Introduction: A Spanish Master in Naples

Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652), known affectionately and sometimes formidably in Italy as "Lo Spagnoletto" (The Little Spaniard), stands as a towering figure of the Baroque era. Born in Xàtiva, near Valencia, Spain, Ribera spent the vast majority of his highly successful artistic career in Naples, then a vibrant and crucial part of the Spanish Empire. He became the leading painter in the city for decades, skillfully merging the intense, dramatic realism he absorbed from Caravaggio and his followers in Italy with his innate Spanish sensibility for profound emotion and tangible reality. Ribera was not only a master painter but also a gifted draftsman and one of the most significant printmakers of his time, whose works profoundly influenced artists across Europe.

Early Life and Training in Spain

Jusepe de Ribera, baptized Juan José de Ribera, entered the world in Xàtiva, Valencia, in 1591. While later romantic accounts, often unreliable, attempted to link him to nobility, perhaps even suggesting descent from Charles V, historical records point to a more modest background. His father was likely a shoemaker, a respectable trade but far removed from aristocratic circles. These unfounded legends speak more to the impact Ribera later made than to his actual origins.

The crucial formative period of his youth was spent in Valencia, where he entered the workshop of Francisco Ribalta (c. 1565–1628). Ribalta was a significant Spanish painter in his own right, one of the first in Spain to adopt a form of tenebrism – the dramatic use of light and shadow – likely influenced by Italian art, possibly even early works of Caravaggio seen through prints or other intermediaries. Training under Ribalta provided Ribera with a solid foundation in drawing and painting techniques and exposed him early on to the expressive potential of dramatic lighting, a feature that would become central to his own mature style. This apprenticeship laid the groundwork for his later artistic explorations.

The Italian Journey: Rome, Caravaggio, and Tenebrism

Sometime before 1611, likely around 1610, the ambitious young Ribera left Spain for the artistic heartland: Italy. His exact movements initially are not perfectly documented, but he is known to have spent time in Northern Italy, possibly visiting Parma to study the works of Correggio, known for his soft sfumato and dynamic compositions. However, the most transformative phase of his Italian journey occurred in Rome. The Eternal City was then buzzing with the legacy of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), who had revolutionized painting with his uncompromising realism and radical use of chiaroscuro, often pushed to the extreme form known as tenebrism.

Though Caravaggio himself had died shortly before or around the time Ribera arrived in Rome, his powerful influence permeated the city's artistic scene. Ribera deeply absorbed the lessons of Caravaggio and his followers, the Caravaggisti. He embraced the stark contrasts between deep shadow and brilliant light, using it to create intensely dramatic and emotionally charged scenes. He adopted the practice of painting directly from life, often using ordinary people as models for saints and heroes, lending his figures an unprecedented sense of physical presence and psychological depth. In Rome, he would have encountered the works, and possibly the persons, of prominent Caravaggisti, both Italian and Northern European, such as Gerrit van Honthorst, Hendrik ter Brugghen, and perhaps others like Bartolomeo Manfredi or the French painter Simon Vouet, further solidifying his commitment to this powerful new style.

Settling in Naples: The Heart of a Career

By 1616, Ribera had moved south to Naples. This move proved decisive for his life and career. Naples, at the time, was not just a major Italian city but the capital of a Spanish Viceroyalty, a bustling metropolis teeming with artistic opportunities, Spanish administrators, and wealthy patrons, both secular and ecclesiastical. It was a place where a talented Spanish artist could thrive, benefiting from connections to the ruling power while immersing himself in a rich Italian artistic environment.

Shortly after arriving, Ribera married Caterina Azzolino, the daughter of a reasonably well-established Neapolitan painter, Giovanni Bernardo Azzolino (c. 1572–c. 1645). This marriage likely provided Ribera with valuable connections within the local artistic community and society, helping him secure commissions and establish his workshop. His talent, however, was the primary driver of his rapid ascent. He quickly gained the favour of the Spanish Viceroys, including the Duke of Osuna, the Duke of Alcalá, and later the Count of Monterrey, who became major patrons, commissioning numerous works for themselves and for the Spanish crown. The local nobility and powerful religious orders also sought out his work, ensuring a steady stream of prestigious commissions. Ribera became the undisputed leading painter in Naples, a position he held for much of his life.

