Eugène-François Adolphe Deshayes (1828–1891) stands as a notable figure in nineteenth-century French art, particularly recognized for his contributions to Orientalist painting and landscape depiction. Although born in Algiers, the capital of French Algeria, Deshayes was unequivocally a French artist, carrying his national identity throughout his life and career. His work often reflects a deep connection to the Mediterranean world, especially North Africa, rendered through a lens influenced by both academic tradition and a personal sensitivity to light and place. His artistic journey took him from North Africa to the heart of the Parisian art world, where he achieved considerable recognition.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Algiers and Paris

Born in Algiers in 1828 to a French father, Eugène Deshayes developed a passion for drawing and painting at a young age. His early life was marked by challenging family circumstances, but his artistic inclinations found support, notably from his elder brother who financed his initial studies. Deshayes enrolled in the National School of Fine Arts (École des Beaux-Arts) in Algiers, laying the foundational skills for his future career. While some accounts suggest a less than diligent approach to formal studies initially, his innate talent was evident.

During his formative years in Algiers, Deshayes began forging connections within the local artistic milieu. He befriended Charles Jourdan, noted not as the later shoe designer, but described in sources as an enlightened art enthusiast and potentially a landscape painter associated with the Barbizon spirit, who owned a property where Deshayes painted. He may also have encountered figures like the landscape painter Charles Labbé, further immersing himself in the artistic currents of the colony.

Seeking to advance his training, Deshayes eventually made his way to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world. There, he continued his education, studying under masters such as Léon Joubert and potentially Benoît. Perhaps more significantly, he is mentioned as having spent time in the circle, possibly even the studio, of the towering figure of academic and Orientalist painting, Jean-Léon Gérôme. Some sources even suggest Deshayes served as a model in Gérôme's studio, receiving particular attention from the master, an experience that would undoubtedly have been deeply influential.

Navigating the Parisian Art World: The Salon

The Paris Salon was the paramount institution for an artist seeking recognition in nineteenth-century France. Organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, it was the official, juried exhibition that could make or break careers. For Deshayes, participation in the Salon became a regular feature of his professional life. He exhibited his works there on numerous occasions, gaining visibility and critical attention.

His submissions likely included the subjects he became known for: evocative scenes of the Mediterranean coast, marine paintings capturing the interplay of sea and light, and, increasingly, depictions of North Africa. Success at the Salon meant not only prestige but also potential state purchases, commissions, and the attraction of private patrons. Deshayes's ability to consistently show his work indicates a level of acceptance and respect within the competitive Parisian art establishment. His paintings resonated with the public and critics, contributing to his growing reputation.

The Salon system, while sometimes criticized for its conservatism, was the primary stage for artists like Deshayes who worked within established genres like landscape and historical or genre painting, albeit infused with the popular themes of Orientalism. His participation cemented his status as a professional artist contributing to the diverse tapestry of French art during the Second Empire and early Third Republic.

The Allure of the Orient: Deshayes and Algeria

Deshayes's connection to North Africa was profound and deeply personal, setting him apart from many of his contemporaries who visited the "Orient" as travelers. Having been born in Algiers, the sights, sounds, and light of Algeria were part of his formative experience. This intrinsic familiarity likely informed the authenticity and sensitivity found in his depictions of the region. His work aligns with the broader nineteenth-century European fascination with North Africa and the Middle East, a movement known as Orientalism.

Orientalism in art, famously explored by painters like Eugène Delacroix with his vibrant depictions of Morocco, and Jean-Léon Gérôme with his meticulously detailed scenes of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, often blended ethnographic observation with romanticized or dramatic interpretations. Other key figures included Théodore Chassériau, whose work often possessed a unique blend of classicism and romantic exoticism. Deshayes contributed to this genre, focusing primarily on the landscapes and daily life of Algeria.

