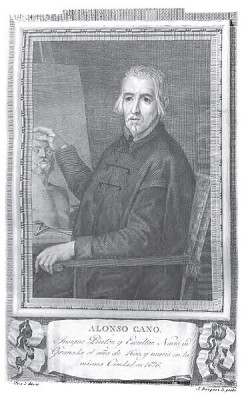

Alonso Cano (1601-1667) stands as one of the most compelling and multifaceted figures of the Spanish Golden Age. A supremely gifted painter, sculptor, and architect, his prodigious talent across disciplines earned him the laudatory, though perhaps slightly hyperbolic, title of the "Spanish Michelangelo." Born in Granada, his career unfolded primarily in the vibrant artistic centers of Seville and Madrid before he returned to his native city for his final years. Cano's life was as tumultuous and dramatic as the Baroque era itself, marked by artistic triumphs, influential friendships, courtly favour, and startling controversies, yet his work often resonates with a classical serenity and profound spiritual depth that belies the chaos of his personal biography. His legacy is cemented not only by the individual masterpieces he created but also by his significant influence on the trajectory of Spanish art in the 17th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Granada and Seville

Alonso Cano Almansa entered the world in Granada on March 19, 1601. His artistic inclinations were likely nurtured from a young age, as his father, Miguel Cano, was a respected ensamblador – a designer and assembler of the elaborate carved wooden altarpieces (retablos) that were central features in Spanish churches. This familial background provided Alonso with foundational knowledge of woodcarving, design principles, and the intricate relationship between sculpture, painting, and architectural settings inherent in these large-scale commissions. This early exposure undoubtedly laid the groundwork for his later versatility.

Around 1614 or 1615, the Cano family relocated to Seville, then the undisputed artistic capital of Spain and a bustling hub of commerce and culture. It was here that the young Alonso received his formal artistic training. He entered the workshop of Francisco Pacheco, a painter, theorist, and influential teacher whose studio was a crucible for emerging talent. Pacheco, known for his somewhat dry, academic style but also for his intellectual rigour and connections, provided Cano with instruction in painting and drawing. Pacheco's role as an art censor for the Inquisition also meant his workshop emphasized decorum and correct iconography in religious art.

Crucially, Pacheco's studio was also where Cano likely first encountered Diego Velázquez, who was Pacheco's most famous pupil and later his son-in-law. Although Velázquez was slightly older, the two young artists formed a close and enduring friendship during these formative years in Seville, a bond that would prove significant later in Cano's career. While studying painting with Pacheco, Cano simultaneously honed his skills as a sculptor under the tutelage of Juan Martínez Montañés, the leading sculptor in Seville, renowned for his realistic and emotionally resonant polychrome wood figures. This dual apprenticeship under the masters of Seville's painting and sculpture scenes was exceptional and equipped Cano with a rare mastery of both arts. By 1626, Cano had passed his examination and was certified as a master painter, ready to embark on his independent career.

The Seville Period: Establishing a Reputation

Having completed his training, Alonso Cano quickly established himself as an independent master in Seville. His early works from this period demonstrate the influences of his teachers but also reveal his burgeoning individual style. He collaborated with his father on altarpiece projects, often providing the paintings and sculptures that adorned the architectural structures Miguel Cano designed. His technical proficiency, particularly in drawing, was evident early on, forming the backbone of his compositions in both painting and sculpture.

During his Seville years (roughly 1626-1638), Cano competed for commissions alongside established figures and rising stars. The artistic environment was rich and competitive, dominated by the intense realism and dramatic chiaroscuro favoured by artists like Francisco de Zurbarán, another giant of the Seville school known for his powerful monastic portraits and still lifes. While Cano absorbed the prevailing Baroque tendencies towards naturalism and emotional intensity, his work began to distinguish itself through a greater emphasis on idealized beauty, graceful lines, and a more balanced, almost classical sense of composition, possibly reflecting an innate preference or early exposure to Italian Renaissance prints.

Key works from this early phase include commissions for various churches and convents in and around Seville. For instance, the sculptures for the altarpiece of St. John the Evangelist in the Church of Santa Paula (now dispersed) showcased his skill. His Madonna and Child sculpture for the Church of Santa Maria de Lebrija (Nebrija) is another significant work from this time, demonstrating the influence of Montañés in its technical execution but hinting at Cano's own developing sense of grace and idealized form. He gained recognition for his ability to convey deep religious sentiment through elegant and harmonious figures, setting him apart from the starker realism of some contemporaries.

Madrid and Royal Patronage: A New Stage

Around 1638, Alonso Cano made a pivotal move from Seville to Madrid, the political and royal heart of Spain. This relocation was likely encouraged, if not directly facilitated, by his friend Diego Velázquez, who was by then firmly established as the leading painter at the court of King Philip IV. The move opened up new opportunities for patronage and exposed Cano to the vast royal art collections, which were rich in works by Italian Renaissance masters, particularly the Venetians like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto.

