Alexander Helwig Wyant stands as a significant figure in the pantheon of nineteenth-century American landscape painters. His artistic journey charts a compelling evolution from the detailed realism associated with the Hudson River School to the evocative, atmospheric subtlety of Tonalism. Wyant's work is celebrated for its poetic sensitivity, its masterful handling of light and mood, and its intimate connection to the American wilderness, particularly the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains. His life, marked by both artistic dedication and personal adversity, offers a fascinating glimpse into the changing landscape of American art during a period of profound transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

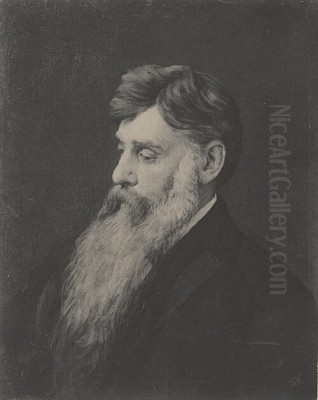

Born in Evans Creek, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, on January 11, 1836, Alexander Wyant's early life provided little indication of his future artistic prominence. His family later relocated to Defiance, Ohio. His initial career path led him into practical trades; he worked for a time as a harness maker and later as a sign painter. These early experiences, while seemingly distant from fine art, likely honed his manual dexterity and perhaps instilled an appreciation for craftsmanship.

The pivotal moment in Wyant's artistic awakening occurred around 1857. During a visit to Cincinnati, he encountered an exhibition of landscape paintings by George Inness. Inness, already a rising figure whose work was moving beyond the strictures of the early Hudson River School towards a more personal and expressive style, deeply impressed the young Wyant. The encounter ignited a passion and a determination to pursue painting as a serious vocation. This inspiration proved decisive, setting Wyant on a new course.

Fueled by this newfound ambition, Wyant sought out Inness. In 1859, he traveled to New York City specifically to meet the artist whose work had so profoundly affected him. Inness offered encouragement, recognizing the potential in the aspiring painter from Ohio. This meeting was crucial, providing not only validation but also practical advice and likely opening doors within the New York art community.

Formative Years and Patronage

Returning to Ohio, Wyant found crucial support from Nicholas Longworth, a prominent Cincinnati patron of the arts. Longworth, known for his discerning eye and support of local talent (including sculptor Hiram Powers), saw promise in Wyant. He provided financial assistance that enabled Wyant to return to New York City for more formal study in 1860. This patronage was instrumental, allowing Wyant access to training and resources that would have otherwise been unavailable.

Wyant spent about a year studying at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York. While the exact nature of his studies there is not fully documented, it provided him with foundational skills and exposure to the established art world. He began exhibiting his work, showing his first painting at the National Academy in 1864. His early works from this period often reflected the prevailing influence of the Hudson River School, characterized by detailed rendering and a focus on the grandeur of the American landscape.

His connection with George Inness remained important during these formative years. While not a formal student-teacher relationship in the traditional sense, Inness's example and guidance were significant. Wyant absorbed Inness's evolving approach to landscape, which emphasized mood and subjective interpretation over purely topographical accuracy, planting the seeds for Wyant's later stylistic development.

European Sojourn and Broadening Influences

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Wyant recognized the value of European study. In 1865, he embarked on a trip abroad, seeking to refine his technique and broaden his artistic horizons. He traveled first to Germany, settling for a time in Karlsruhe. There, he briefly studied with Hans Fredrik Gude, a respected Norwegian painter associated with the Düsseldorf school but known for his realistic and often dramatic Scandinavian landscapes. Gude's emphasis on careful observation and atmospheric effects likely resonated with Wyant.

While in Europe, Wyant also spent time in England and Ireland. This part of his journey proved particularly influential. He was deeply impressed by the works of the great English landscape painters John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. Constable's dedication to capturing the fleeting effects of light and weather on the English countryside, and Turner's dramatic, often turbulent, explorations of light and atmosphere, offered powerful alternatives to the sometimes rigid conventions of the Hudson River School.

Furthermore, Wyant undoubtedly absorbed the influence of the French Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Théodore Rousseau. Although he may not have studied directly with them, their work was widely discussed and admired. The Barbizon painters' emphasis on painting outdoors (en plein air), their focus on intimate woodland scenes, and their pursuit of tonal harmony and poetic mood struck a chord with Wyant and significantly shaped his developing aesthetic. He returned to America in 1866, his artistic vision enriched and subtly transformed by these European encounters.

The Hudson River School Connection

Upon his return to New York, Wyant initially worked within the stylistic parameters generally associated with the second generation of the Hudson River School. This movement, pioneered by artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, celebrated the unique beauty and perceived divinity of the American wilderness. Later practitioners, including Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, often emphasized panoramic vistas and dramatic natural phenomena, rendered with meticulous detail.

