Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Triosson stands as a pivotal figure in French art history, an artist whose career navigated the turbulent waters from the twilight of the Ancien Régime, through the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire, into the Bourbon Restoration. Born on January 5, 1767, in Montargis, and passing away in Paris on December 9, 1824, Girodet is celebrated for his unique artistic vision that masterfully blended the rigorous discipline of Neoclassicism, learned under the tutelage of the great Jacques-Louis David, with the burgeoning emotional intensity and imaginative freedom of early Romanticism. His work is characterized by technical brilliance, innovative compositions, and a distinct, often enigmatic, sensibility that set him apart from his contemporaries.

Often referred to simply as Girodet-Trioson, his full name reflects his later adoption by his guardian, Dr. Benoît-François Trioson. His journey as an artist was marked by early success, profound personal experiences during revolutionary times, and the creation of iconic images that continue to fascinate and provoke discussion. He was a painter of complex historical allegories, sensitive portraits, and mythological scenes imbued with a novel sensuality and psychological depth, making him a crucial precursor to the full flowering of the Romantic movement in France.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Anne-Louis Girodet's path to becoming a painter was not initially straightforward. Born into a respectable family in Montargis, his early life was marked by the loss of his parents. His father passed away when he was young, and his mother followed some years later. His upbringing and education were subsequently overseen by a distinguished physician, Dr. Benoît-François Trioson, who acted as his guardian and whose name Girodet would later add to his own. Dr. Trioson ensured the young man received a solid classical education.

Initially, Girodet pursued studies in architecture, reflecting perhaps a more conventional career path. He also reportedly showed interest in military pursuits and literature, demonstrating a breadth of intellectual curiosity early on. However, his true passion lay in the visual arts. He began his formal art training under a painter named Luquin before moving to Paris to further his ambitions.

In Paris, he briefly studied under the visionary architect Étienne-Louis Boullée, whose grandiose and often unbuilt designs might have influenced Girodet's later sense of scale and drama. However, the decisive moment in his artistic education came around 1784 or 1785 when he entered the prestigious studio of Jacques-Louis David. At this time, David was the undisputed leader of the Neoclassical school in France, his studio a crucible for the next generation of artistic talent.

The Influence of David and Early Success

Entering David's studio placed Girodet at the very center of the Parisian art world. David's teaching emphasized rigorous drawing based on classical sculpture and the human form, clarity of composition, and the depiction of lofty historical or mythological subjects intended to convey moral virtue. Girodet proved to be an exceptionally gifted pupil, quickly mastering the technical demands of the Neoclassical style.

He worked alongside other talented students who would also make significant marks on French art, including Antoine-Jean Gros, François Gérard, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (though Ingres arrived later), and Jean-Germain Drouais. The competitive yet stimulating environment fostered rapid development. Girodet distinguished himself not only through his technical skill but also through a burgeoning individuality that hinted at a departure from strict Davidian orthodoxy.

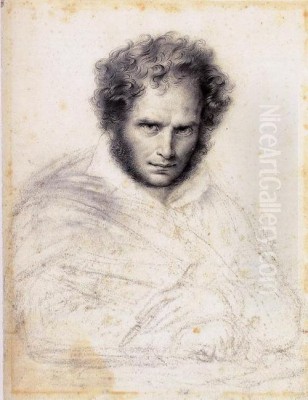

His talent was formally recognized in 1789, a year fraught with revolutionary significance, when he won the highly coveted Prix de Rome. This prestigious prize, awarded by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, granted the winner a funded period of study at the French Academy in Rome. Girodet's winning painting, Joseph Recognized by His Brothers, demonstrated his mastery of Neoclassical composition and draftsmanship, fulfilling the expectations of the Academy while perhaps already hinting at a greater emotional resonance than typical of the school.

The Italian Sojourn and Artistic Evolution

Winning the Prix de Rome allowed Girodet to travel to Italy, the essential destination for any aspiring history painter. He arrived in Rome in 1790, immersing himself in the study of classical antiquity and the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods. While the influence of classical sculpture remained paramount, Girodet was particularly drawn to the works of artists like Correggio and Leonardo da Vinci, admiring their subtle modeling, sfumato techniques, and psychological depth.

