Boris Dmitrievich Grigoriev stands as a significant, albeit complex, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Russian art. A master draftsman, a vibrant colorist, and a keen observer of humanity, his work traversed the tumultuous decades of revolution and exile, capturing the essence of the Russian spirit while simultaneously engaging with broader European artistic currents. Primarily known as a painter and graphic artist, Grigoriev was also a writer, adding another layer to his multifaceted creative output. His life journey, from provincial Russia to the art capitals of Europe and eventual settlement in France, mirrors the dislocations and cultural cross-pollination experienced by many Russian intellectuals and artists of his generation.

Grigoriev's art is often characterized by its expressive intensity, its focus on portraiture and the human figure, and its distinctive linear style. He navigated various stylistic influences, from Symbolism and Art Nouveau through to Expressionism and Neoclassicism, yet always maintained a unique, recognizable hand. His legacy is tied intrinsically to his powerful depictions of Russian peasant life, particularly the monumental Raseya cycle, but extends to encompass sensitive portraits, evocative landscapes, theatrical designs, and explorations of diverse cultural themes encountered during his extensive travels.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Boris Grigoriev was born in Moscow on July 11 (Old Style) / July 23 (New Style), 1886. His origins were somewhat unconventional; he was the illegitimate son of Dmitry Grigoriev, a banker. He spent his early childhood not in the bustling capital, but in the Volga River town of Rybinsk, where his adoptive parents raised him. His adoptive father was a bank employee who eventually rose to become a manager, while his mother, reportedly from a noble background, instilled in him an appreciation for music and literature. This mix of provincial life and cultural aspiration likely shaped his later artistic sensibilities.

His formal artistic training began in 1903 when he enrolled at the prestigious Stroganov Central School of Technical Drawing in Moscow. This institution provided a solid foundation in draftsmanship and applied arts. Seeking further development, Grigoriev moved to St. Petersburg in 1907 and entered the Imperial Academy of Arts. He studied there until 1912, though he reportedly did not formally graduate. His time at the Academy was crucial, placing him within the vibrant artistic milieu of the Silver Age.

At the Academy, he studied under notable professors, including Dmitry Kardovsky, a respected painter and teacher known for his emphasis on precise drawing and composition. While formal instruction provided technique, Grigoriev was also absorbing the dynamic atmosphere of St. Petersburg's art world. He was exposed to the latest European trends – French Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the burgeoning avant-garde movements – alongside the powerful traditions of Russian realism, exemplified by figures like Ilya Repin, and the stylized elegance of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement.

The Mir Iskusstva Connection

Grigoriev's association with the influential Mir Iskusstva group began around 1909, and he became a formal member in subsequent years. Founded by figures like Alexandre Benois, Konstantin Somov, Léon Bakst, and the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, Mir Iskusstva championed artistic synthesis, aestheticism, and a retrospective appreciation for 18th-century Russian and Western European art, while also embracing Symbolism and Art Nouveau. They were pivotal in promoting Russian art and culture abroad, particularly through Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.

Membership in Mir Iskusstva provided Grigoriev with exhibition opportunities and connected him with leading artists, writers, and intellectuals. He participated in their exhibitions, contributing works that aligned with the group's sophisticated aesthetic while retaining his own burgeoning style. His involvement wasn't limited to painting; Grigoriev was also drawn to literature and contributed writings, reflecting the group's interest in the integration of various art forms. This period solidified his reputation within the Russian art scene.

He also became associated with other avant-garde circles, exhibiting with the progressive "Union of Youth" group, which included radical artists like Kazimir Malevich, Mikhail Larionov, and Natalia Goncharova. Though Grigoriev never fully embraced the non-objective art of Suprematism or Rayonism, his participation indicates his engagement with the experimental spirit of the time. He absorbed elements from various movements, including Cubism and Fauvism, integrating them into his fundamentally figurative but highly expressive style.

