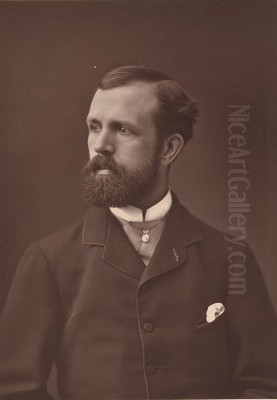

Frederick Arthur Bridgman stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American art, celebrated primarily for his captivating depictions of North African and Middle Eastern scenes. An expatriate who spent much of his prolific career in France, Bridgman skillfully blended the meticulous academic training he received with a growing sensitivity to light and color, earning him the moniker "the American Gérôme," yet establishing a distinct artistic identity that resonated on both sides of the Atlantic. His extensive travels provided a deep wellspring of inspiration, allowing him to portray the landscapes, architecture, and daily life of distant lands with remarkable detail and vibrant energy, securing his place as a leading Orientalist painter of his generation.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in America

Frederick Arthur Bridgman was born on November 10, 1847, in the small town of Tuskegee, Alabama. His father was a physician, and his mother hailed from New England, tracing her ancestry back to early Massachusetts settlers. The family's circumstances led them away from the South during Bridgman's early childhood. Following his father's death, the family relocated first to Boston and subsequently to New York City. It was in New York that the young Bridgman's artistic inclinations began to take shape professionally.

Seeking practical application for his drawing skills, Bridgman secured an apprenticeship as a draftsman and engraver at the American Bank Note Company from 1864 to 1865. This role, while commercial, undoubtedly honed his precision and attention to detail, skills that would serve him well in his future painting career. Concurrently, he pursued formal art education, taking evening classes. He studied diligently at the Brooklyn Art Association and later at the prestigious National Academy of Design, immersing himself in the foundational principles of drawing and painting within the American art scene of the time. These formative years provided him with essential training and exposure, laying the groundwork for his ambitious move abroad.

The Parisian Experience: Under Gérôme's Wing

Recognizing the limitations of American art training compared to the opportunities available in Europe, Bridgman made the pivotal decision to move to Paris in 1866. This move placed him at the epicenter of the Western art world. He sought out the tutelage of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most renowned and influential academic painters of the era, particularly famous for his own highly detailed Orientalist and historical subjects. Bridgman was accepted into Gérôme's demanding atelier at the École des Beaux-Arts, the official bastion of French academic art.

Under Gérôme's rigorous instruction, Bridgman spent four formative years mastering the principles of academic painting. Gérôme emphasized precise draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, a smooth, highly finished surface (fini), and meticulous research into historical and ethnographic details. Bridgman proved to be an adept and dedicated student, quickly absorbing his master's techniques and approach. He became one of Gérôme's most favored pupils, earning respect within the competitive environment of the atelier. The influence of Gérôme's style, particularly his choice of Middle Eastern themes and his polished execution, was profound and immediately apparent in Bridgman's early Parisian works.

Developing an Independent Style: Beyond the Master

While the comparison to his teacher earned him the nickname "the American Gérôme," Bridgman was not content to merely replicate his master's style. Even during his training and certainly in the years that followed, he began to cultivate a more personal artistic vision. While retaining the strong draftsmanship and compositional structure learned from Gérôme, Bridgman gradually moved away from the tight, almost photographic finish favored by his teacher. He started exploring a more naturalistic aesthetic.

This evolution involved a greater emphasis on the effects of light and atmosphere. Bridgman became increasingly interested in capturing the brilliant sunlight of North Africa, leading him to adopt a brighter, more luminous color palette than Gérôme typically employed. His brushwork also became looser and more visible, imbuing his canvases with a greater sense of immediacy and texture. This shift reflected broader trends in European art, including the influence of Realism and the burgeoning Impressionist movement, though Bridgman never fully embraced Impressionism's dissolution of form. His unique contribution lay in applying this more painterly, light-filled approach to Orientalist subjects, creating scenes that felt both exotic and vibrantly alive.