His time in Italy was transformative. Away from the direct supervision of David, Girodet began to cultivate a more personal style. This is most evident in the painting that secured his fame: The Sleep of Endymion (Le Sommeil d'Endymion), completed in 1791 and sent back to Paris for exhibition at the Salon of 1793. The painting depicts the beautiful shepherd Endymion cast in perpetual sleep by the moon goddess Selene (Diana), who loved him.

While the subject is classical, Girodet's treatment is revolutionary. The figure of Endymion is rendered with an almost ethereal softness, bathed in a cool, silvery moonlight that seems to emanate from an unseen source (symbolizing the goddess's kiss). The sensuous languor of the pose, the dreamlike atmosphere, and the innovative, almost mysterious lighting effects marked a significant departure from the heroic austerity often favored by David. The painting was a sensation, admired for its originality and poetic beauty, establishing Girodet as a major new talent with a unique voice.

Girodet's stay in Italy was not without peril. The French Revolution unfolding back home had repercussions abroad. Anti-French sentiment grew in Rome, particularly after the execution of Louis XVI. In 1793, riots erupted, and the French Academy was attacked. Girodet, along with other French artists, found himself in danger. According to accounts, he narrowly escaped harm, possibly aided by someone whose portrait he had painted. This experience of political turmoil and personal danger likely deepened his sensitivity to the dramatic and often chaotic aspects of human existence, themes that would surface in his later work. He subsequently traveled to Naples, Venice, and Genoa before finally returning to France in 1795.

Return to Revolutionary France and Artistic Independence

Girodet returned to a France profoundly changed by the Revolution. The Reign of Terror had passed, and the Directory was in power, but instability remained. The art world itself was undergoing transformation, with the old Academic system dismantled and the Salons opened to a wider range of artists. David, having been deeply involved in revolutionary politics and briefly imprisoned after Robespierre's fall, was re-establishing his position, but his absolute dominance was beginning to be challenged.

Girodet quickly re-established himself in Paris. While still respected as a former pupil of David, he increasingly asserted his artistic independence. His work continued to explore themes and stylistic avenues that diverged from strict Neoclassicism. He became known for his portraits, which often captured the sitter's personality with psychological acuity, as well as for history paintings that emphasized emotion and atmosphere.

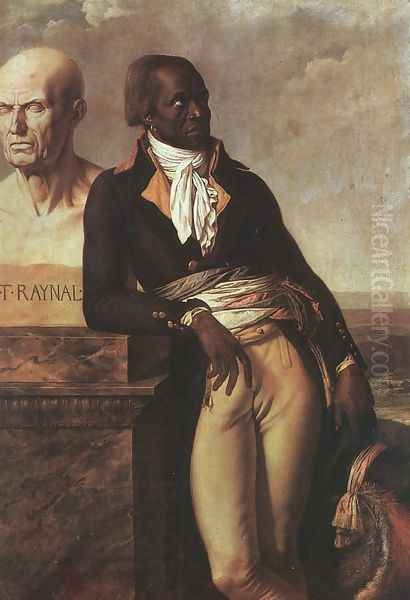

A notable work from this period is the Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley (c. 1797). Belley was a former slave from Saint-Domingue (Haiti) who became a representative to the National Convention in Paris and played a role in the abolition of slavery in 1794. Girodet depicts Belley leaning against a bust of the abolitionist philosopher Guillaume-Thomas Raynal. The portrait is remarkable for its dignified portrayal of a black subject, its political resonance in the context of revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality, and its sophisticated composition. It highlights Girodet's engagement with contemporary issues and figures.

