Anton Raphael Mengs stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of eighteenth-century European art. A German painter whose career unfolded across the major artistic centers of Dresden, Rome, and Madrid, Mengs was instrumental in steering artistic taste away from the exuberance of the late Baroque and Rococo towards the measured rationality and idealized forms of Neoclassicism. He was not merely a practitioner but also a theorist, a friend of the influential archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann, and a highly sought-after court painter. His life and work offer a fascinating insight into the intellectual and artistic currents of the Enlightenment era, bridging traditions and forging a path that many subsequent artists would follow.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

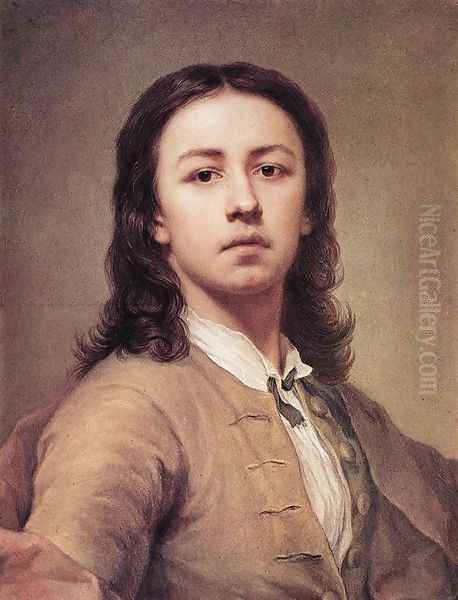

Anton Raphael Mengs was born on March 12, 1728, in Aussig, Bohemia (now Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic). His artistic destiny seemed preordained. His father, Ismael Mengs, was a respected Danish-born painter who served as a court painter in Dresden, Saxony. Ismael recognized his son's prodigious talent early on and subjected him to a rigorous, almost severe, artistic training regimen. The choice of his son's middle name, Raphael, was a clear indication of the high artistic lineage Ismael envisioned for him, referencing the High Renaissance master Raphael Sanzio.

In 1741, at the young age of thirteen, Mengs accompanied his father on a transformative journey to Rome. This was not a casual visit but a crucial part of his education. In the heart of the former Roman Empire and the cradle of the Renaissance, Mengs was immersed in the study of classical antiquity – its sculptures, architecture, and surviving paintings. He meticulously copied the works of Renaissance giants, particularly Raphael and Michelangelo, absorbing their principles of composition, form, and idealized human anatomy. This period laid the essential groundwork for his future artistic direction.

The Roman environment was intellectually stimulating. Mengs began to move in circles where the burgeoning ideas of Neoclassicism were being actively discussed. He learned from established artists and began to formulate his own artistic identity, one deeply rooted in the classical tradition but responsive to the intellectual climate of his time. His technical skill, honed under his father's demanding tutelage, quickly became apparent, particularly his mastery of drawing and pastel work.

Rome: The Crucible of Style and Belief

Mengs's initial years in Rome were formative not only artistically but also personally. He found the city's artistic heritage profoundly inspiring. The direct encounter with ancient Roman sculptures, the frescoes of Raphael in the Vatican Stanze, and the powerful figures of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel provided tangible models for the artistic ideals he was developing: clarity of form, compositional harmony, noble simplicity, and quiet grandeur.

During this period, Mengs also made a significant personal decision: he converted to Roman Catholicism. This conversion, while perhaps driven by genuine faith, also had practical implications for an artist seeking patronage in the papal city. Shortly thereafter, in 1748, he married Margarita Guazzi, a young Roman woman who had served as one of his models. While the marriage produced a large family (seven children survived him), contemporary accounts suggest it was not always a happy union, later strained by financial difficulties and perhaps personality clashes within the household.

Artistically, Mengs began to establish his reputation in Rome. He produced portraits and religious works that demonstrated his exceptional technical proficiency and his growing commitment to a style that synthesized elements from his revered masters – aiming for Raphael's expression, Correggio's grace, and Titian's color, all grounded in the study of classical form. He was beginning to distinguish himself from the prevailing late Baroque and Rococo styles, represented by artists still active in Rome.

