Barthel Beham (1502-1540) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the constellation of German art during the Northern Renaissance. A contemporary of giants like Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger, Beham carved out a distinct niche for himself, primarily as a master engraver – one of the celebrated "Little Masters" – and later as a sought-after court portraitist. His life, though tragically short, was marked by artistic brilliance, intellectual ferment, and the profound socio-religious upheavals of the Reformation era. This exploration delves into Beham's biography, his artistic development, his key works, his connections within the vibrant artistic milieu of Nuremberg and Munich, and the enduring legacy of his contributions to German art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Nuremberg

Born in Nuremberg in 1502, Barthel Beham emerged from an environment steeped in artistic tradition. Nuremberg, at the turn of the 16th century, was a bustling imperial free city, a center of commerce, humanism, and artistic innovation. It was the city of Albrecht Dürer, whose towering influence permeated the artistic landscape. Barthel was the younger brother of Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550), who also became a prominent engraver and painter. The Beham brothers likely received their initial artistic training together, possibly within a family workshop or under a local master.

The pervasive influence of Albrecht Dürer on young artists in Nuremberg cannot be overstated. While direct documentary evidence of Barthel Beham formally apprenticing in Dürer's workshop is lacking, his earliest works, dating from around 1520, unmistakably bear the imprint of Dürer's graphic style. This is evident in the choice of subjects, the compositional arrangements, and the meticulous, confident line work characteristic of Dürer's engravings and woodcuts. Hans Sebald Beham is more clearly documented as having connections to Dürer's circle, and it is plausible that Barthel benefited from this association, either directly or indirectly.

Beyond Dürer, the artistic currents of the Italian Renaissance were beginning to flow northwards, often transmitted through prints. Engravings by Italian masters, particularly those by Marcantonio Raimondi who popularized Raphael's designs, were circulating in Germany. Barthel Beham, even in his early Nuremberg period, demonstrated an awareness of these classical themes and stylistic innovations. His early engravings often feature mythological subjects, such as his depictions of Cleopatra, which show an engagement with the idealized human form and narrative compositions derived from Italian models, albeit translated into a distinctly German visual language.

The "Godless Painters" Controversy and Exile

Barthel Beham's burgeoning career in Nuremberg took a dramatic turn in 1525. This period was one of intense religious and social turmoil, as the Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther, swept across German lands. Nuremberg itself was grappling with these changes, officially adopting Lutheranism in the same year. Amidst this charged atmosphere, Barthel Beham, his brother Hans Sebald, and fellow artist Georg Pencz (c. 1500-1550) found themselves at the center of a major controversy.

The three artists, who became known as the "godless painters" (gottlose Maler), were arrested and brought before the Nuremberg city council. They were accused of holding and propagating radical religious and political views that challenged the established order. Specifically, they were charged with denying the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist (transubstantiation), questioning the efficacy of baptism, and expressing skepticism about the authority of the civic and religious institutions. Some accounts suggest they also voiced support for the radical reformer Thomas Müntzer, a leader in the German Peasants' War (1524-1525), which was brutally suppressed.

Their views were deemed heretical and seditious. Despite their artistic talents, the council, keen to maintain order during a volatile period, expelled the three "godless painters" from Nuremberg in January 1525. This event was a significant disruption to their careers and personal lives. While Hans Sebald and Georg Pencz eventually managed to return to Nuremberg for periods, Barthel Beham's exile proved more permanent, redirecting the course of his artistic journey. The controversy highlights the dangerous intersection of art, religion, and politics during the Reformation, where artists were not immune to the ideological battles raging around them.

A New Chapter in Munich: Court Painter to the Bavarian Dukes

Following his expulsion from Nuremberg, Barthel Beham's path eventually led him to Munich, the capital of the staunchly Catholic Duchy of Bavaria. This move marked a significant shift in his patronage and, to some extent, his artistic focus. By the late 1520s, Beham had entered the service of the Bavarian Dukes, Wilhelm IV (1493-1550) and his co-ruling brother Ludwig X (1495-1545). This ducal patronage provided him with stability and new opportunities, particularly in the realm of portraiture.

