Henry Roderick Newman stands as a unique figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. An expatriate who spent the majority of his prolific career in Florence, Italy, Newman distinguished himself through his exquisite watercolor paintings, characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant color, and a profound reverence for nature and architectural beauty. Deeply influenced by the writings of the English art critic John Ruskin and the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Newman carved a niche for himself, creating a body of work that continues to fascinate art historians and enthusiasts alike for its technical brilliance and earnest devotion to its subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in New York around 1843, Henry Roderick Newman's early life, though not extensively documented, set the stage for an artistic journey that would take him far from his native land. His initial artistic inclinations likely developed in an America where the Hudson River School, with painters like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, celebrated the grandeur of the natural landscape with detailed realism. This prevailing atmosphere of appreciating nature's intricacies would resonate with Newman's later artistic philosophy.

His formal artistic training is believed to have commenced in the late 1850s. Some accounts suggest he studied for a brief period with Thomas Charles Farrer, an English-born artist who was a key proponent of Pre-Raphaelite principles in America. Farrer, along with other artists like John William Hill and Charles Herbert Moore, formed part of a small but dedicated group of American Pre-Raphaelites who championed Ruskinian ideals of "truth to nature." This early exposure to Pre-Raphaelite thought, emphasizing close observation and detailed rendering, would prove formative for Newman.

By 1861, Newman was beginning to establish himself, exhibiting his work at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York. His early works, though fewer survive or are well-documented, likely showed the nascent signs of the meticulous style that would become his hallmark. The artistic environment in America at this time was diverse, with figures like Winslow Homer beginning to make their mark, and the influence of European art, particularly from Düsseldorf and Paris, growing. However, Newman's path would be distinctly shaped by English, rather than continental European, aesthetic theories.

The Call of Europe and the Florentine Haven

A pivotal moment in Newman's life and career occurred around 1870 when, possibly due to health reasons (he reportedly suffered from lung issues), he made the decision to leave America and travel to Europe. This was not an uncommon path for American artists of the period, many of whom, like James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent, sought training, inspiration, and a more established art market abroad. Newman initially traveled in France, but it was Italy, and specifically Florence, that captured his heart and became his permanent home.

Florence, with its rich artistic heritage, stunning Renaissance architecture, and vibrant expatriate community, provided an ideal environment for Newman. He settled there and quickly became absorbed in depicting its iconic landmarks, ancient churches, and the subtle beauty of its surrounding Tuscan landscapes. The city offered an inexhaustible supply of subjects that aligned perfectly with his developing artistic sensibilities. It was in Florence that his commitment to the Pre-Raphaelite ethos, particularly as filtered through the writings of John Ruskin, would fully blossom.

The decision to primarily work in watercolor, a medium often considered secondary to oil painting at the time, was also significant. Newman, however, elevated watercolor to a level of precision and luminosity that rivaled oil, demonstrating its capacity for capturing the most intricate details and subtle atmospheric effects. This mastery would become one of his most recognized achievements.

The Enduring Influence of John Ruskin

No discussion of Henry Roderick Newman's art is complete without acknowledging the profound and lasting impact of John Ruskin. Ruskin, the preeminent English art critic of the Victorian era, was a fervent advocate for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt – who sought to reject the formulaic academic art of the time and return to the detailed realism and vibrant color of Quattrocento Italian art. Ruskin's writings, particularly "Modern Painters," championed the principle of "truth to nature," urging artists to observe and record the natural world with scientific accuracy and heartfelt reverence.

Newman became a devoted disciple of Ruskin's teachings. He not only absorbed Ruskin's aesthetic philosophy but also came to know the critic personally. Ruskin, in turn, became a significant patron and admirer of Newman's work, recognizing in the American artist a genuine commitment to the ideals he espoused. This was a rare endorsement, as Ruskin was often critical of American artists and the burgeoning American culture.