Capturing the Russian Spirit: The Pre-Revolutionary Period

During the years leading up to the 1917 Revolution, Grigoriev established himself as a distinctive voice in Russian art. His work from this period often focused on Russian themes, particularly the lives and characters of the peasantry and provincial town dwellers. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture the psychological essence of his subjects, often exaggerating features or using stark linearity to convey inner turmoil, resilience, or a kind of primal earthiness.

His portraits from this era are notable for their intensity. He painted fellow artists, writers, and intellectuals, often employing a sharp, almost graphic style. His line work was becoming a defining characteristic – precise, energetic, and descriptive. Color was used expressively rather than purely naturalistically, contributing to the emotional impact of the works. He travelled within Russia, observing and sketching the diverse faces and landscapes of his homeland.

Works like Before the Storm (1913) showcase his ability to imbue scenes with symbolic weight and atmospheric tension. His illustrations for children's books and literary works also gained recognition, demonstrating his versatility and his connection to the rich tradition of Russian graphic arts. He was fascinated by folklore and the grotesque, elements that surfaced in works like Visiting Baba Yaga (1911), drawing inspiration from both traditional tales and the literary worlds of Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

The Raseya Cycle: A Monumental Vision

Arguably Grigoriev's most famous and ambitious project from his Russian period is the Raseya (Faces of Russia) series, created primarily between 1916 and 1918. This cycle of paintings and drawings aimed to encapsulate the soul of rural Russia, depicting the peasants – men, women, and children – with an unflinching, often harsh, yet deeply empathetic gaze. These were not idealized pastoral figures but weathered, enduring individuals shaped by the land and their often difficult lives.

The Raseya figures are rendered with Grigoriev's characteristic sharp linearity and expressive distortion. Faces are often mask-like, emphasizing archetypal qualities over individual portraiture. The colors can be earthy and somber, or surprisingly vibrant, highlighting the raw vitality beneath the surface poverty. Grigoriev sought to convey the deep-seated strength, piety, and perhaps the perceived backwardness and mystery of the Russian peasantry – the bedrock of the nation.

The series was exhibited to considerable acclaim in St. Petersburg (then Petrograd) in 1918, coinciding with the immense social upheaval following the Bolshevik Revolution. Initially, the works were interpreted by some, including the influential critic Alexandre Benois, as a profound and timely exploration of the Russian national character. They seemed to resonate with the revolutionary search for authentic Russian identity rooted in the common people.

Style and Technique: A Unique Visual Language

Boris Grigoriev's artistic style is difficult to categorize neatly within a single movement, which speaks to his independent spirit. However, several key characteristics define his work. Expressionism is perhaps the most fitting broad label, particularly in his emphasis on subjective experience, emotional intensity, and the distortion of form for expressive effect. His connection to German Expressionism is evident, though his work retains a distinctly Russian flavor.

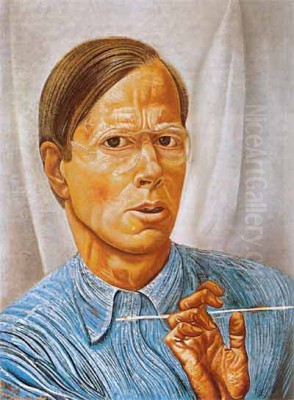

Line is paramount in Grigoriev's art. His draftsmanship is exceptional – confident, incisive, and highly descriptive. Whether in quick sketches or finished paintings, the linear structure often dominates, defining forms and conveying energy. This linearity sometimes lends his work a graphic quality, linking it to traditions of illustration and printmaking. He was a master of conveying character and form through line alone.

His use of color is equally distinctive. While capable of subtle harmonies, he often employed bold, sometimes dissonant color combinations to heighten the emotional impact. Influences from Fauvism, particularly the work of Henri Matisse, can be seen in his non-naturalistic application of color. Yet, his palette also draws from Russian folk art (lubok) and icon painting, with their traditions of strong outlines and flat areas of vibrant color.

Grigoriev excelled in portraiture. His subjects ranged from anonymous peasants to famous cultural figures like the poet Anna Akhmatova or the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold. In each case, he sought to penetrate beyond mere likeness to reveal the inner life or psychological state of the sitter. His portraits are often unsettling, confronting the viewer with their direct gaze and expressive intensity.