Wilhelm IV was a significant patron of the arts, commissioning works from various German masters, including Albrecht Altdorfer and Ludwig Refinger, to adorn his residences and assert his cultural prestige. For Barthel Beham, the Munich court offered a different environment from the more burgher-centric art market of Nuremberg. As a court painter, his primary responsibility became the creation of portraits of the ducal family and prominent members of their court.

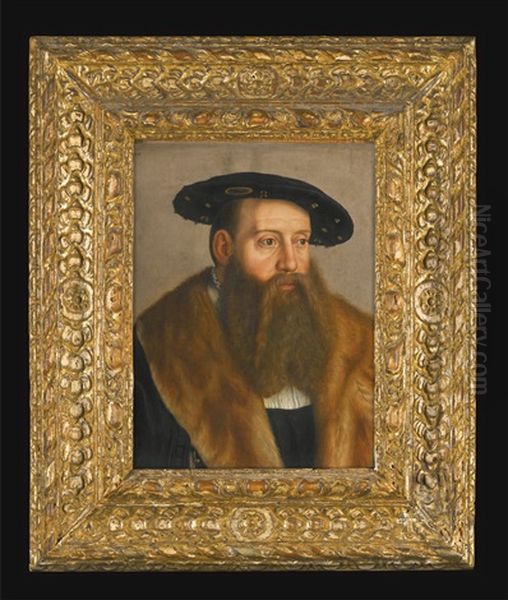

It is in Munich that Beham truly distinguished himself as a portrait painter of exceptional skill. His portraits are characterized by their psychological acuity, meticulous rendering of detail, and a sober, dignified presentation of the sitters. He moved away from the more generalized or idealized forms sometimes seen in earlier German portraiture, capturing the individual likeness and character of his subjects with remarkable precision. His technique, often on panel, involved smooth, almost enamel-like surfaces, with careful attention to textures of fabric, fur, and flesh. These portraits served not only as personal mementos but also as statements of status and power within the courtly context.

One of his most celebrated works from this period is the Portrait of Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1527), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Von Eck was a powerful and influential figure in the Bavarian court, and Beham’s portrayal captures his stern, intelligent, and somewhat formidable personality. The meticulous detail in the rendering of his fur-lined robe and the subtle modeling of his features demonstrate Beham's mastery. This work, and others like it, established Beham as one of the leading portraitists in Southern Germany, comparable in quality, if not in international fame, to his contemporary Hans Holbein the Younger, who was then active in Basel and later England.

The Influence of Italy and the Embrace of Mannerism

While serving the Bavarian Dukes, Barthel Beham is believed to have undertaken at least one journey to Italy, likely around 1530 or shortly thereafter. Such trips were becoming increasingly common for Northern European artists eager to study classical antiquity and the achievements of the Italian Renaissance firsthand. Dürer himself had made two influential journeys to Italy, and their impact on his art was profound.

Beham's Italian sojourn appears to have exposed him to the emerging style of Mannerism. This style, which developed in the wake of High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, was characterized by elongated figures, exaggerated poses (the figura serpentinata), complex and often crowded compositions, and a heightened sense of drama and emotional intensity. Artists like Giulio Romano (a pupil of Raphael, active in Mantua) and Parmigianino were key proponents of this new aesthetic.

The influence of Italian art, and specifically Mannerism, is discernible in Beham's later prints. His figures sometimes adopt more contorted and dynamic poses, and his compositions can display a greater complexity and artifice than his earlier, Dürer-influenced works. While his painted portraits largely retained a Northern sobriety, his graphic work provided a venue for exploring these new stylistic currents. This engagement with Italian Mannerism demonstrates Beham's continued artistic curiosity and his desire to integrate contemporary European trends into his own visual language. His death in Italy in 1540, during what may have been a subsequent visit or an extended stay, further underscores his connection to the Italian artistic scene.

Mastery of Engraving: Themes and Techniques

Throughout his career, even as he gained prominence as a portrait painter, Barthel Beham remained a prolific and highly skilled engraver. It is for his prints, particularly his small-format engravings, that he is grouped with his brother Hans Sebald, Georg Pencz, Heinrich Aldegrever, and others as one of the "Little Masters" (Kleinstenmeister). This term refers not to a diminutive talent, but to the characteristically small scale of their prints, which were highly detailed and technically sophisticated.

