Alexander Fraser, often referred to as Alexander Fraser the Elder to distinguish him from his artist son, Alexander Fraser the Younger (1827-1899), was a significant figure in early to mid-19th century Scottish art. Born in the historic city of Edinburgh on April 7, 1786, and passing away in London on February 15, 1865, Fraser's career spanned a period of dynamic change and development in British art. He is primarily celebrated for his detailed and engaging genre scenes, his carefully observed still-life passages, and his contributions to landscape painting, all of which captured the character and spirit of Scottish life and its environs. His work forms an important bridge between the earlier traditions of Scottish painting and the burgeoning national school that gained prominence throughout the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Edinburgh

Fraser's artistic journey began in his native Edinburgh, a city that, by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was a vibrant hub of intellectual and cultural activity, often dubbed the "Athens of the North." He enrolled at the Trustees' Academy, officially the Board of Trustees for Fisheries, Manufactures and Improvements in Scotland's School of Design. This institution was pivotal in the development of Scottish art, providing foundational training for many of the nation's most distinguished artists.

At the Trustees' Academy, Fraser was a contemporary of several individuals who would also achieve considerable fame. Most notably, he studied alongside David Wilkie (1785-1841), who would become one of Britain's most celebrated painters, renowned for his meticulously detailed and narratively rich genre scenes. Another prominent classmate was John Watson Gordon (1788-1864), who later became Sir John Watson Gordon and President of the Royal Scottish Academy, achieving eminence as a portrait painter. The environment at the Academy, likely under the tutelage of figures such as the landscape painter Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840), who taught there for a period, or his successor John Graham (1754-1817), would have emphasized drawing from casts, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters, providing Fraser with a solid technical grounding.

Fraser's early works began to appear in exhibitions, and he first showed at the prestigious Royal Academy in London in 1810. This initial foray into the London art scene was a significant step, indicating his ambition and the development of his skills to a level worthy of national attention. His early output likely reflected the prevailing tastes and the training he received, possibly including landscapes and tentative genre pieces.

The London Years and the Crucial Association with David Wilkie

In 1813, seeking broader opportunities and a more competitive artistic environment, Alexander Fraser made the pivotal decision to move to London. This move was undoubtedly influenced by the path already trodden by his slightly older contemporary, David Wilkie, who had relocated to London in 1805 and was rapidly achieving phenomenal success. Soon after arriving in London, Fraser became an assistant to Wilkie. This professional relationship was to last for nearly two decades and was profoundly influential on Fraser's artistic development and career.

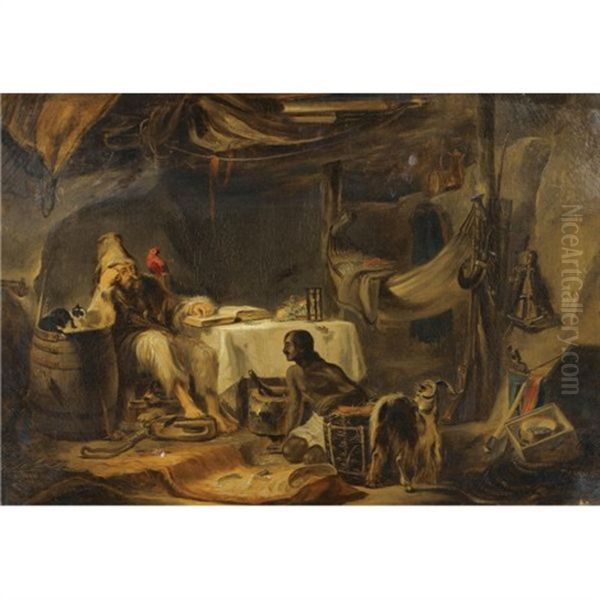

Working in Wilkie's studio, Fraser's primary responsibilities involved painting in the details, accessories, and still-life elements within Wilkie's increasingly complex and popular compositions. Wilkie's own style was heavily inspired by 17th-century Dutch and Flemish genre painters like David Teniers the Younger and Adriaen van Ostade, characterized by intricate detail, subtle humour, and keen observation of everyday life. By meticulously rendering these components for Wilkie, Fraser honed his own skills in precision, texture, and the arrangement of objects, which became hallmarks of his independent work, particularly his still-life subjects.

