Anselm Friedrich Feuerbach stands as a significant, albeit sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of 19th-century German art. Born into a family renowned for intellectual pursuits, he navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, forging a unique path that blended the rigour of Classicism with the burgeoning emotionalism of Romanticism. His life and work reflect a deep engagement with the past, a quest for ideal beauty, and a personal struggle for recognition that shaped his artistic journey and legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

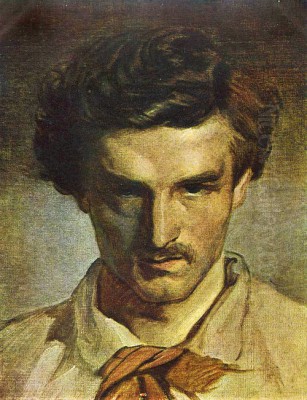

Anselm Feuerbach was born on September 12, 1829, in Speyer, Germany. His lineage was distinguished; he was the grandson of the influential legal scholar Paul Johann Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach, the son of the archaeologist Joseph Anselm Feuerbach, and the nephew of the philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach. This intellectual environment undoubtedly fostered a sensitivity to history, philosophy, and the classical world that would permeate his later artistic endeavours.

His formal artistic training began at the Düsseldorf Academy, a major centre for German painting, particularly known for its history painting and landscape traditions under figures like Wilhelm von Schadow and Carl Friedrich Lessing. Seeking broader horizons, Feuerbach continued his studies in Munich and later in Antwerp, absorbing the different artistic approaches prevalent in these cities. A pivotal moment came in 1851 when he moved to Paris, the vibrant heart of the European art world.

In Paris, Feuerbach encountered the powerful realism of Gustave Courbet and the lyrical landscapes of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. He also studied briefly in the studio of Thomas Couture, known for his large-scale historical compositions. These encounters exposed him to contemporary French art trends, influencing his technique and broadening his artistic perspective beyond the German academic tradition. It was also during this period that his engagement with classical themes began to solidify, tempered by the realities and sensibilities of modern French painting.

The Roman Years and Artistic Maturity

Like many artists of his generation drawn to the classical past, Feuerbach found immense inspiration in Italy. He spent significant periods in Rome, starting from the mid-1850s. Italy, particularly Rome, became his spiritual and artistic home. The ruins of antiquity, the masterpieces of the Renaissance, and the vibrant light and landscape of the Italian peninsula deeply affected his artistic vision.

His time in Rome was crucial for developing his mature style and establishing important connections. He became associated with the "Deutschrömer" (German Romans), a circle of German-speaking artists living and working in the city. Among his closest associates were Arnold Böcklin, known for his symbolist and mythological paintings, and Hans von Marées, another key figure in German idealism. Through them, Feuerbach met the influential art collector and patron Count Adolf von Schack in 1862. Schack became an important supporter, commissioning Feuerbach to paint copies of Italian Renaissance masterpieces, which further deepened his understanding of the Old Masters.

Rome was also where Feuerbach encountered the women who would become central figures in his art and life. In 1861, he met Anna Risi, affectionately known as "Nanna." A working-class Roman woman of striking beauty, she became his primary model for several years and the subject of numerous portraits, including the famous Nanna (1861). Their relationship was intense and complex, a source of both inspiration and emotional turmoil for the artist. Nanna embodied Feuerbach's ideal of classical beauty fused with a sense of melancholic dignity.

Later, after Nanna left him, Feuerbach formed a relationship with Lucia Brunacci, who also served as his model and mistress. She notably posed for his monumental painting Medea (1870). These relationships highlight the intertwining of Feuerbach's personal life and artistic creation, with his models often embodying the idealized, yet emotionally resonant, figures that populate his canvases.

Style and Technique: The Classical Ideal Reimagined

Feuerbach's artistic style is best characterized as a synthesis of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. He revered the formal harmony, idealized beauty, and noble subjects of Greek and Roman antiquity, as well as the High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Titian. However, he infused these classical forms with a distinctly 19th-century sensibility, marked by introspection, melancholy, and a focus on psychological depth.

His technique was meticulous and deliberate. He built up his paintings with careful drawing and layered application of paint, often favouring a somewhat muted, tonal palette. Critics sometimes pointed to a lack of vibrant colour or a certain "fogginess" in his work, suggesting his intense focus on form and idealization occasionally came at the expense of painterly immediacy. However, his handling of light and shadow could be exceptionally subtle, creating a poetic, often elegiac mood that became a hallmark of his style.

Feuerbach possessed a profound understanding of human anatomy and was skilled in rendering the human form with classical grace and solidity. His figures often possess a sculptural quality, appearing statuesque and serene, yet imbued with an underlying emotional weight. This is particularly evident in his depictions of idealized female figures drawn from mythology or history, such as Iphigenia or Medea.

He believed strongly in the connection between technical mastery and artistic expression. For Feuerbach, refined craftsmanship was not merely an end in itself but the necessary vehicle for conveying profound ideas and emotions. He felt that imperfect technique, particularly in the handling of colour, could compromise the highest aspirations of art. This conviction drove his painstaking approach but perhaps also contributed to a certain academic restraint that set him apart from more radical contemporaries.

