André Sureda (1872-1930) stands as a notable figure among the French Orientalist painters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Versailles, his artistic journey led him from the esteemed academies of Paris to the sun-drenched landscapes and vibrant cultures of North Africa. His work, characterized by a sensitive portrayal of light, color, and the human element of the Maghreb, offers a distinct perspective within the broader Orientalist tradition. This exploration delves into Sureda's life, his artistic development, his key works, and his place within the rich tapestry of art history, particularly in relation to his contemporaries and the enduring allure of the East for Western artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

André Sureda was born in Versailles, France, in 1872, into a period of significant artistic ferment. His formal artistic education commenced at the prestigious École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the traditional bastion of academic art in France. There, he studied under the tutelage of respected masters such as Tony Robert-Fleury and Jules Joseph Lefebvre. Both Robert-Fleury, known for his historical scenes and portraits, and Lefebvre, celebrated for his female nudes and allegorical figures, were influential figures in the academic art world of their time. They imparted a rigorous training grounded in drawing, composition, and the classical tradition.

However, Sureda's temperament and artistic aspirations soon led him to seek a path beyond the strictures of the academic studio. The provided information indicates he "quickly" left the workshops of his mentors, desiring "more free artistic space." This decision, made around 1894 when he began to focus intently on his painting career, suggests an early inclination towards personal expression and perhaps a burgeoning interest in subjects and styles that lay outside the conventional academic repertoire. This quest for artistic independence would become a defining characteristic of his career, ultimately leading him far from the salons of Paris.

The Call of the Maghreb: Journeys and Inspirations

The allure of North Africa, often termed "the Orient" by Europeans of the era, exerted a powerful pull on many artists, and André Sureda was no exception. His travels to this region, particularly to Algeria and Morocco, became the cornerstone of his artistic identity. These journeys provided him with a wealth of new subjects, a different quality of light, and an immersion in cultures that were perceived as exotic and captivating by many Westerners. The exact timeline of his initial and subsequent travels is a subject for detailed biographical research, but it is clear that these experiences profoundly shaped his oeuvre.

The landscapes, bustling city scenes, intimate domestic interiors, and portraits of the local populace became his primary focus. Unlike some Orientalist painters who relied on studio props and imagined scenes, Sureda's work often conveys a sense of direct observation and engagement with his surroundings. His move to Algeria, as mentioned in some accounts, would have facilitated a deeper, more sustained interaction with the local environment and its people, allowing for a more nuanced portrayal than that of a fleeting visitor. This immersion is crucial for understanding the authenticity that many find in his depictions.

Artistic Style: Realism, Romanticism, and the Play of Light

André Sureda's artistic style can be seen as a fusion of Realist observation with a Romantic sensibility, all filtered through the unique visual stimuli of North Africa. He demonstrated a keen eye for detail, capturing the textures of fabrics, the specifics of architectural elements, and the individual characteristics of his sitters. His academic training would have provided him with the technical skills necessary for such precise rendering.

However, his work transcends mere topographical accuracy. There is often an evocative quality, a sense of atmosphere, and an appreciation for the human drama, however subtle, within his scenes. His use of color was vital in conveying the intense light of the Maghreb. He skillfully managed vibrant hues and the interplay of light and shadow to create depth and mood. Whether depicting a sun-drenched marketplace or the cool interior of a home, light is often a key protagonist in his compositions. His brushwork, while capable of fine detail, could also be expressive, lending vitality to his figures and settings. This blend allowed him to capture both the tangible reality and the perceived mystique of the lands he painted.

Representative Works: Glimpses into Sureda's World

Several works are cited as representative of André Sureda's artistic output, each offering insight into his thematic concerns and stylistic approaches.

