Introduction to the Artist

Louis Auguste Girardot stands as a notable figure within the French Orientalist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in France in 1856, he dedicated much of his artistic career to capturing the landscapes, people, and daily life of North Africa, particularly Morocco. His work reflects the deep fascination that many European artists of his era held for the cultures and aesthetics perceived as 'exotic' and distinct from their own. Girardot's paintings serve as visual documents, filtered through a European lens, of a world that was undergoing significant change yet retained a powerful allure for the Western imagination. He was an artist whose canvases transported viewers to sun-drenched terraces and bustling marketplaces, contributing to the rich tapestry of Orientalist art. His lifespan, stretching from the mid-19th century well into the 20th (he passed away in 1933), placed him at a fascinating intersection of artistic traditions and emerging modern sensibilities.

Early Life and French Roots

Louis Auguste Girardot entered the world in 1856 in Châtelneuf, a location within France sometimes referred to, perhaps poetically, as "Little Scotland." This places his formative years firmly within the Second French Empire and the subsequent Third Republic, periods of significant social and artistic transformation in France. While the specific details of his artistic training are not fully illuminated by the readily available records referenced, it was customary for aspiring artists of his generation to seek formal education. This often involved study at prestigious institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris or apprenticeship under established masters. The artistic environment he grew up in was vibrant and complex; Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet, had challenged academic norms, while Impressionism, with figures such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, was radically redefining the perception of light and contemporary life. Simultaneously, the official Salon system, though evolving, still heavily favored academic painting, including historical and mythological scenes, as well as the increasingly popular Orientalist genre. It was within this dynamic milieu that Girardot would have begun to shape his artistic identity.

The Rise of Orientalism

The nineteenth century witnessed an explosion of European interest in the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, a phenomenon broadly termed Orientalism. This fascination was fueled by various factors, including colonial expansion (particularly France's involvement in Algeria and later Morocco and Tunisia), increased travel opportunities, archaeological discoveries, and romantic literature. Artists played a crucial role in shaping and disseminating Western perceptions of the 'Orient'. They traveled to these regions, sketching and painting scenes that ranged from intimate domestic interiors and portraits to grand historical reconstructions and bustling street scenes. Early pioneers like Eugène Delacroix, whose trip to Morocco in 1832 proved profoundly influential, captured the vibrant color and dynamic energy he encountered. Later, artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme became immensely popular for their highly detailed, almost photographic depictions of Middle Eastern life, though often criticized today for perpetuating stereotypes. Others, like Eugène Fromentin, combined painting with writing, offering evocative accounts of their travels in North Africa. This established tradition provided a rich context for artists like Girardot, offering both inspiration and a receptive market for their work.

Girardot's Engagement with Morocco

Girardot's artistic output clearly indicates a deep and sustained engagement with Morocco. His choice of subjects frequently revolved around Moroccan themes, suggesting either extended stays in the country or a profound inspiration drawn from its culture. The North African landscape, the distinctive architecture, the vibrant textiles, and the daily routines of its inhabitants offered a wealth of visual material that contrasted sharply with metropolitan France. Tangier, in particular, was a popular destination for international artists and writers during this period, known for its unique position and cosmopolitan atmosphere, which likely attracted Girardot. His works aimed to capture the specific quality of light, the textures of fabrics and buildings, and the physiognomy and postures of the local people. Like many Orientalist painters, he likely sought authenticity in details of dress and setting, contributing to the ethnographic dimension, however interpreted, of his art. The source materials even hint at an interest extending to local crafts, mentioning a connection to the patterns found in traditional Moroccan Kaftan embroidery, suggesting a potentially deeper observation of the culture beyond surface appearances.

Key Works: Windows into North Africa

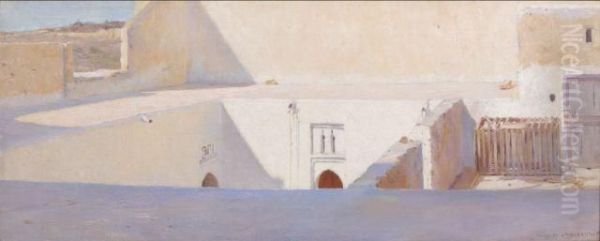

Several specific paintings provide insight into Girardot's artistic focus and style. Terrasse à Tanger (Terrace in Tangier), dated 1887, is an oil painting measuring 33 x 80 cm. The title itself evokes a common Orientalist motif – the terrace as a liminal space, offering both privacy and a vantage point onto the world outside. It suggests a scene bathed in the characteristic North African light, perhaps depicting figures relaxing or gazing out over the city or sea. Its relatively early date in his documented oeuvre indicates his commitment to Moroccan subjects from at least his early thirties. Another significant work is A Moroccan In Repose, painted in 1892. This title points towards a portrait or genre scene focused on a single figure, capturing a moment of quietude. Such depictions could range from sensitive character studies to more generalized 'types', reflecting the complex interplay between observation and artistic convention inherent in Orientalism. A later work, La Fuite en Égypte (The Flight into Egypt), dated around 1905 and notably larger at 183 x 340 cm, takes a traditional biblical subject and likely transposes it into a North African setting. This practice was not uncommon; artists like Luc-Olivier Merson also famously depicted biblical scenes within meticulously rendered Middle Eastern landscapes, blending religious narrative with Orientalist aesthetics. This work suggests Girardot tackled larger, perhaps more ambitious compositions later in his career, integrating his regional focus with established Western themes.