These small engravings were affordable and easily transportable, making them popular with a broad audience of collectors, from wealthy burghers to fellow artists. They served various purposes: as devotional images, illustrations of classical or biblical narratives, moral allegories, genre scenes, and even erotica. Beham excelled in this demanding medium. Engraving requires immense precision and control, as the artist incises lines directly onto a copper plate with a burin. The density and direction of these lines create tone, texture, and form.

Beham's engravings cover a wide range of subjects:

Religious Scenes: He produced traditional biblical subjects, but sometimes with a contemporary or critical edge, reflecting the theological debates of the Reformation. An example is Christ and the Sheepfold, which could be interpreted as a critique of ecclesiastical corruption.

Mythological and Classical Themes: Reflecting the humanist interests of the Renaissance, Beham frequently depicted scenes from Greek and Roman mythology, such as The Judgment of Paris, Leda and the Swan, and various exploits of Hercules. His Cleopatra engravings are notable for their sensuous portrayal of the Egyptian queen.

Allegorical and Moralizing Subjects: Works like Patience, Prudentia (possibly the Nude Woman on Armor), and Death and the Sleeping Woman conveyed moral lessons or contemplated human existence, often employing complex symbolism.

Genre Scenes and Peasant Life: Like his brother Hans Sebald, Barthel occasionally depicted scenes of everyday life, including peasants, soldiers, and market scenes, sometimes with a satirical or humorous undertone.

Erotic and Nude Studies: Beham was unafraid to explore the human form, including nude figures in both classical and contemporary contexts. Some of these works, like the Battle of Eighteen Nude Men, showcase his understanding of anatomy and dynamic movement, while others had a more overtly erotic appeal, catering to a specific segment of the market.

His technical finesse in engraving was remarkable. He could achieve a wide range of tonal values and textures, creating images of great plasticity and detail despite their small size. His line work was confident and expressive, capable of conveying both delicate nuances and powerful forms.

Key Works and Their Significance

Beyond the Portrait of Chancellor Leonhard von Eck already mentioned, several other works by Barthel Beham deserve specific attention to understand the breadth and depth of his artistry.

Portrait of Ludwig X, Duke of Bavaria (c. 1530): This portrait of one of his ducal patrons showcases Beham's ability to convey authority and individual character. Ludwig X, like his brother Wilhelm IV, was a key figure in Bavarian politics and culture, and Beham’s portrayal would have served to solidify his image.

Engravings of Cleopatra (e.g., c. 1520-1525): These prints, often depicting Cleopatra in the nude with the asp, demonstrate his early engagement with classical subjects and the female form. They show the influence of Italian Renaissance models, possibly via Marcantonio Raimondi, but with a Northern sensibility in the figure type and execution.

Judith with the Head of Holofernes (engraving, c. 1525): This popular Old Testament subject, depicting the heroic Judith after she has slain the Assyrian general Holofernes, was treated by many Renaissance artists. Beham’s version, Judith Seated on the Body of Holofernes, is a powerful and compact composition, emphasizing Judith's resolve and the gruesome reality of her deed. The dynamic pose and anatomical rendering are noteworthy.

Battle of Eighteen Nude Men (engraving, c. 1528): This energetic and complex print displays Beham's skill in depicting multiple figures in dynamic action. It reflects the Renaissance interest in anatomical studies and the depiction of the human body in motion, reminiscent of works by Italian artists like Antonio Pollaiuolo.

Der Welt Lauf (The Way of the World) (engraving, c. 1525): This allegorical print is thought to reflect Beham's disillusionment following the suppression of the Peasants' War and his own experiences with authority. It depicts a chaotic scene with figures representing folly, injustice, and the overturned social order, with a sense of despair over the powerlessness of justice.

Adam and Eve (engraving, c. 1525-1530): A common theme for Northern Renaissance artists (Dürer’s 1504 engraving is iconic), Beham’s interpretations show his own approach to rendering the human form and the biblical narrative, often with a focus on the psychological moment of the Fall.

