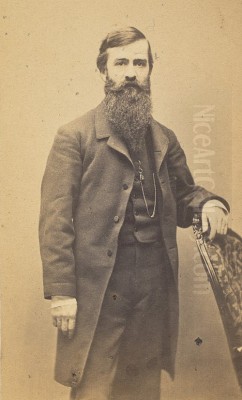

Jervis McEntee (1828-1891) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure within the second generation of the Hudson River School, America's first true school of landscape painting. While his contemporaries often sought the sublime and the spectacular in nature, McEntee carved a unique niche for himself, becoming the preeminent painter of the melancholic, introspective beauty of autumn and early winter. His canvases, imbued with a quiet poetry and a palpable sense of nostalgia, offer a distinctive counterpoint to the grander visions of some of his peers. Beyond his artistic contributions, McEntee left behind an invaluable legacy in his detailed diaries, which provide an unparalleled window into the life of a 19th-century American artist, his social circles, and the evolving art world of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on July 14, 1828, in Rondout, New York, a bustling town on the Hudson River, Jervis McEntee was immersed from a young age in the very landscapes that would later define his artistic career. His father, James McEntee, was an engineer involved with the Delaware and Hudson Canal, a significant artery of commerce that shaped the region. This connection to the land, both in its natural state and as it was being transformed by human endeavor, likely played a role in fostering his early appreciation for the environment. The McEntee family cultivated a love for nature, which undoubtedly nurtured young Jervis's burgeoning interest in art.

His formal artistic training began relatively late compared to some of his peers. After trying his hand at business for a few years in New York City, a venture that proved unsuccessful, McEntee returned to Rondout around 1848. It was in 1850, at the age of 22, that he embarked on a more serious artistic path, seeking instruction from Frederic Edwin Church, who was already an established star of the Hudson River School. Church, only two years McEntee's senior, had himself been a student of Thomas Cole, the acknowledged founder of the movement. This tutelage, though perhaps not lengthy, was pivotal, placing McEntee directly within the lineage of the Hudson River School's leading figures.

During this formative period and in the years that followed, McEntee forged deep and lasting friendships with several other artists who would become prominent members of the Hudson River School. Among these were Sanford Robinson Gifford, whose atmospheric luminism would offer a fascinating contrast to McEntee's more somber tones, and Worthington Whittredge, known for his detailed woodland interiors. These relationships, built on shared artistic aspirations and sketching expeditions, would provide crucial support and camaraderie throughout their careers.

The Hudson River School and McEntee's Place

The Hudson River School, flourishing from roughly the 1820s to the 1870s, was more a shared sensibility and geographical focus than a formal institution. Its artists were united by a belief in the spiritual and aesthetic significance of the American landscape, particularly the Hudson River Valley, the Catskill Mountains, the Adirondacks, and New England. Early figures like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand emphasized detailed realism combined with a romantic, often allegorical, interpretation of nature as a reflection of divine creation and national identity.

McEntee emerged as part of the school's second generation, active from the mid-19th century. This group, which included Church, Gifford, Whittredge, Albert Bierstadt, and John Frederick Kensett, often expanded their geographical horizons, depicting scenes from South America, the Arctic, and the American West. While some, like Church and Bierstadt, became famous for their monumental canvases of exotic and dramatic locales, McEntee remained largely devoted to the more intimate and familiar landscapes of the American Northeast.

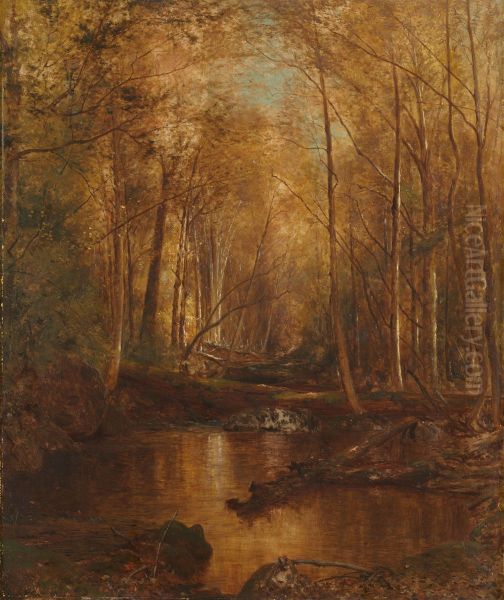

His contribution was unique. He eschewed the vibrant greens of summer and the dazzling spectacle of peak autumn foliage favored by many. Instead, McEntee was drawn to what he termed the "sombreness of late autumn, the pathos of the declining year." His landscapes are often characterized by muted palettes, bare branches, overcast skies, and a pervasive sense of quietude and introspection. This focus on the transitional, more melancholic aspects of nature set him apart and became his signature.

