Andreas Cellarius stands as a fascinating and pivotal figure at the intersection of science, art, and education during the vibrant intellectual period of the 17th century. Though primarily known as an astronomer, mathematician, and cartographer, his most enduring legacy, the Harmonia Macrocosmica, is celebrated as much for its breathtaking artistic beauty as for its scientific content. As an art historian, examining Cellarius involves appreciating not only the technical skill of his celestial charts but also the rich cultural and aesthetic milieu of the Dutch Golden Age from which they emerged, a period that also saw the flourishing of masters like Rembrandt and Vermeer.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Andreas Cellarius, originally Andreas Keller, was born around 1596 in Neuhausen, a small town near Worms in the Electorate of Palatinate, part of the Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Germany). His early life is not extensively documented, but it is known that he received his education at the prestigious University of Heidelberg. This institution was a significant center of Calvinist learning and humanist scholarship, which would have exposed Cellarius to a rigorous curriculum encompassing classical languages, mathematics, and the burgeoning field of natural philosophy, including astronomy.

The period of his youth was one of considerable intellectual ferment and, unfortunately, increasing political and religious tension that would culminate in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). It is plausible that these tumultuous times influenced his later move to the more stable and intellectually liberal environment of the Netherlands. His education in Heidelberg would have familiarized him with the prevailing Ptolemaic geocentric model of the universe, but also with the revolutionary heliocentric theories of Nicolaus Copernicus, which were gaining traction among scholars.

A Career in the Netherlands: Educator and Scholar

By the early 1620s, Cellarius had relocated to the Netherlands, a nation then experiencing its Golden Age – a period of extraordinary wealth, scientific advancement, artistic flowering, and relative religious tolerance. He initially worked as a schoolmaster in Amsterdam, a bustling metropolis and a global center for trade, publishing, and cartography. His skills in mathematics and classical languages would have been highly valued in the Latin schools, which prepared young men for university or careers in commerce and administration.

Later, Cellarius moved to The Hague, the political center of the Dutch Republic. In 1637, he was appointed rector of the Latin School in Hoorn, a prosperous port city on the Zuiderzee. He would remain in Hoorn for the rest of his life, until his death in 1665. His position as rector indicates a respected standing within the community and a dedication to education. It was during his time in Hoorn that he undertook the monumental task of creating his celestial atlas. Beyond his cartographic work, Cellarius also authored other scholarly texts, including works on military fortifications and the history of Poland, often published by the renowned Amsterdam-based Janssonius publishing house, indicating his connections within the scholarly and publishing world of the time.

The Magnum Opus: Harmonia Macrocosmica

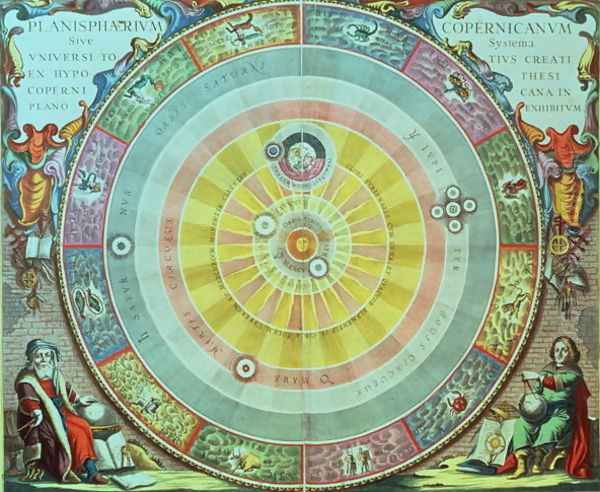

The crowning achievement of Andreas Cellarius's career is undoubtedly his Harmonia Macrocosmica, first published in 1660 by Johannes Janssonius in Amsterdam. This magnificent celestial atlas is widely regarded as one of the most spectacular and artistically ambitious works in the history of astronomical cartography. It was intended as part of a larger, two-volume cosmography, but the second volume, which was to cover terrestrial geography, was never completed.

The Harmonia Macrocosmica consists of a preface and 29 large, double-folio engraved plates, meticulously hand-colored in most surviving copies. These plates are not merely functional star charts; they are elaborate artistic compositions, rich in allegorical detail and Baroque ornamentation. The atlas is a visual encyclopedia of the cosmological theories known in the mid-17th century, presenting them with remarkable clarity and aesthetic appeal.

