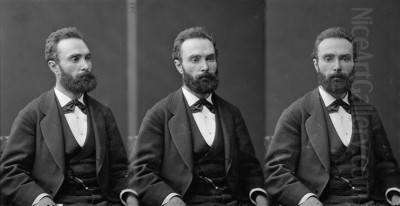

Gustave Achille Guillaumet stands as a significant yet perhaps less universally recognized figure within the vibrant tapestry of 19th-century French art. Primarily celebrated as an Orientalist painter, his work diverged from many contemporaries through its profound empathy and commitment to realism, particularly in his depictions of Algeria. Forsaking overt exoticism for nuanced observation, Guillaumet dedicated much of his relatively short career to capturing the unique light, landscapes, and human experiences of North Africa, leaving behind a legacy that continues to resonate for its artistic merit and historical insight.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on March 26, 1840, in Puteaux, then a suburb west of Paris, Gustave Guillaumet entered a world undergoing significant social and artistic transformation. His family background provided a degree of financial stability, a factor that would later grant him considerable artistic independence, freeing him from the constant pressure to produce commercially driven work that constrained many artists of his era. This economic freedom allowed him to pursue subjects and approaches aligned with his personal vision.

His formal artistic education was thorough and grounded in the academic traditions of the time. Guillaumet initially studied under François-Édouard Picot, a respected painter known for his historical and portrait subjects, firmly rooted in the Neoclassical lineage of Jacques-Louis David. This training would have instilled a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and anatomical accuracy.

He further honed his skills under Félix-Joseph Barrias, another academic painter whose oeuvre included historical scenes but also touched upon Orientalist themes. Barrias himself was a successful artist, exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon. Studying with these masters provided Guillaumet with the technical proficiency expected for a career painter aiming for recognition within the established art institutions.

Guillaumet's education culminated at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training in France. Here, he would have been immersed in a curriculum emphasizing classical ideals, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters. The prevailing artistic climate was still heavily influenced by figures like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose emphasis on line and classical form set a high standard, even as new movements began to challenge academic conventions.

The Call of the Orient: First Encounters with Algeria

A pivotal moment in Guillaumet's burgeoning career arrived in 1861 when he won the prestigious Second Grand Prix de Rome. While not the coveted first prize, this award carried significant honor and, crucially, provided funding for travel. Traditionally, Prix de Rome winners journeyed to Italy to study classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces. However, Guillaumet's path took a different, life-altering direction.

In 1862, instead of heading south to Rome, Guillaumet embarked on his first voyage to Algeria. This French colony, conquered starting in 1830, held a powerful allure for many European artists and writers, often viewed through a lens of romanticism and exoticism. Artists like Eugène Delacroix had already journeyed to North Africa decades earlier, bringing back vibrant sketches and paintings that fueled the European imagination.

Guillaumet's initial experience, however, was far from romantic. Shortly after arrival, he contracted a severe case of malaria, a debilitating illness that forced him into a lengthy convalescence. He spent three months recovering in a military hospital, an experience that offered an unvarnished, close-up view of colonial life and the harsh realities faced by both Europeans and Algerians. This difficult beginning, rather than deterring him, seemed to forge a deep and lasting connection to the land and its people.

An Enduring Fascination: Return Trips and Deepening Understanding

The 1862 trip marked not an isolated adventure but the beginning of a lifelong engagement with Algeria. Over the subsequent years, Guillaumet would return to North Africa numerous times – sources suggest as many as nine distinct journeys. This repeated immersion distinguishes him from artists who made brief tours or relied heavily on photographs and artifacts back in their Paris studios, such as the highly successful Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Guillaumet sought a deeper understanding, venturing beyond the coastal cities into the more remote and challenging interior. He spent considerable time exploring regions like the Kabylie mountains, the Hodna basin, and the areas around the oasis town of Bou Saada, often considered a gateway to the Sahara. He lived among the local populations, observing their daily routines, social customs, and struggles against a demanding environment.

His commitment mirrored that of Eugène Fromentin, another French artist who was both a painter and a respected writer, known for his insightful books Un Été dans le Sahara (A Summer in the Sahara) and Une Année dans le Sahel (A Year in the Sahel). Like Fromentin, Guillaumet aimed for an authenticity born from direct, prolonged experience, striving to portray the people and landscapes with dignity and accuracy.

Artistic Style: Naturalism, Light, and Atmosphere

Guillaumet's artistic style is best characterized as a form of Naturalism, closely aligned with Realism but often imbued with a subtle poetic sensibility. He largely eschewed the highly dramatic or overtly sensualized scenes favored by some Orientalists. Instead, he focused on the truthful depiction of what he observed, paying meticulous attention to detail, texture, and, above all, the effects of light.

The intense, unique light of North Africa became a central element in his work. He masterfully captured the blinding glare of the midday sun, the soft, warm hues of dawn and dusk, and the cool, ethereal light of the moonlit desert. His paintings often explore the interplay of light and shadow, using it to define form, create mood, and emphasize the vastness or intimacy of a scene. His fascination was so profound that he even authored an essay on the subject, articulating his observations on how light shaped perception and environment in Algeria.