Artistic Style: The Poetry of Melancholy

Jervis McEntee's artistic style is distinguished by its subtlety, its emotional resonance, and its consistent focus on the later seasons. He was a master of capturing the specific atmospheric conditions of late autumn and early winter – the chill in the air, the dampness of fallen leaves, the first dustings of snow. His works are less about grand pronouncements and more about quiet contemplation.

A Palette of Autumn and Winter: McEntee's color choices were typically subdued, favoring browns, grays, ochres, and muted reds and oranges. He excelled at depicting the delicate tracery of leafless branches against a leaden sky, or the way a low sun might cast long, somber shadows across a frosty field. While some critics of his time found his work too somber or repetitive, others recognized the profound emotional depth he achieved through this focused palette. His paintings evoke a sense of nostalgia, a reflection on the passage of time and the cyclical nature of life.

Attention to Detail and Light: Despite the overall moodiness, McEntee's paintings are rich in carefully observed detail. He rendered the texture of bark, the specific forms of rocks, and the delicate structure of winter weeds with precision. His handling of light was crucial to establishing the mood of his scenes. He often favored the diffused light of an overcast day or the weak, raking light of late afternoon, which could imbue his landscapes with a poignant glow. This careful modulation of light and shadow contributed significantly to the poetic quality of his work.

Influence of the Barbizon School: Like many American artists of his generation, McEntee was aware of and likely influenced by the French Barbizon School. Painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean-François Millet emphasized a more direct and unidealized approach to landscape, often focusing on tonal harmonies and capturing specific atmospheric effects. McEntee's preference for intimate, mood-driven scenes and his tonal sensitivity align with Barbizon principles, though he always filtered these influences through his distinctly American sensibility and his personal connection to the landscapes he depicted.

Small Scale, Intimate Focus: McEntee generally preferred smaller canvases, which suited his intimate and introspective subject matter. His works often invite close viewing, allowing the observer to become absorbed in the subtle details and the carefully constructed atmosphere. This contrasts with the panoramic ambitions of artists like Church or Bierstadt, whose large-scale works aimed to overwhelm the viewer with the grandeur of nature. McEntee's aim was more personal, seeking to evoke a specific feeling or memory.

Representative Works: Capturing the "Sober Sadness of the Declining Year"

McEntee's body of work is remarkably consistent in its thematic concerns and stylistic approach. Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his artistic vision.

The Melancholy Days Have Come (c. 1860s, various versions): Taking its title from William Cullen Bryant's poem "The Death of the Flowers," this subject, which McEntee revisited, perfectly encapsulates his artistic temperament. These paintings typically depict a late autumn scene with bare trees, a somber sky, and perhaps a solitary figure, evoking a sense of quiet sorrow and the fading of the year. The title itself underscores the literary and poetic sensibility that often informed his work.

Autumn Landscape (various dates and titles): McEntee produced numerous works simply titled Autumn Landscape or with similar descriptive names. These often feature the rolling hills and wooded valleys of the Catskills or surrounding regions. A characteristic example might show a foreground of fallen leaves, a middle ground of skeletal trees, and distant hills shrouded in mist, all rendered in his signature muted palette. These works are less about a specific location and more about capturing the universal feeling of autumn's decline.

October Snow (e.g., 1870, National Academy of Design): McEntee was adept at portraying the transitional moment when autumn gives way to winter. Paintings like October Snow depict landscapes where an early snowfall lightly blankets the still-colorful, or recently fallen, autumn leaves. These works capture a particular kind of stark beauty, the contrast between the lingering warmth of autumn colors and the encroaching cold of winter.

The Edge of the Woods (or Valley Edge): This title, or variations thereof, appears in his oeuvre, often depicting a scene where a dense forest meets an open space, perhaps a valley or a field. In one such work, McEntee might employ a palette of purples, reds, yellows, whites, and blacks to convey the quietude of a winter or late autumn day, focusing on the textures of the trees and the quality of the light filtering through the branches or across the snow.

