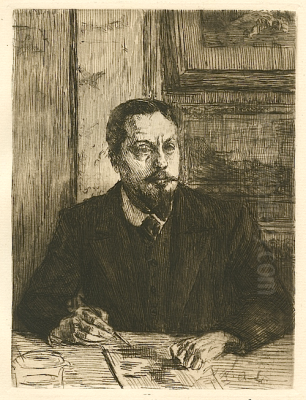

Alexandre Lunois stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the vibrant Parisian art scene of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A French artist born on February 2, 1863, and passing on September 2, 1916, Lunois carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a printmaker, excelling in engraving and, most notably, lithography. His professional journey was marked by a profound engagement with diverse cultural landscapes, gleaned from extensive travels, which deeply informed his artistic output. While rooted in Paris, his artistic vision was broadened by experiences in Spain, Morocco, Algeria, and Belgium, infusing his work with a unique blend of Parisian modernity and exotic allure. Lunois's art predominantly aligns with Impressionist sensibilities in its capture of fleeting moments and atmospheric light, yet it also frequently touches upon Symbolist themes, delving into the evocative and the enigmatic. His oeuvre spans a rich tapestry of subjects, from the natural world and scenes of everyday life to captivating Orientalist compositions.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the artistic crucible of Paris, Alexandre Lunois was immersed in a milieu teeming with creative energy from a young age. This environment undoubtedly nurtured his innate talents, leading him to develop an early interest in drawing, painting, and sculpture. Unlike many of his contemporaries who followed a traditional academic path through the École des Beaux-Arts, Lunois's artistic development was largely self-directed, a testament to his independent spirit and dedication.

His initial foray into the professional art world saw him engaged in commercial lithographic printing. This practical grounding provided him with an intimate understanding of the medium's technical intricacies. It was during this period that he began to experiment and push the boundaries of traditional lithography. His early works often consisted of black and white lithographs, showcasing a keen observational skill and a burgeoning personal style. Pieces from this era, such as those depicting Parisian Life Scenes or the dynamic energy of The Circus, already hinted at his ability to capture the essence of his subjects with vivacity and insight. He also produced evocative Dutch Landscapes, reflecting early travels or an interest in the Dutch Golden Age masters.

The Innovator of "Lavage Lithographique"

Alexandre Lunois is widely celebrated, and rightly so, as a pivotal innovator in the field of lithography. He is often credited as the "reinventor of the lithographic technique," a significant claim that underscores his contribution to the medium. His most notable innovation was the development and mastery of what he termed "lavage lithographique," or lithographic wash. This technique allowed him to achieve painterly effects on the lithographic stone, creating subtle gradations of tone, rich textures, and a sense of fluidity that was revolutionary for its time.

The "lavage lithographique" enabled Lunois to imbue his prints with a dreamlike quality and a remarkable depth of color, particularly as he transitioned from monochromatic to color lithography. This shift was transformative, allowing his artistic expression to flourish with newfound vibrancy and emotional resonance. The technique involved applying ink washes directly onto the stone, much like a watercolorist uses washes on paper, which, when printed, resulted in soft, atmospheric effects that were difficult to achieve with traditional crayon or pen methods on stone. This mastery distinguished him from many of his contemporaries and aligned his prints more closely with the expressive potential of painting. His technical prowess was not merely for show; it was always in service of his artistic vision, allowing for a more direct and emotive translation of his perceptions onto the printed page.

Travels and the Embrace of Orientalism

Travel was a cornerstone of Alexandre Lunois's artistic life and a profound source of inspiration. His journeys took him beyond the familiar landscapes of France to Spain, Morocco, Algeria, and Belgium. Each destination left an indelible mark on his artistic sensibilities, enriching his palette, his subject matter, and his understanding of different cultures.

