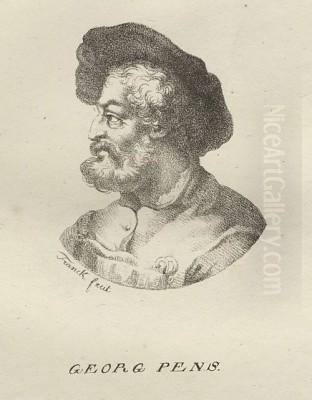

Georg Pencz stands as a significant figure in the German Renaissance, an artist whose career bridged the towering legacy of Albrecht Dürer and the potent influence of Italian art. Active primarily in Nuremberg, Pencz excelled as both a painter and an engraver, earning a place among the celebrated "Little Masters" for his intricate printmaking. His life, marked by artistic innovation, religious controversy, and engagement with the leading cultural currents of his time, offers a fascinating window into the complexities of 16th-century Northern European art. Born around 1500 and passing away in 1550, Pencz navigated a period of profound change, leaving behind a body of work admired for its technical skill and stylistic synthesis.

Early Life and Formation in Dürer's Orbit

The precise origins of Georg Pencz remain somewhat uncertain, with scholarly consensus pointing to a birth around the year 1500. While Nuremberg is often cited, the area near Westheim in Franconia has also been proposed as his possible birthplace. What is clearer is his early connection to Nuremberg, the vibrant artistic and commercial heart of Franconia and a major center of the German Renaissance. By the early 1520s, Pencz was active in the city, and evidence strongly suggests he spent time in the workshop of the preeminent German artist of the era, Albrecht Dürer.

Joining Dürer's workshop before 1523 placed Pencz at the epicenter of artistic innovation in Northern Europe. Dürer was not only a master painter and printmaker but also a theorist and intellectual deeply engaged with Italian Renaissance ideas. Working under Dürer, even if briefly, would have exposed Pencz to the highest standards of craftsmanship, a rigorous approach to drawing and composition, and an awareness of the artistic developments south of the Alps. Dürer's influence is palpable in Pencz's early work, particularly in the precision and detail characteristic of his engravings.

The "Godless Painters" Incident

Pencz's early career in Nuremberg was dramatically interrupted in 1525. This was a time of intense religious ferment following Martin Luther's initiation of the Protestant Reformation. Radical interpretations of religious doctrine flourished, challenging established church authority and sometimes civic order. Pencz, along with fellow artists Barthel Beham and Sebald Beham – brothers who had also likely spent time in Dürer's circle – found themselves accused of holding radical religious views.

The specific charges included expressing skepticism about key Christian tenets like the divinity of Christ, the value of baptism, and the authority of scripture. Some accounts even label them "godless painters." These views aligned them with more radical reformers and potentially Anabaptist or spiritualist movements, which were viewed with suspicion by Nuremberg's Lutheran-leaning city council. Consequently, Pencz and the Beham brothers were expelled from the city in January 1525. This incident highlights the volatile intersection of art, religion, and politics during the Reformation era.

Though the expulsion was a significant setback, it was relatively short-lived for Pencz. He was permitted to return to Nuremberg later the same year, although the Beham brothers faced a longer exile. This episode, however, underscores a tension present throughout Pencz's career: despite his alleged skepticism, traditional religious subjects would remain a significant part of his artistic output, perhaps reflecting market demands or a more complex personal relationship with faith than the 1525 trial suggests.

Italian Journeys and Artistic Transformation

A pivotal element in Georg Pencz's artistic development was his engagement with Italian art. Evidence points to at least one, and possibly two, significant journeys south of the Alps. The most documented trip likely occurred between 1526 and 1528, following his initial troubles in Nuremberg. During this period, he is believed to have spent time in Northern Italy, possibly Venice, and perhaps traveled as far as Rome. A later trip, possibly around 1539-1540, is also suggested by stylistic developments in his work.

Crucially, during his time in Italy, Pencz is thought to have encountered the work, and possibly the workshop, of Marcantonio Raimondi. Raimondi was a highly influential engraver, renowned for his technical mastery and, most importantly, for his reproductive prints after the designs of High Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael. Studying Raimondi's techniques would have profoundly shaped Pencz's own approach to engraving, refining his line work and modeling of form.

Beyond printmaking, the broader exposure to Italian art left an indelible mark on Pencz's style. He absorbed the lessons of the High Renaissance, evident in the clarity of his compositions and the idealized, often classical, treatment of figures. The influence of Raphael, whose work Pencz likely knew both directly and through Raimondi's prints, can be seen in the grace and harmony of some compositions. Furthermore, elements associated with Mannerism, the sophisticated and sometimes artificial style emerging in Italy, are apparent, particularly in the elongated proportions and elegant poses found in some of his figures, drawing comparisons to artists like Bronzino. The rich colors and textures associated with the Venetian school, perhaps encountered through artists like Titian, may also have informed his painterly technique.

Mature Career in Nuremberg: City Painter and Portraitist

Upon his return from Italy, Pencz re-established himself in Nuremberg. His talent was recognized by the city authorities, overcoming any lingering stigma from the 1525 incident. By 1529, he was firmly settled back in the city, and in 1532, he received a significant mark of official favor when he was appointed one of Nuremberg's official city painters. This position likely involved various commissions from the city council, potentially including civic portraits and decorative projects.

