Ángel Zárraga Argüelles stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century art. A Mexican painter whose career largely unfolded in Europe, Zárraga navigated the complex currents of modernism, blending classical sensibilities with avant-garde exploration. His life and work offer a fascinating study of cultural exchange, artistic evolution, and the enduring power of personal conviction, particularly evident in his religious and figurative compositions. Born into a changing Mexico and matured in the artistic crucible of Paris, Zárraga forged a unique path, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both his heritage and his cosmopolitan experiences.

Early Life and Formative Years in Mexico

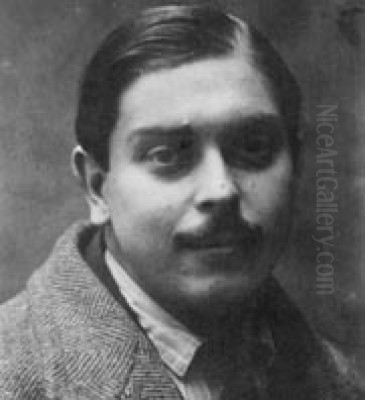

Ángel Zárraga Argüelles was born on August 16, 1886, in Victoria de Durango, located in the state of Durango, Mexico. His background was one of relative privilege; his father, Dr. Fernando Zárraga Guerrero, was a respected physician, and his mother hailed from the prominent Argüelles family. This environment likely provided him with the means and encouragement to pursue his artistic inclinations from a young age.

He received his initial art education within Mexico, studying at the renowned Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Academy of Fine Arts, previously the Academy of San Carlos) in Mexico City. This institution was the traditional center for artistic training in the country, steeped in European academic traditions. Here, Zárraga would have honed his foundational skills in drawing and painting, likely working within the prevailing realist and symbolist modes popular at the turn of the century. His talent was recognized early on, setting the stage for further development abroad.

The European Sojourn: Education and Exposure

In 1904, at the age of 18, Zárraga embarked on a pivotal journey to Europe, a common path for aspiring Latin American artists seeking advanced training and exposure to the latest artistic trends. His travels were extensive, taking him through Spain, Belgium, Italy, and ultimately, France. This period was crucial for broadening his artistic horizons and absorbing diverse influences.

In Spain, he likely encountered the works of contemporary masters such as Ignacio Zuloaga and Joaquín Sorolla, whose powerful realism and vibrant depictions of Spanish life were internationally acclaimed. In Italy, particularly Florence, he immersed himself in the art of the Renaissance, studying the works of masters like Giotto. The structural solidity and emotional depth of early Italian painting would leave a lasting impression on his later work, especially his murals and religious compositions. His time in Florence included exhibitions at venues like the Piazze Donatello.

His European travels also included participation in significant exhibitions, such as the prestigious Biennale di Venezia in Venice, further integrating him into the continental art scene. However, it was Paris that would become his long-term home and the primary center of his artistic activity.

Paris: The Crucible of Modernism

Zárraga settled in Paris around 1911, remaining there for the better part of the next three and a half decades. The French capital was the undisputed epicenter of the art world, buzzing with revolutionary movements like Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism. Zárraga arrived as Impressionism was solidifying its legacy and Post-Impressionism, particularly the work of Paul Cézanne, was profoundly influencing the younger generation.

During his time in Paris, Zárraga absorbed these influences, integrating elements of Impressionism and, more significantly, Cubism into his evolving style. He did not become a doctrinaire follower of any single movement but rather synthesized various approaches to create his own distinct visual language. He engaged with the Parisian art community, forming friendships, such as with fellow Mexican artist Roberto Montenegro, and interacting with French artists, evidenced by his later Portrait of Pierre Bonnard.

His Parisian years were marked by significant creative output and growing recognition in European circles. He exhibited regularly in Parisian salons and galleries, establishing a reputation for his technical skill and the unique blend of modern aesthetics with classical and religious undertones.

Evolving Artistic Styles: From Realism to a Personal Modernism

Zárraga's artistic journey reflects a dynamic evolution through several stylistic phases. His early work, grounded in his academic training and influenced by Spanish realism, emphasized accurate representation, detailed observation, and often, a bright, luminous palette. Works like Old Man in the Temple (1906) exemplify this initial phase.

His exposure to European modernism prompted a shift. He experimented with the broken brushwork and light effects of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. A key development was his engagement with Cubism. While influenced by the geometric deconstruction pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Zárraga's Cubism was often more tempered, retaining a strong figurative base and a sense of volume and structure that perhaps owed as much to Cézanne and Renaissance masters as to analytical Cubism. Some critics described his approach as a form of "humanized deconstruction," suggesting a less radical break with representation compared to his avant-garde contemporaries.

