Introduction: An Artist of Light and Landscape

Alexis Auguste Delahogue stands as a significant figure within the French Orientalist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Soissons, France, in 1867 and passing away in Nice in 1936, Delahogue dedicated much of his artistic career to capturing the unique landscapes, vibrant light, and daily life of North Africa, particularly Algeria and Tunisia. Working alongside his twin brother, Eugène Delahogue, he developed a distinctive style characterized by luminous palettes, keen observation, and an ability to convey the atmosphere of the Maghreb. His work, often associated with Post-Impressionist sensibilities in its handling of color and light, provides a fascinating window into the European artistic engagement with the "Orient" during a period of colonial expansion and intense cultural curiosity.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

The latter half of the nineteenth century in France was a period of immense artistic ferment. The established academic traditions, championed by artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, were being challenged by successive waves of innovation, from the Realism of Gustave Courbet to the revolutionary light-filled canvases of Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and the subsequent explorations of Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin. It was into this dynamic environment that Alexis Auguste Delahogue and his twin brother Eugène were born in 1867.

While specific details about Delahogue's formal artistic training remain somewhat scarce in readily available records, it is highly probable that he received instruction within the French academic system, perhaps at a regional school or under a private tutor, before potentially gravitating towards the ateliers of Paris. The emphasis on drawing, composition, and the study of Old Masters was standard. However, his mature style clearly indicates an absorption of more contemporary influences, particularly the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of natural light, and the expressive potential of color. His path reflects a common trajectory for artists of his generation: grounding in traditional techniques followed by an embrace of modern approaches to seeing and painting.

The Journey South: Embracing Orientalism

A defining aspect of Alexis Auguste Delahogue's career was his deep engagement with North Africa. Alongside his brother Eugène, he undertook extensive travels, immersing himself in the landscapes and cultures of Algeria and Tunisia. This journey south was part of a broader phenomenon known as Orientalism, where European artists, writers, and scholars turned their gaze towards the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. This fascination was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel opportunities, romantic notions of the exotic, and a desire to escape the perceived constraints and industrialization of European society.

Delahogue was captivated by the unique quality of light in the Maghreb – the intense, clear sunlight that bleached the desert landscapes and cast sharp, dramatic shadows. His paintings frequently depict the vast expanses of the Sahara, the winding streets of ancient cities like Algiers and Constantine, the tranquil beauty of oases such as Biskra and El Kantara, and the timeless spectacle of camel caravans traversing the dunes. Unlike some Orientalists who focused on historical reconstructions or highly dramatized harem scenes, Delahogue's work often emphasizes the landscape itself and the atmospheric conditions, populated by figures that seem integral to their environment rather than mere exotic props.

His travels provided a rich repository of subjects. He observed the daily rhythms of life, the architecture adapted to the climate, and the interplay between human activity and the powerful natural surroundings. This direct experience lent an authenticity to his work, even as it was inevitably filtered through a European artistic sensibility. He sought to translate the sensory experience – the heat, the light, the colors – onto canvas.

Artistic Style: Light, Color, and Atmosphere

Alexis Auguste Delahogue's style is often characterized by its vibrant palette and sensitivity to light. While grounded in realistic observation, his application of paint and use of color show affinities with Post-Impressionism. He wasn't afraid to use bold hues to convey the intensity of the North African sun or the cool transparency of shadows. His brushwork could be varied, sometimes detailed and precise, other times looser and more suggestive, capturing the shimmering effects of heat haze or the texture of sand and stone.

He demonstrated a remarkable ability to differentiate the subtle variations in light throughout the day – the cool blues and purples of dawn, the brilliant yellows and oranges of midday, and the warm, elongated shadows of late afternoon. Water, whether in an oasis pool or the distant Mediterranean, often features as a reflective surface, adding another layer of luminosity to his compositions. His focus was less on minute ethnographic detail, unlike contemporaries such as Ludwig Deutsch or Rudolf Ernst, and more on the overall mood and visual impact of the scene.

His compositions are typically well-structured, often using strong diagonal lines, such as the path of a caravan or the slope of a dune, to lead the viewer's eye into the scene. He balanced areas of intense detail with broader, more simplified passages, creating a sense of both immediacy and expansive space. The human element, while present, is often integrated into the larger landscape, emphasizing the scale and power of nature in the desert environment.