His versatility extended beyond painting and drawing. He was an accomplished illustrator, bringing his unique style to literary works. He also created designs for the theatre, notably collaborating with the innovative director Vsevolod Meyerhold, producing work that reflected Meyerhold's own anti-realistic, biomechanical theories through grotesque and dynamic imagery. Grigoriev also wrote prose and poetry, further demonstrating the breadth of his creative interests.

Revolution, Controversy, and Emigration

The Russian Revolution of 1917 profoundly impacted Grigoriev's life and career. While initially his Raseya series seemed aligned with the revolutionary spirit's focus on the peasantry, the political climate soon shifted. The very qualities that made the series powerful – its raw depiction of poverty, its sometimes grotesque figures, its ambiguous psychological depth – began to be viewed with suspicion by the increasingly rigid Soviet cultural authorities.

The interpretation of Raseya shifted. What was once seen as an exploration of the national soul came to be perceived by some officials as a pessimistic or even satirical portrayal of the very people the revolution claimed to liberate. The perceived ambiguity and lack of clear ideological affirmation made the works problematic. Grigoriev, whose art was fundamentally rooted in personal vision rather than political doctrine, found himself increasingly out of step with the demands for Socialist Realism.

Facing political pressure and artistic constraints, Grigoriev made the difficult decision to leave Russia. In 1919, he managed to cross the Gulf of Finland by boat, reaching Berlin. This marked the beginning of his life as an émigré artist. His departure was part of a larger exodus of Russian intellectuals and artists who felt alienated or threatened by the new regime, including figures like Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall (though he later returned briefly), Ivan Bunin, and many others associated with the pre-revolutionary cultural elite.

In the Soviet Union, Grigoriev's work, particularly the Raseya cycle, fell out of favor. Many of his paintings were removed from public display in museums and relegated to storage archives (spetsfond), effectively erasing him from the official narrative of Soviet art history for decades. His name became associated with the "bourgeois" art of the past and the perceived betrayal of emigration.

Life and Work in Exile: France and Beyond

After leaving Russia, Grigoriev spent time in Berlin and Paris, centers for the Russian émigré community. Paris, in particular, was a hub of artistic activity, and he reconnected with fellow Russian artists while also engaging with the French art scene. He continued to paint portraits, often depicting fellow émigrés, capturing the sense of displacement and nostalgia that marked their lives. His style remained distinctive, though perhaps tempered slightly by his new environment.

He traveled extensively during the 1920s and 1930s. He visited Brittany in northwestern France frequently, captivated by the rugged coastal landscapes and the traditional lives of the Breton fishermen and peasants. This resulted in a significant body of work, including paintings like Binious (The Piper), which depicted local musicians. These Breton scenes, while different in subject matter, share an affinity with his earlier Russian peasant themes – an interest in authentic, rooted folk culture.

Grigoriev achieved considerable international recognition during his exile. He exhibited successfully in Paris, London, New York, Chicago, and other cities. His work was sought after by collectors, particularly in the United States. He undertook trips to North and South America in the late 1920s and 1930s, lecturing and exhibiting. These travels further broadened his horizons and resulted in works reflecting his experiences, such as the Visages du Monde (Faces of the World) series.

In 1927, Grigoriev settled permanently in the south of France, in Cagnes-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, a town popular with artists (Renoir had spent his last years there). He built a villa he named "Borisella," which became his home and studio for the remainder of his life. Here, he continued to paint portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes inspired by the Mediterranean light and local life.