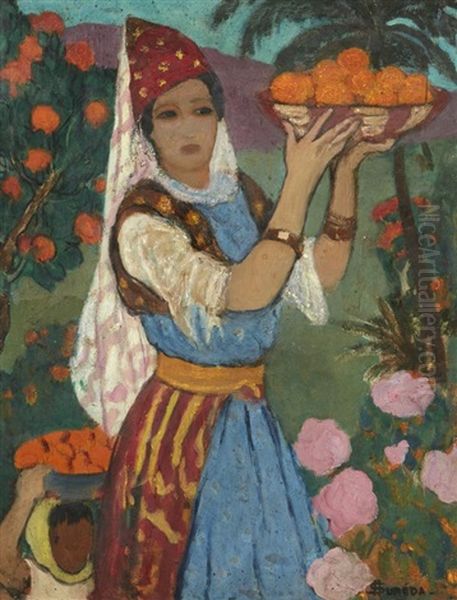

_Femme aux Oranges_ (Woman with Oranges, 1919): This title suggests a portrait or genre scene, likely featuring a local woman, with oranges perhaps symbolizing the fertility or produce of the region. The date places it in his mature period. Such a work would allow for an exploration of costume, physiognomy, and the use of still life elements to enhance the composition and narrative.

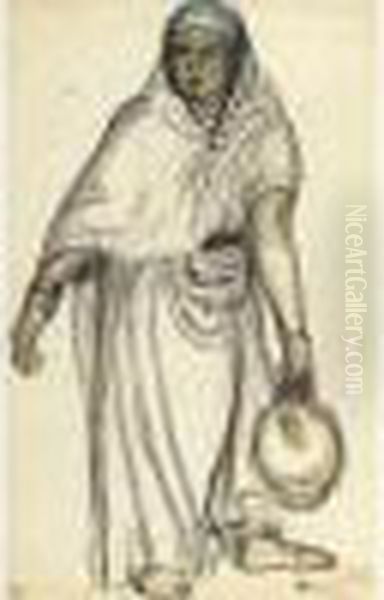

_Jeune fille à la cruche_ (Young Girl with a Pitcher): This is a classic Orientalist theme, often depicting daily life and the roles within it. The pitcher could signify a task like fetching water, providing a glimpse into the everyday routines of the local people. It offers an opportunity for the artist to portray youthful innocence and traditional attire.

_Les Deux Amies_ (The Two Friends): This title implies an intimate scene, perhaps set within a domestic interior, focusing on the relationship between two women. Such subjects allowed artists to explore themes of companionship and the private lives of women in North African societies, which were often inaccessible to male Western artists and thus a subject of much fascination and speculation.

_Child with an Orange_: Similar to _Femme aux Oranges_, this piece likely focuses on a youthful subject, with the orange again serving as a significant visual or symbolic element. Children were frequent subjects for Orientalist painters, often depicted with a sense of charm or exoticism.

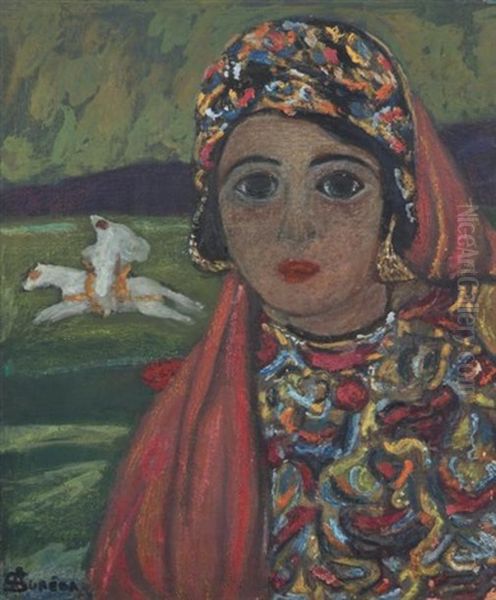

_Young Kabyle Girl with Black Eyes_: The specificity of "Kabyle" points to Sureda's engagement with particular ethnic groups within Algeria. The Kabyle people, primarily from the mountainous regions of northern Algeria, have a distinct cultural heritage. This title suggests a portrait focused on capturing the distinct features and perhaps the spirit of a young individual from this community.