Indeed, Pencz played a role in the decoration of the Nuremberg Town Hall (Rathaus), a prestigious project that showcased the city's wealth and status. While the exact nature and extent of his contribution are debated, his involvement signifies his standing within the Nuremberg artistic community. Following Dürer's death in 1528, a void existed at the top of the city's artistic hierarchy, and Pencz emerged as one of the leading figures capable of filling it, alongside contemporaries like the Beham brothers (once they returned) and other Nuremberg artists.

During this mature phase, Pencz developed a strong reputation as a portrait painter. His portraits are characterized by a sharp, linear precision likely honed through his engraving work, combined with a smooth, enamel-like finish that recalls Italian influences, particularly the courtly style of Mannerist portraitists like Bronzino. He rendered his sitters with psychological acuity, capturing individual likeness while often imbuing them with a sense of dignity and reserve. Notable examples include the sensitive Portrait of a Youth and the striking Portrait of Field Marshal Sebald Schirmer (sometimes mistakenly identified from source misinterpretations). These works rival the best Northern European portraiture of the time, demonstrating a distinct style compared to the slightly earlier, more robust realism of Dürer or the courtly elegance of Lucas Cranach the Elder, or the penetrating likenesses of Hans Holbein the Younger.

Pencz the Painter: Synthesis of North and South

Georg Pencz's paintings exemplify the fruitful synthesis of Northern European traditions and Italian Renaissance ideals that characterized much of German art in the generation after Dürer. His technical approach often retained a Northern emphasis on meticulous detail and linear clarity, yet his compositions, figure types, and handling of light and color reveal a deep engagement with Italian models.

His subject matter in painting spanned the typical Renaissance genres. Religious narratives remained important, with works like The Story of Joseph (c. 1544) and The Judgement of Solomon (c. 1547) showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with narrative clarity. These works often display the balanced arrangements and idealized figures associated with the High Renaissance, particularly Raphael, whose influence permeated European art.

Mythological and allegorical themes also feature prominently, reflecting the Renaissance fascination with classical antiquity and humanist thought. Paintings such as Venus and Amor or the Allegory of Justice allowed Pencz to explore the nude figure, drawing on Italian precedents for anatomical understanding and graceful posing. His treatment often combines classical ideals with a certain Northern coolness or restraint. The sharp outlines and smooth, polished surfaces seen in works like these led to comparisons with Florentine Mannerists such as Bronzino, suggesting Pencz was attuned to the latest stylistic developments in Italy.

His portraiture, as mentioned, was a significant part of his painted oeuvre. He captured the rising merchant class and civic leaders of Nuremberg, providing valuable records of the society in which he lived. The Portrait of Sigismund Baldinger (likely the sitter sometimes referred to as 'Schirmer' or 'Schmierz' due to transcription issues) is a prime example of his ability to convey status and personality through careful observation and refined technique. His paintings, while perhaps less numerous than his prints, demonstrate his versatility and his mastery of contemporary European styles.

Pencz the Engraver: A Leading "Little Master"

While a respected painter, Georg Pencz achieved perhaps his widest and most lasting renown as an engraver. He belongs to a group of German printmakers active in the generation after Dürer known as the "Little Masters" (Kleinmeister). This term refers not to a lack of skill, but to the typically small scale of their engravings, which were often produced for the burgeoning collectors' market rather than for large-scale devotional use. Other key figures in this group include the Beham brothers (Barthel and Sebald) and Heinrich Aldegrever.

Pencz was among the most technically gifted and prolific of the Little Masters. His training in Dürer's workshop provided a foundation in the precise art of burin engraving, a technique Dürer himself had elevated to unprecedented levels of sophistication. Pencz built upon this Northern tradition, likely refining his technique further through exposure to the work of earlier masters like Martin Schongauer and, crucially, through his engagement with the engravings of Marcantonio Raimondi in Italy. Raimondi's systematic approach to modeling form with parallel and cross-hatched lines, often used to translate the tonal values of paintings into print, clearly influenced Pencz's mature engraving style.

His engraved output was diverse. He produced numerous series on biblical themes, such as the Story of Joseph and scenes from the life of Christ, demonstrating narrative skill within the confines of small plates. Mythological subjects were also frequent, including series depicting classical gods, goddesses, and heroes, reflecting the humanist interests of his patrons. His series illustrating Petrarch's Triumphs, such as The Triumph of Chastity over Love, translated literary themes into visual form.

One particularly interesting series is the Children of the Planets, which depicts activities associated with the astrological influence of each planet (e.g., warfare for Mars, agriculture for Saturn). These prints offer fascinating glimpses into contemporary life and beliefs, blending genre scenes with astrological concepts. Pencz's engravings are characterized by their fine detail, elegant figure drawing, clear compositions, and masterful control of the burin, achieving subtle tonal gradations and textural effects.