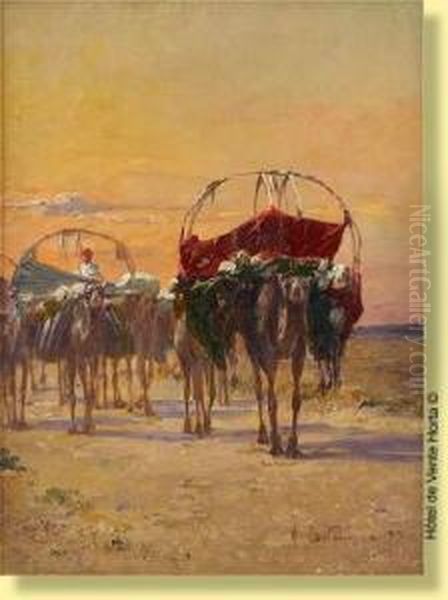

Representative Works: Visions of North Africa

Several paintings stand out as representative of Delahogue's oeuvre. Le Caravan dans le Désert (The Caravan in the Desert) is perhaps one of his most iconic themes, revisited in various compositions. These works typically depict a line of camels and figures progressing across an immense, sun-drenched desert landscape. Delahogue masterfully captures the rhythmic movement of the caravan, the textures of sand under a vast sky, and the palpable sense of heat and distance. The play of light on the figures and animals, and the long shadows cast across the dunes, are rendered with characteristic sensitivity.

Another notable work, sometimes titled Szene in Tunis (Scene in Tunis), showcases his ability to depict urban environments. These paintings often focus on marketplaces, street scenes, or architectural studies, capturing the interplay of light and shadow in narrow alleyways or sunlit courtyards. He rendered the textures of whitewashed walls, colorful textiles, and the activity of local inhabitants with an eye for atmospheric effect. These works provide a glimpse into the daily life observed during his travels, portrayed with his signature luminous palette.

Other typical subjects include views of specific locations like the gorges of El Kantara or the palm groves of Biskra, often celebrated by other Orientalist painters like Gustave Guillaumet and Étienne Dinet. In these landscapes, Delahogue explored the contrast between the arid desert and the lush vegetation of oases, again focusing on the effects of light on different surfaces and colors.

The Delahogue Brothers: A Unique Collaboration

The artistic journey of Alexis Auguste Delahogue is inseparable from that of his twin brother, Eugène Delahogue (1867-1930). They shared not only a birth year but also a profound artistic affinity and a passion for North African subjects. They traveled together, sketched side-by-side, and often tackled similar themes and locations in their paintings. This close collaboration is a distinctive feature of their careers.

While their styles were closely related, subtle differences might be discerned by specialists. However, they shared a common approach characterized by bright palettes, atmospheric sensitivity, and a focus on landscape and genre scenes within the Orientalist tradition. They both exhibited their works regularly, often at the same venues, reinforcing their public image as a fraternal artistic partnership.

This shared focus and travel likely created a supportive and stimulating environment for both brothers. They could exchange ideas, critique each other's work, and share the challenges and discoveries of painting en plein air in unfamiliar environments. Their joint exploration of Algeria and Tunisia resulted in a substantial body of work that collectively offers a rich visual record of the region as seen through their particular artistic lens. The exact nature of their day-to-day collaboration – whether they ever worked on the same canvas, for instance – is not always clear, but their shared exhibitions and thematic concerns underscore their intertwined artistic paths.

Exhibitions, Societies, and Recognition

Alexis Auguste Delahogue was an active participant in the Parisian art world. He regularly submitted his paintings to the prestigious Salon des Artistes Français, one of the primary venues for artists seeking official recognition and patronage during that era. Exhibiting at the Salon was crucial for building a reputation and attracting buyers. Delahogue's consistent presence there indicates a degree of success and acceptance within the mainstream art establishment.

Furthermore, he was deeply involved in organizations dedicated to promoting Orientalist art. He was a member of the Société des Artistes Algériens et Orientalistes (Society of Algerian and Orientalist Artists), founded in 1889, and the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Society of French Orientalist Painters), established in Paris in 1893 under the impetus of artists like Léonce Bénédite, who later became the director of the Musée du Luxembourg. These societies organized dedicated exhibitions, fostering a sense of community among artists working with North African and Middle Eastern themes and promoting their work to the public and collectors.