Later in his career, particularly in the 1920s and 30s, Zárraga developed a style often associated with the "Return to Order" movement that emerged after World War I. This phase saw a renewed interest in classicism, characterized by solid forms, clear compositions, and a sense of monumental dignity. His work integrated elements of Neoclassicism and even Art Deco sensibilities, visible in the stylized figures and balanced structures of his murals and easel paintings from this period. He sometimes employed techniques like pointillism within these classically inspired compositions, demonstrating a continued interest in optical effects alongside formal rigor.

Thematic Focus: Religion and Spirituality

A defining characteristic of Ángel Zárraga's oeuvre is his profound and enduring engagement with religious themes. Raised in a Catholic country and deeply spiritual himself, he frequently turned to Christian iconography and narratives throughout his career. This focus set him somewhat apart from many of his modernist contemporaries, who often eschewed traditional religious subjects.

His religious works include easel paintings and, significantly, large-scale murals. One of his earliest notable religious pieces is Ex-voto (The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian), painted around 1910-1911. This work, depicting the suffering saint, showcases his early mastery of figurative painting and foreshadows his later dedication to sacred art.

In Paris, Zárraga undertook major mural commissions for several churches. He decorated the crypt of Notre Dame de la Salette (completed around 1924) and created significant works for the Vert-Cœur church and the chapel of the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris (Chapelle des étudiants). These murals often involved collaboration with other artisans, including sculptors, stained-glass artists, and architects, highlighting his ability to work within larger decorative programs. His murals are characterized by their compositional clarity, stylized figures reminiscent of early Renaissance frescoes, and a palpable sense of devotion. He also painted murals depicting figures like Joan of Arc.

Upon his return to Mexico later in life, he continued this focus, undertaking commissions such as murals for the Monterrey Cathedral. Despite the high quality of these works, some of his religious murals, particularly those with potentially sensitive political undertones in post-revolutionary Mexico, were not always widely celebrated or preserved.

Thematic Focus: The Human Form and Modern Life

Beyond religious subjects, Zárraga was a skilled portraitist and depicted various aspects of modern life, often focusing on the human figure. His portraits capture the likeness and character of his sitters, ranging from formal commissions to more intimate portrayals of friends and fellow artists, such as the aforementioned portrait of Pierre Bonnard. Poetess (1917) is another example of his sensitive figure painting from this period.

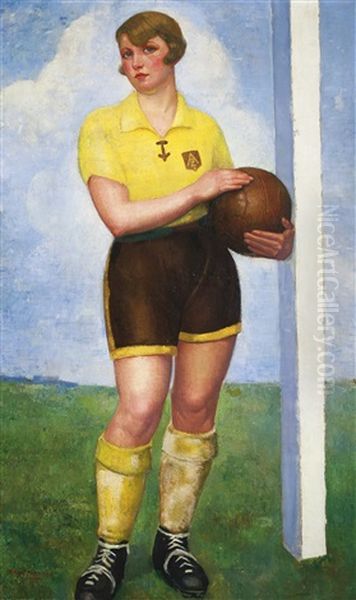

A particularly distinctive aspect of his work is his fascination with sports, especially football (soccer). In the 1920s, he created a series of paintings depicting footballers, notable for their dynamic compositions, muscular figures, and celebration of physical prowess. These works capture the energy and modernity of sport. Las Futbolistas (The Footballers, 1922) is perhaps the most famous of these, a powerful composition that earned him recognition, including an Olympic medal when exhibited during the art competitions associated with the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. Heading Soccer Study (1926) further demonstrates his exploration of athletic movement and form.

His depictions of the human body extended to nudes, such as Nude Dancer (1909) and Baigneuse, côte d'emaire (Bather, coast of emaire, 1936). These works often combine classical ideals of form with modern stylistic treatments, showcasing his ability to render the figure with both anatomical accuracy and expressive power.

Major Works and Exhibitions

Throughout his career, Zárraga produced a substantial body of work and participated in numerous important exhibitions. Key works that represent the breadth of his output include:

Old Man in the Temple (1906): Representative of his early realist phase.

Nude Dancer (1909): Early exploration of the figure.

Ex-voto (The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian) (c. 1910-11): Significant early religious work.

Poetess (1917): Example of his portraiture and figure painting during his Parisian years.

Las Futbolistas (1922): Iconic work from his sports series, celebrated internationally.

Murals for Notre Dame de la Salette, Paris (c. 1924): Major religious mural cycle.

Heading Soccer Study (1926): Further exploration of the football theme.

Portrait of Pierre Bonnard: Documenting his connection to the French art scene.

Baigneuse, côte d'emaire (1936): Later example of his figurative work.

Murals for the Mexican Embassy in Paris: A prestigious commission reflecting his standing.

Murals for the Bankers' Club (Club de Banqueros) and Monterrey Cathedral, Mexico: Later commissions upon his return.