Ruskin particularly admired Newman's architectural studies and his delicate floral still lifes. He commissioned several works from Newman and praised his ability to capture the essence of his subjects with both precision and poetic sensibility. For Newman, Ruskin's approval was not just a professional boon but a validation of his artistic direction. He diligently applied Ruskinian principles, spending countless hours, sometimes months or even years, on a single watercolor, building up layers of transparent washes to achieve the desired depth, detail, and luminosity. This meticulous approach, directly inspired by Ruskin, set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Travels and Inspirations: Italy, Egypt, and Japan

While Florence remained his base, Newman's artistic curiosity and Ruskin's encouragement led him to travel to other inspiring locales. His journeys provided him with fresh subjects and further opportunities to apply his detailed observational skills.

Italy, of course, was a constant source of inspiration. Beyond Florence, he painted in Venice, capturing the city's unique blend of architectural grandeur and watery reflections. His Venetian scenes, like his Florentine ones, are characterized by their careful delineation of architectural detail and their sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He sought out not just the famous vistas but also quieter corners and less-celebrated architectural elements, always with an eye for their intrinsic beauty and historical resonance.

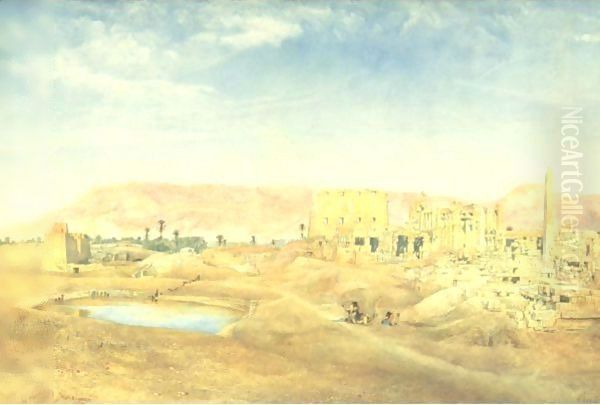

A significant chapter in Newman's artistic travels was his time spent in Egypt, beginning in the late 1870s and continuing with several subsequent visits. Following in the footsteps of other Western artists fascinated by the Orient, such as David Roberts and Jean-Léon Gérôme, Newman was drawn to the monumental ruins of ancient Egypt. He produced a remarkable series of watercolors depicting temples at Philae, Karnak, and Luxor. These works are notable for their archaeological accuracy, their rendering of the texture of ancient stone, and their depiction of the brilliant Egyptian light. Ruskin himself encouraged these Egyptian studies, seeing in them an opportunity to preserve a visual record of these magnificent, and often vulnerable, historical sites.

Later in his career, in the 1890s, Newman also traveled to Japan. This was a period when Japanese art and aesthetics, known as Japonisme, were having a profound impact on Western art, influencing Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh. Newman's Japanese works, primarily floral studies and depictions of temples, show his characteristic attention to detail, but also perhaps a subtle absorption of Japanese compositional principles and a focus on the delicate beauty of individual natural forms. His flower paintings from this period are particularly exquisite, showcasing his mastery in rendering the intricate structures and vibrant colors of blossoms.

Artistic Style and Meticulous Technique

Henry Roderick Newman's artistic style is unmistakably his own, yet firmly rooted in the Pre-Raphaelite tradition. His primary medium was watercolor, which he handled with extraordinary skill and patience. He typically worked on a moderately textured paper, often Whatman, and employed a technique of applying multiple layers of transparent washes to build up color and form. This allowed him to achieve a remarkable luminosity and depth, far removed from the broader, more suggestive watercolor styles of some of his contemporaries.

Detail was paramount. Whether depicting the intricate facade of a Florentine cathedral, the delicate petals of a rose, or the hieroglyphs on an Egyptian temple, Newman rendered his subjects with an almost microscopic precision. This was not mere photographic accuracy; it was an act of devotion, an attempt to capture the essential truth and beauty of the object as he perceived it. His lines were crisp and controlled, and his colors, while often vibrant, were carefully modulated to reflect natural appearances.

