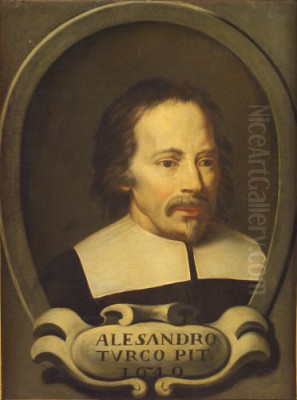

Alessandro Turchi, an artist whose life and career bridged the late 16th and mid-17th centuries, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of Italian Early Baroque painting. Born in Verona in 1578 and passing away in Rome in 1649, Turchi, also known by the epithet Alessandro Veronese or the intriguing nickname "L'Orbetto," carved out a distinctive artistic identity. His work is characterized by a sophisticated fusion of the rich colorism of his native Veneto, the dramatic intensity of Caravaggesque naturalism, and the ordered grace of Roman classicism. This synthesis resulted in paintings that are both emotionally resonant and visually refined, securing him a notable place among his contemporaries and a lasting legacy in European art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Verona

Alessandro Turchi's artistic journey began in Verona, a city with a proud artistic heritage, having nurtured talents like Paolo Caliari, famously known as Veronese, and Paolo Farinati. Turchi's initial training was under Felice Brusasorci (also spelled Brusasorzi), a prominent local painter. Under Brusasorci's tutelage, Turchi absorbed the fundamentals of the Veronese school, which emphasized rich color, dynamic composition, and often, a certain lyrical quality. He demonstrated considerable talent early on, and by 1603, he was registered as an independent painter in Verona, a testament to his burgeoning skills and ambition.

The death of Felice Brusasorci around 1605 marked a pivotal moment for the young Turchi. He, along with fellow pupil Pasquale Ottino and another contemporary Veronese painter, Marcantonio Bassetti, undertook the responsibility of completing their master's unfinished works. This collaborative effort not only honored their teacher but also provided invaluable experience in handling large-scale commissions and harmonizing different artistic hands. During these formative years in Verona, Turchi began to establish his reputation, securing commissions for altarpieces and other religious works for local churches and influential patrons, including the city's goldsmiths' guild. Notable works from this Veronese period include an Assumption of the Virgin (1610) and a Madonna and Saints (1612) for the church of San Luca, though the latter is reportedly lost. These early pieces likely reflected the prevailing late Mannerist and early Baroque trends of Verona, infused with his developing personal style.

The Lure of Rome and Artistic Maturation

Around 1614 or 1615, Alessandro Turchi made the significant decision to relocate to Rome. The Eternal City was, at this time, the undisputed epicenter of the art world, a magnet for ambitious artists from across Italy and Europe. It was a place of intense artistic ferment, dominated by the revolutionary naturalism of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio and the burgeoning classicism championed by Annibale Carracci and his followers. For Turchi, Rome offered unparalleled opportunities for patronage, learning, and artistic exchange.

Soon after his arrival, Turchi found prestigious employment, contributing to the decoration of the Sala Regia in the Quirinal Palace. Here, he worked alongside other notable artists, including Giovanni Lanfranco and Carlo Saraceni, on projects such as the Gathering of Manna. Saraceni, a Venetian who had also fallen under Caravaggio's spell, and Lanfranco, a key figure in the development of High Baroque ceiling painting, would have provided stimulating company. This commission placed Turchi at the heart of papal patronage and exposed him directly to the major artistic currents shaping Roman art.

It was in Rome that Turchi's style underwent a profound evolution. While retaining the sensitivity to color ingrained from his Veronese training, he became increasingly influenced by the dramatic use of light and shadow – chiaroscuro and tenebrism – pioneered by Caravaggio. Unlike some of the more rugged Caravaggisti, Turchi's interpretation was often more tempered, characterized by a softer modeling and a more refined, almost polished, finish. He masterfully blended this Caravaggesque drama with the compositional clarity and idealized forms associated with the classical tradition, which was being reinvigorated by artists like Guido Reni and Domenichino.

Key Patrons and Prestigious Commissions

Turchi's talent did not go unnoticed in the competitive Roman art scene. He attracted the attention of influential patrons, most notably Cardinal Scipione Borghese, one of the most avid and discerning art collectors of his era. For Cardinal Borghese, Turchi executed several significant works, which are now housed in the Galleria Borghese. These include paintings like Christ Bound and The Lamentation over the Dead Christ. These commissions for such a high-profile patron significantly enhanced Turchi's reputation and visibility.

His patronage extended to other prominent Roman families, such as the Giusti and, according to some sources, the Borgia family. He also continued to receive commissions for altarpieces and devotional paintings for various churches. His ability to create works that were both dramatically engaging and elegantly composed made him a sought-after artist for both public and private collections. His paintings on stone, particularly slate, became a hallmark, with the dark, smooth surface enhancing the luminosity of his figures and the depth of his shadows.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Alessandro Turchi's mature artistic style is a compelling amalgamation of diverse yet complementary influences. His Veronese origins endowed him with a natural affinity for rich, harmonious color, reminiscent of the great Venetian masters like Titian, Tintoretto, and his namesake, Paolo Veronese. This Venetian sensibility for color remained a constant in his work, even as he adapted to the artistic environment of Rome.