This period was not one of mere servitude; it was an immersive, high-level apprenticeship. Fraser was intimately involved in the creation of some of the most famous British paintings of the era, absorbing Wilkie's compositional strategies, his approach to narrative, and his meticulous technique. While this association might have somewhat overshadowed Fraser's independent identity during these years, it provided him with invaluable experience, financial stability, and a close connection to the heart of the British art world. The skills he refined in depicting inanimate objects, from humble household items to more elaborate furnishings, would serve him well throughout his career.

Independent Career and Artistic Style

Despite his long and close working relationship with David Wilkie, Alexander Fraser the Elder also pursued his own independent artistic career, producing a significant body of work that showcased his individual talents and thematic interests. His style, while inevitably bearing some resemblance to Wilkie's due to their close association and shared admiration for Dutch Golden Age masters, developed its own distinct characteristics.

Fraser became particularly known for his genre scenes, often depicting Scottish rural life, domestic interiors, and anecdotal incidents with a gentle humour and keen eye for character. These paintings were typically smaller in scale than Wilkie's grander narratives but were no less carefully composed and executed. He had a talent for capturing expressive figures and creating a sense of lived-in reality within his settings. His works often told a story, inviting viewers to engage with the depicted characters and their activities.

His landscapes, though perhaps less numerous than his genre pieces, demonstrated a sensitivity to the Scottish scenery. He also excelled in pure still-life painting, where his meticulous attention to detail and ability to render textures – the gleam of metal, the roughness of earthenware, the softness of fruit – truly shone. Art historians note that while his handling could sometimes be perceived as slightly harder or less fluid than Wilkie's, his draftsmanship was strong, and his colouring was often rich and harmonious. He was adept at conveying the material quality of objects, a skill undoubtedly perfected during his years assisting Wilkie.

Fraser was a regular exhibitor at major London venues such as the Royal Academy and the British Institution, and also in Scotland, particularly at the Royal Scottish Academy, of which he became an Associate (ARSA) in 1840 and a full Academician (RSA) in 1842. This recognition from his Scottish peers underscored his standing within the national school.

Key Themes and Subjects in Fraser's Oeuvre

Alexander Fraser the Elder's paintings often revolved around themes that were popular in the early 19th century, particularly those celebrating domesticity, rural simplicity, and everyday human interactions. His Scottish heritage frequently informed his choice of subjects, and he contributed to the romanticized yet affectionate portrayal of Scottish life that was prevalent in art and literature of the period, partly fueled by the writings of Sir Walter Scott.

Many of his genre scenes are set in humble cottage interiors or village environments. He depicted cobblers at work, families gathered around a hearth, children at play, and moments of quiet contemplation or lively social interaction. These scenes were often imbued with a narrative quality, sometimes humorous, sometimes poignant, but always relatable. The inclusion of carefully rendered animals, such as dogs and cats, added to the domestic charm of his compositions.

Still-life elements were not just accessories in his genre paintings but often formed subjects in their own right or were given significant prominence. He might paint a collection of game, a tumble of vegetables, or an arrangement of kitchen utensils with the same care and attention he devoted to his figures. This reflects the broader appreciation for still-life painting that had roots in Dutch art and was finding renewed interest.

His landscapes often depicted identifiable Scottish locations or more generalized scenes of the countryside, sometimes with figures engaged in rural labor or leisure, linking the landscape to human activity. While not as focused on the sublime as some of his contemporaries, his landscapes conveyed a genuine appreciation for the character of the land.

Notable Works and Artistic Achievements

Identifying a definitive list of "masterpieces" for an artist like Fraser, whose work was consistently competent and appealing rather than groundbreaking in a revolutionary sense, can be challenging. However, several paintings are frequently cited as representative of his skill and thematic concerns.

