Introduction: The People's Painter

Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) stands as one of the most significant figures in British art during the early nineteenth century. A native of Scotland, Wilkie rose from provincial beginnings to become a celebrated member of the London art establishment, Painter in Ordinary to the King, and a Knight of the Realm. He earned the affectionate title "The People's Painter" for his engaging and meticulously detailed depictions of everyday life, primarily focusing on rural and domestic scenes. His work bridged the gap between the high art traditions of historical painting and the growing public appetite for relatable, narrative subjects, leaving an indelible mark on the development of genre painting in Britain. His journey reflects a remarkable talent combined with astute observation and an ability to connect with a broad audience through themes of community, humour, and pathos.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Scotland

David Wilkie was born on November 18, 1785, in the village of Cults, Fife, Scotland. His father was the parish minister, and the young Wilkie grew up immersed in the rhythms and characters of rural Scottish life, an environment that would profoundly shape his artistic vision. Showing an early aptitude for drawing, he was enrolled, despite some initial reluctance from the authorities due to his perceived lack of academic polish, at the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh in 1799. There, under the tutelage of the historical painter John Graham, Wilkie honed his skills in draughtsmanship and began to develop his interest in depicting scenes from life around him. Even in these formative years, his keen eye for detail and human interaction was evident. His early work, such as Pitlessie Fair (1804), painted while still a teenager, already showcased his talent for orchestrating complex multi-figure compositions drawn directly from his observations of local gatherings, demonstrating a nascent connection to the traditions of Dutch and Flemish genre painting.

Arrival in London and the Influence of the Dutch Masters

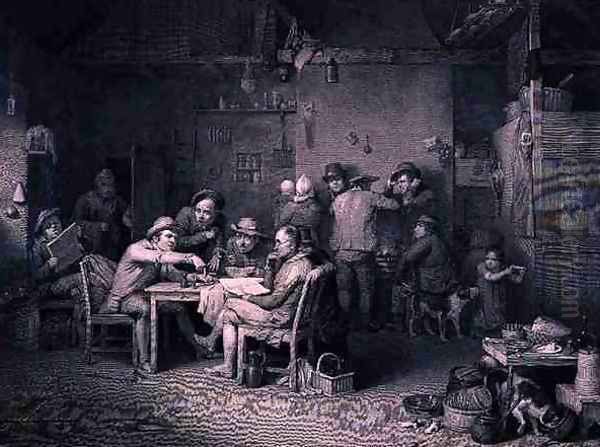

In 1805, seeking greater opportunities and exposure, Wilkie moved to London and enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. London's vibrant art scene provided fertile ground for his ambitions. He quickly absorbed the lessons of the Old Masters available in collections and exhibitions, finding particular resonance with the seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish genre painters. Artists like David Teniers the Younger and Adriaen van Ostade became significant touchstones for Wilkie. He admired their technical skill, their detailed rendering of textures and interiors, and their ability to capture the nuances of peasant life and domesticity with both realism and often a gentle humour. This influence was readily apparent in the works that soon brought him widespread acclaim.

Wilkie's breakthrough came swiftly. His painting Village Politicians, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1806, caused a sensation. It depicted a group of villagers engaged in animated discussion in a rustic interior, rendered with a precision and narrative clarity that captivated audiences and critics alike. This success was immediately followed by The Blind Fiddler (1806), another masterpiece of observation and sentiment, portraying a travelling musician entertaining a humble family. The painting's careful composition, expressive figures, and meticulous detail solidified Wilkie's reputation as a major new talent. Patrons, including prominent collectors like Sir George Beaumont, recognized his unique ability to elevate scenes of ordinary life to the level of high art, albeit through a different lens than the grand historical narratives favoured by predecessors like Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Consolidation of Fame and Royal Patronage

The years following his initial successes saw Wilkie consolidate his position within the London art world. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1809 and became a full Royal Academician (RA) just two years later, in 1811, at the remarkably young age of 26. His works continued to be highly anticipated events at the annual Royal Academy exhibitions. Paintings such as The Letter of Introduction (1813), Distraining for Rent (1815), and the lively The Penny Wedding (1819) further cemented his fame. These works demonstrated his mastery of complex group compositions, his skill in capturing individual character and emotion, and his talent for telling a story within a single frame. His meticulous technique involved careful preparatory drawings and a layered application of paint, achieving a high degree of finish that appealed to contemporary tastes.

Wilkie's popularity extended beyond the exhibition halls. His paintings were widely disseminated through engravings, produced often in collaboration with skilled printmakers, making his images accessible to a broader public and significantly contributing to his income and renown. This practice was shared with contemporaries like his fellow Scot, the portraitist Sir Henry Raeburn, whose own work defined Scottish portraiture in this era. Wilkie's ability to capture relatable human experiences resonated deeply with the public, establishing genre painting as a commercially viable and critically respected field in Britain.