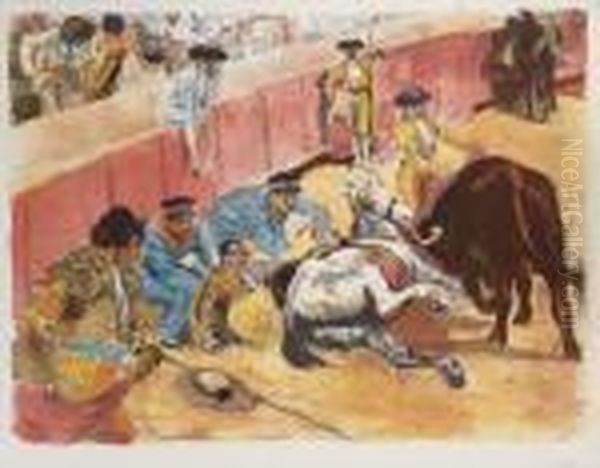

Spain, with its dramatic landscapes, vibrant traditions, and the powerful legacy of artists like Francisco Goya, particularly captivated Lunois. His Spanish-themed works, such as the iconic lithograph La Corrida (The Bullfight), Nuit de Sainte-Anne (Night of Saint Anne), and Nuit à Séville (Night in Seville), are imbued with the passion, color, and drama of Spanish life. He masterfully captured the intensity of the bullfight, the atmospheric charm of nocturnal scenes, and the distinct character of the Spanish people. These works often showcase his innovative wash technique to great effect, conveying the heat, dust, and emotion of the Iberian Peninsula.

His travels to Morocco and Algeria further expanded his artistic horizons, leading to a significant body of Orientalist work. Unlike some of his contemporaries whose Orientalism could be superficial or overly romanticized, Lunois approached these cultures with a keen eye for detail and a sense of genuine engagement. Works like Arab Woman with Veil and Weaver Woman of Morocco demonstrate his ability to depict the dignity and daily life of his subjects with sensitivity. The strong North African light, the vibrant textiles, and the unique architectural forms provided him with rich visual material that he translated into compelling and atmospheric prints. His time in Volendam, a fishing village in the Netherlands, also resulted in notable pieces like The Dutch Girl of Volendam, showcasing his versatility in capturing diverse local characters and environments.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Representative Works

Alexandre Lunois's artistic style is characterized by a harmonious blend of Impressionistic observation and Symbolist undertones. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, a hallmark of Impressionism, evident in his landscapes and cityscapes. His figures are often rendered with a sense of immediacy and naturalism. However, his work also frequently transcends mere representation, evoking moods, emotions, and a sense of mystery that aligns with Symbolist aims. His use of color became increasingly bold and expressive, particularly in his color lithographs, where he exploited the medium's potential for rich, nuanced hues.

His thematic concerns were broad. Parisian life, with its cafes, theaters, and street scenes, provided endless inspiration, as seen in early works like Parisian Life Scenes. The world of entertainment, particularly The Circus, allowed him to explore movement, light, and spectacle. His travels, as discussed, opened up new vistas, leading to his celebrated Spanish and Orientalist works. He also produced illustrations, notably for a collection of Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales, demonstrating his ability to adapt his style to narrative and imaginative subjects.

Beyond the already mentioned La Corrida, Nuit à Séville, and his Orientalist pieces, other works further illustrate his range. His depictions of dancers, musicians, and everyday people are rendered with an empathetic eye. The quality of his line, whether in etching or lithography, is consistently strong and expressive, and his compositions are thoughtfully constructed to draw the viewer in. His innovative "lavage lithographique" technique is perhaps most evident in works where subtle tonal shifts and atmospheric effects are paramount, lending a unique softness and depth that distinguishes his prints.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Artistic Milieu

Alexandre Lunois operated within a rich and dynamic artistic milieu in late 19th and early 20th century Paris, a period of intense experimentation and the flourishing of various modern art movements. While largely self-taught, he was not an isolated figure. He absorbed influences from various sources and interacted with many prominent artists of his time.

Early in his career, Lunois briefly studied in the workshop of Achille Sirouy, a known lithographer, which likely provided him with foundational technical skills. He also reportedly sought guidance from Henri Fantin-Latour, a master renowned for his sensitive portraits and delicate floral still lifes, but also a distinguished lithographer himself. Fantin-Latour's own explorations in transfer lithography and his subtle tonal work may have offered valuable lessons for Lunois.

