Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) stands as a colossus in the world of 20th-century Japanese art. A painter and printmaker of exceptional skill and vision, he is celebrated primarily for his breathtaking landscape prints, which masterfully blend Western realism with traditional Japanese aesthetics and techniques. His life spanned periods of immense change in Japan, from the Meiji Restoration's embrace of Western ideas to the turbulent years surrounding World War II. Throughout this, Yoshida remained a dedicated artist, an intrepid traveler, and a key figure in the Shin-hanga (New Prints) movement, leaving behind a legacy that continues to captivate audiences worldwide. His work serves not only as a visual record of the places he visited but also as a testament to the possibilities of cross-cultural artistic dialogue.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born Ueda Hiroshi on September 19, 1876, in the city of Kurume, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan, the artist's destiny took a decisive turn early in life. He showed a natural aptitude for art, an inclination nurtured by his adoptive father, Yoshida Kasaburo, who was a public school art teacher. This adoption at the age of 19 not only gave him the name Yoshida Hiroshi, by which he would become famous, but also provided a supportive environment for his burgeoning artistic talents. His early training was rooted in the Western-style painting traditions that were gaining prominence in Meiji-era Japan.

Seeking formal instruction, Yoshida initially moved to Kyoto, a city steeped in traditional arts but also experiencing the influx of new ideas. There, he studied under Tamura Shoryu, a noted teacher of Western-style painting. However, his ambition soon led him to Tokyo, the nation's rapidly modernizing capital and burgeoning art center. In Tokyo, he further honed his skills under Koyama Shōtarō, another influential teacher of Western painting (Yōga). Koyama was himself a student of Kawakami Tōgai, one of the pioneers who introduced Western techniques to Japan, and later founded the Fudo-sha, a private painting school where Yoshida continued his studies.

During these formative years, Yoshida primarily worked in oils and watercolors. He quickly gained recognition for his talent in these mediums, associating with prominent artists and becoming a member of the Meiji Fine Arts Society. He later helped establish the Pacific Painting Society (Taiheiyō-Gakai) in 1902, alongside other young artists eager to promote Western-style art in Japan. His early work demonstrated a keen observational skill and a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, traits that would become hallmarks of his later printmaking career. His path mirrored that of other Yōga pioneers like Kuroda Seiki, who studied in Europe and brought back Impressionist influences.

Embracing the World: Travels and International Acclaim

Yoshida's artistic vision was never confined to the shores of Japan. A defining characteristic of his career was his extensive travel, which began remarkably early. In 1899, at the age of just 23, he made his first trip to the United States, accompanied by his friend Nakagawa Hachirō. They held an exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts (then the Detroit Museum of Art), followed by successful shows in Boston, Washington D.C., Providence, and later, Europe. These early international exhibitions were crucial, exposing his work to Western audiences and establishing his reputation abroad long before he became known for his woodblock prints.

These journeys were not mere sightseeing tours; they were expeditions for artistic inspiration and learning. Yoshida was fascinated by the diverse landscapes and cultures he encountered. He sketched and painted prolifically, capturing scenes from the majestic Grand Canyon and Yosemite National Park in the United States, the rugged beauty of the Swiss Alps, the historic canals of Venice, the ancient wonders of Egypt, the vibrant streets and iconic landmarks of India like the Taj Mahal, and scenes from China and Korea. His travels provided him with a vast repository of subjects that distinguished his work from many contemporaries who focused solely on Japanese themes.

His success in the West was significant. His watercolors and oil paintings sold well, providing him with the financial means to continue his travels and artistic pursuits. He interacted with Western artists and collectors, gaining insights into different artistic perspectives. Figures like the influential American collector of Asian art, Charles Lang Freer, were active during this period, fostering an American appreciation for Japanese aesthetics, a climate Yoshida benefited from. His international experiences undoubtedly deepened his understanding of Western artistic principles, particularly realism, perspective, and the effects of light, which he would later integrate seamlessly into his printmaking.

The Turn to Woodblock Prints: The Shin-hanga Movement

Despite his success as a painter in the Western style, Yoshida's artistic journey took a pivotal turn towards woodblock printing around 1920. This shift occurred within the context of the Shin-hanga (New Prints) movement, which aimed to revitalize the traditional Japanese art of ukiyo-e woodblock printing that had declined in the late 19th century. Ukiyo-e, famed for masters like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige, had captivated Western artists but faced challenges domestically due to the rise of new technologies like photography and lithography.