Portrait of a Man with a Parrot (c. 1529): This painting demonstrates his skill in capturing not just the likeness but also the personality of his sitters, often incorporating symbolic elements like the parrot, which could signify various attributes depending on context, such as eloquence or exoticism.

These works, whether paintings or engravings, highlight Beham's versatility, his technical mastery, and his engagement with the artistic and intellectual currents of his time. His portraits are valued for their psychological depth, while his prints are admired for their technical brilliance and thematic variety.

Collaboration and Artistic Circle

Barthel Beham did not operate in an artistic vacuum. His closest artistic connection was undoubtedly with his older brother, Hans Sebald Beham. They shared a similar artistic upbringing in Nuremberg, were both profoundly influenced by Dürer, and both became leading figures among the "Little Masters." They were also linked by the "godless painters" scandal and their subsequent expulsion from Nuremberg. While their styles are distinct, with Hans Sebald often displaying a more robust and sometimes coarser vitality, their thematic interests and technical approaches in printmaking often overlapped. There is evidence of shared motifs and a general stylistic kinship, suggesting ongoing dialogue and mutual influence, even after their paths diverged geographically.

Georg Pencz, the third member of the "godless painters" trio, was another important contemporary. Like the Beham brothers, Pencz was a skilled engraver and later a successful painter, also known for his portraits and mythological scenes. He, too, traveled to Italy and absorbed Italian Renaissance and Mannerist influences. The shared experience of the 1525 trial and exile likely forged a bond between these artists, even if their individual careers took them in different directions.

In Munich, Barthel Beham would have been aware of other artists working for the Bavarian court, such as Albrecht Altdorfer (though Altdorfer was primarily based in Regensburg, he undertook commissions for Wilhelm IV, notably The Battle of Alexander at Issus). Other painters like Ludwig Refinger and Melchior Feselen were also active in the ducal circle. While direct collaborations might not be extensively documented, the court environment would have fostered a degree of artistic exchange and competition.

The broader context of German art at this time included figures like Lucas Cranach the Elder, court painter in Saxony and a key artist of the Reformation; Hans Holbein the Younger, whose international career took him from Augsburg and Basel to the English court; and Matthias Grünewald, whose intensely expressive religious works like the Isenheim Altarpiece offered a different artistic path. While Beham's direct interaction with all these figures may have been limited, their collective work defines the rich and diverse landscape of German Renaissance art.

Artistic Style and Development

Barthel Beham's artistic style evolved significantly over his relatively short career, shaped by his training, his personal experiences, and his exposure to different artistic currents.

His early phase, centered in Nuremberg (c. 1520-1525), is heavily indebted to Albrecht Dürer. This is evident in the precise, detailed line work of his engravings, the often traditional religious and mythological subject matter, and a certain Northern European gravity in the figure types. However, even in this early period, an interest in Italian Renaissance forms, likely absorbed through prints by artists like Marcantonio Raimondi, is apparent, particularly in his treatment of the nude and classical narratives.

The expulsion from Nuremberg in 1525 and his subsequent move to Munich and service at the Bavarian court marked a new phase. While he continued to produce engravings, his focus increasingly shifted towards portraiture. His painted portraits from this period (late 1520s - 1530s) are characterized by their sharp observation, psychological insight, and meticulous execution. They possess a clarity and realism that places him among the foremost German portraitists of his generation. The smooth, almost enameled finish and the careful rendering of textures are hallmarks of his painterly style.

The presumed journey(s) to Italy in the 1530s introduced a Mannerist influence, particularly visible in his later prints. Figures may appear more elongated, their poses more artificial and dynamic (figura serpentinata), and compositions more complex and spatially ambiguous. This reflects an engagement with the cutting-edge artistic developments in Italy, demonstrating his adaptability and desire to incorporate new stylistic vocabularies. Had he lived longer, it is likely this Mannerist tendency would have become even more pronounced in his work.

Throughout his career, a key characteristic of Beham's art, especially his prints, was his technical virtuosity. As a "Little Master," he demonstrated an extraordinary ability to create intricate and expressive images on a small scale, a testament to his skill with the burin and his understanding of the engraving medium.