The influence of earlier masters is also discernible. The dramatic intensity and social commentary in the prints of Francisco Goya undoubtedly resonated with Lunois, especially during his time in Spain. The realism and bold compositions of Édouard Manet, who himself was a significant printmaker, also likely informed Lunois's approach to modern life subjects. The rich colors and imaginative compositions of Gustave Moreau, a leading Symbolist painter, may have influenced the more evocative and dreamlike qualities in some of Lunois's works. His interest in Dutch art is evidenced by his admiration for artists like Frans Hals, Jan Vermeer van Delft, and Adriaen van Ostade, whose mastery of light, character, and everyday scenes likely inspired his technical explorations in lithography to achieve similar richness.

Among his contemporaries, Lunois's work can be situated alongside that of other artists exploring the expressive potential of printmaking. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec revolutionized poster art and color lithography with his dynamic depictions of Parisian nightlife. While Lunois's style was generally less stylized and more painterly than Lautrec's bold, graphic approach, both artists shared a fascination with the spectacle of modern urban life and pushed the boundaries of color lithography. Lunois's achievements in color and technique were significant, even if Lautrec achieved wider popular fame.

The Nabis group, including artists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, were also deeply engaged with color lithography, often creating intimate, decorative scenes. Lunois's work, while distinct, shares with the Nabis an interest in the expressive power of color and pattern. Printmakers like Félix Vallotton, known for his striking black-and-white woodcuts and later his paintings, acknowledged Lunois's impact. Vallotton himself was a master of graphic simplification and strong contrasts, offering a different but complementary approach to printmaking.

Other Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters who also made significant contributions to printmaking include Edgar Degas, with his experimental monotypes and etchings capturing dancers and modern life, and Camille Pissarro, who produced a substantial body of etchings and lithographs depicting rural and urban scenes. The broader artistic currents of Japonisme, the influence of Japanese prints which captivated artists like Mary Cassatt and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (himself a master etcher), also played a role in the revival of printmaking as an original art form, emphasizing bold compositions, flat areas of color, and everyday subjects, elements that can be subtly discerned in the broader printmaking ethos of the era from which Lunois benefited and to which he contributed. Even the expressive color and emotional intensity of Vincent van Gogh or the Symbolist explorations of Paul Gauguin (who also experimented with prints) formed part of the rich artistic tapestry of the time, pushing boundaries of color and form that indirectly created a fertile ground for innovations like Lunois's.

Recognition, Character, and Legacy

Alexandre Lunois's contributions to the arts, particularly in the realm of lithography, did not go unnoticed during his lifetime. He received several official accolades, which underscored his standing in the French art world. Notably, he was selected as a jury member for the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, a prestigious honor indicating the respect he commanded among his peers. In 1902, his achievements were further recognized when he was awarded the "Ruban Rouge," signifying his induction into the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian distinctions. His works were exhibited in France and internationally, and many found their way into significant public collections, including the esteemed print room of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Beyond his artistic achievements, Lunois was known for his independent spirit, passion, and a certain joie de vivre. His works sometimes reveal a subtle sense of humor or a gentle satirical touch, reflecting a keen observation of human nature and societal quirks. He was not only a visual artist but also a writer and poet, publishing several books on art and poetry, which suggests a multifaceted intellectual and creative personality. Despite his successes, Lunois reportedly faced periods of financial difficulty, a common plight for many artists who prioritized their creative vision over commercial demands. Nevertheless, he remained driven by his passion and a sincere dedication to his artistic ideals.

Alexandre Lunois passed away in Paris on September 2, 1916, at the relatively young age of 53. His legacy, however, endures primarily through his innovative contributions to lithography. His development of the "lavage lithographique" technique significantly expanded the expressive possibilities of the medium, allowing for painterly effects and atmospheric subtleties that were previously challenging to achieve in print. He demonstrated that lithography could be a powerful medium for original artistic expression, on par with painting or drawing.

His diverse subject matter, from the bustling streets of Paris to the sun-drenched landscapes of Spain and Morocco, provides a rich visual record of his time and his travels. His ability to capture the essence of different cultures with sensitivity and insight remains commendable. Today, his works are sought after by collectors and are studied for their technical mastery and artistic merit. Alexandre Lunois remains an important figure for understanding the evolution of printmaking at the turn of the twentieth century, a dedicated artist who skillfully blended technical innovation with a deeply personal and evocative vision of the world around him. His influence, though perhaps not as widely trumpeted as some of his more famous contemporaries, was nonetheless significant for fellow printmakers and for the elevation of lithography as a fine art form.