The Influence of Winckelmann and Neoclassical Theory

A defining relationship in Mengs's life and career was his deep friendship with Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768). Winckelmann, a German archaeologist and art historian often considered the father of modern archaeology, arrived in Rome in 1755. The two men shared a profound admiration for classical antiquity, particularly Greek art, which Winckelmann championed as the pinnacle of aesthetic achievement. They became close intellectual companions, engaging in extensive discussions about art theory and history.

Winckelmann's seminal work, Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst (Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture, 1755) and his later Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (History of Ancient Art, 1764), provided the theoretical framework for Neoclassicism. He advocated for imitating the "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" of Greek art. Mengs became, in many ways, the visual interpreter of Winckelmann's ideas.

Mengs himself was not merely a painter but also a writer on art theory. In 1762, he published his own influential treatise, Gedanken über die Schönheit und über den Geschmack in der Malerey (Reflections on Beauty and Taste in Painting). In this work, he articulated his aesthetic philosophy, emphasizing the importance of selecting and combining the best elements from different masters (eclecticism) and from nature, guided by the ideal forms found in classical sculpture, particularly Greek examples. He stressed the primacy of drawing (disegno), clarity of composition, and the pursuit of an idealized beauty over mere imitation of reality. This text solidified his position as a leading proponent of Neoclassical theory. Their collaboration, with Winckelmann providing the historical and theoretical underpinning and Mengs translating these ideas into paint, was crucial for the movement's rise.

Court Painter in Dresden and Rome

Mengs's rising reputation did not go unnoticed by European courts. In 1745, while still relatively young, he was appointed court painter to Frederick Augustus II, the Elector of Saxony (who was also Augustus III, King of Poland), succeeding his father in Dresden. This prestigious appointment required him to divide his time between the Saxon capital and his beloved Rome.

His work for the Dresden court included portraits of the electoral family and religious paintings, such as the Ascension of Christ for the high altar of the Dresden Hofkirche (Court Church), completed around 1751 (though installed later). These works showcased his refined technique and his ability to work on a grand scale, blending his Neoclassical ideals with the requirements of courtly representation and religious devotion.

Even while serving the Saxon court, Mengs maintained a strong presence in Rome. His connections within the city's artistic and intellectual circles continued to grow. In 1754, his standing was further recognized when he was appointed director of the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's prestigious academy of art. This position placed him at the center of artistic education and discourse in the city, allowing him to further promote his Neoclassical principles among aspiring artists.

Roman Masterworks: Parnassus and Beyond

The culmination of Mengs's first extended Roman period, and arguably his most famous work, is the ceiling fresco Parnassus, completed in 1761 for the gallery of Villa Albani (now Villa Torlonia) in Rome. Commissioned by Cardinal Alessandro Albani, a prominent collector and patron of Winckelmann, the fresco is widely regarded as a manifesto of Neoclassicism.

Depicting Apollo Belvedere at the center, surrounded by Mnemosyne and the nine Muses, the composition is a deliberate departure from the dynamic, illusionistic ceiling paintings of the Baroque tradition, exemplified by artists like Pietro da Cortona or Andrea Pozzo. Mengs opted for a clear, frieze-like arrangement, reminiscent of classical reliefs and Raphael's own Parnassus in the Vatican. The figures are statuesque, idealized, and rendered with precise drawing and cool, clear colors. The work embodies Winckelmann's ideals of "noble simplicity and calm grandeur," prioritizing order, balance, and idealized beauty over dramatic movement and emotional intensity. It became a landmark, signaling a definitive shift in aesthetic taste.

Another significant work from this period is the Apotheosis of St. Eusebius, a ceiling fresco in the church of Sant'Eusebio in Rome. While still employing some Baroque compositional devices, it demonstrates Mengs's move towards greater clarity and classical restraint compared to earlier ceiling paintings. These major commissions solidified his reputation as the leading painter in Rome and a champion of the new Neoclassical style.

Rivalry and Recognition in Rome

The art world of eighteenth-century Rome was vibrant and competitive. Mengs's primary rival, particularly in the lucrative field of portraiture, was the Italian painter Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787). Batoni was a master of the late Rococo and early Neoclassical styles, renowned for his elegant portraits, especially of Grand Tourists visiting Rome. He depicted his sitters often surrounded by classical antiquities, creating images that were both sophisticated and informative.