_Scène de Hammam_ (Hammam Scene): The hammam, or public bath, was a subject of immense interest to Orientalist painters, offering a rare (though often imagined or heavily stylized) glimpse into a private, sensual world. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres famously depicted such scenes, though Ingres's were largely fantastical. Sureda's take would be interesting to compare, to see if it leaned more towards observed reality or romanticized convention.

_Jeune Femme Dansant_ (Young Woman Dancing): Dance was another popular theme, embodying the perceived exoticism and sensuality of the Orient. Such a work would allow Sureda to explore movement, costume, and the cultural expressions of the region. The auction price of 1,200 Euros for a work of this title indicates a level of market recognition for his art.

_Jeune Femme et Enfant_ (Young Woman and Child): This theme of maternity or caregiving is universal, but in an Orientalist context, it would also be imbued with the specific cultural details of North Africa, from attire to setting.

These titles collectively paint a picture of an artist deeply engaged with the human and cultural landscape of North Africa, focusing on portraits, genre scenes, and the depiction of everyday life, often with a particular emphasis on women and children.

Sureda in the Context of Orientalism

To fully appreciate André Sureda's contribution, it is essential to place him within the broader context of the Orientalist art movement. Orientalism, as a phenomenon in Western art, literature, and scholarship, emerged in the late 18th century and flourished throughout the 19th century, continuing into the early 20th. It was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, and a romantic fascination with the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Pioneering figures like Eugène Delacroix, whose visit to Morocco and Algeria in 1832 revolutionized French painting with its vibrant color and dynamic compositions, set a powerful precedent. Delacroix’s sketches and paintings, such as _Women of Algiers in their Apartment_, had a profound impact on subsequent generations.

Later in the 19th century, artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme became immensely popular for their highly detailed, almost photographic depictions of Oriental scenes, though often criticized later for perpetuating stereotypes. Gérôme's works, such as _The Snake Charmer_ or _Prayer on the Rooftops_, defined a certain academic Orientalism. Other notable figures include Théodore Chassériau, who blended a Neoclassical sensibility with Romantic exoticism in his depictions of Algerian life, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose odalisques and bath scenes, like _La Grande Odalisque_ and _The Turkish Bath_, though often based more on fantasy than direct observation, were hugely influential in shaping the Western image of the Oriental woman.

By the time Sureda was active, Orientalism had evolved. While the initial romantic allure persisted, some artists sought a more ethnographic or personal engagement. Alphonse-Étienne Dinet (who later converted to Islam and took the name Nasr’Eddine Dinet) spent much of his life in Algeria and is known for his sympathetic and deeply informed portrayals of Algerian life, often collaborating with Sliman Ben Ibrahim. American artists like Frederick Arthur Bridgman also made significant contributions, spending considerable time in North Africa and producing works noted for their archaeological accuracy and brilliant light. Austro-French painters like Ludwig Deutsch and Rudolf Ernst were known for their meticulous, jewel-like paintings of everyday scenes, scholars, and guards, often characterized by an intense focus on detail and texture.

Earlier French artists like Gustave Guillaumet also left a significant mark with their depictions of the harsh beauty of the Algerian landscape and the dignity of its people, often focusing on themes of daily struggle and resilience. Sureda’s work seems to align with a strand of Orientalism that, while still framed by a Western perspective, sought to capture the character and atmosphere of North Africa with a degree of sensitivity and directness. His focus on individual portraits and scenes of daily life suggests an interest in the human dimension beyond mere exotic spectacle.

Contemporaries in the Broader French Art Scene

While Sureda specialized in Orientalist themes, it's also useful to consider the broader French art scene during his active years (roughly 1894-1930). This period witnessed the legacy of Impressionism, the rise of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism. While Sureda's style remained largely representational, the artistic environment in Paris was one of radical experimentation.

