Luca Cambiaso stands as one of the most significant and prolific artists of the 16th century Genoese School. Born in Moneglia, within the Republic of Genoa, on November 18, 1527, and active until his death in Madrid on September 6, 1585, Cambiaso's career bridged the gap between late Mannerism and the emerging Baroque. He was a highly sought-after painter of frescoes and altarpieces, renowned for his distinctive, geometrically simplified figure style and his pioneering use of dramatic nocturnal lighting effects. His influence extended beyond Genoa, notably reaching the Spanish court, and his innovations left a lasting mark on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Cambiaso's artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, Giovanni Cambiaso (1495–1579), himself a painter of some local repute. Giovanni recognized his son's prodigious talent early on and subjected him to a rigorous, almost militaristic training regimen, determined to forge him into a great artist. This intense early training involved constant drawing and the study of anatomy, often using geometric shapes to understand and depict the human form – a method that would profoundly shape Luca's mature style. Father and son collaborated on several early commissions in and around Genoa, providing Luca with invaluable practical experience.

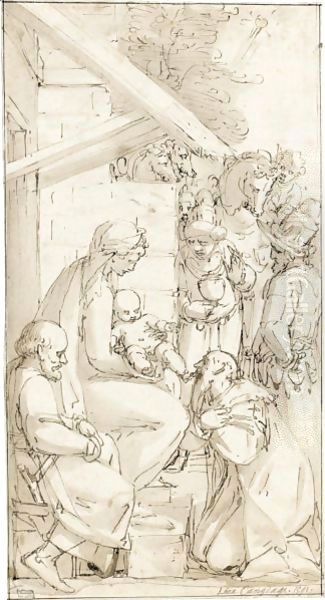

Beyond his father's direct instruction, the young Cambiaso absorbed influences from a variety of major Italian artists. He deeply admired the power and anatomical mastery of Michelangelo, whose work he likely studied through prints and drawings. The soft sfumato and gentle luminosity of Correggio also left a significant impression, particularly evident in Cambiaso's later handling of light and religious sentiment, as seen in works like the Adoration of the Shepherds.

Crucially, Cambiaso studied the works of artists active in Genoa itself. Perino del Vaga, a pupil of Raphael who brought Roman High Renaissance Mannerism to Genoa, was a key figure whose elegant compositions and fresco techniques Cambiaso analyzed closely, particularly Perino's decorations in the Palazzo Doria. He also looked towards the dynamic energy and dramatic compositions found in the frescoes of Pordenone and the distinctive Mannerist style of the Sienese painter Domenico Beccafumi. This eclectic mix of influences provided Cambiaso with a rich artistic vocabulary upon which to build his own unique vision. An early work like the Madonna and Child, now housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, likely reflects these formative stages.

Forging a Distinctive Genoese Manner

By the 1550s and 1560s, Luca Cambiaso had established himself as a leading independent master in Genoa, developing a highly personal and recognizable style. His most striking innovation was the radical simplification and geometrization of the human form. He often reduced figures to arrangements of blocky, cubic, or cylindrical shapes, creating compositions that possessed a powerful structure and clarity, even when depicting complex narratives or dynamic action. This "cubic" style, while perhaps influenced by his father's teaching methods, became a hallmark of Cambiaso's approach, allowing him to organize large-scale compositions efficiently and imbue them with a sense of monumental energy.

This distinctive approach is vividly demonstrated in numerous large-scale fresco cycles commissioned by Genoa's wealthy patrician families, such as the Doria and Grimaldi, for their palaces and churches. Works like the Martyrdom of St. George, created for the church of San Giorgio in Genoa, showcase this tendency towards geometric simplification within a dramatic narrative context. Similarly, frescoes such as the dynamic Rape of the Sabines (mid-1560s) and the powerful Odysseus Slays the Suitors in the Palazzo Grimaldi della Meridiana exemplify his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with clarity and force, using this simplified formal language.

Cambiaso was exceptionally prolific, known for his speed and efficiency, particularly in fresco painting. This rapid execution was underpinned by his constant practice of drawing. He produced thousands of preparatory sketches, often rapidly executed in pen and wash, where he worked out compositional ideas and explored figure poses using his characteristic geometric shorthand. These drawings were not merely preparatory tools but possess an artistic vitality of their own, revealing his thought process and his mastery of form and movement.

