "Ural Tartar Camp" (1809) exemplifies his interest in the diverse peoples of the Russian Empire, a common theme in Romantic art's fascination with the "exotic." His "Seascape" (1813) demonstrates his capabilities in landscape painting, capturing the mood and atmosphere of the sea.

Orlowski was also a prolific portraitist, painting Polish nobles, members of the Russian imperial family, and cultural figures. His portrait of the "Italian composer Muzio Clementi" is one such example. However, it was perhaps his caricatures that brought him particular contemporary fame and have had a lasting impact. Series like the "Katya" caricatures and individual satirical portraits such as "Polish Governor" and "Brigaglov" (likely a caricature of I.S. Bryzgalov) showcased his sharp wit and his ability to lampoon human foibles and societal figures. These works place him as a foundational figure in the Russian school of caricature.

In 1819, he was attached to the General Staff of the Russian army, tasked with designing new military uniforms. This role naturally led to numerous drawings and paintings of military subjects, further cementing his reputation as a skilled depictor of soldiers and battle scenes. His works often featured Cossacks, cavalry, and scenes from military life, rendered with his characteristic dynamism. While a "War and Peace" series is mentioned, this likely refers to a collection of works depicting the Napoleonic Wars (known in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812) rather than an illustration of Leo Tolstoy's later novel. These works would have captured the drama and heroism of that conflict.

Relationships with Contemporaries and Influences

Orlowski's artistic development was shaped by his teachers, Jean-Pierre Norblin and Marcello Bacciarelli, who provided him with a solid grounding in drawing, painting, and composition. Norblin, in particular, with his Rococo-influenced realism and interest in genre scenes, seems to have had a lasting impact on Orlowski's thematic choices and lively style.

In Saint Petersburg, Orlowski moved in prominent artistic and intellectual circles. His friendships with figures like Alexander Pushkin and Ivan Krylov suggest a shared cultural milieu. Pushkin, the preeminent Russian Romantic poet, and Orlowski, a leading Romantic visual artist, likely found common ground in their creative pursuits and their engagement with Russian life and character. Orlowski's vivid portrayals of Russian types may well have resonated with Pushkin's own literary creations. He was also acquainted with Pyotr Vasilyevich Denisov, another figure in the Russian cultural scene.

His work shows affinities with European Romantic artists. The dynamism and equine mastery in his military scenes can be compared to those of Théodore Géricault (e.g., "The Charging Chasseur") and Horace Vernet, both celebrated for their battle paintings. While direct contact might have been limited, the circulation of prints would have made their work known. Some scholars also note a certain reliance on 17th-century Dutch genre painting conventions, possibly inherited from Norblin or through independent study, evident in his tavern scenes and depictions of peasant life. The character studies and dramatic lighting in some of his works might even distantly echo the spirit of Rembrandt. For earlier graphic influences, one might consider the impact of artists like Jacques Callot, known for his detailed etchings of military life and social types.

Among his Russian artistic contemporaries, Orest Kiprensky was a leading Romantic portraitist, and Karl Bryullov would later achieve immense fame with grand historical paintings like "The Last Day of Pompeii." While Orlowski's style was distinct, he was part of this broader Romantic movement in Russian art. Alexey Venetsianov, another contemporary, focused on idealized scenes of Russian peasant life, offering a different, more poetic perspective compared to Orlowski's often more robust and humorous depictions.

In the Polish context, artists like Piotr Michałowski, slightly younger than Orlowski, also became renowned for his Romantic paintings, especially of horses and battle scenes, sharing some thematic interests. January Suchodolski was another Polish painter known for his historical and military subjects. Franciszek Smuglewicz, active in an earlier generation, contributed to historical painting in Poland with a Neoclassical bent that sometimes veered towards Romantic sentiment.

Personality and Social Standing

Aleksander Orlowski was reportedly a man of considerable charm and wit. His humor, so evident in his art, was also a feature of his personality. He was known for his sociability and was a popular figure in Saint Petersburg's high society. His studio was a lively hub, attracting artists, writers, and members of the aristocracy.

However, contemporary accounts also suggest a more complex personality. He was said to be somewhat conceited and highly sensitive to criticism. These traits, combined with a reported streak of laziness or inconsistency in application, may have, according to some critics, prevented him from achieving even greater artistic heights or a more polished finish in some of his works. Despite these perceived flaws, his talent was widely recognized, and he enjoyed considerable success and official patronage throughout his Russian career.

His position as a Polish artist thriving in the Russian capital during a period of Polish subjugation was inherently complex. While he was celebrated in Russia, some Polish commentators later criticized him, suggesting that his long residence in Saint Petersburg led to an estrangement from his homeland or even a betrayal of Polish national sentiment. Such criticisms, however, must be viewed in the context of the intense nationalism of the 19th century. Orlowski's art, even in its Russian phase, often retained a distinct character that spoke to his Polish origins and early training.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Aleksander Orlowski left an indelible mark on both Polish and Russian art. In Poland, he is remembered as one of the notable artists of the turn of the 19th century, a participant in a pivotal national uprising, and a talent whose career blossomed, albeit largely outside of his partitioned homeland. His early works captured the spirit of Polish life and history.

In Russia, his legacy is perhaps even more pronounced. He is celebrated as a key figure of the Romantic era and, crucially, as a pioneer of lithography. His introduction and popularization of this medium had a lasting impact on Russian graphic arts. Furthermore, his incisive and humorous caricatures are considered foundational to the development of Russian satirical art. Artists like Ivan Terebenyov and later figures in Russian caricature owed a debt to Orlowski's pioneering work.

His genre scenes provided a vibrant, unvarnished look at the diverse social fabric of the Russian Empire, from its peasants and merchants to its soldiers and ethnic minorities. These works contributed to the growing interest in national character and everyday life that characterized much of 19th-century Russian art, a path later explored by artists like Vasily Perov and the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, though their approach was often more overtly critical and socially conscious.

Despite criticisms regarding technical imperfections or an alleged lack of consistent effort, the sheer vitality, expressiveness, and historical importance of Orlowski's work are undeniable. His paintings, drawings, and prints are housed in major museums in Poland, Russia, and beyond, attesting to his enduring appeal. He successfully navigated the complex cultural and political currents of his time, creating a body of work that serves as a bridge between Polish and Russian artistic traditions.

Conclusion

Aleksander Orlowski was an artist of remarkable versatility and energy. From his early training in Warsaw under the patronage of Princess Czartoryska and his involvement in the Kościuszko Uprising, to his successful career as a court painter and lithography pioneer in Saint Petersburg, his life was one of constant artistic exploration. He masterfully blended Romantic drama with realistic observation, capturing the spirit of his age with a unique blend of dynamism, humor, and empathy. His contributions to genre painting, military art, portraiture, and especially caricature and lithography, secure his place as an important and influential figure in the art history of both Poland and Russia, a testament to his talent and his ability to transcend national boundaries while reflecting the rich cultural tapestry of his era.