The impact of Caravaggio on Turchi was transformative. He embraced the use of strong chiaroscuro to create dramatic effects, heighten emotional intensity, and give his figures a tangible, three-dimensional presence. Works like his Death of Cleopatra (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) or Christ Crucified (Louvre, Paris) showcase this effective use of light and shadow to underscore the narrative's poignancy. However, Turchi's Caravaggism was often more lyrical and less stark than that of artists like Jusepe de Ribera or some of the Northern Caravaggisti. He favored a more diffused light and smoother transitions between light and dark, resulting in a "softened" Caravaggesque manner.

Simultaneously, Turchi was receptive to the classical ideals that were gaining prominence in Rome, largely through the influence of the Bolognese school, particularly Annibale Carracci and his pupils Domenichino and Guido Reni. This classical strain is evident in the balanced compositions, the idealized yet naturalistic rendering of figures, and the overall sense of order and decorum in many of his paintings. He managed to integrate these classical elements without sacrificing the emotional depth or visual richness of his work. This fusion created a style that was both expressive and elegant, appealing to the sophisticated tastes of his Roman patrons.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Throughout his career, Turchi produced a considerable body of work, primarily focusing on religious and mythological subjects. His Flight into Egypt, for instance, often depicts the Holy Family with a tender intimacy, the figures illuminated against a dark, atmospheric landscape, showcasing his skill in rendering emotion and his characteristic nocturnal or crepuscular settings. The Madonna and Child was a recurring theme, and one such painting, tragically, has a more modern history: a version was looted by the Nazis during World War II, later discovered in Japan, and eventually returned to Poland, highlighting the enduring value and complex fate of artworks through history.

His Christ in the Sepulchre or The Lamentation are powerful examples of his ability to convey profound grief and piety. In these works, the figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and attendant saints or angels are often rendered with a sculptural solidity, their sorrow amplified by the dramatic interplay of light and shadow. The use of dark supports, such as slate or marble, in some of these pieces, allowed Turchi to achieve exceptionally deep blacks, making the illuminated figures emerge with striking intensity.

Mythological scenes, such as The Judgment of Paris, allowed him to explore classical narratives and the idealized human form. His depiction of Cleopatra, particularly her death, was a popular theme in Baroque art, offering opportunities for dramatic pathos and the portrayal of exotic beauty. Turchi's versions typically combine a sense of tragedy with a refined aesthetic. Another notable work is Saint Peter Heals Saint Agatha in Her Prison, located in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg, which demonstrates his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with clarity and emotional force.

The Enigmatic Nickname "L'Orbetto"

Alessandro Turchi was widely known by the nickname "L'Orbetto," which translates to "the little blind one" or "the blind boy." The precise origins of this moniker are subject to some debate among art historians. One common theory suggests it stemmed from his father, who was reportedly blind and may have been a beggar. If true, this would add a layer of poignancy to Turchi's rise to prominence.

Another interpretation, particularly popular from the latter half of the 17th century, links the nickname to Turchi's own artistic practices. It has been speculated that "L'Orbetto" might have alluded to his meticulous, perhaps even painstakingly slow, method of painting, or more compellingly, to his innovative use of unconventional painting supports. Turchi was renowned for painting on dark materials such as slate, black marble, and copper. These non-absorbent, smooth surfaces allowed for a jewel-like finish and enhanced the effects of his chiaroscuro, making the figures appear to glow from within the surrounding darkness. This distinctive technical preference could have contributed to a nickname that, while seemingly referencing sight, might have paradoxically pointed to his unique vision for creating luminosity out of darkness.

Prominence in the Accademia di San Luca

Turchi's success in Rome was formally recognized by his peers. He became a member of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, the official artists' academy in Rome. This institution played a crucial role in the artistic life of the city, regulating the profession, providing training, and fostering artistic discourse. Membership was a mark of distinction.

His standing within the Accademia grew over the years, culminating in his election as Principe (Director or President) of the institution in 1637. This was a significant honor, placing him at the helm of Rome's leading artistic body and underscoring his respected position within the Roman art establishment. Serving as Principe involved administrative duties, representing the Academy, and upholding its standards. His tenure in this role would have brought him into close contact with other leading artists of the day, such as Pietro da Cortona, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Andrea Sacchi, and Nicolas Poussin, all of whom were active in Rome and shaped the diverse landscape of Baroque art.

Later Career, Death, and Lasting Legacy

Alessandro Turchi remained active in Rome for the rest of his life, continuing to produce works for churches and private collectors. He successfully navigated the shifting artistic tastes of the period, maintaining a consistent quality and a distinctive style that, while evolving, remained true to his core artistic principles. He passed away in Rome in 1649.

In the centuries following his death, Turchi's reputation endured, particularly among collectors. His paintings were sought after, especially in France and England, where his refined style and dramatic intensity found appreciative audiences. Today, his works are held in major museums and collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the Galleria Borghese in Rome, the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery in London, among many others.

Alessandro Turchi's contribution to Early Baroque art lies in his skillful synthesis of diverse artistic traditions. He was not a radical innovator in the mold of Caravaggio, nor a grand decorator like Pietro da Cortona. Instead, he carved out a niche for himself by creating works of remarkable sensitivity, technical finesse, and emotional depth. His ability to imbue religious and mythological scenes with a quiet yet powerful drama, his mastery of light and color, and his distinctive use of materials like slate ensure his place as an important and engaging master of the Italian Baroque. His career demonstrates the rich cross-currents of artistic influence in the 17th century and the enduring appeal of art that speaks with both elegance and conviction.