The Shin-hanga movement, largely spearheaded by the visionary publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō, sought to combine the traditional collaborative system of ukiyo-e (involving an artist, carver, printer, and publisher) with modern aesthetics and subjects that appealed to both Japanese and Western tastes. These prints often featured romanticized landscapes, beautiful women (bijin-ga), and actor portraits, rendered with a greater degree of realism and atmospheric depth than many older ukiyo-e. Key artists associated with Watanabe and the Shin-hanga movement include Kawase Hasui, renowned for his nostalgic landscapes, Itō Shinsui, famous for his depictions of beautiful women, and Hashiguchi Goyō, whose brief career produced exquisite prints.

Yoshida initially collaborated with Watanabe, producing seven prints starting in 1920. However, his experience was profoundly impacted by the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, which destroyed Watanabe's workshop and Yoshida's earlier blocks. Following a trip to the US to raise funds and exhibit, Yoshida made a crucial decision upon his return in 1925: he would establish his own printmaking workshop. This move set him apart from most Shin-hanga artists who remained reliant on publishers like Watanabe.

Forging His Own Path: The Yoshida Studio

The establishment of the Yoshida Studio in 1925 marked a new phase in Hiroshi Yoshida's career, one defined by artistic independence and rigorous quality control. Unlike the traditional ukiyo-e and standard Shin-hanga model where the artist typically only provided the design, Yoshida took an unusually hands-on approach. He not only designed his prints but also actively participated in and supervised the carving of the woodblocks and the complex printing process. He hired his own team of skilled carvers and printers, ensuring that the final product precisely matched his artistic vision.

This level of involvement blurred the lines between the collaborative Shin-hanga and the burgeoning Sōsaku-hanga (Creative Prints) movement, where artists like Onchi Kōshirō, Yamamoto Kanae, and Hiratsuka Un'ichi advocated for the artist to handle every stage of production – designing, carving, and printing – to ensure complete personal expression. While Yoshida maintained a division of labor by employing artisans, his deep engagement in the technical aspects and his insistence on final approval aligned him spiritually with the Sōsaku-hanga ideal of the artist as the ultimate creator.

To signify his personal supervision and approval of prints produced under his exacting standards, Yoshida often used the jizuri ("self-printed") seal on the margins of his prints, particularly on early impressions. His prints also typically bear his signature in pencil in the Roman alphabet, alongside his name and seal printed within the image area in Japanese. This meticulous approach ensured a consistently high quality and allowed him to experiment extensively with color and impression techniques to achieve the subtle effects he desired. His studio became a hub of activity, producing hundreds of distinct print designs over the next quarter-century.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Hiroshi Yoshida's mature artistic style is a remarkable synthesis of Eastern and Western traditions. From his Western training, he incorporated principles of linear perspective, realistic depiction of form, and a profound understanding of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). From his Japanese heritage, he drew upon the compositional elegance, flattened perspectives in certain works, decorative sense, and, most importantly, the sophisticated techniques of multi-block color woodblock printing.

His mastery of the woodblock medium was extraordinary. Yoshida was known for his meticulous attention to detail and his innovative approach to achieving specific effects. He understood that the key to capturing the nuances of atmosphere – mist, haze, water reflections, the glow of dawn or dusk – lay in the subtle layering of colors. A single Yoshida print might require numerous woodblocks, one for each distinct color or tone, and could involve dozens of separate impressions (applications of color) onto the fine Japanese washi paper. Some of his more complex prints reportedly involved over 50 impressions and utilized up to 30 carved blocks.