Mengs and Batoni represented slightly different artistic paths. While both engaged with classicism, Batoni retained more of the Rococo charm and painterly richness, whereas Mengs pursued a more rigorous, archaeologically informed Neoclassicism, emphasizing line and idealized form, influenced by his association with Winckelmann. Both artists were highly successful and sought after by patrons, including royalty and nobility from across Europe. Their rivalry spurred each other on, contributing to the high quality of painting produced in Rome during this period. Ultimately, Mengs's stricter adherence to Neoclassical principles and his theoretical writings perhaps gave him an edge in being perceived as the leader of the new movement. His connections, particularly through Winckelmann and later the Spanish court, also helped secure major commissions.

Summons to the Spanish Court

In 1761, Mengs's international fame reached its zenith when he was summoned to Madrid by King Charles III of Spain. Charles III, an enlightened monarch keen on modernizing Spain and embellishing his capital, appointed Mengs as his Primer Pintor de Cámara (First Court Painter), offering him a substantial salary. This marked the beginning of a significant, albeit sometimes challenging, phase of Mengs's career.

His primary task in Madrid was the decoration of the Palacio Real (Royal Palace). He was commissioned to paint several large ceiling frescoes, continuing the decorative program initiated earlier by artists like Corrado Giaquinto. Mengs brought his Neoclassical style to the Spanish court, creating works such as the Apotheosis of Hercules and Aurora in the palace ceilings. These frescoes, while grand in scale, aimed for greater compositional clarity and classical dignity than the works of his predecessors.

His time in Madrid was not without difficulties. The Spanish climate reportedly affected his health. He also faced court intrigue and potential rivalry from established Spanish artists and the lingering influence of the great Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who was also working in the palace until his death in 1770. Despite these challenges, Mengs enjoyed the King's favor and produced a significant body of work, including numerous portraits of the royal family and Spanish nobility. His presence profoundly impacted the Spanish art scene, introducing Neoclassicism and influencing a generation of Spanish artists, most notably the young Francisco Goya.

Interludes in Italy and Later Years

Due to recurring health problems, Mengs sought permission from Charles III to return to the warmer climate of Italy. He spent the years 1771 to 1774 primarily in Florence and Rome. During this period, he continued to paint, including portraits of members of the Habsburg court in Florence and completing commissions he had outstanding. He also revisited his theoretical work and reconnected with the artistic community in Rome.

One important friendship from this period was with the Spanish diplomat and scholar José Nicolás de Azara, who was also a friend of Winckelmann. Mengs painted a notable portrait of Azara, capturing his intellectual intensity and refined character, demonstrating Mengs's continued mastery of portraiture alongside his large-scale decorative work.

Mengs returned to Madrid in 1774, resuming his duties as First Court Painter. However, his health remained fragile, and his productivity may have lessened compared to his first Spanish period. He completed further works for the Royal Palace and continued to exert influence over the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. His final years were marked by declining health and perhaps a sense of weariness from the demands of court life. He eventually returned to Rome in 1777, where he died two years later, on June 29, 1779, at the age of 51. He died in relative poverty, despite his fame and high appointments, burdened by debts and the needs of his large family.

Artistic Style and Theoretical Synthesis Revisited

Mengs's artistic style is often characterized as eclectic, a term he himself might have embraced. He consciously sought to synthesize what he considered the best qualities of various masters: the design and expression of Raphael, the grace and chiaroscuro of Correggio, the color and naturalism of Titian, all refined through the lens of classical Greek sculpture's idealized forms. This approach was central to his theoretical writings and his artistic practice.

His emphasis was on disegno – not just drawing in the narrow sense, but the intellectual conception and structuring of a work of art. Clarity of composition, balanced forms, smooth finish, and idealized figures were hallmarks of his style. He moved away from the dynamic asymmetry, dramatic lighting, and overt emotionalism of the Baroque, as seen in the works of Gian Lorenzo Bernini or Pietro da Cortona, and rejected the perceived frivolity and decorative excess of the Rococo, exemplified by French painters like François Boucher or Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

However, Mengs was not entirely divorced from the traditions he sought to reform. Especially in his ceiling frescoes, elements of Baroque composition and grandeur persist. Some critics, both then and now, have found his work learned and technically brilliant but sometimes lacking in emotional warmth or spontaneity, appearing overly calculated or "cold." This led to debates about his true place – was he the first Neoclassicist or the last academic painter working within a reformed Baroque tradition? Regardless, his commitment to classical ideals and his systematic approach profoundly shaped the Neoclassical movement.