Journeys to the East: Inspiration and Observation

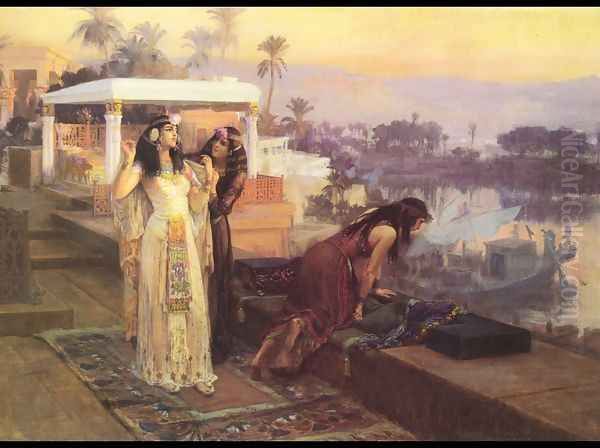

Bridgman's fascination with the "Orient"—primarily North Africa and the Middle East—became the defining passion of his career. His first major voyage took place between 1872 and 1874, during which he traveled extensively through Algeria and Egypt. This trip was transformative. He was captivated by the unfamiliar landscapes, the dazzling light, the intricate architecture, and the rhythms of daily life he encountered. Unlike some Orientalist painters who relied heavily on studio props and imagination, Bridgman immersed himself in direct observation.

During this initial journey, he produced an astonishing volume of work: approximately 300 sketches and studies drawn from life. These plein-air oil sketches, watercolors, and pencil drawings captured architectural details, street scenes, local costumes, and figures with remarkable freshness and accuracy. They became an invaluable resource, serving as the basis for many of his larger, more elaborate studio paintings created back in Paris over the following years. He meticulously documented what he saw, from the bustling markets of Algiers to the ancient ruins along the Nile.

Bridgman returned to North Africa multiple times throughout his career. He developed a particular affinity for Algeria, delving into the study of its traditional architecture and decorative arts, especially the intricate details of Moorish interiors. These elements frequently feature in his paintings, providing authentic settings for his genre scenes. His commitment to firsthand experience lent a palpable sense of authenticity to his work, distinguishing him from artists who depicted the East purely through a lens of romantic fantasy.

One anecdote highlights his method of gaining access to intimate settings. During the winter of 1885-86 in Algiers, he reportedly arranged through a guide to work within the home of a young widow named Baïa. This allowed him privileged access to observe the domestic lives of women, subjects often inaccessible to male European artists. This experience likely informed many of his sensitive portrayals of women in interior settings. His travels and observations were also compiled and shared in his book, Winters in Algeria, published in 1890 with his own illustrations, further cementing his reputation as an authority on the region.

Masterworks and Recognition

Bridgman's dedication and evolving style led to significant recognition. His breakthrough came with the monumental painting The Funeral Procession of a Mummy on the Nile (sometimes titled The Funeral Rites of a Mummy), exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon of 1877. This ambitious work, depicting a solemn ancient Egyptian ritual unfolding under a dramatic sky, was a critical and popular sensation. Its grand scale, archaeological detail (drawing on his Egyptian travels), and masterful handling of light and composition captivated audiences.

The painting earned Bridgman considerable acclaim, including the Cross of the Legion of Honour, a high distinction from the French government. It was purchased by the prominent American newspaper publisher James Gordon Bennett Jr., a significant act of patronage. Decades later, in 1990, the painting was acquired by the noted American collector Wendell Cherry and subsequently donated to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, where it remains a centerpiece of their collection. This single work firmly established Bridgman's international reputation.

