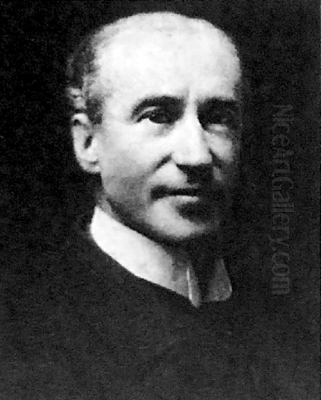

George Henry (1858-1943) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Scottish art, particularly renowned for his pivotal role within the Glasgow School, often referred to as the 'Glasgow Boys'. Born in Irvine, North Ayrshire, Henry's artistic journey took him from the classrooms of the Glasgow School of Art to the forefront of a movement that challenged the established norms of late Victorian painting in Scotland. His work, encompassing both evocative landscapes and striking portraits, is celebrated for its vibrant use of colour, decorative qualities, and an innovative engagement with international artistic trends, most notably the influence of Japanese art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

George Henry's artistic education began formally at the esteemed Glasgow School of Art. This institution provided him with foundational skills, but his development was significantly shaped by further study, particularly in the studio of William York Macgregor. Macgregor, himself an influential painter and a central figure around whom many of the younger, more progressive artists gathered, likely instilled in Henry a commitment to observing nature closely, a hallmark of the burgeoning Glasgow School's approach.

The artistic environment in Glasgow during the late 19th century was one of burgeoning confidence and a desire to break free from the perceived constraints and sentimentalism often associated with the Edinburgh-based Royal Scottish Academy. Artists like Henry sought a more direct, robust, and truthful mode of expression, looking towards contemporary European movements, such as French Realism exemplified by artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, and the aesthetic principles championed by James McNeill Whistler. This period laid the groundwork for Henry's distinctive style.

The Glasgow Boys and the Rise of a New Aesthetic

George Henry quickly became one of the most prominent members of the Glasgow Boys. This loose collective of artists, active primarily from the 1880s through the 1890s, shared a commitment to naturalism, realism, and often worked en plein air (outdoors) to capture the true effects of light and atmosphere. They reacted against the highly finished, often narrative-driven paintings favoured by the academic establishment. Key figures associated with this group, alongside Henry, included James Guthrie, Joseph Crawhall, Arthur Melville, E.A. Walton, John Lavery, and James Paterson.

Henry's early work within this context demonstrated a move away from tight, detailed rendering towards broader handling and a heightened sensitivity to colour and tone. He often painted rural scenes and landscapes, finding inspiration in the Scottish countryside, particularly in areas like Galloway. His approach was less about topographical accuracy and more about conveying the mood and decorative potential of the landscape.

Innovation in Colour and Decoration: The Galloway Landscapes

A defining characteristic of George Henry's contribution to the Glasgow School was his bold and innovative use of colour and his embrace of decorative pattern. This is perhaps best exemplified in works such as A Galloway Landscape. Painted with rich, saturated hues and a flattened perspective that emphasizes the surface pattern, this work marked a significant departure from traditional landscape painting. It showcased an interest in colour not just for descriptive purposes, but for its emotional and decorative impact.

This move towards a more colourist and decorative style set Henry, along with close associates like E.A. Hornel, somewhat apart even within the Glasgow Boys, pushing the boundaries of naturalism towards something more expressive and symbolic. These works were considered radical by many contemporaries but were crucial in establishing the Glasgow School's reputation for modernity and innovation both nationally and internationally. His painting Noon (1885) and River Landscape by Moonlight (1887) also date from this formative period, showing his developing interest in atmospheric effects and tonal harmony.

Collaboration and Experimentation: The Druids

The spirit of camaraderie and shared artistic exploration among the Glasgow Boys often led to collaboration. One of the most famous examples is The Druids: Bringing in the Mistletoe, a work jointly painted by George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel around 1890. This large, ambitious painting, depicting a procession of ancient Celtic figures, is remarkable for its rich, textured surface, achieved through heavy impasto, and its complex, decorative composition.

The Druids represents a culmination of their shared interest in symbolism, rich colour, and surface texture. It was a bold statement, moving beyond straightforward naturalism towards a more imaginative and historically evocative subject matter, treated with a thoroughly modern technique. The collaboration itself highlights the close working relationship between Henry and Hornel, who would continue to share artistic adventures. Other works from this period, like Girl in White (1886) and the intriguingly titled Plucking the Stars, further demonstrate his range.

The Journey to Japan and its Lasting Impact

A pivotal moment in George Henry's career, and that of E.A. Hornel, was their journey to Japan in 1893-1894. Funded partly by the Glasgow art dealer Alexander Reid, they spent approximately eighteen months immersing themselves in Japanese culture and art. This was a period when Japonisme – the influence of Japanese art and aesthetics – was already a significant force in European art, impacting Impressionists like Degas and Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh and Gauguin, as well as Whistler.

For Henry, the experience was transformative. He was captivated by the compositional structures, the flat areas of colour, the emphasis on line, and the decorative motifs found in Japanese prints (ukiyo-e) and paintings. This influence is clearly visible in the works he produced during and immediately after his trip, such as Japanese Lady with a Fan (1893-1894) and Geisha (1894). These paintings feature Japanese subjects rendered with bright colours, flattened perspectives, and a strong sense of pattern, integrating his observations into his established style.