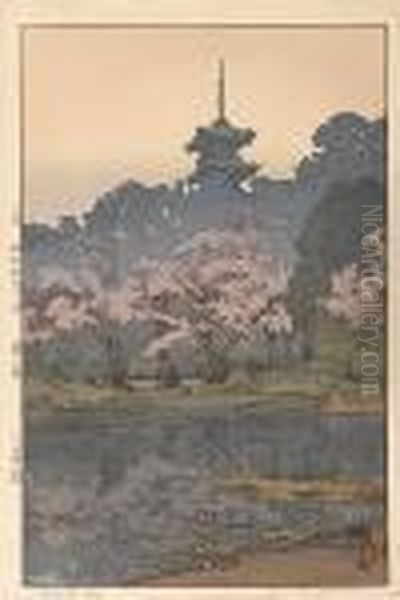

He was particularly adept at using the traditional bokashi technique, a method of achieving smooth gradations of color by carefully wiping the pigment on the block before printing. This allowed him to render realistic skies, water surfaces, and the soft diffusion of light. Yoshida often created multiple versions of the same scene under different lighting conditions or at different times of day, much like the French Impressionist Claude Monet did with his series paintings of haystacks or Rouen Cathedral. Yoshida's "Sailing Boats" series, for instance, depicts the same view in morning, afternoon, and evening light, showcasing his fascination with transient atmospheric effects. His ability to convey the quality of light, whether the crisp clarity of alpine air or the humid haze of India, remains one of the most admired aspects of his work, often evoking comparisons to the atmospheric landscapes of J.M.W. Turner.

A World of Subjects: Representative Works and Themes

Yoshida's oeuvre is vast and diverse, reflecting his extensive travels and his deep appreciation for the natural world. While he created stunning depictions of his native Japan, a significant portion of his work features international landscapes, setting him apart from many Shin-hanga contemporaries like Kawase Hasui who focused primarily on Japanese scenes.

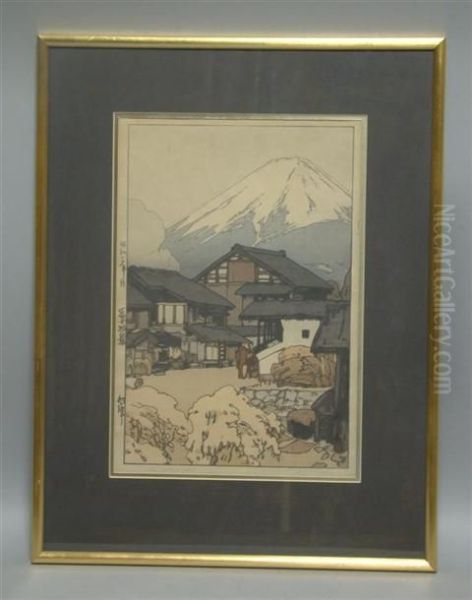

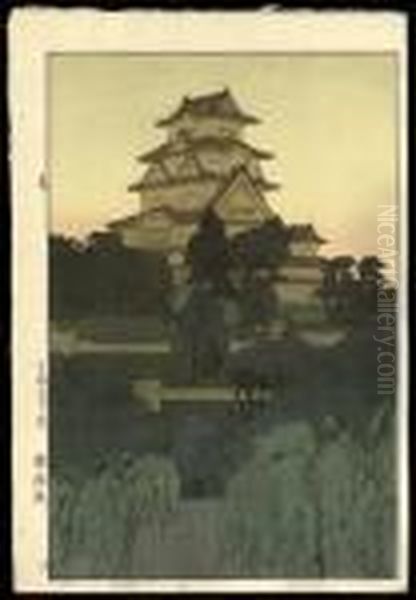

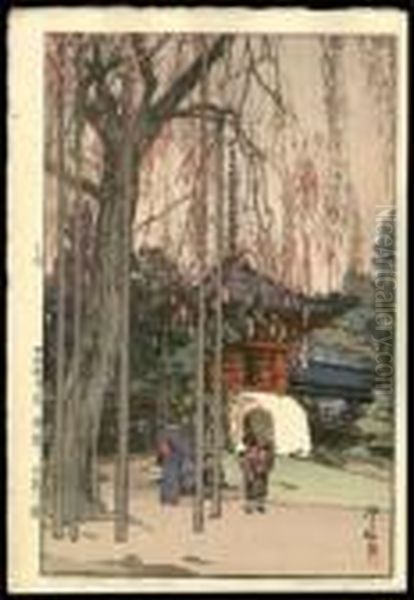

His Japanese subjects include iconic landmarks and serene natural settings. Mount Fuji, the spiritual heart of Japan, appears frequently, captured from various viewpoints and in different seasons, such as in "Fuji from Funatsu." He depicted famous castles like in "Himeji Castle, Evening," tranquil temple gardens, bustling city scenes, and the picturesque Inland Sea. Works like "The Cherry Tree in Kawagoe," part of an "Eight Scenes of Cherry Blossoms" series, exemplify his ability to capture the delicate beauty of Japanese flora. He was also an avid mountaineer, and his love for the mountains is evident in his depictions of the Japanese Alps. In later life, he founded the Japan Mountain Painting Association (Nihon Sangaku Gakai), further emphasizing this passion.