In Madrid, Cano entered the service of the powerful Count-Duke of Olivares, Philip IV's chief minister, and also received commissions directly from the Crown. He collaborated with Velázquez on decorative projects, including the decoration of the Hall of Mirrors (Salón de los Espejos) in the Alcázar of Madrid, though much of this work was lost in the fire of 1734. His talents were recognized to the extent that he was appointed drawing master to the heir to the throne, Prince Baltasar Carlos, a prestigious position, although the prince's early death curtailed this role.

Working in Madrid allowed Cano to refine his style further. Exposure to the Venetian masters in the royal collection seems to have influenced his use of colour, leading to a richer, more luminous palette compared to the more restrained tones often seen in Seville. He continued to work across disciplines, undertaking painting commissions, designing sculptural elements, and even contributing architectural ideas. His reputation grew, though his notoriously difficult temperament sometimes complicated his relationships with patrons and colleagues. He worked alongside other court artists, including painters like Joaquín Pallares and sculptors such as Bernabé Contreras, contributing to various royal and ecclesiastical projects in the capital and surrounding areas, like the altarpiece for the church in Getafe.

The Painter: Style and Masterpieces

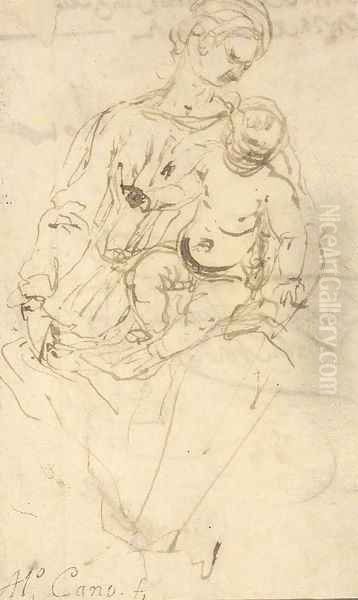

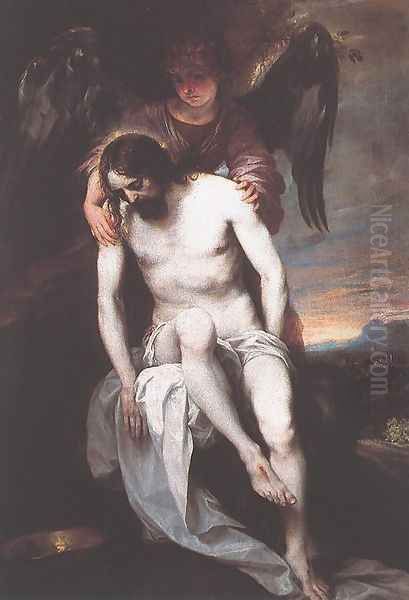

Alonso Cano's painting is characterized by a distinctive synthesis of Baroque dynamism and an underlying classical structure and idealism. While he could employ dramatic lighting and compositions when the subject demanded it, his figures often possess a grace, elegance, and emotional restraint that distinguishes his work from the more overt theatricality of some Baroque contemporaries. His superb draughtsmanship provided a firm foundation for his paintings, evident in the clear contours and well-defined forms of his figures.

His colour palette evolved, particularly after his move to Madrid, becoming richer and more nuanced, influenced by the Venetian painters he admired, especially Titian and Veronese. He mastered the use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), but often preferred softer transitions and a more diffused light than the stark tenebrism associated with artists like Jusepe de Ribera or early Velázquez. This contributes to the sense of serenity and harmony found in many of his religious scenes.

Among his most celebrated paintings are works like the Vision of St. John the Evangelist: The Vision of Jerusalem (c. 1636-37, Wallace Collection, London and a version possibly in the Louvre, Paris), which showcases his ability to handle complex compositions and ethereal light. His depictions of the Immaculate Conception (a recurring theme, with a notable version from 1655-56) are renowned for their delicate beauty and serene spirituality, becoming influential models for later artists like Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. The Crucifixion (various versions, e.g., Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid) demonstrates his capacity for conveying profound pathos within a balanced, almost sculptural composition. Other significant paintings include Noli me tangere (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest), The Miracle of the Well (Prado Museum, Madrid, depicting a miracle of St. Isidore), and Christ's Descent into Limbo (Los Angeles County Museum of Art). His portraits, though less numerous, also show his skill in capturing likeness and character.

The Sculptor: Precision and Grace

While perhaps more famous as a painter during his lifetime, Alonso Cano was also a sculptor of exceptional talent. His training under Montañés provided him with impeccable technique in wood carving, the dominant medium for sculpture in Spain. However, Cano developed a distinct sculptural style that moved towards greater idealization and classical grace compared to the sometimes intense, almost raw realism of his master. His figures often exhibit smooth surfaces, elegant postures, and a sense of calm dignity, even in moments of religious ecstasy or suffering.