The 'Waterloo Dispatch' and Peak Popularity

Perhaps the pinnacle of Wilkie's popular acclaim was reached with his painting Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Waterloo Dispatch (completed 1822). Commissioned by the Duke of Wellington, the victor of Waterloo himself, the painting depicts a group of war veterans eagerly receiving news of the decisive battle. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1822, the work was an unprecedented success. Crowds thronged to see it, drawn by its patriotic subject matter, its detailed portrayal of the varied reactions of the pensioners, and Wilkie's masterful handling of the complex scene. Contemporary accounts report that barriers had to be erected to protect the painting from the sheer volume of enthusiastic viewers, a testament to its extraordinary impact. This work perfectly encapsulated Wilkie's ability to blend historical significance with intimate human detail, creating a powerful and accessible image of a shared national moment.

His success brought him to the attention of the monarchy. Following the death of Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1830, Wilkie was appointed Painter in Ordinary to King George IV. He retained this prestigious position under King William IV and subsequently under Queen Victoria upon her accession in 1837. This royal appointment not only signified his pre-eminence in the British art world but also led to numerous royal commissions, primarily portraits, although he continued to produce genre and historical subjects. In 1836, his status was further confirmed when he received a knighthood from William IV.

The Grand Tour: Health, Loss, and a New Artistic Direction

The mid-1820s marked a significant turning point in Wilkie's life and art. Suffering from poor health, possibly exacerbated by stress and the meticulous demands of his painting technique, and deeply affected by the deaths of his mother and two brothers, Wilkie sought recuperation and new inspiration abroad. From 1825 to 1828, he embarked on an extended tour of the European continent, visiting France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and, crucially, Spain. This journey, undertaken initially for health reasons, had a profound and transformative effect on his artistic style.

While in Italy, he studied the works of the Italian Renaissance masters, but it was his time in Spain that proved most decisive. In Madrid and Seville, Wilkie encountered the masterpieces of the Spanish Golden Age, particularly the works of Diego Velázquez and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. He was struck by their bolder brushwork, richer palettes, dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and profound psychological depth, especially in portraiture and religious scenes. Compared to the tighter, more detailed finish of his earlier, Dutch-influenced style, the Spanish masters offered a model of greater breadth, freedom, and expressive power. Wilkie spent considerable time studying and copying works in the Prado Museum, absorbing the lessons of Velázquez's realism and Murillo's emotive warmth.

Later Career: A Broader Canvas

Upon his return to London in 1828, Wilkie's painting style had noticeably changed. His brushwork became looser and more fluid, his colours richer and deeper, and his compositions often grander in scale and conception. While some patrons and critics accustomed to his earlier manner were initially hesitant, Wilkie embraced this new direction. He began to tackle historical subjects with greater frequency and ambition, often drawing on themes from British and European history, as well as scenes inspired by his travels. Works from this period include The Defence of Saragossa (inspired by the Peninsular War), The Guerilla Council of War, and the significant historical painting The Preaching of Knox before the Lords of the Congregation, 10th June 1559 (completed 1832), which depicted a pivotal moment in the Scottish Reformation.

He continued to paint genre scenes, but often with a broader touch and sometimes exploring different social settings, as seen in The First Ear-Ring (c. 1834-35) and The Peep-o’-Day Boys’ Cabin in the West of Ireland (1835-36), the latter reflecting an interest in Irish subjects. His portraiture also took on a new gravitas, influenced by his study of Velázquez and Anthony van Dyck. Despite the stylistic shift, his fundamental interest in narrative and human character remained central to his art. He also maintained connections with younger artists, sharing his experiences and insights, influencing figures like the orientalist painter John Frederick Lewis, who would later follow in Wilkie's footsteps by travelling to Spain and the East.

The Final Journey to the East and Death at Sea

In August 1840, Wilkie embarked on his final journey, travelling to the Middle East. His primary purpose was to gather authentic material for biblical paintings, a long-held ambition, and potentially to paint a portrait of the young Ottoman Sultan, Abdülmecid I, as a commission for Queen Victoria. He travelled via the Netherlands and Germany to Constantinople (Istanbul), then onwards to Smyrna, Rhodes, Beirut, and Jerusalem, before reaching Alexandria in Egypt. He produced numerous sketches and studies during this trip, capturing the landscapes, architecture, and people of the region with his characteristic observational skill.