Major Themes: Mythology, History, and Philosophy

Feuerbach's choice of subject matter reflects his deep immersion in classical culture and literature. Greek mythology provided a rich source of inspiration, allowing him to explore universal human emotions and archetypal narratives through figures like Iphigenia, Medea, Orpheus, and the Amazons. He approached these myths not merely as illustrations but as vehicles for exploring themes of fate, sacrifice, love, loss, and the tragic dimensions of human existence.

His Iphigenia paintings, for example, depict the priestess in exile, gazing longingly across the sea towards her homeland. These works convey a profound sense of melancholy, solitude, and yearning, transforming the mythological figure into an emblem of Romantic introspection. Similarly, his depictions of Medea, particularly Medea's Farewell, capture the intense emotional conflict of the sorceress, referencing classical forms while emphasizing psychological drama.

History and literature also featured prominently. His Dante in Ravenna portrays the exiled poet contemplating his fate, surrounded by noble figures, evoking a sense of historical grandeur and intellectual weight. One of his most ambitious projects was The Banquet of Plato (also known as The Symposium), which he painted in two versions. These large-scale compositions depict the famous philosophical gathering described by Plato, aiming to capture the intellectual ferment and idealized camaraderie of ancient Greek philosophy.

Feuerbach's works often carry a philosophical weight, reflecting his family background and his own contemplative nature. Paintings like The Sea, featuring a solitary female figure in classical drapery contemplating the vast ocean, transcend specific narrative to evoke broader themes of nature, beauty, and the human condition. He sought to create art that was not only beautiful but also intellectually and emotionally resonant, embodying a high-minded ideal often associated with German idealism.

Key Masterpieces

Several works stand out as defining examples of Feuerbach's artistic achievement and encapsulate his core concerns:

Hafiz at the Fountain (1852, second version 1866): An early success, this painting depicts the Persian poet Hafiz in a moment of reverie. It combines exotic subject matter with a lyrical, almost musical composition and demonstrates Feuerbach's skill in creating atmospheric scenes imbued with poetic feeling. The work reflects the influence of Romantic Orientalism but is rendered with Feuerbach's characteristic classical restraint.

Nanna (1861): This portrait of Anna Risi is one of Feuerbach's most iconic images. It presents Nanna with a dignified, almost regal bearing, her dark features set against a simple background. The painting captures both her striking beauty and a sense of profound melancholy, embodying the artist's ideal of classical form infused with inner life. It showcases his mastery of portraiture and his ability to convey psychological depth.

Iphigenia (multiple versions, e.g., 1862, 1871): These paintings are perhaps the most quintessential expressions of Feuerbach's style. Depicting the exiled priestess yearning for Greece, they are studies in solitude and longing. The figure of Iphigenia, draped in classical robes and set against a vast seascape, becomes a powerful symbol of Romantic melancholy and the idealization of the classical past.

Medea (1870): This large canvas depicts Medea preparing for her departure after being spurned by Jason. Feuerbach captures the moment of intense emotional turmoil, focusing on Medea's stern resolve and the sorrow of her attendants. The composition draws inspiration from Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael, but the psychological intensity is characteristic of Feuerbach's approach to mythological subjects. Lucia Brunacci served as the model for Medea.

The Battle of the Amazons (1870-1873): One of Feuerbach's most monumental works, this vast canvas depicts the mythical conflict with dynamic energy and classical heroism. Measuring over four by nearly seven meters, it was an ambitious undertaking intended for a public space. While showcasing his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions in the grand manner of history painting, its reception was mixed.

The Banquet of Plato (First version 1869, Second version 1871-1874): These ambitious paintings attempt to visualize Plato's dialogue, depicting Socrates and other philosophers engaged in discussion. Feuerbach sought to convey the intellectual atmosphere and idealized male fellowship of ancient Athens. The second version, now in Vienna, is considered the more successful, demonstrating his commitment to philosophical and historical themes on a grand scale.

Contemporaries and Connections

Feuerbach's artistic journey unfolded within a rich network of relationships with fellow artists, patrons, and critics. His interactions reveal both camaraderie and conflict, shedding light on his personality and position within the 19th-century art world.

His close association with Arnold Böcklin and Hans von Marées in Rome was formative. Together, they represented a strand of German art focused on idealism and classical renewal, distinct from the growing trends of Realism and Impressionism. While their paths eventually diverged, and Feuerbach's friendship with Böcklin reportedly ended due to personal friction, their shared time in Italy was significant. Feuerbach acknowledged Böcklin's talent, noting the "purposefulness" in his work.

The patronage of Count Adolf von Schack provided crucial financial support and validation, enabling Feuerbach to remain in Italy and focus on his ambitious projects. Schack's collection, now housed in the Schack Galerie in Munich, includes several important works by Feuerbach, Böcklin, and Marées.

Feuerbach's early influences included his teachers at the Düsseldorf Academy, such as Wilhelm von Schadow, and prominent figures of the school like Carl Friedrich Lessing. In Munich, he would have been aware of the historical paintings of Karl von Piloty. His time in Paris brought him into contact with the orbits of Gustave Courbet, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Thomas Couture, whose differing approaches broadened his artistic vocabulary.