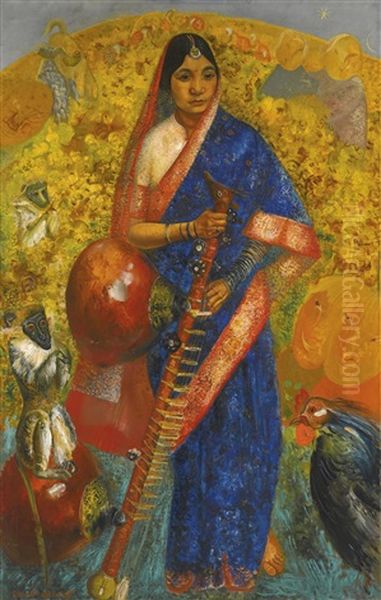

One notable work from his later period is the large-scale painting Ramayana (1931), inspired by the Indian epic. This piece, depicting the goddess Sita, showcases his enduring interest in diverse cultural themes and his mastery of complex compositions and vibrant color. While seemingly distant from his Russian roots, it perhaps reflects a universalizing tendency in his later work, exploring grand human narratives.

Connections and Artistic Milieu

Throughout his career, both in Russia and in exile, Grigoriev maintained connections within the artistic community. His early involvement with Mir Iskusstva linked him to Benois, Somov, Bakst, and Diaghilev. His participation in avant-garde exhibitions connected him, however briefly, with Malevich, Larionov, and Goncharova. His teaching connection was primarily through Kardovsky at the Academy.

In exile, he was part of the vibrant Russian émigré cultural scene in Paris and Berlin. He painted portraits of prominent figures within this community. His theatrical work connected him with the visionary director Vsevolod Meyerhold, a collaboration that highlights Grigoriev's ability to adapt his style to different mediums and artistic visions.

His work shows an awareness of broader European trends. Echoes of French masters like Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and especially Henri Matisse can be discerned in his handling of color and line, though always filtered through his unique sensibility. He absorbed lessons from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, integrating them into a style that remained recognizably his own. He was a contemporary of other major Russian émigré artists like Marc Chagall and Chaim Soutine, though his artistic path diverged significantly from theirs. He also shared the artistic landscape with unique Russian figures who remained, like Pavel Filonov, whose intense, detailed style offers a fascinating counterpoint.

Personal Life and Character

Accounts suggest Grigoriev possessed a complex and perhaps difficult personality. Descriptions sometimes mention a certain arrogance or flamboyance, possibly cultivated as part of an artistic persona. His "disorderly" upbringing, as mentioned in some sources (though details about his early life vary), might have contributed to a restless energy evident in his life and work.

His personal life included marriage and family. He married Elena Grigorieva (née Klara von Lindenberg) and they had a son, Kirill. Like many artists, he likely faced financial pressures and the challenges of balancing creative pursuits with family responsibilities, particularly during the tumultuous years of revolution and emigration. Anecdotes, such as a supposed early marriage to a different woman named Klara ending due to these pressures, hint at personal struggles beneath the surface of his professional success. His move to Cagnes-sur-Mer and the building of "Borisella" suggest a desire for stability in his later years.

Legacy and Conclusion

Boris Grigoriev died in Cagnes-sur-Mer on February 7, 1939, shortly before the outbreak of World War II. He left behind a substantial and diverse body of work that secures his place as a major figure in 20th-century Russian art. His legacy is multifaceted: he was a brilliant draftsman, an expressive colorist, a penetrating portraitist, and a chronicler of the Russian soul during a period of profound transformation.

His Raseya cycle remains a landmark achievement, offering an unforgettable vision of pre-revolutionary rural Russia. While controversial in its time and suppressed for decades in the Soviet Union, it is now recognized as a powerful and complex artistic statement. His work in exile demonstrates his adaptability and his continued engagement with the human condition, albeit in different cultural contexts.

Grigoriev's art bridges the gap between the traditions of Russian realism and the innovations of European modernism. He absorbed influences from various sources but forged a highly personal style characterized by its linear energy and psychological intensity. His work continues to fascinate viewers with its technical mastery and its often unsettling exploration of character and identity. Long overshadowed in his homeland due to political circumstances, Grigoriev's art has experienced a resurgence of interest in post-Soviet Russia and maintains a significant presence in collections and art historical discourse worldwide. He remains a testament to the enduring power of individual artistic vision, even amidst the storms of history.