Among his well-regarded works are:

Tapping the Ale Cask (also known as The Interior of a Cobbler's Shop or similar titles for related subjects): This painting, or variations on the theme, showcases his ability to create a lively interior scene, rich in anecdotal detail and character study. The depiction of the cobbler, his tools, and the eager anticipation of the ale would have resonated with contemporary audiences.

The Village Painter: This subject allowed Fraser to explore the world of the artist, perhaps with a degree of self-reflection or gentle satire, a theme also explored by contemporaries.

The Blackbird and his Tutor: Such a title suggests a charming, possibly allegorical scene involving animals or children, typical of the era's taste for sentimental or instructive narratives.

The Glass of Ale: This title points towards his skill in still life and the depiction of tavern scenes or moments of refreshment, common in the Dutch tradition he admired.

Alarms of War: This suggests a more dramatic narrative, perhaps a domestic scene interrupted by news from a conflict, allowing for the depiction of heightened emotion and a story unfolding.

Paintings of Rosslyn Chapel: Fraser is known to have painted the intricately carved interior of Rosslyn Chapel, near Edinburgh, on multiple occasions. This historic and architecturally rich site was a popular subject for artists, offering a chance to display technical skill in rendering complex details and atmospheric effects. These works would have appealed to the antiquarian and romantic interests of the time.

While the provided information mentions a work titled Robinson Crusoe, it's important to clarify. Daniel Defoe's novel Robinson Crusoe was published in 1719. Fraser, living much later, might have painted a scene inspired by the novel, as literary subjects were common. However, without a specific, dated painting by Fraser with this title readily identifiable in major collections or art historical literature, it's more likely a thematic interest of the period rather than a signature work of his. Similarly, Last Moments of the Last is a title mentioned, but its specific subject and current location would require further research to elaborate upon.

Fraser's achievement lay in his consistent production of well-crafted, engaging paintings that found a ready market. His election to the Royal Scottish Academy was a significant professional milestone, confirming his status among his peers.

Contemporaries and the Scottish Artistic Milieu

Alexander Fraser the Elder worked within a rich and evolving Scottish art scene. His primary connection, David Wilkie, was a towering figure whose influence extended to many. Wilkie's success with works like The Blind Fiddler and Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Waterloo Dispatch set a benchmark for British genre painting.

Other important Scottish contemporaries, besides his classmate Sir John Watson Gordon, included:

Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840): A leading landscape painter and influential teacher at the Trustees' Academy. His sons, including Patrick Nasmyth (1787-1831), known as the "English Hobbema" for his detailed rustic landscapes, were also part of this artistic environment.

Sir William Allan (1782-1850): A friend of Wilkie, known for his historical scenes, particularly those set in Russia and Scotland. He also became President of the Royal Scottish Academy.

Andrew Geddes (1783-1844): A fine portraitist and etcher, who also produced genre and historical subjects.

John Burnet (1784-1868): An engraver who famously translated Wilkie's paintings into prints, popularizing them widely. Burnet was also a painter and a writer on art.

William Kidd (1796-1863): Another Scottish genre painter who, like Fraser, assisted Wilkie for a time and was influenced by his style, often depicting scenes of Scottish life and animals.

Walter Geikie (1795-1837): Known for his spirited etchings and drawings of everyday Scottish life, particularly street scenes and characters from humble backgrounds.

Thomas Duncan (1807-1845): A highly talented historical and portrait painter, whose promising career was cut short by his early death. He was a prominent figure in the Royal Scottish Academy.

Robert Scott Lauder (1803-1869): An important historical painter who later became a highly influential teacher at the Trustees' Academy, shaping a subsequent generation of Scottish artists. His brother, James Eckford Lauder (1811-1869), was also a notable historical and genre painter.

Sir George Harvey (1806-1876): Known for his depictions of Covenanters and scenes from Scottish religious history, as well as everyday life. He succeeded Watson Gordon as President of the RSA.

Horatio McCulloch (1805-1867): One of Scotland's foremost landscape painters, celebrated for his grand and romantic views of the Highlands. Fraser was friends with McCulloch and they exhibited together at the RSA.

Samuel Bough (1822-1878): A younger contemporary, also a friend of Fraser, who became a popular landscape and marine painter, known for his vigorous and atmospheric style.