His compositions were generally straightforward and descriptive, focusing the viewer's attention on the subject itself. In his architectural pieces, he often chose perspectives that highlighted the structural beauty and historical character of the buildings. He was particularly adept at conveying the texture of stone, the play of light on surfaces, and the subtle weathering that spoke of age and endurance. His depictions of Florence's Duomo, for instance, are celebrated for their accuracy and their ability to evoke the spiritual and aesthetic power of the structure.

In his floral still lifes, Newman demonstrated a similar dedication to detail and a profound appreciation for the natural world. Each petal, leaf, and stem was rendered with loving care, capturing not just the form but also the delicate vitality of the plant. These works, often small in scale, are jewels of botanical art, reflecting the Victorian era's fascination with botany and the symbolic language of flowers. They also clearly show the influence of Ruskin's call to study nature closely, as well as the precedent set by earlier masters of botanical illustration.

Notable Works: A Legacy in Watercolor

Throughout his long career, Henry Roderick Newman produced a significant body of work, much of which is now held in major museum collections and private hands. Several key pieces and subject categories stand out as representative of his artistic achievements.

His depictions of Florentine architecture are perhaps his most iconic. Works such as The Cathedral at Florence (Duomo), Santa Maria Novella, Florence, and An Easter Vigil in a Greek Church, Florence showcase his mastery in rendering complex architectural forms, intricate decorative details, and the interplay of light and shadow. These watercolors are not just topographical records; they are imbued with a sense of reverence for the history and spiritual significance of these sacred spaces. He often spent extended periods working on these subjects, meticulously capturing every nuance.

His Venetian scenes, while perhaps less numerous than his Florentine works, are equally compelling. He captured the unique atmosphere of Venice, its canals, palaces, and churches, with the same precision and sensitivity to light that characterized his other architectural studies. These works often highlight the rich textures and colors of Venetian Gothic architecture.

Newman's Egyptian watercolors form another important part of his oeuvre. Paintings like Temple of Philae or views of Karnak are remarkable for their archaeological detail and their evocation of the grandeur of ancient Egyptian civilization. He often worked under challenging conditions to produce these pieces, battling the desert heat and dust to capture the scenes before him. These works were highly valued by Ruskin and other contemporaries for their documentary as well as their artistic merit.

Finally, his floral still lifes, such as A Study of an Anemone, Roses, or his later Japanese Flower Arrangement, are exquisite examples of his delicate touch and keen observational skills. These intimate studies reveal his deep love for the natural world and his ability to find profound beauty in its smallest creations. They are often characterized by their vibrant, yet naturalistic, color and their almost tangible rendering of texture. These works connect him to a long tradition of botanical art, but with a distinctly Pre-Raphaelite intensity of observation.

Connections and Contemporaries: An American Abroad

As an American expatriate artist living in Florence, Henry Roderick Newman was part of a vibrant international artistic community, yet he maintained a somewhat distinct path due to his strong adherence to Ruskinian Pre-Raphaelitism. His most significant artistic relationship was undoubtedly with John Ruskin, who acted as a mentor, patron, and intellectual guide.

Among his American contemporaries, he shared a philosophical kinship with other artists influenced by Ruskin, such as Charles Herbert Moore, who also spent time in Italy and focused on detailed architectural and landscape studies. William Trost Richards was another American painter whose meticulous landscapes and seascapes, particularly his watercolors, show a similar dedication to Pre-Raphaelite principles of truth to nature, though Richards worked primarily in America and England.

While in Florence, Newman would have been aware of other American artists working there, such as the Symbolist painter Elihu Vedder, whose style and thematic concerns were quite different from Newman's. The expatriate community also included figures like Frank Duveneck and his "Duveneck Boys," who represented a looser, more painterly style influenced by the Munich School. Newman's meticulous, detailed approach set him apart from these trends.