His exhibition record highlights his integration into both Mexican and European art circles. He debuted at the Academy of Fine Arts exhibition in Mexico City in 1907. In Europe, he showed work in Florence, the Venice Biennale, and frequently in Paris, including group exhibitions alongside artists like Valentino Zilibelli and Giorgio de Chirico. His participation in the Olympic art competition underscores the international reach of his work during the interwar period.

Collaborations and Artistic Circle

While often working independently, Zárraga's career involved interaction and collaboration with other creative figures. His friendship with fellow Mexican expatriate Roberto Montenegro in Paris suggests a supportive network among Mexican artists abroad. His portrait of Pierre Bonnard indicates direct contact with leading figures of the French art establishment.

His most extensive collaborations likely occurred in the context of his large-scale mural projects for churches and public buildings. These inherently collaborative endeavors required working alongside architects, sculptors (whose names are often unrecorded in relation to Zárraga's specific projects), stained-glass artists, and other craftsmen to realize a unified decorative scheme. This demonstrates a capacity for teamwork and an understanding of how painting integrates with other art forms within an architectural space.

His influences connect him to a wider circle: the Spanish realists Ignacio Zuloaga and Joaquín Sorolla shaped his early development; Renaissance masters like Giotto provided enduring inspiration for structure and narrative; Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne informed his sense of form; and Cubists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque impacted his approach to representation, even as he maintained his own path. He existed within a broad artistic milieu that included figures ranging from the Nabis (like Bonnard) to metaphysical painters (like De Chirico) and other modernists navigating the interwar period.

Later Years and Return to Mexico

The outbreak of World War II significantly impacted life in Europe and prompted Zárraga to return to Mexico in 1941, after more than three and a half decades abroad. His return marked a new phase, but also one fraught with challenges. While he received some commissions, such as the murals for the Bankers' Club and Monterrey Cathedral, he faced financial difficulties and declining health.

Anecdotally, it's known that during his long stay in Paris, he experienced periods of hardship, including a bout of pneumonia from which he recovered thanks to the care of a Russian friend. Despite his reputation in Europe, he was not as widely known or perhaps fully embraced by the dominant currents of Mexican art upon his return. The Mexican art scene was heavily influenced by the Muralist movement led by figures like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, whose focus on nationalistic, social, and political themes differed significantly from Zárraga's more cosmopolitan and often religiously-inflected modernism.

There's a story that he declined an invitation to participate in the large-scale government-sponsored mural projects in Mexico City's public buildings, perhaps indicating a reluctance to engage with the prevailing political climate or a commitment to his own artistic direction. His final years were marked by these struggles, a poignant contrast to the recognition he had achieved in Europe.

Ángel Zárraga Argüelles passed away in Mexico City on September 22, 1946, at the age of 59.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Ángel Zárraga's position in art history is complex. He is recognized as a pioneer of Mexican modernism, one of the first of his generation to engage deeply with European avant-garde movements. His work demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of artistic tradition, from the Renaissance to modernism, and an ability to synthesize these influences into a personal style.

His contributions as a muralist, particularly in the realm of religious art, are significant, offering a counterpoint to the more secular and politically charged murals of his famous contemporaries Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros. His dedication to religious themes throughout the modernist era is noteworthy in itself.

However, his long expatriation meant that his influence within Mexico was perhaps less direct than that of artists who remained or returned earlier. His style, often characterized by classical restraint and European refinement, did not always align with the indigenist and nationalist currents that became dominant in Mexican art during the mid-20th century. Consequently, his work was sometimes marginalized or less studied within his home country compared to his European reputation.

Today, Zárraga is increasingly appreciated for the unique bridge he represents between European modernism and Mexican artistic identity. His paintings, particularly the footballer series and his elegant figurative works, are sought after, and his murals are studied for their artistic merit and historical context. He is seen as an artist who navigated the complexities of tradition and innovation, faith and modernity, national identity and cosmopolitanism, leaving a legacy rich in technical skill, thematic depth, and cross-cultural dialogue. His work continues to resonate as a testament to an artistic journey that spanned continents and artistic revolutions.

Conclusion

Ángel Zárraga Argüelles was more than just a Mexican painter who lived in Paris; he was an artist whose life embodied the transatlantic dialogues shaping modern art. From his academic roots in Mexico City to his immersion in the avant-garde circles of Europe, he forged a path marked by technical brilliance, stylistic evolution, and a steadfast commitment to his personal vision. Whether depicting the sinewy grace of athletes, the serene dignity of religious figures, or the intimate character of a portrait, Zárraga's work consistently reveals a mastery of form and a deep engagement with the human condition. Though perhaps overshadowed at times by more famous contemporaries, his unique synthesis of classicism, modernism, and spirituality secures his place as a distinctive and important voice in 20th-century art history.