Winter in the Woods: Similar to his autumnal scenes, McEntee's winter landscapes are not typically about the dazzling brilliance of a sunny, snow-covered day. Instead, he often chose to depict the more somber aspects of winter: the deep woods under a gray sky, the frozen stillness of a stream, or the stark silhouettes of trees against a pale winter light. These works convey a sense of solitude and the quiet endurance of nature.

His paintings, while often melancholic, were not devoid of beauty. McEntee found a profound and poignant beauty in these "sober" aspects of nature, a beauty that resonated with a segment of the art-buying public and with fellow artists who appreciated his unique vision.

The Tenth Street Studio Building: An Artistic Hub

A significant aspect of McEntee's professional life was his long association with the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt and opened in 1857, it was the first purpose-built facility for artists in the United States and quickly became the epicenter of the New York art world. McEntee took a studio there in 1858 and maintained it for much of his career, until shortly before his death.

The building housed studios for many of the most prominent artists of the day, creating a vibrant community. McEntee's neighbors and colleagues in the building included his mentor Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Robinson Gifford, Albert Bierstadt, Worthington Whittredge, John La Farge, Eastman Johnson, and William Merritt Chase, among others. The building's central exhibition gallery and the artists' regular receptions made it a key social and professional hub.

McEntee was a central figure in this community. His diaries are filled with accounts of visits to and from fellow artists' studios, discussions about art, shared meals, and the general camaraderie and occasional rivalries that characterized this close-knit group. He was known for his sociability within this circle, despite the often melancholic nature of his art. The Tenth Street Studio Building provided not just a place to work but also a vital network of support, criticism, and friendship.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

While McEntee's primary artistic focus remained the landscapes of the American Northeast, he did undertake several journeys that broadened his experiences, though they didn't fundamentally alter his core artistic vision.

In 1868-1869, he traveled to Europe, spending time in Italy, particularly Rome and Venice, and also visiting other art centers. This was a common pilgrimage for American artists of the era, offering opportunities to study Old Masters and experience European culture. During part of this trip, he was accompanied by Sanford Robinson Gifford. While in Rome, McEntee, Gifford, and Frederic Church, along with other American artists like William S. Haseltine and George Yewell, reportedly collaborated or were involved in discussions around works such as The Arch of Titus, a subject painted by several artists. McEntee's European experience, however, seems to have reinforced his appreciation for his native landscapes rather than leading him to adopt European subjects or styles wholesale.

Later in his career, he also made sketching trips to other parts of the United States, including a journey to Mexico. These excursions provided fresh material for his sketchbooks, but his finished paintings largely continued to explore the familiar themes and moods of his beloved Catskills and Hudson Valley. His heart, it seems, remained with the "gray November and leafless trees" of his home region.

The Diaries: A Chronicle of an Artist's Life

Perhaps one of Jervis McEntee's most enduring legacies, alongside his paintings, is the extensive diary he kept from 1872 until shortly before his death in 1891. These journals, now housed in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution, offer an extraordinarily rich and detailed account of an American artist's daily life, thoughts, struggles, and social interactions during the latter half of the 19th century.

McEntee was a diligent and candid diarist. He recorded his work in the studio, noting paintings started, in progress, and sold (or, often, not sold). He documented his financial anxieties, which were a recurring theme, reflecting the precarious nature of an artist's income even for established figures. He wrote about his sketching trips, the weather (a constant preoccupation for a landscape painter), his health, and his domestic life.

Crucially, the diaries are filled with observations about his fellow artists. He recounts visits with Church, Gifford, Whittredge, Kensett, Bierstadt, and many others, detailing their conversations, their new works, their successes, and their failures. He provides insights into the operations of the National Academy of Design, where he was elected an Associate in 1860 and a full Academician in 1861, and other art institutions like the Century Association. He also commented on art exhibitions, sales, and the changing tastes of patrons and critics.

The diaries reveal McEntee's personality: his loyalty to friends, his sensitivity, his occasional bouts of depression (especially after personal losses), his dry wit, and his keen observational skills. He noted humorous incidents, such as a near fire caused by children playing near a chimney, or peculiar encounters on trains. These personal touches make the diaries not just a historical document but a human one. They provide an invaluable primary source for art historians studying the Hudson River School, the New York art world of the Gilded Age, and the social and economic conditions faced by artists of that period.