While the overt Japanese influence was most pronounced in the years immediately following his return, the experience fundamentally enriched his understanding of colour, composition, and decorative possibilities. It reinforced his move away from purely naturalistic representation and contributed to the sophisticated elegance that would characterise much of his later work. However, unlike some artists who fully adopted Japonisme, Henry eventually synthesized these influences into his own evolving style rather than adhering strictly to Japanese models long-term.

Mature Style and Mastery of Portraiture

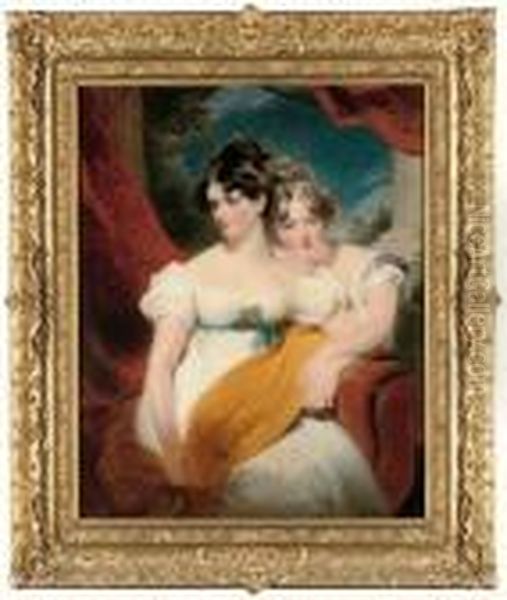

Following his return from Japan and into the early 20th century, George Henry settled primarily in London, although he maintained strong ties with Scotland. While he continued to paint landscapes, his focus increasingly turned towards portraiture. He developed a reputation as a highly skilled portrait painter, sought after for his technical proficiency and elegant style.

His portraits, such as The Black Hat (c. 1920s) and Portrait of a Scottish Gentleman (1922), demonstrate a sophisticated handling of paint, an assured sense of composition, and a continued interest in the decorative qualities of costume and setting. Works like The Blue Gown and The Gray Hat (mentioned as examples of his portraiture skill) further cemented his reputation. While perhaps less overtly experimental than his earlier landscapes or Japanese subjects, these portraits were admired for their technical brilliance and refined aesthetic. Critics noted that his strength lay more in capturing the visual likeness and the textures of fabrics than in deep psychological penetration, but his skill in rendering was undeniable.

His style in this later period can be seen as a return towards a form of realism, but one informed by his earlier experiments with colour and design. The boldness of the Galloway period and the explicit Japonisme were tempered, resulting in works of sophisticated elegance and technical accomplishment that appealed to the Edwardian and later Georgian clientele.

Recognition and Academic Honours

George Henry's talent and contributions to art did not go unrecognized by the establishment he and the Glasgow Boys had once challenged. His growing reputation led to prestigious academic honours. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (ARSA) and became a full Royal Scottish Academician (RSA) in 1902.

His move to London brought further recognition within the English art world. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) and subsequently a full Royal Academician (RA). These accolades signified his acceptance into the highest echelons of the British art establishment and reflected the significant impact he and the Glasgow School had made on the national art scene. He continued to exhibit regularly at these institutions and others throughout his career.

Museum Collections and Legacy

Today, George Henry's works are held in numerous public collections, testifying to his enduring importance. Key institutions include:

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow: Holding significant works, including Japanese Lady with a Fan and likely examples of his earlier Glasgow School period.

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh: Features important pieces like Geisha, showcasing the impact of his Japan trip.

Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town: Collections include works like The Blue Gown, indicating his international reach.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts: Holds examples of his portraiture.

Tate, London: Possesses works representing his contribution to British art.

Other galleries across the UK and internationally also hold examples of his paintings, ensuring his work remains accessible to the public.

George Henry's legacy is multifaceted. He was a crucial figure in the Glasgow School, pushing the group towards greater experimentation with colour and decorative effects. His work, particularly from the late 1880s and early 1890s, helped define the innovative character of the movement. His journey to Japan with Hornel was a landmark event, significantly contributing to the reception and integration of Japanese aesthetics within British art.

While his later work became more conventional, his technical mastery, particularly in portraiture, remained highly respected. He successfully navigated the transition from a radical young painter challenging the establishment to becoming a respected member of it, without entirely losing the distinctive colour sense and design awareness that marked his earlier breakthroughs. He influenced subsequent generations of Scottish artists through his bold use of colour and his role in broadening the horizons of Scottish painting. Alongside contemporaries like John Lavery, Arthur Melville, James Guthrie, and even figures associated with the broader Glasgow Style like Charles Rennie Mackintosh (though in design), Henry helped forge a distinctly modern Scottish artistic identity at the turn of the 20th century.

Conclusion

George Henry remains a pivotal figure in Scottish art history. As a leading member of the Glasgow Boys, he played an instrumental role in revitalizing painting in Scotland, championing naturalism while simultaneously exploring the expressive potential of colour and decoration. His engagement with international trends, particularly Japonisme, brought a new sophistication and vibrancy to his work and influenced his peers. From the bold, colourful landscapes of Galloway to the elegant portraits of his later career, Henry demonstrated remarkable technical skill and a distinctive artistic vision. His election to both the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy in London confirmed his status, securing his legacy as one of Scotland's most important painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.