Artistic Style: Realism, Drama, and Tactile Surfaces

Ribera's mature style is a compelling synthesis of Spanish realism and Italian Baroque drama, heavily indebted to Caravaggio but uniquely his own. Tenebrism remained a hallmark: figures often emerge dramatically from deep, dark backgrounds, illuminated by a stark, raking light that sculpts forms and heightens the emotional intensity. This wasn't merely a stylistic trick; it focused the viewer's attention, emphasized the spiritual or psychological core of the scene, and created a palpable sense of immediacy.

His commitment to realism was profound and sometimes shocking to contemporaries. Ribera rarely idealized his figures. Saints, philosophers, and mythological characters often bear the marks of age, toil, and suffering. Wrinkles are deeply etched, skin can appear weathered or bruised, muscles strain, and bodies show imperfections. This unflinching naturalism made his religious figures feel intensely human and relatable, aligning with the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on piety and direct emotional engagement. He rendered textures with extraordinary skill – the rough sackcloth of a hermit, the soft vulnerability of aged skin, the cold gleam of metal armour, the crisp pages of a book – giving his paintings a remarkable tactile quality. His brushwork could vary from rough and vigorous in early works to more refined and blended in later periods, always serving the expressive needs of the subject. While often dominated by earthy tones and dramatic shadows, his palette could also incorporate rich reds, blues, and golds, particularly in his later works.

Themes and Subjects: Saints, Sinners, and Philosophers

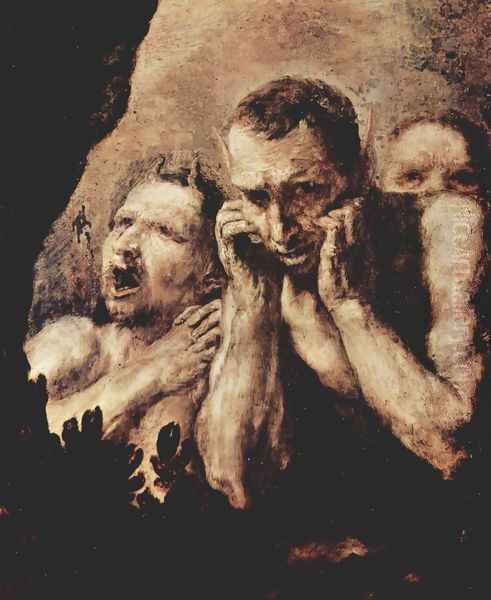

Ribera's subject matter ranged widely, but certain themes recurred throughout his career, reflecting his own interests and the demands of his patrons. Religious subjects dominated his output, particularly scenes of martyrdom and penitent saints. He depicted the suffering of figures like Saint Bartholomew (flayed alive), Saint Sebastian (pierced by arrows), and Saint Andrew (crucified) with a visceral intensity that could be both horrifying and deeply moving. These works explored themes of faith tested by extreme physical torment.

Equally common were his portrayals of penitent saints contemplating mortality and divine mercy, such as Saint Jerome (often shown translating the Bible in the wilderness, sometimes visited by an angel), Saint Mary Magdalene, and Saint Peter. These images emphasized introspection, piety, and the human struggle with sin and redemption. He also painted numerous depictions of the Holy Family, often imbued with a tender humanity, as seen in The Holy Family with Saints Anne and Catherine of Alexandria (1648).