Pioneering Nocturnes and Chiaroscuro

Alongside his geometric style, Luca Cambiaso made significant contributions to the depiction of light, particularly in his development of nocturnal scenes, or nocturnes. He was among the very first Italian artists to consistently explore the dramatic possibilities of artificial light sources, most notably candlelight, within his paintings. This involved a sophisticated use of chiaroscuro – the strong contrast between light and shadow – to model forms, create atmosphere, and heighten emotional intensity.

His Madonna of the Candle, a notable work likely inspired by Correggio's famous Nativity (also known as La Notte), exemplifies this interest. The single candle becomes the focal point, casting a warm, intimate glow on the central figures while plunging the surrounding areas into deep shadow. This creates a sense of mystery and focuses the viewer's attention on the sacred subject. Similarly, his Adoration of the Shepherds from 1570 uses the humble light source associated with the Nativity story to create a scene of profound tenderness and spiritual significance, rendered with dramatic light effects.

This innovative use of light and shadow was highly influential. It moved beyond the more evenly lit compositions typical of the High Renaissance and anticipated the dramatic lighting that would become a defining characteristic of Baroque painting in the following century. Artists like Caravaggio and Georges de La Tour, famed for their mastery of tenebrism and candlelit scenes, owe a debt to Cambiaso's pioneering explorations in this area. His nocturnes demonstrated how light itself could become a primary expressive element in painting.

Collaboration and Artistic Milieu in Genoa

Genoa in the mid-16th century possessed a vibrant artistic environment, and Cambiaso actively participated in it, often collaborating with other prominent artists. His most frequent collaborator during the 1550s and 1560s was Giovanni Battista Castello, known as "Il Bergamasco". Castello, an accomplished painter and architect originally from Bergamo, worked closely with Cambiaso on several major decorative projects. Their partnership is evident in the decoration of the piano nobile (main floor) of Luca Giustiniani's villa in Albaro.

A particularly significant collaboration took place at the church of the Santissima Annunziata di Portoria in Genoa. Here, Castello painted the ceiling fresco depicting the Savior Judging the World, while Cambiaso executed the large frescoes on the side walls, representing the Fate of the Blessed and The Damned. These projects demonstrate a synergy between the two artists, with Castello's architectural sense perhaps complementing Cambiaso's powerful figure painting. Castello's style, particularly in decorative elements and architectural framing, likely influenced Cambiaso's approach to integrating his frescoes within larger decorative schemes.

While Cambiaso had studied Perino del Vaga's work intently in his youth, their relationship seems to have been one of influence rather than direct collaboration or intense rivalry. Cambiaso absorbed lessons from Perino's sophisticated Mannerism but ultimately forged his own, more robust and geometrically inclined path. Any "competition" would likely have been implicit, stemming from their differing styles and prominence within the Genoese art market. Similarly, his study of Pordenone and Beccafumi reflects an engagement with contemporary trends rather than documented personal interaction or rivalry. His association with figures like Giovan Battista Alessi, a lawyer and theorist, points to his integration within the broader cultural and intellectual life of Genoa, beyond purely artistic circles.

Personal Trials and Spanish Summons

Despite his professional success, Cambiaso's personal life was marked by significant emotional hardship. The death of his beloved wife left him grief-stricken. His subsequent desire to marry his deceased wife's sister, a practice requiring papal dispensation, was ultimately denied by the Church authorities. According to contemporary biographers like Raffaele Soprani, this refusal plunged Cambiaso into a deep melancholy that affected him for the rest of his life. Adding to his troubles were disputes concerning his late wife's property and inheritance, entangling him in legal difficulties.

However, Cambiaso's artistic reputation continued to grow, extending far beyond Genoa. His fame reached the ears of one of the most powerful patrons in Europe: King Philip II of Spain. The king was overseeing the massive construction and decoration of the Royal Monastery-Palace of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, near Madrid. Impressed by Cambiaso's skill, particularly in large-scale fresco, Philip II summoned the Genoese artist to the Spanish court in 1583. This prestigious invitation represented a pinnacle of recognition for Cambiaso.