Artistic Style and Approach

Girardot worked within the broad stylistic framework of Orientalism, which, while diverse, often shared certain characteristics. Based on his known works and the general trends of the period, his style likely involved careful draughtsmanship and a commitment to representational accuracy, hallmarks of the academic training many artists of his time received. A key element would undoubtedly be the treatment of light and color. Orientalist painters were often captivated by the intense sunlight of North Africa and sought to convey its effects on landscapes, architecture, and figures, often employing a brighter palette than was typical for scenes set in Europe. Detail was frequently emphasized, particularly in rendering the textures of fabrics, the intricacies of architectural decoration, and the specific features of individuals or ethnic 'types'. While some Orientalists leaned towards dramatic historical or narrative scenes, Girardot's known titles suggest a focus on genre scenes, portraiture, and landscapes – capturing moments of daily life, quiet contemplation, or scenic views. His approach likely balanced direct observation with studio composition, a common practice where sketches made on location were later developed into finished oil paintings. The overall effect aimed for was often one of evocative realism, transporting the viewer to a distant, alluring world.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Landscape

Louis Auguste Girardot practiced his art during a period of immense artistic diversity in France and Europe. While he focused on Orientalism, the art world around him was constantly evolving. The Impressionists, including Camille Pissarro and Berthe Morisot, had already revolutionized painting, and their influence continued to be felt. Following them came the Post-Impressionists, such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, who pushed artistic boundaries in highly individual directions – Gauguin himself famously sought inspiration in non-Western cultures, albeit in the South Pacific rather than North Africa. Symbolism, with artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, explored themes of myth, dream, and the psyche, often employing rich color and imaginative compositions. Within Orientalism itself, Girardot had numerous contemporaries. Étienne Dinet (later Nasr'Eddine Dinet after converting to Islam) was renowned for his vibrant and sympathetic portrayals of Algerian life. Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant achieved great fame for his large-scale, dramatic scenes often set in Morocco. Gustave Guillaumet offered sensitive depictions of the harsh beauty of the Algerian landscape and its inhabitants. Georges Clairin, a friend of the actress Sarah Bernhardt, also painted Moroccan scenes. Girardot's participation in a European Masters print exhibition in 1898 further indicates his connection to the broader art market and potentially an interest in graphic arts alongside painting. He was thus part of a specific tradition but operated within a much wider, dynamic artistic context.

Navigating Identity: The Girardot Name

It is worth noting that the name "Girardot" appears multiple times in French history and art, sometimes leading to potential confusion. The provided source materials themselves highlight instances where Louis Auguste Girardot the painter (1856-1933) might be conflated with others. For instance, there are references to a French military officer, Jean B. Girardot, active in the early 1700s in North America, entirely unrelated to the artist. More significantly, the source text seems to confuse the painter with a similarly named collector, Louis Auguste Girardot (1805-1883), attributing connections with artists like François-Alexandre Hazé, Émile Alfred Vivier de La Chaussée, Jules Dumoutet, and even the famed architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and painter Jean-Léon Gérôme to the painter, when these connections likely belong to the earlier collector. While Gérôme was a prominent Orientalist and could have influenced the painter Girardot, the specific collaborative relationships mentioned seem tied to the earlier namesake. Furthermore, the text mentions unrelated figures like Louis-Abel Girardot (a geologist) and even a brand of sparkling wine, highlighting the need for careful differentiation when researching the artist. The focus must remain on Louis Auguste Girardot, the French Orientalist painter born in 1856 and deceased in 1933.

Later Years and Legacy

Louis Auguste Girardot lived until 1933, witnessing the dramatic shifts in art that characterized the early twentieth century. Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, and various forms of abstraction came to dominate the avant-garde, pushing representational styles like Orientalism increasingly out of critical favor, although it retained a degree of popular appeal. Information regarding Girardot's later career and output is less detailed in the provided sources, but his La Fuite en Égypte (c. 1905) shows he was still producing significant work after the turn of the century. His death in 1933 marked the end of a long life dedicated to art, spanning from the heyday of academic Orientalism into the modern era. His legacy resides in his contributions to the Orientalist genre. His paintings, such as Terrasse à Tanger and A Moroccan In Repose, offer valuable examples of how French artists perceived and depicted North Africa during this period. While contemporary perspectives often critique Orientalism for its potential biases and romanticized or stereotyped portrayals, the works themselves remain historical documents and examples of skilled academic painting technique applied to specific, culturally resonant subject matter. Girardot's art provides a window into both the world he depicted and the European mindset that shaped those depictions.

Conclusion

Louis Auguste Girardot (1856-1933) was a dedicated French painter whose artistic journey led him deep into the visual landscapes and cultural milieu of North Africa, particularly Morocco. As an Orientalist, he participated in a major artistic movement of his time, contributing works like Terrasse à Tanger and A Moroccan In Repose that captured the allure of the region through a distinctly European lens. Working alongside contemporaries yet forging his own path, he navigated an art world undergoing profound changes. While overshadowed perhaps by the rise of Modernism and subject to the critical re-evaluation of Orientalism, Girardot's paintings remain testaments to his skill and his fascination with the vibrant world beyond Europe's borders. He remains a figure worthy of study within the context of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French art.