His paintings often capture the unique quality of North African light – the harsh brightness of midday or the warm glow of sunrise and sunset over the desert or coastal plains. He depicted scenes such as encampments near oases, bustling marketplaces, quiet courtyards, and the distinctive architecture of Algerian towns and countryside. Works like Campement devant l'Oasis de Bou-Saâda (Camp before the Oasis of Bou-Saâda) exemplify this focus, presenting a vision of life on the edge of the Sahara.

Unlike some Orientalists who focused on harem scenes or dramatic historical events, Deshayes often seemed more interested in the landscape itself and the integration of human activity within it. His Algerian scenes convey a sense of place, atmosphere, and the textures of the environment, reflecting his firsthand knowledge and deep affection for his native land.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Eugène Deshayes's artistic style is characterized by a blend of academic training and a personal response to his subject matter, particularly landscape and light. Sources suggest he looked towards the grand traditions of seventeenth-century history painting for inspiration, citing masters like Eustache Le Sueur and Charles Le Brun, known for their complex compositions and narrative clarity within the French classical tradition. The influence of Baroque masters like Peter Paul Rubens and the Carracci family (Annibale, Agostino, Ludovico), celebrated for their dynamic compositions, rich color, and dramatic intensity, is also noted.

This grounding in historical painting likely informed Deshayes's approach to composition, lending structure and sometimes a subtle dramatic flair to his works, even when depicting landscapes or genre scenes. However, his style was adapted to his chosen subjects. In his Mediterranean and Algerian landscapes, the emphasis often falls on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere. His brushwork could range from detailed rendering, particularly in architectural elements or figures, to broader, more suggestive strokes in skies or distant terrain.

His color palette was likely adapted to the intense light of North Africa, employing warm earth tones, vibrant blues, and strong contrasts to convey the sun-drenched environment. His understanding of light and shadow was crucial in creating depth and volume, whether depicting the intricate play of light in a garden or the stark shadows cast in a desert landscape.

While associated with Orientalism, his work might be seen as less overtly romanticized or dramatic than Delacroix's, and perhaps less photographically precise than Gérôme's. He carved his own niche, focusing on the lyrical beauty and specific character of the Algerian landscape and its inhabitants, filtered through a French academic sensibility. His friendship with Charles Jourdan, potentially a Barbizon-influenced painter, might also suggest an appreciation for direct observation from nature, a hallmark of the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot or Théodore Rousseau.

Representative Works and Recurring Themes

Several specific works help illustrate the scope and focus of Eugène Deshayes's art:

Campement devant l'Oasis de Bou-Saâda (Camp before the Oasis of Bou-Saâda): This oil painting likely depicts a scene common in Orientalist art – a nomadic or semi-nomadic encampment near a vital water source. It would showcase Deshayes's ability to render the desert landscape, the specific architecture or vegetation of an oasis, and figures representing local life, all under the characteristic North African light.

Le cortège de la mariée (The Wedding Procession): This title suggests a genre scene, focusing on local customs and traditions. Such paintings were popular with European audiences curious about exotic cultures. It would offer Deshayes an opportunity to depict colorful costumes, group dynamics, and perhaps specific architectural settings, blending ethnographic interest with artistic composition.

Vallon de la petite Kabylie au soleil couchant (Valley of Little Kabylia at Sunset): This landscape painting focuses on a specific region of Algeria known for its distinct geography and culture. The emphasis on sunset indicates a study in light and color, capturing the fleeting moments of dusk transforming the landscape. It highlights his dedication to capturing specific locations and atmospheric effects.

