Introduction: Anthonie de Lorme in the Pantheon of Dutch Masters

Anthonie de Lorme (also spelled Delorme) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure among the constellation of artists who illuminated the Dutch Golden Age. Active primarily in Rotterdam, he carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of church interiors, a genre that flourished in the newly independent and prosperous Dutch Republic. While names like Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, and Frans Hals often dominate discussions of this era, specialists like De Lorme contributed immensely to the rich tapestry of Dutch art, offering unique perspectives on the spiritual and communal spaces of their time. His work is characterized by a profound understanding of perspective, a masterful handling of light and shadow, and an evolving approach that moved from imaginative, somewhat fantastical architectural compositions to more realistic depictions of existing ecclesiastical structures. This exploration will delve into his life, the artistic milieu in which he operated, his stylistic development, key works, influences, and his enduring, albeit quiet, legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Anthonie de Lorme's origins are traced to Tournai, in present-day Belgium, where he is believed to have been born sometime between 1600 and 1610. The exact date remains elusive, a common challenge when researching artists from this period. His parents are recorded as having married in Antwerp, a major artistic and commercial hub, before relocating to the northern Netherlands around 1612. This migration pattern was not uncommon, as many sought refuge or opportunity in the burgeoning Dutch Republic, which had formally broken away from Spanish Hapsburg rule.

The young De Lorme is first documented in Rotterdam in 1627. This city, a rapidly growing port, would become his lifelong home and the primary setting for his artistic endeavors. It was here that his formal artistic training likely commenced or solidified. Art historical records suggest that he was a pupil of two notable artists: Jan van Vucht and Bartolomeus van Bassen. Jan van Vucht (c. 1603–1637) was himself a painter of architectural scenes, particularly church interiors, often with a fantastical element. The age proximity between De Lorme and Van Vucht has led some scholars to question the traditional master-apprentice dynamic, suggesting they might have been closer to contemporaries or collaborators, though De Lorme did act as a witness for Van Vucht in a legal matter in 1627, which could imply a closer professional tie.

Bartolomeus van Bassen (c. 1590–1652) was another significant figure in the development of architectural painting. Active in Delft and The Hague, Van Bassen was not only a painter but also an architect, which lent a particular structural integrity and understanding to his painted interiors of palaces and churches, both real and imagined. His influence on De Lorme can be seen in the latter's meticulous attention to architectural detail and the construction of believable, if sometimes idealized, spaces. The tutelage or influence of these artists provided De Lorme with a solid foundation in the specialized techniques required for architectural painting, particularly the complex rules of linear perspective.

The Dutch Golden Age: A Fertile Ground for Artistic Innovation

To fully appreciate Anthonie de Lorme's contribution, it is essential to understand the unique cultural and religious climate of the 17th-century Dutch Republic. The Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) culminated in Dutch independence and ushered in an era of unprecedented economic prosperity, maritime dominance, and cultural flourishing known as the Dutch Golden Age. This period saw a seismic shift in art patronage and subject matter.

The Reformation had taken firm root in the Netherlands, with Calvinism becoming the dominant faith. Unlike the Catholic Church, which was a major patron of religious art in Southern Europe, Calvinist churches were typically austere, eschewing elaborate decorations and iconic imagery. This led to a decline in demand for traditional large-scale religious altarpieces. However, it paradoxically opened up new avenues for artists. A burgeoning, affluent middle class – merchants, guild members, civic leaders – emerged as the new patrons. They desired art that reflected their lives, values, and environment.

This shift fueled the popularity of genres such as portraiture (Frans Hals, Rembrandt), landscapes (Jacob van Ruisdael, Meindert Hobbema), seascapes (Willem van de Velde the Younger), still lifes (Willem Kalf, Pieter Claesz), and genre scenes depicting everyday life (Jan Steen, Adriaen van Ostade, Pieter de Hooch). Architectural painting, particularly of church interiors, also found a receptive audience. These paintings were not necessarily devotional in the traditional sense but often celebrated civic pride, the beauty of these communal structures, or served as reminders of order, piety, and the transience of life (vanitas). The clean, light-filled spaces of Protestant churches, or the grander, sometimes imagined, Gothic structures, offered artists like De Lorme ample opportunity to explore perspective, light, and atmosphere.

The artistic centers of Haarlem, Amsterdam, Delft, and Rotterdam each developed their own nuances, but there was a shared emphasis on realism, meticulous detail, and technical skill. Artists often specialized, becoming masters of a particular genre. De Lorme's specialization in church interiors placed him within a distinguished group of painters who focused on capturing the essence of these significant public and spiritual buildings.