Symbolism and Iconography in Beham's Art

Like many Renaissance artists, Barthel Beham employed a rich vocabulary of symbols and iconographic conventions in his work, particularly in his engravings. These visual codes would have been readily understood by his educated contemporaries, adding layers of meaning to his images.

In his religious prints, traditional Christian iconography abounded, but sometimes with a twist that reflected the era's theological debates. For instance, the way Christ or saints were depicted could subtly align with or critique specific doctrinal points. His allegorical prints, such as Der Welt Lauf, used personifications and symbolic objects to comment on social and moral issues, reflecting a humanist concern with virtue, vice, and the human condition.

Classical mythology provided another rich source of symbolism. Figures like Venus, Hercules, or Cleopatra carried established connotations related to love, strength, or tragic fate. Beham’s reinterpretation of these myths often focused on their dramatic or human aspects. The depiction of the nude, central to many of these classical and allegorical scenes, was itself symbolic of the Renaissance rediscovery of classical ideals of beauty and the humanist focus on the human form.

Even in his portraits, seemingly straightforward depictions could contain symbolic elements. The objects held by a sitter, their attire, or the inclusion of animals (like the parrot in Portrait of a Man with a Parrot) could allude to the sitter's status, profession, character traits, or intellectual interests. For example, a skull might symbolize mortality (a memento mori), while a book could indicate learning.

The context of the Reformation also imbued certain images with new or heightened symbolic weight. Themes of judgment, salvation, and the critique of worldly or ecclesiastical power resonated strongly in this period of profound religious upheaval. Beham's own experiences, including his brush with charges of heresy, likely sensitized him to the power of images to convey complex and sometimes subversive ideas.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Barthel Beham died prematurely in 1540 while in Italy, at the age of only 38. Despite his short life, he left behind a significant body of work that secures his place in the history of German Renaissance art. His primary legacy rests on two pillars: his contributions as a "Little Master" engraver and his achievements as a portrait painter.

As an engraver, Beham was among the most technically gifted of his generation. His small, intricate prints were widely disseminated and collected, contributing to the visual culture of the time and influencing other printmakers. The "Little Masters" collectively played a crucial role in popularizing various themes – classical, religious, genre – and in making art accessible to a broader audience beyond elite patrons. Beham's skill in rendering detail, texture, and human emotion in the demanding medium of engraving remains admired.

As a portrait painter at the Bavarian court, Beham produced images of remarkable psychological depth and technical refinement. His portraits of Chancellor von Eck and members of the ducal family are important documents of the personalities and power structures of their time, and they stand as high points of German Renaissance portraiture. He demonstrated an ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the inner character of his sitters, a quality that aligns him with the greatest portraitists of the era, such as Hans Holbein the Younger or Titian in Italy.

While perhaps not as universally recognized as Albrecht Dürer or Holbein, Barthel Beham's work is held in high esteem by art historians and connoisseurs. His prints are found in major museum collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum in London, and the Albertina in Vienna. His paintings, though fewer in number, are also prized possessions of leading galleries.

His career also serves as a compelling case study of an artist navigating the turbulent waters of the Reformation. His early radicalism, expulsion from Nuremberg, and subsequent success in a Catholic court illustrate the complex choices and adaptations artists had to make in a rapidly changing world.

Conclusion

Barthel Beham was an artist of exceptional talent whose career, though brief, spanned a pivotal period in German art history. From his early Dürer-influenced engravings in Nuremberg to his sophisticated court portraits in Munich and his later engagement with Italian Mannerism, Beham demonstrated a remarkable versatility and technical mastery. As one of the "Little Masters," he contributed significantly to the flourishing of German printmaking, creating works of intricate beauty and diverse subject matter. His portraits reveal a keen psychological insight and a refined painterly technique, capturing the likenesses of some of the key figures of his time. Overshadowed at times by more famous contemporaries, Barthel Beham nevertheless remains a vital and fascinating figure, whose art provides a rich window into the artistic, intellectual, and religious currents of the Northern Renaissance. His legacy endures in the exquisite quality of his surviving works, which continue to engage and impress viewers centuries later.