His international prints are equally compelling. The "Indian and Southeast Asian" series includes masterpieces like the various views of the "Taj Mahal" (e.g., "Taj Mahal, Morning," "Taj Mahal Garden (Day)"), capturing the monument's ethereal beauty in changing light. His American series features dramatic renderings of the Grand Canyon, Yosemite's "El Capitan," Mount Rainier, and Yellowstone. European subjects include the Swiss Alps ("Jungfrau"), Venice, the Acropolis in Athens, and even the Sphinx in Egypt. These works demonstrate his remarkable ability to adapt his style and technique to convey the unique character and atmosphere of diverse global landscapes. Other notable works showcasing his skill include "Glittering Sea" from his Inland Sea series, known for its masterful depiction of light on water, and prints like "Seishi, 1940" depicting scenes in China.

Interactions and Influence

Throughout his career, Yoshida was actively involved in the Japanese art world. His role in founding the Pacific Painting Society (Taiheiyō-Gakai) early in his career demonstrated his commitment to promoting new artistic trends. His later establishment of the Japan Mountain Painting Association reflected his personal passion and provided a platform for artists specializing in alpine subjects. He was a respected figure, known for his strong opinions and his dedication to artistic quality.

While he operated his own studio, he remained connected to the broader art scene. His international travels brought him into contact with artists and collectors abroad, fostering cross-cultural exchange. While specific documented interactions with Western artists like Helen Hyde or Bertha Lum (American printmakers also working in Japan) are less detailed, his presence and success in international exhibitions undoubtedly placed him within the global conversation about modern printmaking. His relationship with publishers like Watanabe Shōzaburō, though brief, connected him to the core of the Shin-hanga movement and artists like Hasui and Shinsui.

Yoshida's influence extended significantly through his family. His wife, Fujio Yoshida (née Kajiwara), was also an accomplished artist. Their eldest son, Toshi Yoshida (1911-1995), became a renowned printmaker in his own right, initially working in his father's style before developing his own abstract and figurative modes. Toshi played a crucial role in promoting his father's work and continuing the family's artistic legacy internationally. Another son, Hodaka Yoshida (1926-1995), also became a prominent modern artist. The Yoshida family legacy continues with subsequent generations, making it a remarkable multi-generational artistic dynasty.

Legacy and Contemporary Evaluation

Hiroshi Yoshida's legacy is multifaceted and enduring. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest artists of the Shin-hanga movement, even as his independent production methods set him somewhat apart. His technical mastery of the woodblock medium is virtually unparalleled in the 20th century. His ability to synthesize Western realism with Japanese aesthetics created a unique and highly appealing style that resonated with audiences both in Japan and internationally.

His works are praised for their exquisite detail, sophisticated color harmonies, and masterful rendering of light and atmosphere. They evoke a sense of tranquility, grandeur, and profound respect for the natural world. Yoshida successfully elevated landscape printmaking to a high art form, capturing not just the appearance of a place but also its mood and essence. His prints remain highly sought after by collectors and are held in prestigious museum collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum, the Toledo Museum of Art (which holds a significant collection), and the Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art.

Contemporary evaluation recognizes Yoshida not only for his artistic skill but also for his role as a cultural bridge between Japan and the West. His extensive travels and his depiction of global subjects introduced international landscapes to Japanese audiences and showcased Japanese artistic techniques to the world. He demonstrated that traditional methods could be adapted to modern sensibilities and diverse subject matter. His dedication to quality and his independent spirit continue to inspire printmakers today. Although he passed away on April 5, 1950, at the age of 74, before completing a planned "One Hundred Views" series, the 259 woodblock prints he created during his lifetime form a monumental contribution to modern Japanese art.

Conclusion

Hiroshi Yoshida was more than just a skilled technician or a prolific artist; he was a visionary who navigated the complex artistic currents of his time with remarkable clarity and purpose. Starting as a painter trained in Western methods, he embraced the traditional Japanese woodblock medium, transforming it through his unique perspective and demanding standards. His extensive travels informed a body of work that is both globally expansive and deeply personal, characterized by its technical brilliance, atmospheric depth, and serene beauty. As a key figure in the Shin-hanga movement and the founder of his own influential studio, Yoshida played a crucial role in shaping the course of modern Japanese printmaking. His legacy endures not only in his beautiful prints but also in the ongoing appreciation for the rich dialogue possible between different artistic traditions, a dialogue he mastered with unparalleled elegance.