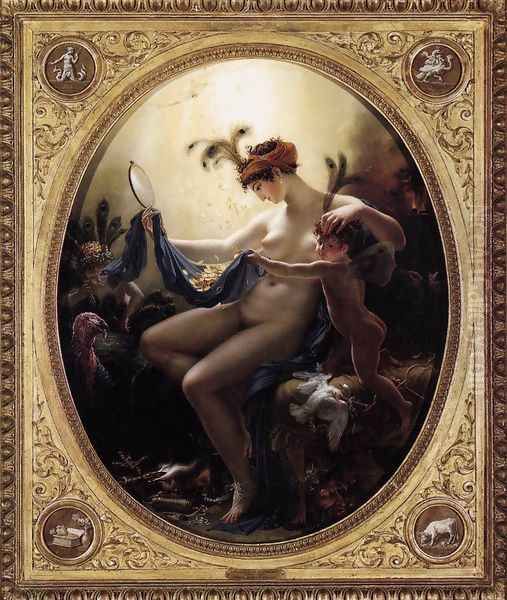

Another work that caused considerable stir was Mademoiselle Lange as Danaë (1799). This satirical portrait depicted a famous actress and courtesan, Anne Françoise Elisabeth Lange, who had apparently displeased Girodet after commissioning a more conventional portrait. He painted her as Danaë, visited not by Jupiter as a shower of gold, but by a shower of gold coins collected by a turkey (a pun on her lover's name) with the help of doves, while her child examines a peacock feather (symbolizing vanity). The painting, filled with witty and biting symbolism, was a succès de scandale, showcasing Girodet's sharp intellect and willingness to court controversy, further distancing him from the moral seriousness of Davidian Neoclassicism.

The Napoleonic Era: Major Commissions and Romantic Themes

With the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, first as Consul and then as Emperor, a new era of patronage began. Napoleon and his regime understood the power of art for propaganda and prestige, commissioning numerous works to glorify French achievements and the Emperor himself. Girodet, like many artists of his generation, including Gros and Gérard, benefited from this patronage, although his relationship with the regime was perhaps less central than that of some others.

One of his most significant commissions was for Napoleon's Château de Malmaison: Ossian Receiving the Ghosts of the French Heroes (1801-1802). Napoleon had a fascination with the poems of Ossian, supposedly ancient Gaelic epics (later revealed to be largely fabricated by James Macpherson). Girodet's painting depicts the blind bard Ossian welcoming the spirits of French generals who died in Napoleon's campaigns into a celestial Valhalla. The work is a quintessential example of early Romanticism: dreamlike, ethereal, filled with swirling figures, dramatic lighting, and a focus on myth, legend, and the supernatural. It stands in stark contrast to the rational clarity of Neoclassicism.

Another major work, The Deluge (Scène de déluge, exhibited 1806, completed later), further cemented Girodet's reputation for dramatic intensity. Depicting a family struggling desperately to survive a cataclysmic flood, the painting is a powerful image of human suffering and the overwhelming force of nature. It was seen by some as a direct challenge to David's Intervention of the Sabine Women, exhibited nearby. While David's work emphasized reconciliation and civic virtue, Girodet's focused on raw emotion, chaos, and tragedy, highlighting the shift towards Romantic sensibilities. The painting won a major prize in 1810, controversially surpassing David's entry.

Perhaps Girodet's most famous work exploring Romantic themes derived from contemporary literature is The Entombment of Atala (L'Enterrement d'Atala), exhibited at the Salon of 1808. Based on François-René de Chateaubriand's immensely popular novella Atala, the painting depicts the burial of the Christian Native American heroine Atala in the American wilderness, mourned by her lover Chactas and the hermit Father Aubry. The exotic setting, the tragic love story, the emphasis on religious piety and intense emotion, and the dramatic chiaroscuro lighting made it a landmark of French Romantic painting. It perfectly captured the era's fascination with exoticism, melancholy, and the fusion of love and death.

Girodet also undertook official commissions, such as The Revolt of Cairo (1810) and Napoleon Receiving the Keys of Vienna (1808, though sometimes mistakenly titled or confused with other events). While competent, these works perhaps show less of his distinctive personal style than his mythological or literary subjects. He remained highly regarded as a portraitist throughout this period, capturing likenesses of members of the Bonaparte family and other prominent figures.

Artistic Style: Precision and Poetry

Girodet's style is fascinating for its synthesis of seemingly opposing tendencies. From his training with David, he retained a commitment to precise drawing, anatomical accuracy, and carefully finished surfaces. His figures often have a sculptural quality, clearly defined and meticulously rendered. Unlike some later Romantics who favored looser brushwork, Girodet maintained a high degree of technical polish throughout his career.

However, he infused this Neoclassical foundation with elements that were distinctly proto-Romantic. His use of light was particularly innovative. He moved beyond the clear, even illumination often found in David's work, exploring dramatic chiaroscuro, mysterious glows, and subtle atmospheric effects, as seen brilliantly in Endymion and Atala. Light in Girodet's paintings often carries symbolic or emotional weight, creating mood and focusing attention.