He specialized in polychrome wood sculpture, where the carved figure was meticulously painted to enhance its lifelikeness and emotional impact. Cano often designed entire altarpieces (retablos), integrating his sculptures seamlessly with the architectural framework and sometimes accompanying paintings. His understanding of both disciplines allowed him to create unified artistic statements.

Key sculptural works include the exquisite Immaculate Conception housed in the sacristy of Granada Cathedral, a small but powerful figure radiating serene divinity. His statues of St. John the Baptist (various locations) and St. Anthony of Padua (versions in Munich and elsewhere) are noted for their refined modelling and gentle expressiveness. The figures of St. Peter and St. Paul created for Granada Cathedral further exemplify his mature sculptural style. Though his surviving sculptural output is not as extensive as his paintings, the quality is consistently high, marking him as one of the most important Spanish sculptors of the 17th century, bridging the gap between the realism of Montañés and the later, more dynamic Baroque styles. His ability to imbue wood with a sense of soft flesh and flowing drapery was remarkable.

The Architect: Vision in Stone

Alonso Cano's talents extended impressively into the realm of architecture, a field in which he demonstrated both innovative thinking and a deep understanding of classical principles adapted to the Baroque sensibility. While not solely an architect by profession, his contributions, particularly in Granada, were highly significant. His background as the son of an ensamblador and his work designing complex altarpieces provided him with a strong sense of structure, proportion, and spatial design.

His most famous architectural achievement is undoubtedly the main façade of Granada Cathedral, designed late in his life (constructed after his death, from 1667 onwards). Faced with the challenge of completing a cathedral begun in the Gothic and Renaissance periods, Cano conceived a highly original design. Instead of a conventional façade, he created a monumental triumphal arch structure, using three deeply recessed arches that correspond to the nave and aisles within. This innovative solution masterfully masked the differing heights of the interior spaces and created a powerful, theatrical entrance. The façade blends classical elements with Baroque dynamism, showcasing Cano's ability to synthesize styles and create something entirely new. It remains one of the most iconic examples of Spanish Baroque architecture.

Beyond Granada Cathedral, Cano was involved in other architectural projects, though documentation is sometimes sparse. He provided designs for church portals, chapels, and temporary structures (like triumphal arches for royal entries). His work often shows a preference for clear geometric forms combined with rich, but controlled, sculptural decoration. His architectural vision, like his painting and sculpture, aimed for a balance between grandeur and harmony, contributing significantly to the architectural landscape of the cities where he worked, particularly Granada.

A Turbulent Life: Controversy and Character

Despite the elegance and serenity often found in his art, Alonso Cano's personal life was marked by turbulence and a notoriously volatile temperament. Anecdotes abound regarding his pride, impatience, and propensity for conflict. One famous story, possibly apocryphal but illustrative of his reputation, tells of him smashing a statue of a saint he had just completed because the patron (reputedly an oidor, or judge) haggled over the price, declaring he could make gods but would not be treated disrespectfully. This alleged act of iconoclasm, even if exaggerated, points to a man of fierce artistic pride and a short fuse.

More serious controversies plagued his career. His move from Seville to Madrid in 1638 is sometimes attributed to his having fled after wounding another painter, Sebastián de Llanos y Valdés, in a duel, though the exact circumstances remain unclear. The most dramatic and damaging episode occurred in 1644 in Madrid. His wife, María Magdalena de Uceda Paredes (his second wife), was found murdered in their home, stabbed fifteen times. Cano himself discovered the body upon returning home. An Italian servant had disappeared, along with a sum of money, making him the prime suspect. However, Cano himself was arrested and accused of the crime. He was subjected to torture (reportedly the water torture, tortura del agua), but maintained his innocence and, according to accounts, his right arm (his painting arm) was spared. Eventually, lacking sufficient evidence or perhaps through the intervention of influential friends, he was acquitted, but the scandal cast a long shadow.

His difficult personality also led to conflicts in his professional life. While working at Granada Cathedral later in life, he clashed repeatedly with the cathedral chapter over artistic and financial matters. His refusal at one point to sculpt a crucifix demanded by the chapter led to his temporary suspension from his position. These incidents paint a picture of a brilliant but deeply flawed individual, whose artistic genius coexisted with a challenging and often self-destructive character.

Return to Granada and Later Years

In 1652, seeking perhaps refuge or a return to his roots, Alonso Cano moved back to his native Granada. He secured the position of racionero (prebendary, a salaried benefice holder) at Granada Cathedral, a role that provided financial stability but also entangled him further in ecclesiastical politics. His relationship with the cathedral chapter remained fraught with tension. Disputes over his duties, payments, and artistic decisions were frequent. To solidify his position and protect himself from further secular prosecution or ecclesiastical censure, Cano took the surprising step of being ordained as a priest in 1658, though his commitment to clerical duties seems to have been secondary to his artistic pursuits.

