Sanford Robinson Gifford stands as a pivotal figure in nineteenth-century American art, celebrated primarily as a landscape painter associated with the second generation of the Hudson River School. His unique contribution lies in his mastery of light and atmosphere, pushing the boundaries of landscape painting towards a style often categorized as Luminism. His works capture not just the topography of a scene, but its ephemeral mood, bathed in a soft, hazy light that became his signature. Born into a changing America, Gifford's art reflected both the nation's burgeoning pride in its natural scenery and a deeper, more poetic sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Sanford Robinson Gifford was born on July 10, 1823, in Greenfield, New York. He spent his formative years in Hudson, New York, a town nestled in the scenic Hudson River Valley that would profoundly influence his artistic vision. His family was relatively prosperous; his father, Elihu Gifford, co-owned and operated the Hudson Iron Works. While the family background might have suggested a future in industry or commerce, young Sanford harbored different aspirations.

He attended Brown University from 1842 to 1844, exploring classical studies. However, the pull towards art proved stronger. Leaving Brown without completing his degree, Gifford moved to New York City around 1845 to pursue formal art training. This was a crucial step, placing him in the heart of America's burgeoning art scene.

In New York, Gifford initially focused on figure painting. He studied drawing, perspective, and anatomy under the tutelage of John Rubens Smith, an English-born watercolorist and drawing master. He also attended anatomy lectures at the Crosby Street Medical College and took drawing classes at the prestigious National Academy of Design. This foundational training provided him with the technical skills necessary for his later, more specialized focus.

A decisive shift occurred in the summer of 1846. Gifford embarked on extensive sketching trips through the Catskill and Berkshire Mountains. These excursions into the wilderness of the American Northeast ignited a passion for landscape painting. Inspired by the works of the pioneering American landscape painter Thomas Cole, Gifford recognized the potential of the American landscape as a subject worthy of serious artistic exploration. He decided to dedicate himself primarily to landscape art, a path he would follow for the rest of his life.

The Hudson River School and the Rise of Luminism

By the late 1840s, Gifford was establishing himself within the New York art world. He became closely associated with the Hudson River School, a loosely knit group of painters inspired by the landscapes of the Hudson River Valley and surrounding areas, including the Catskills, Adirondacks, and White Mountains. This movement, initially led by figures like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, celebrated the American wilderness as a source of national identity and spiritual renewal.

Gifford is considered a leading figure of the second generation of the Hudson River School, alongside artists such as John Frederick Kensett and Frederic Edwin Church. While sharing the older generation's reverence for nature and detailed observation, these artists often explored different stylistic avenues. Gifford, in particular, became a key practitioner of what art historians later termed Luminism.

Luminism, emerging around the mid-nineteenth century, is characterized by its focus on the effects of light and atmosphere. Luminist paintings often depict calm, tranquil scenes, frequently featuring water or expansive skies. Brushstrokes are typically minimized, creating smooth surfaces that enhance the sense of stillness and contemplation. The light itself, often soft, hazy, and pervasive, becomes a primary subject, imbuing the landscape with a quiet, almost spiritual glow.

Gifford's approach to Luminism was distinctive. He excelled at rendering subtle atmospheric effects – the haze of Indian summer, the glow of twilight, the mist rising over water. His landscapes are rarely dramatic in the manner of Cole or Church; instead, they evoke a sense of serene poetry and quiet introspection. He achieved these effects through meticulous technique, often applying thin layers of paint and glazes to create delicate tonal transitions and a sense of depth and luminosity. His style began to mature in the early 1850s, reaching a recognized peak by the middle of that decade.

Travels Abroad: Broadening Horizons

Like many American artists of his time, Gifford felt the need to experience European art and landscapes firsthand. Travel became an essential part of his artistic development, enriching his palette, refining his technique, and broadening his subject matter. His first major trip abroad lasted from 1855 to 1857.

During this extensive tour, Gifford visited England, Scotland, France, the Low Countries, Germany, Switzerland, and, significantly, Italy. In Britain, he admired the works of the great landscape painter J.M.W. Turner, whose atmospheric effects and handling of light likely resonated with Gifford's own burgeoning interests. In Paris, he visited the studios of established artists and studied the Old Masters at the Louvre.

Italy, however, held a special allure. He spent considerable time there, sketching ancient ruins, picturesque countryside, and coastal scenes. The warm, golden light of the Italian landscape found its way into many of his subsequent paintings. Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples provided endless inspiration. During this period, he associated with other American and European artists, sharing experiences and ideas.

