Heinrich Nauen stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century German art. A painter, printmaker, and creator of monumental works, his career navigated the turbulent currents of modernism, leaving a distinct mark particularly associated with the vibrant artistic developments in the Rhineland. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the evolution of Expressionism in Germany, its regional variations, and the challenges faced by artists during a period of profound social and political change.

Origins and Artistic Awakening

Born on June 1, 1880, in Krefeld, Germany, Heinrich Nauen's roots were firmly planted in the Rhineland region, an area that would remain central to his identity and artistic output throughout his life. Krefeld, a city known for its textile industry but also fostering a growing cultural scene, provided the initial backdrop for his formative years. His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training, a path common for aspiring artists of his generation seeking to master the technical foundations of their craft.

His educational journey took him first to Munich, a major artistic hub in Germany at the time. There, he enrolled in the private painting school run by Heinrich Knirr. Munich offered exposure to various contemporary trends, but Nauen's path soon led him elsewhere. He continued his studies in Stuttgart under the tutelage of Leo von Kalckreuth at the State Academy of Fine Arts. However, reports suggest Nauen found the academic approach there unsatisfying, hinting at an early desire for a more personal and perhaps more modern mode of expression than traditional academic training offered.

This period of formal education, though perhaps not entirely fulfilling in its later stages, equipped Nauen with essential skills. Yet, his dissatisfaction likely fueled his search for a more authentic artistic voice, pushing him towards the emerging styles that were challenging academic conventions across Europe. His eventual return and settling in the Rhineland, particularly his connection to the Krefeld art scene, proved crucial for his subsequent development.

Embracing Modernism: Influences and Early Style

The early years of the 20th century were a period of intense artistic experimentation. Like many artists of his generation, Nauen absorbed the influences of the revolutionary movements unfolding, particularly in France. The impact of Post-Impressionism and Fauvism was profound. The provided texts specifically highlight the significant influence of two masters: Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse.

Van Gogh's expressive brushwork, intense emotionality, and bold use of color resonated deeply with artists seeking to break free from naturalistic representation. Nauen himself acknowledged Van Gogh's powerful, sometimes even described as "oppressive," influence on his own developing style. This suggests a period of intense engagement, perhaps even struggle, as Nauen worked to integrate Van Gogh's innovations without losing his own artistic identity.

Henri Matisse, a leading figure of Fauvism, offered another potent source of inspiration. Matisse's liberation of color, using it not just descriptively but emotionally and decoratively, and his simplification of form, provided a pathway towards a more subjective and visually striking art. The emphasis on flat planes of color and strong outlines found in Fauvism can be seen echoed in Nauen's work.

Beyond these modern French masters, the influence of earlier artists is also noted. The mention of a "Rubens-esque" quality suggests an appreciation for the dynamism, rich color, and perhaps the compositional energy of the Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens. This connection, though less typical for an Expressionist, points to Nauen's broad artistic interests and his potential synthesis of historical and modern influences. Furthermore, for his religious works, an influence from the intense spirituality and elongated forms of El Greco has been suggested.

Initially, Nauen's work showed leanings towards Neo-Impressionism, a style characterized by a more systematic application of color theory than Impressionism. However, his engagement with the expressive potential demonstrated by Van Gogh and Matisse propelled him towards a more vigorous and emotionally charged style. This evolution laid the groundwork for his central role in Rhenish Expressionism.

The Heart of Rhenish Expressionism

While Expressionism manifested in various forms across Germany, notably with groups like Die Brücke in Dresden and Der Blaue Reiter in Munich, the Rhineland developed its own distinct flavour. Heinrich Nauen emerged as one of the leading figures of this regional movement, known as Rheinische Expressionismus. This movement, while sharing the broader Expressionist goals of subjective expression and emotional intensity, often displayed specific characteristics tied to the region.

Rhenish Expressionism frequently drew inspiration from the local landscape – the Rhine river, the surrounding countryside, and rural life. There was often a lyrical, sometimes decorative quality to the work, perhaps less angular and aggressive than some forms of Expressionism found elsewhere in Germany. Color remained paramount, often bright, luminous, and applied with vigour.