While trained in the academic tradition, Guillaumet's handling of paint and his sensitivity to atmospheric effects show an awareness of contemporary trends. His connection, through fellow artists like Achille Oudinot (a student of Camille Corot), to figures associated with the Barbizon School and early Impressionism, such as Corot himself, Charles-François Daubigny, and perhaps even Édouard Manet and Camille Pissarro, likely informed his approach to landscape and light, even if he never adopted Impressionist techniques wholesale. His focus remained on careful observation and rendering, but with a heightened sensitivity to transient effects.

Themes and Subjects: Capturing Algerian Life

Guillaumet's oeuvre provides a rich panorama of Algerian life and landscapes during the early decades of French colonial rule. His subjects were diverse, reflecting his wide-ranging observations. He painted sweeping desert vistas, emphasizing the stark beauty and imposing scale of the Sahara, often populated by solitary figures or camel caravans that underscore human fragility against nature's power.

He depicted the specific geography of regions he knew well, capturing the rugged terrain of the mountains and the vital importance of oases. Animals, particularly camels and horses – essential to desert life – feature prominently, rendered with anatomical accuracy and a sense of their integral role in the local economy and culture.

Crucially, Guillaumet dedicated significant attention to the people of Algeria. He painted scenes of daily life in villages and nomadic encampments (douars). Marketplaces, moments of rest, and communal activities appear in his work. He showed a particular interest in the lives of women, depicting them engaged in traditional tasks like weaving, spinning wool, or fetching water from wells, often with a quiet dignity. Unlike some contemporaries who focused on imagined harem scenes, Guillaumet portrayed women within the context of their actual labor and social spaces.

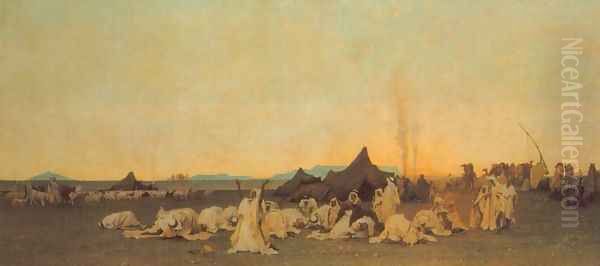

He did not shy away from depicting hardship. Several of his works address the themes of poverty, drought, and famine, reflecting the precariousness of life in an often unforgiving environment. These paintings stand as powerful social commentaries, imbued with a palpable sense of empathy for the suffering he witnessed. His depictions of prayer, such as the famous Evening Prayer in the Sahara, convey a sense of spiritual resilience amidst austerity.

Key Masterpieces: Defining Works

Several paintings stand out as defining examples of Guillaumet's artistic vision and skill:

Evening Prayer in the Sahara (c. 1863): Perhaps his most iconic work, this painting captures a group of men performing their sunset prayers in the vast emptiness of the desert. The warm, fading light, the long shadows, and the simple devotion of the figures create a powerful atmosphere of spirituality and tranquility. It exemplifies his mastery of light and his respectful portrayal of local customs.

Laghouat, Algerian Sahara (various versions, e.g., 1879): Guillaumet painted the oasis town of Laghouat multiple times. These works often depict the town nestled amidst palm groves, contrasting the built environment with the surrounding desert. They capture the unique atmosphere of these vital desert settlements, showcasing his ability to render architecture and vegetation under the specific Algerian light.

Douar Women at the River (or similar titles, e.g., Weavers at Bou-Saada): These paintings focus on the communal work of women, often depicting them washing clothes or, more frequently, engaged in textile production. Works like The Weavers of Bou-Saada highlight the intricate processes of spinning and weaving, central to the local economy and culture. Guillaumet observed these activities closely, rendering the figures and their tools with detailed realism. He sometimes created multiple versions or studies, indicating the importance of these themes to him.

Famine in Algeria (c. 1869): This stark and moving painting addresses the devastating consequences of drought and famine. It depicts emaciated figures huddled together, conveying profound suffering and despair. This work marks a departure from more picturesque scenes and demonstrates Guillaumet's willingness to confront the harsh realities of Algerian life, reflecting a deep humanism.

La Halte (The Halt or The Stopover, exhibited 1863): An early success, this work likely depicted a nomadic group resting during their travels, showcasing scenes from the Kabylie region or other areas visited on his initial trips. It established his reputation for capturing the authentic details of nomadic life and landscape.

Caravan in the Desert (c. 1877-78): This painting captures the epic scale of desert travel, depicting a long caravan traversing the reddish sands near the entrance to the Sahara. It reportedly includes a portrait of the explorer Paul Flatters, adding a specific historical dimension. The work emphasizes the vastness of the landscape and the arduous nature of desert journeys.

Other notable works include landscapes like View Near Barbonza and Trees of a Rocky Hillside, demonstrating his skill in pure landscape painting, and smaller, intimate studies like Fontarabi, capturing specific locations or moments with sensitivity.