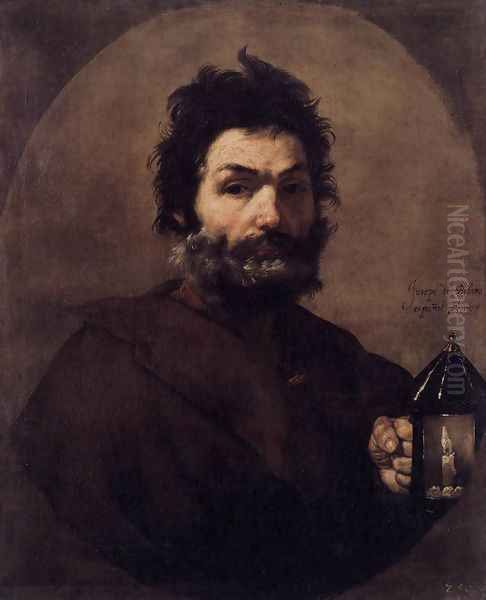

Beyond traditional religious iconography, Ribera showed a marked interest in depicting philosophers and ancient figures, often portrayed as rugged, ascetic individuals, blurring the line between historical portraiture and genre scenes. His Diogenes (1637) is a famous example, showing the philosopher with his lantern, rendered with the same earthy realism as his saints. He also tackled mythological subjects, often choosing moments of violence or intense emotion, such as Apollo and Marsyas or the Drunken Silenus, treating these classical themes with his characteristic realism rather than idealized classicism. Ribera also produced striking portraits and allegorical series, like his paintings representing the Five Senses, which further demonstrate his keen observation of human types and physical reality. The Clubfoot (1642), depicting a boy with a deformed foot yet a hopeful expression, is a masterpiece of empathetic realism.

Master of Printmaking: Etchings and Influence

While primarily celebrated as a painter, Jusepe de Ribera was also one of the most accomplished printmakers of the 17th century, working primarily in the technique of etching. Although his output in this medium was relatively small compared to his painted oeuvre – only a few dozen plates are known – the quality and originality of his prints are exceptional. His etchings display the same powerful draughtsmanship, dramatic lighting, and intense realism found in his paintings.

Subjects in his prints often mirrored those in his paintings: suffering saints, expressive heads, mythological figures, and anatomical studies. Works like The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew and studies of heads and ears showcase his technical virtuosity and his ability to translate the tonal richness and emotional power of his paintings into the linear medium of etching. These prints were crucial in disseminating Ribera's style far beyond Naples. They circulated widely across Europe, influencing artists who may never have seen his paintings firsthand. Notably, Rembrandt van Rijn in Amsterdam owned and admired Ribera's etchings, and their impact can be discerned in the Dutch master's own work. Ribera's prints solidified his reputation and extended his artistic reach significantly.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Ribera's prolific career produced numerous masterpieces, many of which reside in major museums worldwide. Among his most representative and celebrated works are:

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (various versions, e.g., c. 1634, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): A signature theme, depicted with harrowing realism and intense pathos, showcasing Ribera's mastery of anatomy and dramatic composition.

Saint Jerome (numerous versions, e.g., with the Angel, c. 1626, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples): Often shown as a rugged scholar in the wilderness, embodying penitence and intellectual devotion. The Capodimonte version highlights the dramatic encounter with the divine messenger.

Diogenes (1637, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden): A powerful portrayal of the Cynic philosopher, rendered as a weathered but dignified figure, exemplifying Ribera's interest in classical themes treated realistically.

The Clubfoot (The Boy with a Club Foot) (1642, Musée du Louvre, Paris): An iconic work of realism and empathy, capturing the boy's physical disability alongside his cheerful resilience. The note he carries asks for alms "for the love of God."

The Holy Family with Saints Anne and Catherine of Alexandria (1648, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): A later work showing a potential shift towards slightly softer lighting and richer colours, while retaining his characteristic human warmth.

Lamentation over the Dead Christ (e.g., early 1620s version, National Gallery, London): A deeply moving depiction of grief, showcasing his ability to convey profound emotion through gesture and expression, heavily influenced by Caravaggio's tenebrism.