Tragically, on the return voyage from Alexandria aboard the steamship SS Oriental, Wilkie fell ill. His condition rapidly deteriorated, and he died suddenly on the morning of June 1, 1841, as the ship sailed near Gibraltar. Due to quarantine regulations and the heat, the captain refused to bring the body ashore at Gibraltar. Consequently, Sir David Wilkie was buried at sea that evening off the coast of Gibraltar. His unexpected death sent shockwaves through the British art world. His friend and fellow Academician, J.M.W. Turner, commemorated the event in his hauntingly atmospheric painting Peace - Burial at Sea (exhibited 1842), a poignant tribute to the lost master.

Wilkie's Artistic Style: Observation, Narrative, and Evolution

Wilkie's art is characterized by its strong narrative impulse, its foundation in close observation, and its stylistic evolution. His early works, indebted to the Dutch Golden Age, are marked by meticulous detail, carefully rendered textures, complex but clear compositions, and a warm, often interior, lighting. He excelled at capturing the small dramas and comedies of everyday life, investing ordinary people and domestic settings with significance and emotional resonance. His figures are individuals, their poses, gestures, and expressions contributing to the overall story. This "anecdotal style," as it has been called, focused on legibility and relatable human experience.

Following his continental tour, particularly his exposure to Spanish painting, his style broadened significantly. Brushwork became more visible and energetic, colour palettes often became richer and incorporated bolder contrasts of light and shadow, and the overall effect was less detailed but arguably more atmospheric and emotionally direct. While he never fully abandoned genre subjects, his later work showed an increased engagement with historical themes and portraiture, tackled with a newfound confidence and breadth inspired by masters like Velázquez and Murillo. Throughout his career, however, his work remained grounded in skilled draughtsmanship and a fundamental interest in human character and storytelling.

Influence, Contemporaries, and Legacy

Sir David Wilkie exerted a considerable influence on British art. He is widely regarded as a pivotal figure in establishing genre painting as a major strand within the British school, elevating it from mere illustration to a respected art form. His success paved the way for subsequent generations of genre painters, including figures like William Powell Frith, whose crowded Victorian scenes owe a debt to Wilkie's narrative compositions, and Sir William Allan, a fellow Scot who also painted historical and genre subjects. His detailed realism and focus on contemporary life can also be seen as a precursor, albeit indirectly, to some aspects of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's concerns later in the century.

He navigated the complex art world of his time, interacting with major figures. His relationship with the history painter Benjamin Robert Haydon was complex, marked by both friendship and rivalry. He collaborated successfully with Sir Henry Raeburn on prints. He succeeded Sir Thomas Lawrence as the principal painter to the monarch. He was a contemporary of the great landscape painters J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, though his focus remained firmly on the human figure and narrative. His work offered a distinct alternative to both the grand manner of historical painting inherited from Reynolds and the burgeoning dominance of landscape. He demonstrated that scenes of ordinary life, rendered with skill and empathy, could achieve widespread popularity and critical acclaim. His influence extended beyond Britain, with his works admired and collected across Europe.

Critical Reception and Enduring Reputation

During his lifetime, Wilkie enjoyed immense popularity and critical success. He was celebrated for his technical skill, his observational acuity, his gentle humour, and his ability to capture the national character, particularly in his Scottish scenes. His paintings commanded high prices, and engravings after his work were immensely popular. He was seen as a successor to William Hogarth in the realm of British narrative art, though Wilkie generally lacked Hogarth's sharp satirical edge, favouring instead a more sympathetic portrayal of his subjects.

Later art historical assessments have sometimes been more measured. Compared to the revolutionary innovations of his contemporaries Turner and Constable, Wilkie's art can appear more conservative, particularly his reliance on Old Master prototypes. His later, broader style, influenced by Spain, was not universally acclaimed at the time and is sometimes seen as less distinctive than his earlier, meticulously detailed work. Nevertheless, his importance in the history of British art is undeniable. He revitalized and popularized genre painting, created iconic images of British life, and demonstrated a remarkable capacity for stylistic development. "The People's Painter" remains a key figure for understanding the art and culture of early nineteenth-century Britain, an artist whose work continues to engage viewers with its blend of technical mastery, narrative skill, and humane observation.

Conclusion: A Master of British Narrative

Sir David Wilkie's career charts a remarkable trajectory from rural Scotland to the heart of the London art establishment and international renown. His early, Dutch-inspired genre scenes captured the public imagination with their detail, warmth, and relatable narratives, earning him the title "The People's Painter." His later works, transformed by his encounter with the Spanish masters, demonstrate a broadening of style and ambition, encompassing grander historical themes and more expressive techniques. From The Blind Fiddler to the Chelsea Pensioners and The Preaching of Knox, his paintings offer vivid insights into the social fabric, historical consciousness, and artistic tastes of his time. As a master storyteller, a meticulous observer of human nature, and a pivotal figure in the development of British genre painting, Wilkie's legacy endures, his works continuing to be admired in major collections around the world, including the National Gallery in London, the National Galleries of Scotland, the Royal Collection, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.