The Escorial and Final Years

Arriving in Spain, Cambiaso was immediately put to work on the vast decorative program at El Escorial. He was tasked with painting numerous frescoes and altarpieces for the basilica and other parts of the complex, working alongside other prominent Italian and Spanish artists like Federico Zuccaro and Pellegrino Tibaldi. Although his time in Spain was relatively short, he executed significant works, contributing to the austere grandeur desired by Philip II for his monumental project. His contributions included scenes for the main altarpiece and frescoes in the choir and sacristy, continuing to employ his characteristic style but perhaps adapting slightly to the more sober religious atmosphere of the Spanish court.

In recognition of his service and talent, Philip II appointed Cambiaso as a court painter. However, the artist's time in Spain was tragically brief. Whether due to the lingering effects of his personal sorrows, the pressures of the demanding Escorial project, or declining health, Luca Cambiaso died at El Escorial on September 6, 1585, only two years after his arrival. Anecdotes suggest that his melancholy persisted, and some accounts claim he died leaving his final commissioned work unfinished, overwhelmed by sadness or illness.

Drawing as a Foundation

Throughout his career, drawing remained fundamental to Cambiaso's artistic practice. He was an incredibly prolific draftsman, and thousands of his drawings survive today, housed in major collections worldwide. These drawings, typically executed in pen and brown ink with brown wash over preliminary sketches in chalk or graphite, are remarkable for their energy, fluidity, and the consistent application of his geometric method for constructing figures. Even in rapid sketches, the underlying structure of cubes, ovals, and cylinders is often apparent.

These drawings served multiple purposes: exploring initial ideas, working out complex compositions, studying individual poses, and providing models for workshop assistants. Works like the drawing The Entombment of Christ (Nivaagaard Collection) showcase his ability to convey deep emotion and complex arrangements through line and wash. Beyond their preparatory function, Cambiaso's drawings were admired as artworks in their own right and were eagerly collected even during his lifetime. They provide invaluable insight into his creative process and served as teaching tools, influencing generations of artists who studied their bold simplification and dynamic energy.

Legacy and Influence

Luca Cambiaso's impact on the course of art history was significant, particularly within Genoa and Spain, and through his influence on the development of Baroque painting. His most immediate legacy was on the Genoese School. He trained several pupils who carried on his style, including his son Orazio Cambiaso, Lazzaro Tavarone (who accompanied him to Spain and completed some of his unfinished work at El Escorial), Giovanni Andrea Ansaldo, and Simone Barabino. Through them, his approach to composition and figure painting continued to shape Genoese art into the early 17th century.

His pioneering use of chiaroscuro and nocturnes had a broader impact. While direct influence is sometimes hard to trace definitively, his work prefigures the dramatic lighting strategies employed by Caravaggio and his followers (the Caravaggisti), as well as other Baroque masters of light like Georges de La Tour in France and potentially impacting artists in the circle of Rembrandt in the Netherlands. Cambiaso demonstrated how stark contrasts of light and shadow could create powerful psychological and spiritual effects.

His distinctive geometric simplification of form, while perhaps less directly imitated, represents a fascinating early exploration of abstracting the human figure for expressive and structural purposes. While not a direct precursor to 20th-century Cubism, his method highlights a recurring tendency in art to seek underlying geometric structures within natural forms. His allegorical works, such as the Vanity of Earthly Love, also show his engagement with the intellectual and moral themes prevalent in Mannerist art.

Conclusion

Luca Cambiaso remains a pivotal figure in 16th-century Italian art. As the dominant force in the Genoese School for much of his career, he developed a unique and powerful artistic language characterized by bold geometric simplification and innovative explorations of light and shadow. His prolific output across painting, fresco, and drawing, combined with his ability to manage large-scale commissions efficiently, made him highly sought after by patrons in both Italy and Spain. Despite personal tragedies, his artistic vision remained strong, influencing his contemporaries and paving the way for key developments in Baroque art. Cambiaso's work embodies a compelling blend of Mannerist complexity, formal rigor, and an emerging Baroque dynamism and emotional intensity, securing his place as a significant innovator in the transition between two major artistic eras.