Cosmological Models Illustrated

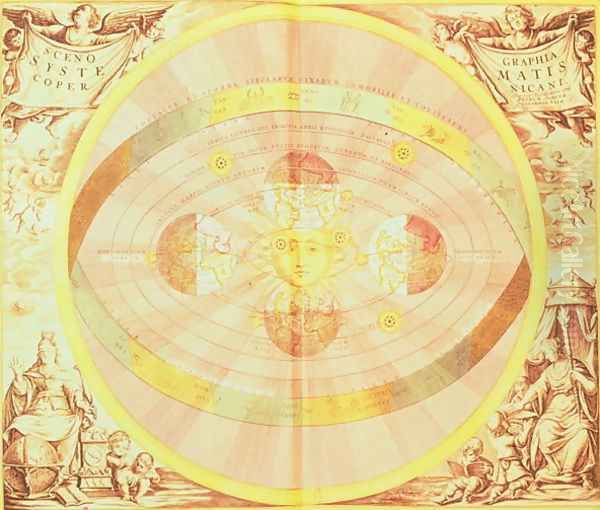

Cellarius's atlas is particularly valuable for its systematic depiction of competing world systems. It begins with plates illustrating the geocentric model of Claudius Ptolemy, which had dominated Western thought for over a_millennium. These plates show the Earth at the center, with the Sun, Moon, and planets orbiting it in complex crystalline spheres. The intricate epicycles and deferents of the Ptolemaic system are rendered with precision.

Following this, Cellarius presents the heliocentric system proposed by Nicolaus Copernicus in his 1543 work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. These plates dramatically shift the Sun to the center, with the Earth and other planets revolving around it. The Copernican plates often feature dynamic compositions, visually emphasizing the revolutionary nature of this model.

The atlas also includes plates dedicated to the Tychonic system, a hybrid model developed by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century. In Brahe's system, the planets orbit the Sun, but the Sun and Moon, in turn, orbit a stationary Earth. This model was an attempt to reconcile the mathematical advantages of the Copernican system with the perceived physical and scriptural objections to a moving Earth. Cellarius illustrates this complex arrangement with his characteristic clarity. He also includes variations, such as the semi-Tychonic system of Giovanni Battista Riccioli.

The Artistry of the Plates

From an art historical perspective, the Harmonia Macrocosmica is a masterpiece of Baroque visual culture. The engravers who translated Cellarius's designs onto copper plates (their identities are not definitively known, though some plates are attributed to Jan van Loon or Johannes van den Aveele) demonstrated exceptional skill. The plates are characterized by:

Rich Ornamentation: The celestial diagrams are often framed by elaborate cartouches, swags of fruit and flowers, cherubic figures (putti), personifications of winds, and allegorical representations of astronomers and muses. These decorative elements are typical of the Baroque love for opulence and drama.

Vibrant Hand-Coloring: While the coloring was typically done by specialized artisans after printing, the quality and vibrancy of the colors in many extant copies significantly enhance the visual impact of the plates. The use of gold leaf for stars and important celestial features adds to their splendor.

Dynamic Compositions: Many plates feature dynamic, almost theatrical compositions. Figures gesture dramatically, clouds billow, and celestial bodies seem to move across the page. This sense of movement and energy is a hallmark of Baroque art, seen in the works of painters like Peter Paul Rubens or sculptors like Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Integration of Science and Allegory: Cellarius masterfully blends scientific information with mythological and allegorical imagery. Constellations are depicted not just as patterns of stars but as the mythological figures they represent, rendered in classical style. For example, the plate "Haemisphaerium Stellatum Boreale Antiquum" shows the northern constellations with figures like Ursa Major and Draco in lively poses.

Christian Constellations: A particularly interesting set of plates depicts the "Christianized" constellations proposed by Julius Schiller in his Coelum Stellatum Christianum (1627). Schiller attempted to replace the traditional pagan mythological figures of the constellations with figures from Christian hagiography and biblical narratives. For instance, the twelve signs of the Zodiac were replaced by the twelve Apostles. While Schiller's system never gained widespread acceptance, Cellarius's inclusion of these plates provides a fascinating glimpse into the religious and cultural currents of the time, where attempts were made to reconcile new scientific discoveries with traditional Christian cosmology.