Beyond this famous masterpiece, Bridgman produced a rich body of work exploring various facets of North African life. A Street Scene in Algeria is considered one of his most iconic Orientalist images, capturing the vibrant atmosphere of a sun-drenched thoroughfare. An Afternoon in Algiers and On the Terrace (c. 1885) offer glimpses into moments of leisure and daily routine, often featuring women in domestic or courtyard settings. The Fountain Room (c. 1900) exemplifies his interest in depicting serene interior spaces, showcasing intricate tilework and the play of light.

His subjects ranged widely. Preparations for an Algerian Wedding (c. 1900) captures the anticipation of a significant cultural event. A Portrait of a Woman from Kabylia, Algeria (1875) demonstrates his skill in portraiture within an ethnographic context. He also tackled historical and mythological themes related to the region, such as the Procession of the Bull Apis, another scene drawn from ancient Egyptian religion. Occasionally, he painted European subjects, like An American Circus in Normandy, but his fame rested squarely on his Orientalist works. His consistent presence and success at the Paris Salon and other major exhibitions solidified his standing in the art world.

Bridgman and His Contemporaries

Frederick Arthur Bridgman operated within a vibrant and interconnected international art scene. His most crucial relationship was undoubtedly with his teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme's influence provided Bridgman with a strong academic foundation and directed him towards Orientalist themes, setting the stage for his career. However, Bridgman's departure towards a more naturalistic style shows he was also receptive to other artistic currents.

In Paris, Bridgman was part of a growing community of American expatriate artists. He associated with figures like Edwin Lord Weeks, another prominent American Orientalist painter who also traveled extensively in North Africa, Persia, and India. Weeks, like Bridgman, studied under Gérôme for a time. They shared similar interests in capturing exotic locales with accuracy and flair. Other American artists in Paris whose paths he might have crossed, even if their styles differed, include John Singer Sargent, known for his dazzling brushwork and society portraits but who also painted scenes from his travels, and Thomas Eakins, another Gérôme student who ultimately pursued a starkly different path of American Realism.

Within the French context, Bridgman would have been aware of, and likely competed with, established French Orientalists such as Eugène Fromentin, known for his atmospheric depictions of Algeria, and Gustave Guillaumet, who focused on the harsh realities and dignity of Algerian life. Gérôme's own studio produced other successful academic painters, like Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, who specialized in peasant scenes and later photographic-influenced realism.

Bridgman's evolving style, particularly his brighter palette and looser handling, suggests an awareness of artists who emphasized light and color. The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny, whose vibrant, sun-drenched scenes of Spanish and Moroccan life were highly influential in the 1870s, likely impacted Bridgman's approach to rendering brilliant light and texture. While Bridgman never became an Impressionist, he worked in Paris during the height of the movement and would have been exposed to the works of Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley. The Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, often painting outdoors, resonated with Bridgman's own move towards greater naturalism, even if he maintained a more solid sense of form and narrative structure derived from his academic training. He may also have absorbed influences from the earlier Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, admired for his sensitive handling of light in landscapes. Even artists with vastly different trajectories, like Paul Gauguin, were part of the broader Parisian milieu, though direct influence is less evident. Bridgman navigated these diverse influences, forging a style that balanced tradition and innovation.

Later Career and Stylistic Evolution

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Bridgman continued to enjoy considerable success. He maintained studios in Paris and Normandy, dividing his time between France and his travels. He remained a regular exhibitor in both Europe and the United States. His work was frequently shown at the National Academy of Design in New York, where exhibitions like the one in 1890 drew significant public attention, indicating his sustained popularity in his home country despite living abroad.

During the later part of his career, particularly from the 1890s onwards, the stylistic evolution noted earlier became more pronounced. Some sources suggest a clearer shift towards an Impressionistic handling of paint and light in his later works. While he never abandoned representational accuracy entirely, his brushwork could become quite free, and his focus often centered on capturing the sensory experience of a place—the heat, the light, the color—rather than solely on ethnographic or narrative detail. This later phase shows him continuing to adapt and respond to the changing artistic landscape, moving further from the tight finish of his early Gérôme-influenced period towards a more personal and painterly naturalism.