He also played a role in encouraging younger artists. Wilhelm Trübner, who later became associated with the Leibl Circle and German Realism, met Feuerbach in 1867 and was reportedly encouraged by him to pursue painting.

However, not all interactions were harmonious. His later years were marked by a perceived rivalry with the younger, immensely popular Viennese painter Hans Makart. When Feuerbach accepted a professorship at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in 1873, Makart was the reigning star of the city's art scene, known for his opulent, theatrical style. The contrast between Feuerbach's severe classicism and Makart's flamboyant historicism was stark, and Feuerbach felt overshadowed and unappreciated, contributing to his decision to resign after only a year.

While direct records might be scarce, he likely moved in the same broader circles as other prominent German artists of the era, such as the leading portraitist Franz von Lenbach, who also enjoyed the patronage of figures like Count von Schack.

Challenges, Reception, and Controversy

Despite his talent and dedication, Feuerbach's career was marked by significant challenges and a lack of widespread contemporary acclaim. He struggled with financial difficulties throughout much of his life and faced personal hardships, including complex relationships and potential marital problems (though details remain limited in the provided sources).

His art, while admired by some connoisseurs like Count von Schack, often failed to find favour with the broader public or official institutions. His serious, often melancholic, classicism ran counter to the tastes of the Gründerzeit era in Germany and Austria, which often preferred more decorative, optimistic, or overtly nationalistic art. His monumental paintings, such as The Battle of the Amazons and the first version of The Banquet of Plato, received critical receptions that left him deeply disappointed and embittered.

Critics often found his work too severe, too intellectual, or lacking in visual appeal. Some pointed to technical limitations, suggesting that his execution did not always match the grandeur of his conceptions. The criticism that his colours could appear "foggy" or "flat" persisted. There was also the recurring observation that his works sometimes felt more "literary" than purely painterly, perhaps reflecting his deep engagement with texts and ideas but suggesting a perceived deficit in translating these into fully realized visual terms.

The rivalry with Hans Makart in Vienna exemplified the difficulties Feuerbach faced in gaining recognition. He felt misunderstood and undervalued, leading to his withdrawal from the professorship and increasing isolation. This sense of frustration and disillusionment coloured his later years.

Controversy also touched his legacy posthumously. During World War II, at least one of his works, Head of a Girl, was confiscated by the Nazis as part of their systematic looting of art, representing a tragic loss to his oeuvre and cultural heritage.

Later Years and Legacy

After resigning from the Vienna Academy in 1874, Feuerbach spent his remaining years primarily between Venice and Nuremberg. He continued to paint but lived in relative seclusion, increasingly withdrawn from the mainstream art world. His health declined, possibly exacerbated by years of struggle and disappointment. Anselm Feuerbach died of heart failure in Venice on January 4, 1880, at the age of 50.

His stepmother, Henriette Feuerbach, played a crucial role in preserving his memory. She collected his letters and writings, publishing them posthumously under the title Ein Vermächtnis (A Legacy) in 1882. This publication, containing his reflections on art and life, helped shape the understanding of Feuerbach as a sensitive, intellectual, and tragically misunderstood artist. While it revealed his literary aspirations, it also confirmed that some of his grander literary plans remained unfulfilled.

In the decades following his death, Feuerbach's reputation underwent a gradual re-evaluation. Art historians began to recognize his unique position as a bridge between Neoclassicism and the emerging currents of Symbolism and modern German art. He came to be seen, alongside Böcklin and Marées, as one of the leading figures of German Idealism in the later 19th century – artists who sought to imbue classical forms with profound psychological and philosophical meaning.

Today, Anselm Feuerbach is acknowledged as a major German painter of his era. His works are housed in prominent museums across Germany and Austria, including the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Neue Pinakothek and Schack Galerie in Munich, the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. While his art may lack the immediate appeal of some of his contemporaries, its intellectual depth, formal elegance, and melancholic beauty continue to resonate. He remains a testament to the enduring power of the classical tradition, reinterpreted through the lens of 19th-century introspection and feeling.

Conclusion

Anselm Feuerbach's life and art embody the complexities of a period of transition. Rooted in the classical tradition and inspired by the Italian Renaissance, he sought an art of ideal beauty and profound meaning. Yet, he infused his work with a Romantic sensibility, exploring themes of longing, melancholy, and psychological depth that spoke to the modern condition. His meticulous technique and dedication to high-minded subjects set him apart, but also contributed to the challenges he faced in achieving contemporary recognition.

Caught between the enduring legacy of Classicism and the emotional currents of Romanticism, Feuerbach forged a distinctive artistic identity. His struggles with patrons, critics, and rivals, combined with his intense personal relationships and unwavering commitment to his artistic vision, paint a picture of a dedicated, sensitive, yet often embattled artist. Though perhaps not as widely celebrated during his lifetime as he might have wished, Anselm Feuerbach's legacy endures as a significant contributor to 19th-century German art, an artist whose work continues to invite contemplation on beauty, history, and the human spirit.