The overall effect is one of awe and wonder, inviting the viewer to contemplate the majesty and complexity of the cosmos. The atlas served not only as a scientific tool but also as a luxurious object of intellectual curiosity and aesthetic appreciation, suitable for the libraries of wealthy scholars, merchants, and nobles.

Publication and Later Editions

The Harmonia Macrocosmica was published by Johannes Janssonius, one of the leading figures in the competitive Amsterdam map trade, a contemporary and rival of the famed Blaeu family (Willem Janszoon Blaeu and his son Joan Blaeu), whose Atlas Maior was another monumental achievement of Dutch cartography. The initial 1660 edition was followed by a second edition in 1661. After Janssonius's death, the plates were acquired by other publishers. In 1708, Gerard Valk and Petrus Schenk the Elder, prominent Amsterdam map publishers, reissued the atlas with an updated title page and some minor alterations, attesting to its enduring popularity and relevance nearly half a century after its first appearance.

Other Works and Intellectual Pursuits

While the Harmonia Macrocosmica is his most famous work, Cellarius was a scholar with diverse interests. He published Architectura Militaris (1647), a treatise on military fortifications, a subject of considerable practical importance during an era marked by frequent warfare and advancements in siegecraft. His work on Polish history, Regni Poloniae, Magnique Ducatus Lituaniae (1652), demonstrates his engagement with contemporary European political geography. These works, also published by Janssonius, further underscore his scholarly reputation and his ability to synthesize and present complex information.

The Artistic and Scientific Context of the Dutch Golden Age

To fully appreciate Cellarius, one must place him within the extraordinary context of the Dutch Golden Age. This period, roughly spanning the 17th century, saw the Dutch Republic rise to become a global economic powerhouse, a center of scientific innovation, and a haven for artistic production.

Cartography in the Dutch Golden Age

Dutch cartography was unparalleled in the 17th century. The nation's maritime dominance, fueled by organizations like the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC), created an insatiable demand for accurate maps and charts. Amsterdam became the world's leading center for map production. Figures like:

Gerardus Mercator (though Flemish and earlier, his projection was foundational)

Abraham Ortelius (creator of the first true modern atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum)

Jodocus Hondius and his sons, Jodocus II and Henricus

Willem Janszoon Blaeu and his son Joan Blaeu (whose Atlas Maior was a pinnacle of terrestrial cartography)

Johannes Janssonius (Cellarius's publisher and a major competitor to the Blaeus)

all contributed to this cartographic excellence. Cellarius's work extended this tradition into the celestial realm, applying the same high standards of engraving, printing, and artistic embellishment to the heavens.

Art in the Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age was also a golden age for painting. While Cellarius was not a painter, the visual culture of his time undoubtedly influenced the aesthetic choices in his atlas. This era produced an astonishing number of talented artists, including:

Rembrandt van Rijn: Master of light and shadow, psychological portraiture, and biblical scenes.

Johannes Vermeer: Known for his serene interior scenes, exquisite use of light, and meticulous detail.

Frans Hals: Celebrated for his lively and expressive portraits.

Jan Steen: Famous for his humorous and moralizing genre scenes.

Jacob van Ruisdael: A leading landscape painter, capturing the Dutch countryside with atmospheric depth.

Pieter de Hooch: Another master of tranquil domestic interiors and courtyards.

Aelbert Cuyp: Known for his idyllic landscapes bathed in golden light.

Rachel Ruysch and Judith Leyster: Notable female painters, with Ruysch specializing in flower still lifes and Leyster in genre scenes and portraits.

Willem Kalf: Renowned for his opulent still life paintings (pronkstilleven).

Gerard ter Borch: Elegant genre scenes and portraits.

The Dutch art market was unique, with a broad middle-class clientele purchasing art. This led to a specialization in genres like portraits, landscapes, seascapes, still lifes, and genre scenes. Common threads in Dutch art included a keen observation of reality, meticulous attention to detail, and often, an underlying moral or symbolic meaning. Cellarius's atlas, with its precision, detail, and symbolic richness, shares these characteristics, albeit in a scientific and cartographic medium. The desire to understand and represent the world, whether the immediate surroundings or the distant cosmos, was a powerful cultural force.