Wyant's early landscapes often shared characteristics with this tradition. Works from the mid-to-late 1860s frequently feature recognizable locations, a relatively high degree of detail, and a clear, bright light. His painting The Mohawk Valley (1866), now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, exemplifies this phase. It presents a broad, expansive view, carefully composed and rendered with considerable attention to topographical features and a cool, clear palette. It demonstrates his technical skill and his alignment, at this stage, with the established school of American landscape painting.

However, even in these earlier works, hints of Wyant's later Tonalist sensibility can sometimes be discerned. There is often a quietude, a subtle emphasis on atmosphere, that distinguishes his work from the more overtly spectacular canvases of some contemporaries. He seemed less interested in pure documentation or high drama and more inclined towards capturing a specific, often tranquil, mood within the landscape. This underlying inclination would become increasingly dominant in the years to follow.

A Defining Moment: The Stroke and Artistic Adaptation

A significant turning point in Wyant's life and art occurred in 1873. He joined a government-sponsored geological survey expedition led by Lieutenant George M. Wheeler, tasked with exploring territories west of the 100th meridian, specifically in Arizona and New Mexico. The journey was arduous, traversing challenging terrain under difficult conditions. During this expedition, Wyant suffered a debilitating paralytic stroke.

The stroke severely affected his right side, leaving his dominant right arm and hand largely paralyzed. For a painter, particularly one trained in the detailed rendering techniques common at the time, this was a potentially career-ending catastrophe. However, Wyant displayed remarkable resilience and determination. Faced with this immense physical challenge, he painstakingly taught himself to paint with his left hand.

This forced adaptation had a profound, though perhaps initially unintended, impact on his artistic style. Working with his non-dominant hand necessitated a change in technique. It likely encouraged a looser, broader application of paint and a shift away from minute detail towards capturing the overall effect and essence of a scene. This physical limitation, paradoxically, may have accelerated his move towards the more suggestive, atmospheric style that would define his mature work and align him with the burgeoning Tonalist movement.

The Rise of Tonalism

The later decades of the 19th century saw the emergence of Tonalism as a significant force in American art. Influenced by the Barbizon School and the aesthetic theories of artists like James McNeill Whistler, Tonalism represented a departure from the detailed realism of the Hudson River School. Tonalist painters favored intimate, often contemplative scenes, rendered in a limited palette of closely related hues – typically greens, browns, grays, and muted blues. Their primary aim was to evoke mood, atmosphere, and a sense of poetic mystery rather than to provide a literal transcription of nature.

Alexander Helwig Wyant, alongside his early inspiration George Inness and contemporaries like Homer Dodge Martin and Dwight Tryon, became one of the leading exponents of American Tonalism. His work from the mid-1870s onwards increasingly embodies the core tenets of this style. His canvases became quieter, more introspective, focusing on the subtle interplay of light and shadow, often depicting scenes at twilight, dawn, or on overcast days.

Wyant's Tonalist landscapes are characterized by their soft edges, simplified forms, and rich, atmospheric depth. He masterfully manipulated subtle variations in color and tone to create a powerful sense of mood, often melancholic or deeply serene. The meticulous detail of his earlier work gave way to a more suggestive approach, inviting the viewer to engage emotionally and imaginatively with the scene. He sought the soul of the landscape, its inherent poetry, rather than its mere physical appearance.

Signature Themes and Locations

While his early work sometimes depicted grander vistas, Wyant's mature Tonalist style found its most characteristic expression in more intimate encounters with nature. He was particularly drawn to the landscapes of the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, spending considerable time in and around Keene Valley. He also frequented the Catskill Mountains, establishing a studio in Arkville later in his life. These regions provided the inspiration for many of his most celebrated works.

His preferred subjects were often quiet woodland interiors, secluded streams, hazy mountain slopes, and the transitional moments of the day or seasons. He had a particular affinity for autumn landscapes, capturing the subtle, melancholic beauty of the season through his masterful use of muted golds, russets, and browns. Open fields bordered by woods, often under soft, diffused light, were recurring motifs.

Unlike some Hudson River School painters who sought out dramatic or exotic locales, Wyant found profound beauty in the familiar, often overlooked corners of the northeastern landscape. His paintings rarely feature overt narrative elements or human figures; instead, the focus is entirely on the mood and atmosphere of the natural world itself. His work conveys a deep, personal connection to these places, rendered with a quiet intensity and poetic grace.

Representative Works

Examining specific works highlights Wyant's artistic evolution and Tonalist mastery. The Mohawk Valley (1866), mentioned earlier, represents his connection to the Hudson River School tradition with its panoramic scope and detailed rendering. It showcases his technical proficiency in capturing the specifics of a location under clear, bright light.

In contrast, later works demonstrate his full embrace of Tonalism. An October Day (c. 1888-1892) immerses the viewer in the soft light and gentle melancholy of autumn. The forms of trees and land are suggested rather than sharply defined, enveloped in a hazy atmosphere. The palette is restricted, dominated by warm earth tones and soft grays, creating a unified, harmonious mood.