His choice of subjects also signaled a shift. While he painted historical scenes, he was increasingly drawn to mythology, literature (especially contemporary works like Chateaubriand's), and themes that allowed for the exploration of sensuality, melancholy, the exotic, and the supernatural. Even when treating classical myths like Endymion or Danaë, he imbued them with a psychological complexity and often an erotic charge that felt new and sometimes unsettling to contemporary audiences.

His compositions could be complex and dynamic, sometimes deliberately ambiguous or unsettling, departing from the stable, frieze-like arrangements often favored in Neoclassicism. The Deluge is a prime example of a composition built on diagonals and turmoil, designed to evoke chaos and desperation. His color palette could range from the cool, silvery tones of Endymion to the richer, more dramatic hues of Atala or Ossian. He was a sophisticated colorist, using color to enhance mood and narrative.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Girodet's career unfolded alongside a generation of highly talented artists, many of whom were also products of David's studio. His relationship with his former master, Jacques-Louis David, evolved from that of a star pupil to a respectful but independent rival. While David reportedly admired Girodet's talent, he may have been perplexed or even critical of his stylistic departures, particularly the sensuality and perceived lack of moral clarity in works like Endymion. The competition between Girodet's Deluge and David's Sabines in 1810 highlighted their differing artistic paths.

With Antoine-Jean Gros, another prominent David student, Girodet shared the experience of navigating the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, particularly under Napoleonic patronage. However, their artistic temperaments differed. Gros excelled in large-scale, dynamic depictions of Napoleonic battles and contemporary events, often with a proto-Romantic flair for drama and color. Girodet's Romanticism was generally more introspective, literary, and focused on psychological states or mythological fantasy.

François Gérard, another fellow student, achieved great success as a portraitist and painter of elegant historical scenes, often seen as finding a smoother synthesis of Neoclassical grace and contemporary taste than the more idiosyncratic Girodet. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who revered classical ideals and precise linearity even more than David, represented a different path, becoming a rival to the more overtly Romantic painters like Delacroix later on. Girodet's work, with its blend of precision and poetic strangeness, occupied a unique space between the camps. He also interacted with figures like Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, another influential painter and teacher whose work bridged Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

Later Life, Legacy, and Influence

After the fall of Napoleon and the Bourbon Restoration in 1815, Girodet's artistic production slowed. He had inherited a significant fortune from Dr. Trioson, providing him with financial independence. His health, reportedly undermined by years of demanding work and perhaps lifestyle issues (some sources mention excessive drinking), began to decline. He increasingly turned his attention to literary pursuits, writing poetry (including a long didactic poem on painting) and creating illustrations for classic authors like Virgil, Racine, and Anacreon.

Despite painting less, he remained a respected figure in the art establishment. He was a member of the Institut de France and the Académie des Beaux-Arts (which replaced the old Académie Royale) and was made a Chevalier of the Order of Saint Michael. He also took on students, although his workshop never achieved the scale or influence of David's or Guérin's. Among those documented as his pupils or influenced by him were Hyacinthe Aubry-Lecomte, François-Édouard Bertin, Henri Decaisne, Alexandre-Marie Colin, Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie, and potentially others who passed through his circle.

Girodet died in Paris in 1824 at the age of 57. His legacy is that of a highly original artist who played a crucial role in the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. His emphasis on individual sensibility, emotional intensity, imaginative subjects, and innovative use of light anticipated key aspects of the Romantic movement that would fully emerge with artists like Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix in the 1820s.

While perhaps overshadowed at times by his teacher David or the more overtly Romantic Delacroix, Girodet's work has received renewed scholarly and public attention since the late 20th century. Major exhibitions, such as the one titled "Girodet: Romantic Rebel" held in Chicago, New York, and Montreal in 2006-2007, have highlighted his unique contribution to French art. His paintings, particularly The Sleep of Endymion and The Entombment of Atala, remain iconic images of the period, admired for their technical mastery and haunting, poetic beauty.

Conclusion

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Triosson was more than just a student of David; he was an innovator who forged his own path during a period of immense artistic and political change. He absorbed the lessons of Neoclassicism but infused them with a personal vision characterized by sensuality, psychological depth, and a fascination with the mysterious and the dramatic. His work bridges the rationalism of the Enlightenment with the emotionalism of the Romantic era, creating a unique and often captivating artistic language. From the ethereal beauty of Endymion to the tragic pathos of Atala, Girodet left behind a body of work that continues to speak to the complexities of the human condition, securing his place as a key figure in the evolution of modern European art.