Personal Life: Joys and Sorrows

Jervis McEntee's personal life was marked by both enduring companionship and profound loss. In 1854, he married Gertrude Sawyer, who was described as a vibrant and supportive partner. Their marriage appears to have been a happy one, and Gertrude was an integral part of his social and domestic life for nearly twenty-five years.

The diaries reflect a close family life. McEntee was connected to his siblings, including his sister Julia McEntee Dillon, whose husband was Calvert Vaux, the prominent landscape architect who co-designed Central Park with Frederick Law Olmsted. These family connections provided another layer of social and intellectual engagement.

A significant shadow was cast over McEntee's life by the death of his wife Gertrude in 1878. This loss affected him deeply, and his diary entries from this period and afterward reflect his grief and an increasing sense of solitude. Friends noted that he became more reserved and melancholic in his later years, a disposition that perhaps found a parallel in the somber beauty of his paintings.

Despite personal hardships and recurring financial concerns – he noted in 1862 having to return to his parents' home due to economic pressures before re-establishing himself in New York – McEntee persevered in his artistic pursuits. His dedication to his craft remained unwavering.

Later Years, Recognition, and Legacy

Jervis McEntee continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He was an active member of the National Academy of Design and participated in its annual exhibitions. His works were also shown at other prestigious venues, including the Paris Universal Exposition and the Royal Academy in London, indicating a degree of international recognition. He received a medal at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876.

However, by the late 19th century, the artistic tide was turning. The detailed realism and romantic nationalism of the Hudson River School were being supplanted by newer styles like Impressionism and Tonalism (though McEntee's work shares some affinities with the latter's emphasis on mood and atmosphere). While McEntee remained committed to his established style, the market for traditional Hudson River School landscapes began to wane. His diaries reflect his awareness of these changing tastes and his anxieties about his continued relevance.

Despite these shifts, McEntee continued to work diligently in his Tenth Street studio until illness forced him to return to his family home in Rondout. He died there on January 27, 1891, at the age of 62.

In the decades immediately following his death, McEntee, like many Hudson River School painters, faded somewhat from public and critical attention. However, the mid-20th century saw a resurgence of interest in 19th-century American art, and McEntee's contributions began to be re-evaluated. His unique focus on the melancholic aspects of nature, his poetic sensibility, and the extraordinary historical value of his diaries secured him a lasting place in American art history.

Today, Jervis McEntee's paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Art Institute of Chicago, and many others. His work is appreciated for its quiet beauty, its emotional depth, and its distinctive vision within the broader context of the Hudson River School. His diaries continue to be a vital resource for scholars, offering unparalleled insights into his life and times. He remains a testament to the power of an artist who, by focusing intently on a particular aspect of the natural world that resonated with his own temperament, created a body of work that is both deeply personal and enduringly evocative. His influence can be seen in later artists who explored themes of introspection and the more subdued moods of nature, and his meticulous chronicling of his era provides a foundation for understanding the artistic landscape of 19th-century America, a world populated by figures like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Robinson Gifford, Worthington Whittredge, Albert Bierstadt, John Frederick Kensett, George Inness, Winslow Homer, and Eastman Johnson, all of whom, in their own ways, shaped the course of American art.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of McEntee's Vision

Jervis McEntee's art offers a unique and valuable perspective within the Hudson River School. He was not a painter of grand, sunlit vistas or dramatic wilderness, but a poet of the quieter, more introspective moments in nature. His dedication to the "melancholy days" of autumn and the stark beauty of winter resulted in a body of work that is both consistent and deeply felt. His canvases invite contemplation, evoking a sense of nostalgia and a gentle sadness that speaks to the universal human experience of time's passage and the cyclical rhythms of the natural world.

Beyond his paintings, McEntee's meticulous diaries provide an invaluable historical record, offering a personal and detailed glimpse into the American art world of his time. Through his words and his art, Jervis McEntee emerges as a significant chronicler of his era – a dedicated artist, a loyal friend, and a sensitive observer of both the outer landscape and the inner emotional terrain. His legacy is one of quiet power, a testament to the enduring appeal of art that finds beauty in subtlety and depth in introspection.