De Lorme's Artistic Style: Perspective, Light, and Atmosphere

Anthonie de Lorme's artistic style is primarily defined by his sophisticated use of linear perspective and his nuanced handling of light and shadow, often creating a serene yet sometimes dramatically lit atmosphere within his depicted church interiors. His early works often feature "imaginary" or "fantastical" church interiors. These were not necessarily direct transcriptions of existing buildings but rather idealized or composite constructions, allowing the artist greater freedom in arranging architectural elements to achieve a desired aesthetic or dramatic effect. This approach was common among early architectural painters like Hendrick van Steenwijck the Elder and his son, Hendrick van Steenwijck the Younger, who often populated their scenes with biblical narratives.

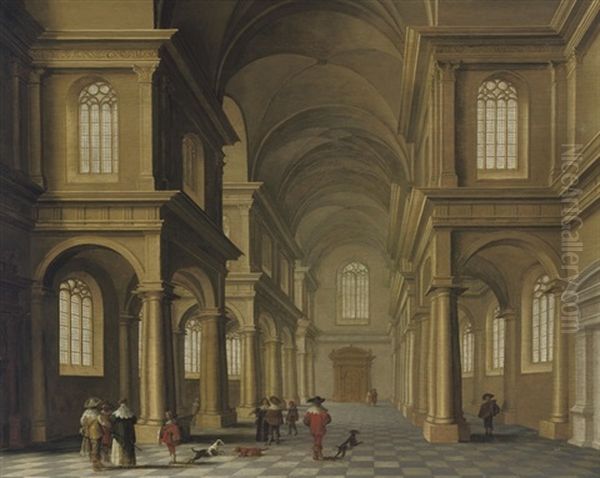

A hallmark of De Lorme's compositions is the strong emphasis on single-point perspective, where parallel lines converge towards a distant vanishing point, creating a powerful illusion of depth and recession. This technique draws the viewer's eye deep into the pictorial space, often down a long nave towards an altar or a brightly lit choir. The architectural elements – columns, arches, vaults, and windows – are rendered with precision, showcasing his understanding of structural forms.

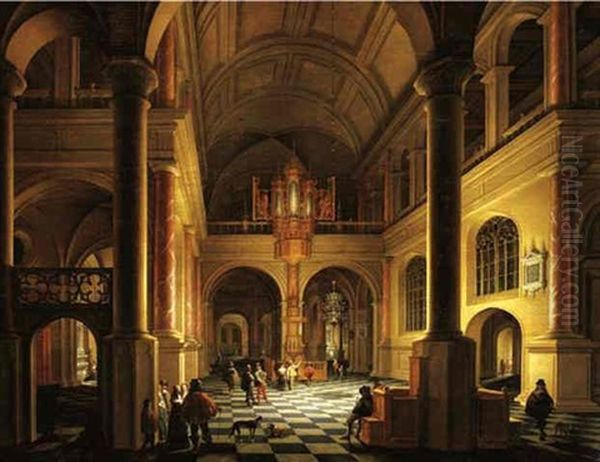

Light plays a crucial role in De Lorme's paintings. He was adept at capturing the subtle gradations of daylight filtering through stained glass or clear windows, illuminating specific areas while leaving others in soft shadow. In some works, particularly those depicting evening services or nocturnal views, candlelight becomes the primary source of illumination, casting long shadows and creating a more intimate, sometimes mysterious, ambiance. This interplay of light and dark (chiaroscuro) not only enhances the three-dimensionality of the architecture but also contributes significantly to the mood of the painting. While not as dramatic as Caravaggio or Rembrandt in their use of chiaroscuro for narrative emphasis, De Lorme employed it effectively to define space and evoke a sense of tranquility or solemnity.

Later in his career, particularly from the 1650s onwards, De Lorme increasingly turned his attention to depicting actual, identifiable churches, most notably the Sint-Laurenskerk (St. Lawrence Church) in his home city of Rotterdam. This shift may reflect a growing market preference for recognizable local landmarks or a personal artistic evolution towards greater realism. Even in these more "realistic" depictions, however, he often took artistic liberties, perhaps altering proportions or lighting for compositional or atmospheric effect.