Allegory of Touch (c. 1632, Museo del Prado, Madrid): Part of a series on the Five Senses, this painting of a blind sculptor feeling a classical head is a remarkable exploration of sensory experience and realism.

Drunken Silenus (1626, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples): A mythological scene treated with earthy, almost grotesque realism, depicting the tutor of Bacchus surrounded by revellers in a distinctly unclassical manner.

Apollo and Marsyas (versions e.g., 1637, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples & Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels): A brutal mythological subject depicting the flaying of the satyr Marsyas by the god Apollo, rendered with chilling detail and psychological intensity.

Saint Andrew (c. 1630-32, Museo del Prado, Madrid): A powerful image of the aged apostle, often shown before his martyrdom, embodying steadfast faith and physical presence.

These works, among many others, demonstrate the range of Ribera's subjects, his consistent technical brilliance, and his profound engagement with the human condition, whether in moments of ecstasy, suffering, or quiet contemplation. Major collections of his work can be found in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, and the Louvre in Paris, among others.

Ribera's Workshop and Influence

As the preeminent painter in Naples for several decades, Ribera maintained a large and active workshop to help meet the high demand for his work. He trained numerous pupils and employed assistants who helped with preparatory work, replicas, and variations of his popular compositions. His powerful style, characterized by dramatic tenebrism and intense realism, became the dominant trend in Neapolitan painting for much of the 17th century.

Among his most notable students were Luca Giordano (1634-1705), who started in Ribera's workshop and became one of the most prolific and famous Italian Baroque painters, known for his speed and versatility, though he later moved towards a lighter, more decorative style. Francesco Fracanzano (1612-1656) was another significant pupil who closely followed Ribera's naturalistic style. Other artists associated with his circle or influenced by him include Aniello Falcone (known for his battle scenes) and the Master of the Annunciation to the Shepherds.

While Ribera's influence was immense, some accounts suggest he could be critical of students who merely copied his manner without grasping the underlying principles or developing their own vision. Nevertheless, his impact shaped the Neapolitan school profoundly. Even later major Neapolitan artists like Mattia Preti (who worked in Naples after Ribera's death but was clearly indebted to him) and Francesco Solimena operated within the artistic lineage he had established. His influence extended back to Spain as well, as many of his works were sent there, impacting painters like Francisco de Zurbarán and the young Diego Velázquez.

Contemporaries and Artistic Circle

Throughout his career, Ribera interacted with, competed against, and influenced a wide range of contemporary artists. His formative influence was undoubtedly Caravaggio, whose work he studied intensely in Rome. He was part of the broader Caravaggisti movement, alongside artists like the Dutch painters Gerrit van Honthorst and Hendrik ter Brugghen, and the Italian Bartolomeo Manfredi.

In Naples, his main artistic milieu, he was initially associated with painters like Battistello Caracciolo, another early Neapolitan follower of Caravaggio. His father-in-law, Giovanni Bernardo Azzolino, was also part of the local scene. He became the dominant figure, overshadowing many contemporaries. His success sometimes led to rivalries. There are accounts, possibly exaggerated, of a "Cabal of Naples," supposedly led by Ribera, Caracciolo, and Belisario Corenzio, aimed at excluding or harassing rival artists from other cities (like Domenichino, Guido Reni, and Annibale Carracci's followers) who sought major commissions in Naples. While the extent and nature of this "Cabal" are debated by historians, it points to the competitive atmosphere of the Neapolitan art world.

His fame attracted artists from elsewhere. Northern painters like the Fleming Hendrick van Somer and the Dutchman Matthias Stom worked in Naples and clearly absorbed Ribera's influence. He likely had contact with or knowledge of other major Italian Baroque figures like Guercino and potentially Anthony van Dyck during the latter's Italian travels. His students, particularly Luca Giordano, became major figures in their own right. Later Neapolitan masters like Mattia Preti and Francesco Solimena built upon the foundations laid by Ribera. His prints ensured his work was known to artists like Rembrandt in the Netherlands. This network of influence, interaction, and rivalry places Ribera firmly at the centre of the dynamic European art scene of the 17th century.