David Octavius Hill (1802-1870): Primarily remembered today for his pioneering photographic work with Robert Adamson, Hill was also a landscape painter and Secretary of the Royal Scottish Academy.

This network of artists, through institutions like the Trustees' Academy and the Royal Scottish Academy, created a supportive and competitive environment that fostered a distinct Scottish school of painting. Fraser was an integral part of this milieu, contributing to its character and development.

Later Years, Personal Life, and Legacy

Information from the provided text suggests some details about Fraser's personal life, though these are sometimes conflated with other individuals named Alexander Fraser, a common Scottish name. Focusing on Alexander Fraser the Elder, the painter: he is recorded as having married. One account mentions a marriage to a Miss Dowchly, with whom he had children, including his son Alexander Fraser Jr., who also became a painter. Another marriage to a daughter of the Weirs family is also noted. Such details, common in biographical records of the time, paint a picture of a family man.

The text mentions that from 1859, Fraser "almost ceased to exhibit new works, and in his later years, he focused on personal creation." This suggests a withdrawal from the more public aspects of an artist's career, perhaps due to age, health, or changing personal circumstances. The mention of personal tragedies, such as the death of a wife and a son (Simon Fraser, though this name needs careful verification in relation to the painter's direct family), could certainly have impacted his later life and productivity. It's plausible that such losses led him to seek more private artistic expression.

Alexander Fraser the Elder died in London on February 15, 1865. His legacy is that of a skilled and dedicated painter who made a significant contribution to Scottish genre and still-life painting. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Wilkie, he was a highly competent and respected artist who captured aspects of Scottish life and character with warmth and precision. His work as Wilkie's assistant placed him at the center of British art for two decades, and his independent paintings were appreciated for their craftsmanship and engaging subject matter.

His influence can be seen in the continuation of genre painting traditions in Scotland. His son, Alexander Fraser Jr. (ARSA), followed in his footsteps as a landscape and genre painter, ensuring the family name continued in Scottish art circles. The broader impact of artists like Fraser the Elder was to help establish a national school of art that was confident in its themes and techniques, drawing inspiration from local life while engaging with broader European artistic traditions.

Influence on Subsequent Art and Art Historical Assessment

Alexander Fraser the Elder's art, characterized by its naturalism, detailed execution, and focus on everyday life, played a role in shaping the trajectory of Scottish painting in the 19th century. His adherence to the principles he absorbed from Dutch masters and through his association with Wilkie reinforced a taste for narrative clarity and careful observation.

Art historians evaluate Fraser as a key figure within the "Wilkie school" of Scottish genre painters. He is praised for his technical proficiency, particularly in rendering textures and details in still life, and for the gentle humour and humanity in his figural compositions. His works are seen as valuable documents of Scottish social customs and material culture of his time. While his style was generally conservative, it was well-suited to the subjects he chose and found favour with middle-class patrons who appreciated recognizable scenes and skilled craftsmanship.

His contribution to landscape painting, including his depictions of specific sites like Rosslyn Chapel, aligns with the broader Romantic-era interest in national scenery and historical monuments. These works helped to popularize such locations and contributed to a growing sense of national identity expressed through art.

The influence of Fraser and his contemporaries can be seen in the work of later Scottish artists who continued to explore themes of rural life, domesticity, and national character, even as artistic styles evolved towards Impressionism and beyond. Artists like John William Fraser (if this refers to a distinct, later artist and not a confusion with Fraser's son or another relative) might well have looked to the earlier generation's dedication to capturing the nuances of Scottish life and landscape.

In conclusion, Alexander Fraser the Elder holds a respected place in the annals of Scottish art. He was a product of the excellent training offered by the Trustees' Academy, a vital collaborator with one of Britain's most famous artists, and a successful independent painter in his own right. His works, found in public collections including the National Galleries of Scotland, continue to be appreciated for their charm, technical skill, and their affectionate portrayal of a bygone era. He was a diligent and talented artist who, through his dedication to his craft, contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art, particularly within its vibrant Scottish dimension.