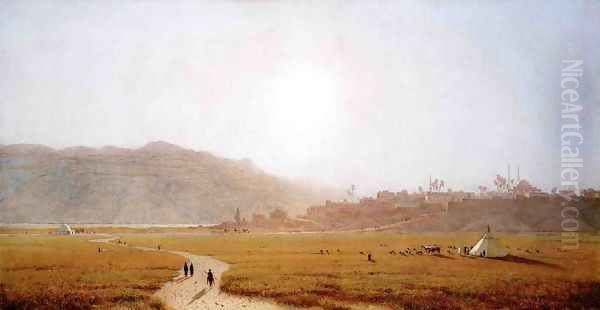

Gifford undertook a second major overseas journey more than a decade later, from 1868 to 1869. This trip took him again through Europe, but also further afield to the Near East, including Egypt and Syria. This experience added an exotic dimension to his work, resulting in paintings like Siout, Egypt. On parts of this journey, he traveled with fellow American painters Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge, strengthening his bonds within the artistic community. These travels provided him with a vast mental and visual library of landscapes, light effects, and compositions that he would draw upon for years to come.

The Civil War Years

The American Civil War (1861-1865) interrupted the lives and careers of many artists, including Gifford. A patriot, he enlisted in the Seventh Regiment of the New York State National Guard. This regiment, composed largely of men from prominent New York families, was called into federal service multiple times during the conflict.

Gifford served brief tours of duty in 1861, 1862, and 1863, primarily defending Washington D.C. and participating in the Gettysburg campaign aftermath. While his direct combat experience was limited, his time in the army camps and witnessing the realities of war undoubtedly affected him. Some art historians suggest that the war deepened the elegiac, sometimes melancholic, mood found in some of his paintings from the 1860s onwards. His wartime sketches provide a different perspective on his oeuvre, documenting camp life alongside his more typical landscape studies. Despite the interruption, he continued to paint, sometimes drawing inspiration from scenes witnessed during his service.

Mature Style and Masterworks

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, Gifford produced many of his most acclaimed works, solidifying his reputation as a master of Luminist landscape. His style continued to emphasize atmosphere over precise topographical detail, though his drawings and oil sketches reveal a keen observational skill. He sought to capture the feeling of a place, often bathed in the warm light of sunrise or sunset.

His technique involved careful layering. He often started with detailed pencil drawings or small oil sketches made outdoors. Back in his studio, he would compose the final painting, building up the surface with thin glazes of color to achieve the desired atmospheric haze and luminosity. This meticulous process resulted in paintings that seem to glow from within.

Several works stand out as representative of his mature style and are considered masterpieces of American art:

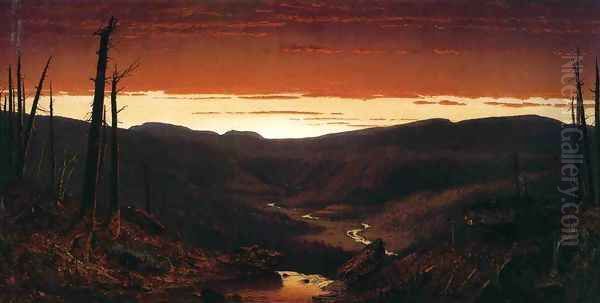

A Gorge in the Mountains (Kauterskill Clove) (1862): Often cited as one of his finest achievements, this painting depicts the dramatic Kauterskill Clove in the Catskills, a subject favored by Hudson River School artists. Gifford transforms the scene into a vision of sublime beauty, bathed in a hazy, golden light that softens the rugged terrain. It perfectly exemplifies his ability to blend detailed observation with poetic atmosphere. Contemporary critics hailed it as one of the greatest American landscapes ever painted.

Twilight in the Catskills (1862): This work is noted for its complex handling of color and light during the transitional moment of twilight. It reflects a shift towards exploring more nuanced and perhaps somber atmospheric effects, possibly influenced by his wartime experiences or simply a natural evolution of his style.

The Long Island Coast: While the exact date varies among versions, paintings with this title showcase Gifford's skill in depicting coastal scenes, capturing the interplay of light on water, sand, and hazy sky. These works often possess a profound sense of calm and spaciousness characteristic of Luminism.

Siout, Egypt (c. 1874, based on earlier sketches): Stemming from his Near Eastern travels, this painting demonstrates his ability to apply his signature style to non-American subjects. The exotic architecture and landscape are rendered with the same sensitivity to light and atmosphere found in his Hudson Valley scenes.

Mount Rainier, Bay of Tacoma, Puget Sound (1875): Representing his travels to the American West, this work captures the majestic scale of the western landscape while suffusing it with a soft, atmospheric light, linking the grandeur of the West with the poetic sensibility of his eastern scenes.

The Marshes of the Hudson (1878): A later work, this painting returns to his beloved Hudson River Valley. It depicts the expansive wetlands along the river, likely near his home, under a serene, light-filled sky. It is considered a major example of his late style, demonstrating his enduring commitment to capturing the subtle beauties of his native region.

These works, among many others, are housed in major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid.

Connections and Community: Life Among Artists

Gifford was an active and respected member of the New York art community. He maintained a studio for many years in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building, a hub for artists where he interacted daily with peers. His relationships with fellow painters were crucial to his personal and professional life.