Nauen was deeply involved in the activities of this group. He formed close friendships and artistic alliances with other key Rhenish artists, including August Macke, known for his poetic and colourful depictions of modern life, and Heinrich Campendonk, whose work often featured mystical and folk-art elements. Max Ernst, who would later become a central figure in Dada and Surrealism, was also associated with this circle in his early, Expressionist phase.

A pivotal moment for the group was the "Ausstellung Rheinischer Expressionisten" (Exhibition of Rhenish Expressionists) held in Bonn in 1913. Nauen was a prominent participant, showcasing his work alongside Macke, Campendonk, and others. This exhibition helped to define and solidify the identity of Rhenish Expressionism as a significant force within German modern art, demonstrating its unique contribution to the broader Expressionist movement. Nauen's participation cemented his position as a leader within this regional avant-garde.

Artistic Production: Diversity and Themes

Heinrich Nauen's artistic output was remarkably diverse, extending far beyond easel painting. He was a prolific creator across various media, demonstrating a commitment to exploring different forms of artistic expression and integrating art into broader contexts. His oeuvre included paintings, watercolors, numerous prints, large-scale murals, mosaics, and works of applied art.

His paintings often focused on traditional genres like landscape, portraiture, and still life, but interpreted through his vibrant Expressionist lens. Landscapes, particularly those depicting the Rhineland and the Ruhr area, were a recurring theme. Works like Landscape with Woodpile exemplify his approach during his mature phase: influenced by Van Gogh and Matisse, they feature bright, often non-naturalistic colors, bold compositions, and an energetic application of paint that conveys the artist's subjective experience of the scene rather than a purely objective rendering. The depiction of rural life, as seen in Farmer Harvesting, also reflects this connection to the regional environment.

Portraiture and figure studies also formed a significant part of his work. Knieendes und sich vorbeugendes Mädchen (Kneeling and Bending Girl) from 1905 suggests an early interest in capturing mood and emotion through the human form, rendered with a quiet sensitivity. Later works continued this exploration, often imbued with the expressive intensity characteristic of his style.

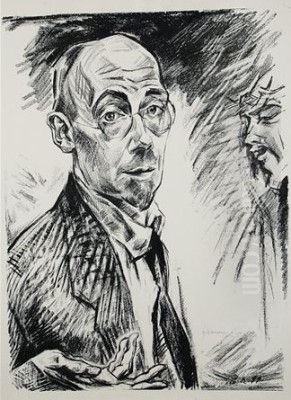

Nauen was also a highly accomplished printmaker. Printmaking was a crucial medium for many Expressionists, valued for its directness, potential for stark contrasts, and ability to disseminate images more widely. Nauen worked in various techniques, producing woodcuts, lithographs, and etchings. His print series Die Judenbuche (The Jew's Beech), comprising ten original prints illustrating Annette von Droste-Hülshoff's novella, is a notable example of his work in this field. The print Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child) from 1919 reflects the emotional tenor of the post-World War I era, a common theme among artists grappling with the war's aftermath. His skill in printmaking solidified his reputation as one of the foremost graphic artists within Rhenish Expressionism.

His engagement with monumental art, including murals and mosaics, points to an interest in integrating art with architecture and public spaces. This aligns with the broader aims of movements like the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation), with which Nauen had connections. The Werkbund sought to bridge the gap between art, craft, and industry, promoting high-quality design in all aspects of life. Nauen's involvement in creating large-scale works reflects this ambition to move art beyond the confines of the gallery.

Religious and biblical themes also appeared in Nauen's work. His creation of large Madonna figures, sometimes noted for their connection to Gothic traditions or the intensity of El Greco, indicates a spiritual dimension to his art, exploring profound themes of faith and humanity through his modern visual language.

Connections and Wider Artistic Context

Nauen did not operate in isolation. His career intersected with several important artistic organizations and broader movements that shaped modern art in Germany. His association with the Rhenish Expressionists was central, but his connections extended further.

He was linked to the Sonderbund, specifically the "International Sonderbund Exhibition" held in Cologne in 1912 (though the provided text mentions a 1914 Cologne exhibition, the major Sonderbund show was 1912, famous for its impact). The Sonderbund exhibitions were crucial for introducing German audiences to international modern art, particularly French Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, and Nauen's proximity to this milieu underscores his engagement with the forefront of European art.