Near the Dividing Fence (c. 1885) offers another quintessential Tonalist scene. It depicts a simple rural landscape, likely observed near his Arkville home. The focus is on the subtle gradations of tone in the sky and fields, the soft silhouettes of trees against the horizon, and the overall feeling of quietude and rural simplicity. The brushwork is looser, the details minimal, allowing the atmospheric effect to dominate.

Other notable works include View in County Kerry (1870s), reflecting his travels abroad but interpreted through an increasingly Tonalist lens, and numerous depictions of the Adirondack and Catskill wilderness, often titled simply Landscape, Sunset, or In the Woods. Each captures a specific, fleeting moment of light and mood, rendered with his characteristic sensitivity and restraint.

Professional Life and Associations

Throughout his career, Wyant actively participated in the New York art world. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1868 and became a full Academician in 1869, signifying his acceptance within the established art community. His works were regularly included in the Academy's annual exhibitions.

Wyant was also instrumental in the founding of the American Watercolor Society in 1866, serving as one of its early members alongside artists like Samuel Colman. This involvement highlights his proficiency in watercolor, a medium well-suited to capturing the atmospheric effects he increasingly sought in his oils. He maintained a studio in New York City for many years, even while spending significant time painting in the countryside. He occasionally opened his own gallery space to exhibit his work directly to patrons.

Despite the physical limitations imposed by his stroke, Wyant remained a productive artist until his death. He continued to refine his Tonalist vision, creating works that were highly sought after by collectors who appreciated their quiet beauty and poetic depth. He was part of a circle of artists who were moving American landscape painting in new directions, away from literalism towards more personal and expressive interpretations of nature.

Wyant and His Contemporaries

Wyant's artistic journey unfolded alongside many other significant American painters. His relationship with George Inness was foundational, evolving from early inspiration to a shared path towards Tonalism, though each maintained a distinct artistic personality. Wyant's Tonalism is often seen as quieter and perhaps more consistently melancholic than Inness's more varied and sometimes spiritually charged landscapes.

He is frequently grouped with Homer Dodge Martin as a key figure in Tonalism. Both artists shared an affinity for muted palettes and evocative moods, often drawing inspiration from the Barbizon school. Other prominent Tonalists whose work resonates with Wyant's include Dwight W. Tryon, J. Francis Murphy, and Ralph Albert Blakelock, each exploring nuanced atmospheric effects and subjective responses to nature.

While stylistically distinct, Wyant worked during the same era as Winslow Homer, another giant of American painting. Homer's powerful realism and focus on narrative and the human struggle against nature offer a compelling contrast to Wyant's introspective, atmospheric landscapes. Wyant's European influences, Constable and Turner, connect him to a broader tradition of landscape painting, while his engagement with Barbizon ideas links him to French contemporaries like Corot and Daubigny. His work represents a uniquely American synthesis of these various influences, filtered through his personal sensibility and experience.

Legacy and Influence

Alexander Helwig Wyant's influence extended to the next generation of American landscape painters. His mastery of Tonalism provided a model for artists seeking alternatives to both the detailed realism of the Hudson River School and the brighter palette of Impressionism. Artists like Bruce Crane clearly absorbed lessons from Wyant, blending Tonalist sensibilities with Barbizon influences in his own pastoral landscapes. Edward Mitchell Bannister, an African American painter associated with Tonalism, also created works that share Wyant's emphasis on mood and atmosphere. Charles Warren Eaton, known as "the pine tree painter," continued the Tonalist tradition into the early 20th century, echoing Wyant's love for woodland scenes and twilight effects.

Although highly regarded during his later years and immediately after his death, Wyant's reputation, like that of many Tonalist painters, experienced a decline during the mid-20th century as modernist aesthetics came to dominate. However, a renewed appreciation for 19th-century American art has led to a resurgence of interest in his work. Art historians and collectors now recognize his crucial role in the transition from the Hudson River School to more modern modes of landscape painting.

Today, Wyant is acknowledged as one of the foremost American Tonalist painters. His works are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and many others. His paintings continue to resonate with viewers for their quiet beauty, their technical mastery, and their profound, poetic connection to the American landscape.

Conclusion

Alexander Helwig Wyant's life and art exemplify dedication, resilience, and a deep engagement with the natural world. From his early days as a sign painter in Ohio to his emergence as a leading figure of American Tonalism, his journey was one of continuous artistic growth and refinement. Inspired by Inness, shaped by European masters like Constable and the Barbizon painters, and ultimately forged by personal adversity, Wyant developed a distinctive style characterized by atmospheric depth, subtle coloration, and profound emotional resonance. His intimate, moody landscapes of the Adirondacks and Catskills capture the poetic essence of the American wilderness, securing his place as a pivotal and enduringly appealing figure in the history of American art. His legacy lies not only in his beautiful canvases but also in his contribution to the evolution of landscape painting in America, bridging the gap between 19th-century realism and the more subjective approaches that followed.