His travels often involved companionships that fostered artistic exchange. His journeys with Albert Bierstadt, known for his dramatic Western landscapes, and Worthington Whittredge, another prominent landscape painter, provided opportunities for shared sketching and discussion. Whittredge later described Gifford as somewhat "mysterious," noting his tendency to disappear on long trips without notice and reappear seamlessly back into the art scene.

Gifford maintained a close friendship with Jervis McEntee, another Hudson River School painter known for his melancholic autumn landscapes. After Gifford's death, it was McEntee who meticulously cataloged the contents of Gifford's studio, creating an invaluable record of his known works. McEntee also penned a heartfelt memorial tribute to his friend.

He also knew Frederic Church, arguably the most famous landscape painter in America at the time. They encountered each other in Rome, and later, Gifford became involved alongside Church and others in debates concerning the direction of American art, particularly regarding the rise of younger artists trained in European figure painting traditions. This dialogue contributed to the formation of the Society of American Artists.

His interactions extended to figures like John F. Weir, a painter and the first director of the Yale School of Fine Arts, who delivered a moving eulogy praising Gifford's character and artistic contributions. Gifford's work was often compared to that of John Frederick Kensett, another master of Luminism, though critics noted Gifford's generally warmer palette and more overtly poetic approach. He also traveled with the lesser-known landscape painter Regis Gignoux on early European trips. Correspondence, such as letters exchanged with figures like William H. Henry (possibly William Henry Herriman, a collector and expatriate), reveals ongoing discussions about art and travel.

Gifford was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1851 and became a full Academician in 1854, cementing his status within the established art institution. He regularly exhibited his work at the Academy's annual exhibitions, as well as at venues like the Brooklyn Art Association and the Century Association, of which he was a long-standing member.

Critical Reception and Enduring Legacy

During his lifetime, Sanford Robinson Gifford enjoyed considerable success and critical acclaim. His paintings were sought after by collectors and consistently praised in the press for their beauty, poetry, and technical skill. Critics lauded his unique ability to capture the intangible qualities of light and air.

Reviewers often struggled to categorize his distinct style. Eugene Benson, a contemporary critic, described Gifford's work as achieving a "poetic realism," suggesting it transcended mere imitation of nature to capture its essence. John F. Weir spoke of Gifford's ability to make nature "transparent," revealing its inner spirit through the masterful handling of light. His paintings were seen as embodying a refined, contemplative approach to the American landscape.

His exhibitions were significant events. The display of A Gorge in the Mountains (Kauterskill Clove) at the Tenth Street Studio Building exhibition in 1862 was met with widespread admiration. His participation in international exhibitions, such as the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867, helped introduce his work to European audiences.

Following his untimely death, the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized a major memorial exhibition in 1880-1881, featuring 160 of his paintings. This exhibition, accompanied by a catalog compiled with the help of Jervis McEntee and John F. Weir, solidified his reputation and provided a comprehensive overview of his career.

While the popularity of the Hudson River School declined in the early 20th century with the rise of modernism, Gifford's work, along with that of other Luminist painters, experienced a significant revival of interest starting in the mid-20th century. Today, he is recognized as one of the most accomplished and distinctive painters of his generation. His sensitive renderings of light and atmosphere continue to resonate with viewers, offering moments of quiet contemplation and appreciation for the subtle beauties of the natural world. His legacy lies in his unique contribution to American landscape painting, pushing beyond mere representation to evoke mood, poetry, and the ethereal effects of light.

Later Years and Death

In his later years, Gifford continued to paint, often returning to familiar subjects in the Catskills and along the Hudson River. He maintained his studio in New York City but spent considerable time in Hudson, New York, drawing inspiration from the landscapes of his youth. Friends described him as gentlemanly, cultured, and dedicated to his art.

His life was cut short unexpectedly. In the summer of 1880, while on a trip to Lake Superior, he contracted malarial fever. He returned to New York City but failed to recover. Sanford Robinson Gifford died on August 29, 1880, at the age of 57. His death was mourned by the American art community, who recognized the loss of a unique talent and a cherished colleague.

Conclusion

Sanford Robinson Gifford carved a unique niche within the broader movement of the Hudson River School. More than just a recorder of American scenery, he was a poet of light, air, and mood. Through his distinctive Luminist style, he captured the ephemeral qualities of the natural world, imbuing his landscapes with a sense of tranquility and quiet wonder. His extensive travels enriched his art, but he remained deeply connected to the landscapes of the American Northeast. His friendships and interactions within the vibrant art scene of 19th-century New York further shaped his career. Remembered through masterpieces like A Gorge in the Mountains and The Marshes of the Hudson, Gifford's legacy endures, his paintings celebrated for their technical brilliance and their profound, atmospheric beauty. He remains a key figure for understanding the development of American landscape painting and the subtle, evocative power of Luminism.