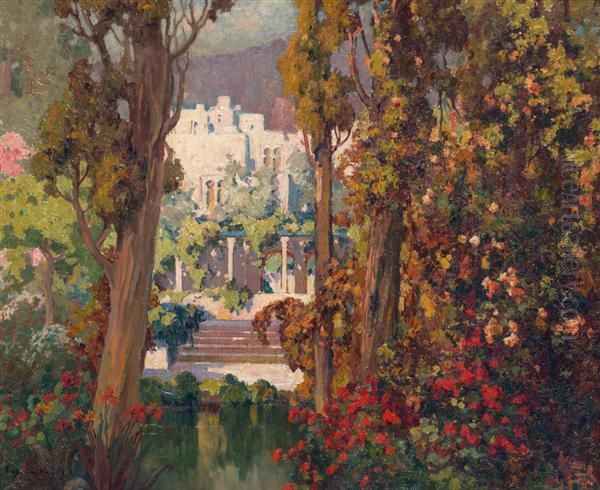

Villa et Jardin d'Algérie (Villa and Garden of Algeria) and Le Jardin d'Alger (The Garden of Algiers): These titles point to an interest in cultivated spaces within the Algerian setting. Gardens and villas offered subjects rich in architectural detail, lush vegetation contrasting with the arid surroundings, and the interplay of light and shadow through foliage and structures. These works might reflect the European colonial presence or simply capture the beauty of these man-made oases. One work is noted for using oil and relief techniques, suggesting some experimentation.

Vue de la ville et de la cathédrale de Rouen (View of the City and Cathedral of Rouen): This work, described as a sketch using graphite, ink, watercolor, and gouache, shows that Deshayes did not limit himself exclusively to North African subjects. It demonstrates his skill in architectural rendering and his work in different media, capturing a scene from his native France.

Port de pêcheurs (Fishermen's Port): This title indicates his interest in marine subjects, likely depicting a Mediterranean fishing harbor, possibly in France or North Africa. Such scenes allowed for the study of boats, water, reflections, and the daily activities of coastal communities.

These examples illustrate recurring themes in Deshayes's oeuvre: the landscapes of Algeria (desert, oasis, Kabylia), scenes of local life and customs, architectural studies (villas, gardens, cathedrals), and marine views. Central to many of these was his fascination with the effects of natural light.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

Eugène Deshayes continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, building a solid reputation based on his skillful execution and appealing subject matter. His work was appreciated both in France and potentially internationally, finding its way into collections and achieving recognition through the Salon system. Some sources mention honors bestowed upon him, such as the French Legion of Honour (possibly related to naval art, given his marine interests) and a Royal Art Medal, although specifics require further verification.

He passed away in 1891 (some sources state 1890), leaving behind a body of work that contributes significantly to the Orientalist and landscape traditions in French art. His unique perspective as an Algiers-born Frenchman gave his depictions of North Africa a particular resonance.

It is important to distinguish Eugène-François Adolphe Deshayes (1828-1891) from other notable individuals with similar names. This includes the prominent French geologist and paleontologist Gérard Paul Deshayes (1795–1875). Furthermore, historical records and art market data sometimes mention another French painter named Eugène Deshayes, reportedly born later (perhaps around 1862 or 1865) and also associated with Algerian subjects, sometimes undertaking official missions. The biographical details, particularly regarding later expeditions (like one mentioned for 1902), seem to occasionally conflate these two artists. The focus here remains firmly on the earlier figure, Eugène-François Adolphe Deshayes (1828-1891).

Interestingly, the artistic lineage continued in the family. A son, also named Eugène Deshayes, reportedly became involved in the printing trade, specifically lithography, working with major twentieth-century artists like Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger. This connection highlights the family's enduring engagement with the art world across generations, transitioning from traditional painting to the collaborative field of printmaking that served the avant-garde.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Light and Place

Eugène-François Adolphe Deshayes remains a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century French art. His dual heritage – French nationality and Algerian birth – provided a unique foundation for his artistic explorations, particularly within the popular Orientalist movement. He moved beyond simple exoticism to convey a genuine sense of place in his depictions of North Africa, demonstrating a masterful handling of light and atmosphere.

Influenced by academic traditions and historical masters like Le Sueur, Le Brun, and potentially Gérôme, yet responsive to the natural world and the specific character of the Mediterranean and Algeria, Deshayes created a body of work appreciated for its skill, sensitivity, and evocative power. His landscapes, marine paintings, and genre scenes, exhibited regularly at the Paris Salon, secured his reputation during his lifetime. Today, his paintings offer valuable insights into the artistic currents of his time and provide enduring visions of the lands he knew so well, captured with the brush of a dedicated and talented French painter.