The Master I.B. Question

A persistent question in the scholarship surrounding Georg Pencz concerns his relationship to the anonymous printmaker known as the "Master I.B." This monogrammist, active around the same time, produced engravings similar in style and subject matter to Pencz's work. For many years, it was widely assumed that Pencz and the Master I.B. were one and the same, with the monogram representing an early phase or perhaps an alternative signature.

The stylistic similarities are indeed striking, particularly in the handling of figures, the compositional structures, and the technical approach to engraving. Both Pencz and Master I.B. show a strong affinity for Italian Renaissance models, particularly the circle of Raphael as transmitted through Raimondi. Subjects favored by both include mythology, allegory, and genre scenes, often rendered with a similar blend of Northern precision and Italianate grace.

However, more recent scholarship has tended to separate the two identities. Subtle differences in technique, figure types, and artistic sensibility have led many experts to conclude that Master I.B. was likely a distinct artist, albeit one working in close proximity to Pencz, possibly also in Nuremberg, and certainly sharing similar influences. While the debate may not be definitively closed, the current consensus leans against identifying Pencz with Master I.B., suggesting instead a complex milieu of highly skilled engravers working in Southern Germany during this period, all responding to the dual legacies of Dürer and the Italian Renaissance.

Themes and Iconography

The range of themes tackled by Georg Pencz reflects the broad interests of the Renaissance era. His religious works covered both Old and New Testament subjects, often presented as clear narratives suitable for didactic purposes or private devotion. Even after the "godless painters" incident, biblical stories remained a staple of his output, suggesting either a reconciliation with acceptable forms of piety or a pragmatic response to market demand. Works like The Good Samaritan and The Conversion of St. Paul fit comfortably within traditional Christian iconography.

Mythology and classical allegory provided Pencz with opportunities to explore humanist themes and depict the idealized human form, particularly the nude. Subjects drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses or other classical sources were popular throughout Renaissance Europe, and Pencz's interpretations often emphasize elegance and narrative clarity. These works catered to a sophisticated audience familiar with classical literature and appreciative of Italianate style.

His portraiture, both painted and occasionally engraved, served the practical function of recording likenesses but also participated in the Renaissance emphasis on individual identity and status. His sitters, often members of Nuremberg's prosperous patrician and merchant classes, are presented with a combination of realism and dignified composure.

Furthermore, prints like the Children of the Planets series touch upon genre themes and contemporary life, albeit filtered through an astrological framework. This diversity of subject matter – spanning the sacred, the classical, the contemporary, and the personal – marks Pencz as a versatile artist fully engaged with the intellectual and cultural currents of his time. He navigated the demands of patrons, the influence of artistic trends from both North and South, and the turbulent religious climate of the Reformation.

Later Life, Final Appointment, and Legacy

Georg Pencz remained a leading artistic figure in Nuremberg throughout the 1530s and 1540s. His reputation extended beyond the city, attracting attention from prominent patrons. In 1550, this recognition culminated in a prestigious appointment: he was called to serve as court painter to Duke Albrecht of Prussia in Königsberg (modern-day Kaliningrad). This position represented a significant honor and potentially greater financial security.

Tragically, Pencz was unable to enjoy this new role for long. He died in the autumn of 1550, possibly while en route to Königsberg, perhaps in Leipzig, or shortly after arriving. He was only around 50 years old. Some accounts suggest that despite his success and official appointments, he may have faced financial difficulties towards the end of his life, a situation not uncommon even for respected artists of the period.

Georg Pencz's legacy lies in his successful fusion of German artistic traditions with Italian Renaissance innovations. As a painter, he brought a sophisticated, internationally informed style to Nuremberg, particularly evident in his polished portraits and mythological scenes. As an engraver, he was a key figure among the Little Masters, producing works of exceptional technical refinement and disseminating Renaissance forms and themes through the widely circulated medium of print.

His engravings, in particular, were influential, collected across Europe and serving as models for other artists and craftsmen. He stands alongside Albrecht Dürer, the Beham brothers, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Hans Holbein the Younger, and Albrecht Altdorfer as one of the major figures of the German Renaissance. His ability to absorb and adapt diverse influences – from the meticulousness of the Northern tradition learned under Dürer to the grace and grandeur of Raphael and the elegance of Mannerists like Bronzino, all filtered through the printmaking innovations of Raimondi – resulted in a unique and accomplished artistic voice.

Conclusion: A Master of Synthesis

Georg Pencz occupies a crucial position in the narrative of 16th-century German art. Emerging from the shadow of the great Albrecht Dürer, he navigated the complex artistic landscape shaped by the Reformation and the pervasive influence of the Italian Renaissance. His career, though marked by early controversy and cut short prematurely, demonstrates a remarkable capacity for stylistic synthesis and technical mastery across both painting and engraving.

His paintings, particularly his insightful portraits and elegant mythological scenes, showcase his absorption of Italian ideals of form and composition, blended with a Northern precision. His engravings solidified his reputation as one of the foremost "Little Masters," whose small-scale, intricate works were admired for their technical brilliance and diverse subject matter. Through his art, Pencz helped to shape the character of the German Renaissance after Dürer, creating a body of work that remains compelling for its skill, sophistication, and reflection of a pivotal era in European cultural history.