Despite the ongoing conflicts, his final period in Granada was artistically productive. It was during these years that he conceived the groundbreaking design for the cathedral's façade. He continued to paint and sculpt, producing mature works that often displayed a heightened spirituality and a refined, almost ethereal quality. His influence on the local art scene was profound, establishing what became known as the Granada school of painting. He mentored younger artists, most notably Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra and Juan de Sevilla, who carried forward elements of his style, characterized by idealized figures, soft modelling, and harmonious compositions.

Cano remained fiercely independent and critical to the end. A famous anecdote recounts that on his deathbed in 1667, he refused a crucifix offered to him by a priest because he considered it poorly carved, demanding a simple, unadorned cross instead. He died on September 3, 1667, and was buried, fittingly, in Granada Cathedral, the building he had so significantly shaped. He left behind unfinished projects and a complex legacy as both a revered artist and a controversial figure.

Contemporaries and Influence

Alonso Cano operated within a rich network of artistic relationships, rivalries, and influences that shaped his career and the broader landscape of Spanish Baroque art. His teachers, Francisco Pacheco and Juan Martínez Montañés, provided his foundational training in Seville's dominant styles. His lifelong friendship with Diego Velázquez was crucial, offering mutual support and likely facilitating Cano's entry into Madrid's court circles. While their styles diverged – Velázquez pursuing profound naturalism and psychological depth, Cano leaning towards idealized grace – their shared background and ongoing connection were significant.

In Seville, Cano worked alongside Francisco de Zurbarán, whose stark realism and intense spirituality offered a contrast to Cano's developing classicism. Later, the rise of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, known for his softer, sweeter religious scenes and genre paintings, would further shape the Seville school, with Murillo arguably absorbing some influence from Cano's idealized figures and compositions. In Madrid, Cano encountered the work of court painters and was exposed to the legacy of earlier Spanish masters like El Greco, whose elongated figures and expressive colour might have offered a different model of artistic intensity.

The influence of Italian art was paramount, absorbed both through prints and, more directly, through the royal collections in Madrid. The Venetian masters Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto impacted his use of colour and light. The High Renaissance ideals of Raphael and the powerful forms of Michelangelo (earning him the "Spanish Michelangelo" moniker for his versatility) provided classical touchstones. He may also have been aware of contemporary Italian Baroque artists like Guido Reni or Domenichino, whose classicizing tendencies resonated with his own inclinations. His relationship with Sebastián de Herrera Barnuevo, another versatile artist active in Madrid, developed into a deep friendship. In Granada, his legacy was directly transmitted through pupils like Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra and Juan de Sevilla. Cano's unique blend of Spanish realism, Italian classicism, and Baroque sensibility made him a pivotal figure, influencing the direction of painting, sculpture, and architecture in Spain.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Alonso Cano is unequivocally recognized as a major master of the Spanish Golden Age, a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing. His unique position stems from his exceptional proficiency across the three major visual arts: painting, sculpture, and architecture. The title "Spanish Michelangelo," while perhaps an overstatement of parity with the Florentine titan, accurately reflects this remarkable versatility, which was rare even in an era that valued multifaceted talent.

In painting, he offered a distinct alternative to the dominant modes of intense realism (Zurbarán, Ribera) or courtly naturalism (Velázquez). His work introduced a strain of idealized beauty, classical balance, and serene elegance into Spanish Baroque art, particularly influential in religious imagery. His depictions of the Immaculate Conception and tranquil Holy Families provided models that resonated deeply within Spanish piety and influenced subsequent generations, notably Murillo.

As a sculptor, he refined the polychrome wood tradition inherited from Montañés, infusing it with greater grace and subtlety. His sculptures are prized for their technical perfection and quiet emotional power. Though fewer in number than his paintings, they represent a significant contribution to Spanish Baroque sculpture.

In architecture, his design for the façade of Granada Cathedral stands as a landmark achievement, a bold and innovative solution that became a defining monument of the Spanish Baroque style. It showcases his ability to think spatially and structurally on a grand scale, integrating architectural form with sculptural sensibility.

His works are now housed in major museums across the world, including the Prado Museum in Madrid (which holds a significant collection), the Louvre in Paris, the Wallace Collection in London, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, as well as in numerous churches and collections in Spain, particularly in Seville and Granada.

Despite the controversies of his life and his difficult personality, Alonso Cano's artistic legacy is secure. He was a pivotal figure who navigated the complex currents of the Spanish Baroque, forging a unique style that blended technical mastery, classical ideals, and profound religious feeling. His influence extended through his pupils and his works, cementing his status as one of the indispensable artists of Spain's Siglo de Oro.