His relationship with other prominent American expatriates like James McNeill Whistler or John Singer Sargent is less clear in terms of direct artistic influence, as their styles diverged significantly from his. Whistler, with his emphasis on "art for art's sake" and tonal harmonies, represented an aesthetic almost antithetical to Newman's Ruskinian devotion to detailed representation. Sargent, while a master technician, moved towards a more bravura, impressionistic style. However, they were all part of the broader phenomenon of American artists seeking inspiration and careers in Europe.

Newman's dedication to Pre-Raphaelite ideals connected him more directly to the British art world and the legacy of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt. Though working a generation later and in a different medium, Newman can be seen as one of the most faithful American exponents of their core tenets, particularly the emphasis on detailed observation and brilliant color. He also admired the work of J.M.W. Turner, whose championing by Ruskin was a cornerstone of "Modern Painters," especially Turner's later, more detailed works.

Later Years, Legacy, and Artistic Achievements

Henry Roderick Newman continued to live and work in Florence until his death, which occurred around 1917 or 1918 (sources vary slightly). He remained dedicated to his meticulous watercolor technique and his chosen subjects throughout his career, largely unaffected by the sweeping changes in artistic styles that characterized the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the rise of Modernism.

His artistic achievements were recognized during his lifetime, primarily through the consistent exhibition of his works and the patronage of influential figures like John Ruskin and Charles Eliot Norton, a Harvard professor and friend of Ruskin. While he may not have received a plethora of formal awards in the modern sense, his success lay in his ability to sustain a career as a specialist in a demanding technique, creating works that were highly sought after by a discerning clientele. His watercolors were acquired by collectors in both Europe and America.

The legacy of Henry Roderick Newman is that of a dedicated and exceptionally skilled artist who remained true to his artistic convictions. For a period after his death, as artistic tastes shifted dramatically away from Victorian realism and Pre-Raphaelitism, his work, like that of many of his contemporaries, fell into relative obscurity. However, the latter half of the twentieth century and the early twenty-first century have seen a significant revival of interest in Victorian art and the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Critical Reception and Contemporary Re-evaluation

During his active years, Henry Roderick Newman's work was generally well-received by critics and collectors who appreciated his particular style. The endorsement of John Ruskin lent considerable weight to his reputation, especially among those who shared Ruskin's aesthetic values. His meticulous detail, luminous color, and the evident sincerity of his approach were frequently praised. His architectural renderings were valued for their accuracy and their ability to convey the spirit of place, while his floral studies were admired for their delicate beauty and botanical precision.

However, his unwavering commitment to a highly detailed, labor-intensive style meant that his output was not as voluminous as that of some other artists. Furthermore, as artistic trends moved towards greater abstraction, looser brushwork, and subjective expression, Newman's work might have appeared increasingly traditional or even anachronistic to some observers by the turn of the century.

In the contemporary art historical context, Newman is recognized as a significant, if somewhat specialized, figure. He is considered one of the foremost American artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and a master of the watercolor medium. His expatriate status places him within an important group of American artists who sought to engage with European artistic traditions while forging their own identities.

Modern scholarship has shed more light on his career, his relationship with Ruskin, and the specific contexts in which he worked, particularly in Florence and Egypt. Exhibitions featuring his work, or including him in broader surveys of American Pre-Raphaelitism or expatriate art, have helped to bring his exquisite watercolors to a wider audience. Museums with significant holdings of his work, such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Brooklyn Museum, and various university art galleries, play a crucial role in preserving and presenting his artistic heritage.

His art continues to appeal for its sheer technical brilliance, its earnest beauty, and its quiet intensity. In a world often characterized by rapid change and fleeting impressions, Newman's painstaking dedication to capturing the enduring qualities of architecture and nature offers a moment of focused contemplation and profound appreciation for the visible world. His unique position as an American artist who so thoroughly absorbed and practiced Ruskinian ideals abroad ensures his lasting place in the annals of art history. His works remain a testament to a singular artistic vision and an unwavering commitment to the pursuit of beauty through truth.