Controversies and Personal Challenges

Despite his professional success, Mengs's life was not without controversy and personal hardship. His conversion to Catholicism, while perhaps strategically astute, was viewed critically by some in Protestant Northern Europe. His artistic dominance also bred jealousy. Sources mention friction within papal circles and rivalry with other artists, potentially hindering some commissions or relationships. The anecdote about a conflict with "St. Silvester" likely refers to jealousy or disputes over commissions or honors related to the papacy or associated orders.

His pursuit of classical ideals sometimes clashed with contemporary sensibilities. A reported incident involving a nude study in Vienna allegedly caused a minor scandal, highlighting the tension between academic artistic practice (drawing from the nude figure was essential training) and public decorum, even as artists championed the idealized nude forms of antiquity.

Furthermore, Mengs struggled with financial difficulties throughout much of his life. Despite high salaries from the Saxon and Spanish courts, the costs of maintaining a large family, managing studios in different cities, and perhaps his own financial management led to persistent debt. His personal life also seems to have been complex, with accounts suggesting a strained relationship with his wife, possibly exacerbated by household tensions and his frequent travels and illnesses. These personal struggles paint a picture of a man burdened by worldly concerns even as he pursued lofty artistic ideals.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Anton Raphael Mengs's influence on the course of European art was substantial and multifaceted. He was arguably the most important painter in the transition from Rococo to Neoclassicism, providing both exemplary artworks and a coherent theoretical basis for the new style. His Parnassus remains a landmark painting, embodying the core tenets of the movement.

His impact was felt geographically across Europe. His work in Dresden, Rome, and Madrid placed him at the center of artistic developments in Germany, Italy, and Spain. As First Court Painter in Spain, he played a crucial role in introducing Neoclassicism there, directly influencing Spanish artists, including the young Francisco Goya (1746-1828), who would later develop his own unique and powerful style but whose early work shows Mengs's imprint.

Mengs was also an influential teacher and mentor. As director of the Accademia di San Luca and through his personal studio, he guided numerous students. His pupils and followers helped disseminate his style and principles throughout Europe, holding positions in academies in cities like Vienna and Copenhagen. Artists who were part of the broader Neoclassical movement in Rome, even if not direct pupils, certainly knew his work and theories. This includes figures like the French master Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), who arrived in Rome shortly before Mengs's death and became the leading figure of French Neoclassicism. Others associated with the Roman Neoclassical milieu, such as the Italian Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844), the American Benjamin West (1738-1820), the Swiss Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), and the British artists John Flaxman (1755-1826) and Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798), were all part of the environment shaped by Mengs and Winckelmann.

His legacy is complex. While admired for his technical skill, intellectual rigor, and pivotal role in establishing Neoclassicism, his reputation fluctuated after his death. Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion and individualism, reacted against Neoclassical rationalism, and Mengs's work was sometimes criticized as academic and lacking passion. However, art history recognizes his crucial role as a bridge figure, a synthesizer of traditions, and a defining artist of the Enlightenment era. His paintings continue to be studied for their technical mastery and their embodiment of Neoclassical ideals, and his writings remain important documents of eighteenth-century art theory.

Conclusion

Anton Raphael Mengs navigated the complex artistic world of the eighteenth century with remarkable skill and intellectual force. From his rigorous early training under his father, Ismael Mengs, to his formative years in Rome absorbing the lessons of antiquity and the Renaissance masters like Raphael and Correggio, he forged a distinct artistic identity. His crucial friendship with Johann Joachim Winckelmann solidified his commitment to Neoclassicism, making him a leading visual proponent of the movement's ideals. Serving the courts of Dresden and Madrid, and working alongside or in competition with contemporaries like Pompeo Batoni and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Mengs produced landmark works like Parnassus that defined the new aesthetic. Despite personal challenges and controversies, his influence, disseminated through his art, his theoretical writings, and his impact on pupils like Goya and contemporaries like David and Kauffman, was profound and lasting. He remains a central figure for understanding the profound shift in European art and thought during the Age of Enlightenment.