Artists like Henri Matisse, a contemporary, was also profoundly influenced by North African art and culture, particularly after his visits to Morocco in 1912-1913. Matisse's response, however, was to integrate these influences into his modernist exploration of color, line, and decorative pattern, as seen in works like _The Moroccan Café_. Georges Rouault, another contemporary who, like Matisse, studied under Gustave Moreau (a teacher at the Beaux-Arts contemporary with Robert-Fleury and Lefebvre), pursued a deeply personal and expressive figurative style, though his themes were primarily religious and social.

The fact that Sureda chose to leave the academic fold of Robert-Fleury and Lefebvre suggests a desire for a more personal artistic language. While he did not embrace the avant-garde movements to the extent of a Matisse, his path as an Orientalist allowed him a form of independence and a specialized niche that was distinct from both strict academicism and radical modernism. His work can be seen as part of a continuing tradition of French figurative painting that found rich new subject matter in foreign lands.

Other artists who traveled and depicted non-European cultures, though perhaps not strictly "Orientalists" in the North African sense, also formed part of this global artistic exploration. For instance, the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt traveled extensively in the Middle East for his religious paintings, seeking authenticity in landscape and custom. The British painter John Frederick Lewis lived for many years in Cairo and produced incredibly detailed watercolors and oil paintings of Egyptian life. These broader trends highlight the global reach of artists during this period.

Exhibitions and Later Recognition

The mention of André Sureda's works being exhibited in recent times, such as at the Daegu Museum of Art in South Korea (2023) and the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art in Japan (2024), indicates a continuing interest in his art and, by extension, in the Orientalist genre. Such exhibitions play a crucial role in re-evaluating artists and bringing their work to new audiences. The inclusion of his art in these international venues suggests that his depictions of North African life possess a quality that resonates beyond their original historical and cultural context.

The art market also provides a measure of an artist's standing, and the sale of works like _Jeune Femme Danseant_ at auction demonstrates that there is a collector base for Sureda's paintings. The value of Orientalist art, in general, has seen periods of significant interest, driven by both aesthetic appreciation and historical curiosity.

Historical Position and Legacy

André Sureda's historical position is primarily that of a dedicated and skilled Orientalist painter who contributed to the rich and complex visual record of Western encounters with North Africa. He operated within a tradition established by giants like Delacroix and Gérôme but found his own voice in the sensitive portrayal of the people and environments he encountered. His decision to pursue "more free artistic space" early in his career set him on a path that, while perhaps not radically innovative in terms of style compared to the burgeoning modernist movements, was nonetheless a personal and focused artistic journey.

His work serves as a valuable document of a particular time and perspective. Like all Orientalist art, it is viewed today through a lens that acknowledges the colonial context and the power dynamics inherent in Western depictions of non-Western cultures. However, within this framework, Sureda's paintings often seem to strive for a degree of empathy and directness in their portrayal of individuals and daily life. His commitment to his chosen subject matter, evident in his travels and the body of work he produced, marks him as a significant practitioner within the later phase of the Orientalist movement.

The art world's continued engagement with his work, through exhibitions and the art market, suggests that André Sureda's contributions are still valued. He may not be as widely known as some of the leading names of Orientalism or the major figures of modern art, but his paintings offer a compelling and nuanced window onto the landscapes and cultures of North Africa as seen through the eyes of a talented French artist at the turn of the twentieth century. His legacy lies in these evocative images, which continue to speak of a fascination with light, color, and the human experience in a world far from his native Versailles.

In conclusion, André Sureda carved out a distinctive niche for himself. He absorbed the rigorous training of the École des Beaux-Arts under masters like Tony Robert-Fleury and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, but his artistic spirit yearned for the vivid realities of North Africa. His paintings, from the intimate _Jeune fille à la cruche_ to the culturally specific _Young Kabyle Girl with Black Eyes_, reflect a dedicated engagement with his subjects. While working in a period of explosive modernist innovation championed by figures like Matisse, Sureda remained committed to a representational style enriched by the unique atmosphere of the Maghreb, contributing his personal vision to the diverse and enduring legacy of Orientalist art.