Despite these stylistic shifts, his primary subject matter remained rooted in his Orientalist experiences. He continued to revisit themes and sketches from his North African travels, producing variations on popular compositions and exploring new aspects of the cultures that fascinated him. His reputation as a leading Orientalist painter remained secure, even as artistic tastes began to shift towards Modernism in the early 20th century.

Art Market and Collections

Frederick Arthur Bridgman's work was highly sought after during his lifetime and continues to command significant attention in the art market today. His success at the Paris Salon and other international exhibitions translated into commercial success, with patrons and collectors in both Europe and America acquiring his paintings. The purchase of The Funeral Procession of a Mummy by James Gordon Bennett Jr. is a prime example of the high-level patronage he attracted.

In the contemporary art market, Bridgman's paintings regularly appear at major auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's in New York, London, and Paris. His works, particularly large-scale, well-preserved Orientalist scenes, often achieve strong prices, sometimes reaching into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. The enduring appeal of Orientalist art, combined with Bridgman's technical skill and recognizable name, ensures continued market interest. The story of Wendell Cherry acquiring The Funeral Procession in 1990 highlights the ongoing desirability of his major works among prominent collectors.

Reflecting his importance, Bridgman's paintings are held in the permanent collections of numerous prestigious museums, primarily in the United States. Key institutions include the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Speed Art Museum in Louisville (home to his most famous work). His presence in these major public collections ensures his art remains accessible for study and appreciation, solidifying his place within the canon of American art history. The distribution of his work across these institutions underscores his national significance.

Legacy and Influence

Frederick Arthur Bridgman left a lasting legacy as one of America's foremost Orientalist painters. His primary contribution lies in his ability to synthesize the rigorous discipline of French academic training with a more modern, naturalistic sensibility towards light and color. He effectively bridged the gap between the meticulous detail of Gérôme and the atmospheric concerns that were gaining prominence during his career. This unique blend resulted in works that were both informative and visually captivating.

His extensive travels and commitment to firsthand observation lent an air of authenticity to his depictions of North Africa and Egypt, influencing how these regions were perceived in the West. While operating within the broader framework of Orientalism—a genre now subject to post-colonial critique for its potential exoticization and stereotyping—Bridgman's focus often included sympathetic portrayals of daily life, particularly the lives of women, offering glimpses into domestic spaces and routines. Works like The Fountain Room showcase this interest in intimate, tranquil scenes alongside his grander historical or bustling street views.

Through his popular and critically acclaimed paintings, as well as his illustrated publications like Winters in Algeria, Bridgman significantly shaped American and European audiences' understanding and imagination of the Middle East and North Africa. He inspired subsequent generations of artists interested in similar themes or attracted by his vibrant, light-filled technique. While the vogue for academic Orientalism waned with the rise of Modernism, Bridgman's work remains a testament to the skill and ambition of American artists engaging with the international art world in the late 19th century. His ability to achieve widespread recognition abroad while retaining strong ties to the American art scene highlights the increasingly transatlantic nature of art during his era.

Conclusion

Frederick Arthur Bridgman carved a unique path in the art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. From his beginnings as an engraver's apprentice in New York to his celebrated status as a leading Orientalist painter based in Paris, his career was marked by ambition, dedication, and a deep engagement with the cultures he depicted. Trained by the formidable Jean-Léon Gérôme, he absorbed the lessons of French academicism but forged his own distinct style, characterized by meticulous detail combined with a vibrant palette and sensitivity to light that brought his exotic subjects to life. His extensive travels in North Africa provided a wealth of authentic material, resulting in iconic works like The Funeral Procession of a Mummy on the Nile. Bridgman's paintings captivated audiences on both continents, earning him numerous accolades and securing his place in major museum collections. He remains a key figure in the story of American art and the complex history of Orientalism, remembered for his technical mastery and his evocative portrayals of distant lands.