Personality and Anecdotes

While historical records primarily document Ribera's professional success, contemporary accounts and anecdotes offer glimpses of a complex and forceful personality. The nickname "Lo Spagnoletto" itself suggests a strong, perhaps even assertive, foreign identity within the Italian art world. He consistently signed his works as Spanish, often including "Jusepe de Ribera, español" or "Xàtiva" after his name, indicating pride in his origins despite spending his adult life in Italy.

Stories surrounding the "Cabal of Naples," whether entirely accurate or embellished by rivals, paint a picture of a fiercely competitive artist determined to protect his dominant position. These accounts allege that Ribera and his associates used intimidation and intrigue to monopolize major commissions, driving away talented outsiders. While perhaps exaggerated, these tales reflect the high stakes and intense rivalries within the lucrative Neapolitan art market.

Contrasting with this potentially ruthless professional ambition are indications of deep religious conviction, evident in the sincerity and power of his sacred art. Yet, his fascination with physical suffering, decay, and the grotesque aspects of humanity – seen in his depictions of martyrdoms, aged bodies, and peculiar figures – reveals a complex, perhaps contradictory, artistic temperament. He seemed drawn to the extremes of human experience, from profound piety to intense agony. One anecdote claims he refused an invitation from the King of Spain to return to his homeland, preferring to remain in Naples, suggesting a strong attachment to his adopted city and perhaps a certain independence of spirit. Overall, Ribera emerges as a figure of immense talent, strong will, and complex character, perfectly embodying the dramatic intensity of the Baroque era.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Jusepe de Ribera's legacy is substantial and multifaceted. He stands as one of the most important painters of the Spanish Golden Age, despite creating his major works on Italian soil. He served as a crucial bridge between the Italian and Spanish Baroque traditions, masterfully blending Caravaggio's dramatic naturalism with a Spanish intensity of feeling and realism. In Naples, he was the undisputed leader of the Neapolitan School of painting for decades, shaping its character and influencing generations of artists.

His powerful style, disseminated through his paintings and widely circulated etchings, had a significant impact across Europe. Artists in Spain, Italy, France, and the Netherlands were indebted to his dramatic compositions, his realistic portrayal of figures, and his masterful handling of light and shadow. His influence is visible in the works of Spanish masters like Velázquez and Murillo, and his prints were studied by Rembrandt.

After a period of relative neglect following the Baroque era, Ribera's work was rediscovered and celebrated by artists and writers in the 19th century, particularly during the Romantic period, who admired his dramatic intensity and emotional depth. Lord Byron, for instance, famously mentioned him as an exemplar of powerful, realistic art. Twentieth-century art history solidified his position as a major master of the Baroque, recognizing his technical brilliance, his psychological insight, and his unique contribution to European painting. He remains renowned for his unflinching depictions of human suffering and spiritual ecstasy, rendered with unparalleled technical skill and emotional force.

Conclusion: An Enduring Baroque Master

Jusepe de Ribera, "Lo Spagnoletto," remains a pivotal figure in 17th-century European art. His journey from Valencia to Rome and finally to Naples placed him at the crossroads of major artistic currents. By forging a unique style that combined the revolutionary tenebrism of Caravaggio with Spanish traditions of realism and emotional intensity, he dominated the Neapolitan art scene and created a body of work characterized by its dramatic power, psychological depth, and visceral physicality. As a painter, draftsman, and etcher, his technical mastery was exceptional. His depictions of saints, martyrs, philosophers, and ordinary folk continue to compel viewers with their unflinching honesty and profound humanity. Ribera's art transcends geographical boundaries, embodying the passionate spirit of the Baroque and leaving an indelible mark on the history of Western art.