The Scientific Revolution's Influence

Cellarius worked during the height of the Scientific Revolution. The groundbreaking work of Copernicus, Johannes Kepler (with his laws of planetary motion), and Galileo Galilei (whose telescopic observations provided strong evidence for the Copernican model) was transforming humanity's understanding of the universe. While Cellarius himself was not a primary discoverer, his Harmonia Macrocosmica played a crucial role in disseminating these new ideas to a wider, educated audience. By visually comparing the different cosmological systems, he facilitated understanding and debate. His atlas is a testament to an era grappling with profound shifts in its worldview, moving from an ancient, Earth-centered cosmos to a modern, Sun-centered one.

Cellarius's Artistic Style in Detail: A Baroque Vision of the Cosmos

The artistic style of Cellarius's Harmonia Macrocosmica is firmly rooted in the Baroque. This is evident in several key aspects:

Drama and Grandeur: The scale of the plates, the richness of the ornamentation, and the dynamic portrayal of celestial phenomena all contribute to a sense of drama and grandeur. The universe, as depicted by Cellarius, is not a static, abstract entity but a vibrant, awe-inspiring theater.

Elaborate Allegory: The use of allegorical figures – astronomers with their instruments, muses, personifications of scientific concepts – is a common Baroque device used to convey complex ideas in a visually engaging manner. These figures often adopt classical poses and attire, reflecting the ongoing influence of Renaissance humanism.

Symmetry and Order: Despite the dynamism, many of Cellarius's plates exhibit a strong sense of symmetry and underlying order, reflecting the belief in a divinely ordained, harmonious universe. This is particularly evident in the framing elements and the arrangement of diagrams.

Horror Vacui (Fear of Empty Space): Characteristic of much Baroque design, Cellarius's plates often fill every available space with decorative elements, text, or subsidiary diagrams. This creates a visually dense and rich surface that invites close examination.

Theatricality: The way celestial systems are presented, often with figures looking on or pointing, gives the plates a theatrical quality, as if the viewer is witnessing a grand cosmic performance. This aligns with the Baroque fascination with spectacle and illusion.

The artists who engraved Cellarius's designs were masters of their craft, capable of rendering fine detail, varied textures, and a sense of depth and volume. The interplay of light and shadow in the engravings, even before the application of color, contributes to their three-dimensional quality. The figures are often muscular and animated, reminiscent of the heroic figures in Baroque painting and sculpture.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Andreas Cellarius died in Hoorn in 1665, just a few years after the initial publication of his masterpiece. While his name might not be as widely known as some of his scientific contemporaries like Galileo or Kepler, or artistic giants like Rembrandt, his Harmonia Macrocosmica has secured his place in history.

The atlas is treasured by collectors, historians of science, and art enthusiasts alike. Original copies command high prices at auction. Its plates are frequently reproduced in books, exhibitions, and documentaries related to astronomy, cartography, and the history of science. The beauty and intellectual depth of Cellarius's work continue to inspire.

His contribution was recognized in a modern astronomical context when, in 1997, the asteroid 12618 Cellarius was named in his honor by the International Astronomical Union. This celestial tribute is a fitting acknowledgment of a man who dedicated so much of his life to charting the heavens.

The Harmonia Macrocosmica remains a powerful testament to a pivotal moment in human history when our understanding of the universe was undergoing a profound transformation. It captures the excitement, the intellectual debates, and the artistic sensibilities of the 17th century. Cellarius's genius lay in his ability to synthesize complex scientific ideas and present them in a visually stunning and accessible format, creating a work that is both a scientific document and an enduring work of art.

Conclusion: A Harmonious Vision

Andreas Cellarius was more than just a school rector or a compiler of astronomical data. He was a visionary who understood the power of images to convey knowledge and inspire wonder. His Harmonia Macrocosmica is a symphony of science and art, a product of the unique intellectual and cultural environment of the Dutch Golden Age. It stands as a bridge between ancient cosmologies and the dawn of modern astronomy, rendered with a Baroque flourish that continues to captivate and educate.

As art historians, we can see in Cellarius's work the same dedication to craftsmanship, the same pursuit of beauty, and the same desire to understand and represent the world that characterized the great painters and artisans of his era. His celestial charts are not merely diagrams; they are windows into the 17th-century mind, reflecting its anxieties, its aspirations, and its boundless curiosity about the "Harmony of the Great Universe." His legacy is a reminder that science and art are not mutually exclusive domains but can, in the hands of a master like Cellarius, combine to create works of profound and lasting significance.