Guillaumet and His Contemporaries: Influences and Connections

Guillaumet operated within a complex artistic landscape. As an Orientalist, he was part of a broad movement that included pioneers like Delacroix and Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, established figures like Théodore Chassériau, and contemporaries like Gérôme and Fromentin. While sharing the thematic focus on North Africa and the Middle East, Guillaumet's approach differed. He generally avoided the ethnographic precision bordering on the clinical seen in Gérôme, and the high romantic drama of Delacroix, carving out a niche characterized by naturalistic observation and empathetic portrayal.

His academic training under Picot and Barrias grounded him in traditional techniques, and he was reportedly considered by some to have surpassed his master Barrias in talent and originality. His success at the Paris Salon, the main venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage, indicates his acceptance within the official art world, even as his subject matter pushed beyond conventional European themes.

His connections to the circle around Corot and the Barbizon painters, facilitated by artists like Oudinot, suggest an openness to newer approaches to landscape painting, particularly concerning light and atmosphere. While not an Impressionist, his work shares the Impressionists' interest in capturing the effects of natural light through direct observation, a contrast to the studio-bound methods of many academic painters. He also participated in collaborative projects, such as one initiated by Camille Cabillot-Lassalle involving small paintings by various artists, showing his engagement with the broader artistic community.

Beyond the Canvas: Tableaux algériens

Guillaumet's engagement with Algeria extended beyond painting. He authored a collection of writings published posthumously in 1888 as Tableaux algériens (Algerian Scenes). This book comprises essays, sketches, and reflections based on his extensive experiences in the country. It offers invaluable insights into his perspective, revealing a deep curiosity about and respect for Algerian culture, customs, and the challenges faced by its people.

The text complements his visual art, providing verbal descriptions that echo the sensitivity and observational detail found in his paintings. Through dialogues, narratives, and descriptive passages, Tableaux algériens reveals Guillaumet's nuanced understanding of the complex social dynamics of colonial Algeria and his genuine connection to the individuals he encountered. It stands as a significant literary contribution alongside his artistic output, further distinguishing him from artists whose engagement with the Orient remained primarily visual or superficial.

Reception and Recognition

During his lifetime, Guillaumet achieved considerable recognition. His regular participation in the Paris Salon brought his work to public and critical attention. He received medals and honors, and his paintings were acquired by the French state and private collectors, indicating significant contemporary success. His financial independence allowed him to travel extensively and paint according to his own inclinations, contributing to the consistency and personal nature of his vision.

Critics generally praised his technical skill, his mastery of light, and the perceived authenticity of his depictions. He was often lauded for offering a more truthful and less sensationalized view of Algeria compared to some of his peers. His empathetic approach was noted, setting him apart from more detached or purely ethnographic portrayals.

Later Years and Tragic Undertones

In his later works, some observers note a shift towards more somber or tragic themes, perhaps reflecting a deepening awareness of the hardships inherent in the lives he depicted, or possibly personal introspection. Paintings addressing famine or depicting solitary, contemplative figures suggest this evolving perspective.

Tragically, Gustave Guillaumet's promising career was cut short. He died suddenly in Paris on March 14, 1887, from peritonitis, just shy of his 47th birthday. His relatively early death meant that his full potential may not have been realized, leaving a void in the French art scene and silencing a unique voice in Orientalist painting.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite his premature death, Gustave Guillaumet left an indelible mark on 19th-century art. He is considered one of the most important and sensitive French Orientalist painters, valued for his commitment to realism, his extraordinary handling of light, and his humanistic approach to his subjects. His work offers a valuable visual record of Algeria during a specific historical period, documenting landscapes, ways of life, and the encounter between European and North African cultures under colonialism.

His influence on subsequent artists is perhaps subtle but significant. His authentic portrayal of North African light and life provided a touchstone for later generations of artists who traveled to the region, including figures associated with Fauvism like Henri Matisse and André Derain, who sought inspiration in the vibrant colors and forms of the Maghreb early in the 20th century.

Today, Guillaumet's paintings are held in major museum collections across the world, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Louvre in Paris, as well as institutions in Algeria and the United States. Renewed scholarly and public interest is evidenced by exhibitions, such as a major retrospective held in Paris, La Rochelle, and Roubaix in 2018-2019, titled "Guillaumet, The Algerian Light," which reaffirmed his importance and brought his luminous depictions of Algeria to a new audience.

Conclusion

Gustave Achille Guillaumet occupies a unique position in art history. He was an artist deeply shaped by his academic training yet driven by a personal quest for authenticity derived from direct experience. His numerous journeys to Algeria resulted in a body of work that captures the land and its people with remarkable sensitivity and a masterful command of light. Moving beyond the prevalent exoticism of much Orientalist art, Guillaumet offered a nuanced, empathetic, and profoundly human vision of North Africa. His paintings remain compelling not only for their aesthetic beauty but also for their enduring power as documents of a specific time and place, seen through the eyes of a deeply observant and compassionate artist.