His connection with the Deutscher Werkbund, founded in 1907, is also significant. The Werkbund's ideals of quality craftsmanship, functional design, and the unification of art and industry were influential. Nauen's own work in applied arts and monumental decoration resonates with the Werkbund's goals. These efforts to break down hierarchies between fine and applied arts were precursors to the later, more radical integration pursued by the Bauhaus school.

While primarily identified with Expressionism, the mention of New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) in relation to Nauen warrants careful consideration. New Objectivity emerged in the 1920s, partly as a reaction against Expressionism's subjectivity, favoring a more sober, realistic, and often socially critical style. The provided text notes no direct evidence of Nauen being a core figure of New Objectivity. However, it's plausible that the changing artistic climate of the Weimar Republic, where New Objectivity became prominent, might have had some subtle influence on his later work, perhaps tempering some of the earlier Expressionist fervor with a greater attention to realistic detail or structure, although his fundamental style remained rooted in Expressionism.

His relationships with individual artists were crucial. Beyond his Rhenish colleagues like Macke and Campendonk, his association with figures like Johan Thorn Prikker, a Dutch artist active in Germany known for his work in Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and later monumental art, highlights the cross-pollination of ideas. Christian Rohlfs, an older artist associated with Expressionism, was another figure within Nauen's orbit. These connections illustrate the network of artists contributing to the dynamic German art scene of the time.

The Shadow of the Nazi Regime

The rise of the Nazi party in 1933 cast a dark shadow over modern art in Germany. The regime actively suppressed avant-garde art, which it deemed "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst) – un-German, Jewish, Bolshevik, or simply incomprehensible and therefore dangerous. Artists associated with Expressionism, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, New Objectivity, and abstraction were targeted.

Heinrich Nauen, despite his focus on traditional subjects like landscape and his roots in German regionalism, was classified as a "degenerate" artist. His Expressionist style – the subjective use of color, the distortion of form for emotional effect – was antithetical to the Nazis' prescribed heroic realism. His works were likely removed from public collections, and he would have faced restrictions on his ability to exhibit and possibly even to work.

His association with other artists persecuted by the regime, such as Christian Rohlfs and Johan Thorn Prikker, further situated him within the circle of artists deemed undesirable by the Nazis. This period represented a profound crisis for modern artists in Germany, forcing many into exile, internal emigration, or silence. For Nauen, it meant the official rejection and suppression of the very artistic principles he had championed.

Tragically, beyond the political persecution, Nauen also suffered personal loss related to the era's turmoil. A significant portion of his work was reportedly destroyed during an Allied air raid in 1943, three years after his death. This loss compounded the damage inflicted by the Nazi regime, erasing part of his artistic legacy.

Teaching and Legacy

Beyond his own creative output, Heinrich Nauen contributed to the development of German art as an educator. He held a teaching position, likely at an art academy, where he influenced a younger generation of artists. The mention of Gerhard Fietz as one of his students points to this pedagogical role. Fietz himself became an artist associated with post-war German abstraction, suggesting that Nauen's teaching may have fostered experimentation and individual development.

Nauen's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered primarily as a key proponent of Rhenish Expressionism, contributing significantly to its distinct character through his vibrant paintings, powerful prints, and engagement with diverse media. His work captured the spirit of his time and place, translating the landscapes and life of the Rhineland into a modern, expressive visual language.

Despite the disruptions of the Nazi era and the subsequent destruction of some of his work, his importance has been recognized by art history. His works are held in museum collections, including the Clemens Sels Museum in Neuss and the Kunstmuseum Bonn, institutions dedicated to preserving and showcasing the art of the region and the period. Exhibitions featuring his work continue to affirm his place within the canon of German Expressionism.

He navigated the complex transition from late Impressionist influences to a fully formed Expressionist style, synthesizing international trends with regional sensibilities. His willingness to work across different media, from intimate prints to large-scale public art, speaks to a broad artistic vision. While perhaps overshadowed internationally by figures from Die Brücke or Der Blaue Reiter, Heinrich Nauen remains an essential figure for understanding the richness and diversity of modern art in Germany.

Heinrich Nauen passed away on November 26, 1940, in Kalkar, near his birthplace of Krefeld. His life spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and devastating political upheaval. Through it all, he maintained a commitment to his expressive vision, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its vibrant color, emotional depth, and deep connection to the Rhenish landscape. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of regional artistic identity within the broader sweep of European modernism.