Membership in these societies placed Delahogue firmly within the network of prominent Orientalist painters of his time. His colleagues and fellow exhibitors likely included artists such as Étienne Dinet (who eventually converted to Islam and lived in Algeria), Gustave Guillaumet (renowned for his realistic depictions of Algerian life), the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, a leading figure of the older generation known for his highly detailed, academic Orientalist scenes. Delahogue's work found favor with collectors, and his paintings achieved respectable prices at auction during his lifetime and continue to be sought after today, attesting to their enduring appeal.

Contextualizing Delahogue: French Orientalism

To fully appreciate Alexis Auguste Delahogue's contribution, it's essential to place him within the broader context of French Orientalism. This artistic and cultural movement, which flourished throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th, was complex and multifaceted. It began arguably with Napoleon's Egyptian campaign and gained significant momentum with the Romantic generation, particularly Eugène Delacroix, whose 1832 trip to Morocco and Algeria profoundly influenced his art and inspired countless others.

Delacroix's vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and romanticized depictions of North African life set a precedent. Later artists approached the "Orient" in diverse ways. Some, like Jean-Léon Gérôme, favored meticulous detail and dramatic, often historically or ethnographically themed scenes. Others, like Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps or Théodore Frère, focused on landscapes and genre scenes. Artists like Gustave Guillaumet brought a greater sense of realism and empathy to their depictions of the hardships and daily life of the Algerian people.

By the time Delahogue began his career, Orientalism was well-established but also evolving. The influence of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism led some artists, including Delahogue, to prioritize light, color, and atmosphere over narrative or ethnographic precision. His work can be seen as part of this later phase, where the visual sensations offered by the North African environment became a primary subject. He shared this interest in light and landscape with contemporaries like Étienne Dinet, although Dinet's deep personal connection and eventual conversion gave his work a unique perspective.

It is also important to acknowledge the critical perspectives on Orientalism, most famously articulated by Edward Said. Critics argue that Orientalist art often presented stereotyped, romanticized, or patronizing views of non-European cultures, reinforcing colonial power structures and the idea of Western superiority. While Delahogue's work primarily focuses on landscape and atmosphere, it still participates in this broader tradition of European artists interpreting and representing the "Other." His paintings, like those of his contemporaries, reflect the interests, assumptions, and artistic conventions of their time and place.

Influence and Legacy

Alexis Auguste Delahogue's legacy lies primarily in his contribution to the Orientalist genre, specifically his evocative renderings of North African light and landscape. Alongside his brother Eugène, he produced a consistent and high-quality body of work that captured the imagination of the French public and contributed to the visual culture surrounding the colonies. His paintings offered viewers in Europe a glimpse into distant lands, filtered through an appealing aesthetic that blended realistic observation with the heightened color and light associated with modern French painting.

His work is valued today for its artistic merit – the skillful handling of color, the effective compositions, and the palpable sense of atmosphere. His paintings serve as historical documents, reflecting not only the landscapes and life of North Africa at the turn of the century but also the European fascination with the region. While perhaps not as revolutionary as the leading figures of Impressionism or Post-Impressionism like Monet, Degas, or Gauguin, Delahogue carved out a significant niche within the popular and critically recognized field of Orientalist painting.

His influence can be seen in the continuation of landscape painting traditions that emphasize light and atmosphere. His works are held in various museum collections, particularly in France, and frequently appear at auction, where they command interest from collectors of Orientalist art. He represents a generation of skilled French painters who synthesized academic training with modern sensibilities, applying them to the popular themes of their day. His dedication to capturing the unique visual character of North Africa ensures his place in the history of French Orientalist art.

Conclusion: A Painter of Sun and Sand

Alexis Auguste Delahogue was a dedicated and talented painter whose artistic identity was forged in the sunlight of North Africa. Together with his twin brother Eugène, he explored the landscapes, cities, and deserts of Algeria and Tunisia, translating his experiences into luminous and atmospheric canvases. As an active member of the French Orientalist movement, he exhibited regularly, gained recognition, and contributed significantly to the genre through his distinctive focus on light, color, and the evocative power of landscape. While situated within the complex historical context of Orientalism, his work endures for its aesthetic qualities and its ability to transport the viewer to the sun-drenched environments he knew so well. His paintings remain a testament to a lifelong engagement with the visual splendors of the Maghreb, captured with skill and sensitivity.