The figures that populate his church interiors are typically small in scale, serving to emphasize the grandeur of the architecture and to provide a sense of human presence and activity – worshippers, onlookers, or even dogs. These figures were often painted by other artists, a common collaborative practice in the Dutch Golden Age. Anthonie Palamedesz. and Ludolf de Jongh are among those known to have provided staffage for De Lorme's architectural settings.

Masterpieces and Notable Works

Several key works exemplify Anthonie de Lorme's skill and artistic concerns. Among his most celebrated are his various depictions of the Sint-Laurenskerk in Rotterdam.

One such example, often titled Interior of the St. Laurens Church, Rotterdam, which can be dated to various points in his mature period (e.g., a version around 1640-1645, another noted as 1656, and a Laureskerk interior from 1662), showcases his mastery. These paintings typically present a view down the nave, with rows of columns leading the eye towards the brightly lit choir. The intricate details of the Gothic architecture, such as the ribbed vaults, tracery of the windows, and funerary monuments, are rendered with care. The play of light, often streaming in from high windows, illuminates the stone surfaces and creates a sense of airy spaciousness. The small figures scattered throughout the scene – perhaps a minister preaching, groups of burghers conversing, or children playing – add life and context, reminding the viewer that these were active communal spaces.

Another significant work is Protestant Church Interior (c. 1640-1645). While perhaps more generalized or imaginative than his later Laurenskerk views, it embodies his characteristic style. The strong perspectival lines, the careful delineation of architectural forms, and the subtle handling of light create a convincing and immersive interior space. The atmosphere is one of quiet contemplation, typical of the Calvinist ethos.

His Interior of the Great Church, Rotterdam (1656) is another testament to his skill. The "Great Church" usually refers to the Sint-Laurenskerk, the principal church of Rotterdam. In these works, De Lorme often focused on the interplay between the massive stone structure and the ephemeral effects of light. The inclusion of details like elaborate organ cases, pulpits, and memorial plaques adds to the realism and historical interest of these paintings.

It's important to note that De Lorme often painted multiple versions or variations of similar views, sometimes with different lighting conditions (day vs. night) or with figures by different collaborators. This practice was not unusual, as successful compositions were often in demand. His dedication to the theme of church interiors, particularly those of Rotterdam, makes his oeuvre a valuable visual record of these significant civic and religious structures.

Collaborations and Professional Life

The practice of collaboration was widespread in the Dutch Golden Age, particularly between artists specializing in different areas. Architectural painters like De Lorme often focused on the complex setting, leaving the addition of figures (staffage) to artists who specialized in genre scenes or portraiture. This division of labor allowed for greater efficiency and often resulted in a higher quality finished product, combining the strengths of multiple talents.

Anthonie de Lorme is known to have collaborated with several artists. Anthonie Palamedesz. (1601–1673), a contemporary active in Delft, was known for his genre scenes, particularly "merry companies" and guardroom scenes, as well as portraits. Palamedesz. occasionally provided the figures for De Lorme's church interiors, adding a lively human element to the otherwise static architectural spaces.

Ludolf de Jongh (1616–1679), another Rotterdam-based artist, also collaborated with De Lorme, notably on some of his depictions of the Sint-Laurenskerk. De Jongh was a versatile painter, producing portraits, genre scenes, and hunting scenes. His figures, often elegantly dressed burghers or simple worshippers, integrate seamlessly into De Lorme's meticulously rendered interiors.

There is also mention of a collaboration with Jan Tengenaeus on a work dated 1662, though Tengenaeus is a less widely known figure. These collaborations highlight the interconnectedness of the artistic community and the pragmatic approaches artists took to production and meeting market demands.

Beyond his painting activities, there is some evidence to suggest that Anthonie de Lorme may have run a shop selling paintings and art supplies. This would not have been unusual for an artist of the period, providing an additional source of income and a hub for artistic materials and commerce. He married Maertjie Floris in Rotterdam in 1647, further rooting him in the city's social and professional fabric. He remained active in Rotterdam until his death in 1673.

Influences and Contemporaries in Architectural Painting

Anthonie de Lorme's work did not develop in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant tradition of architectural painting that had roots in earlier Flemish art (e.g., Hans Vredeman de Vries, who published influential treatises on perspective) and evolved significantly in the Dutch Republic.

His teachers, Jan van Vucht and Bartolomeus van Bassen, were crucial early influences, instilling in him the fundamentals of perspective and the conventions of depicting architectural spaces. Van Bassen, in particular, with his dual role as architect and painter, likely emphasized structural accuracy.

Another artist whose work may have influenced De Lorme, or at least represents a parallel development, is Hougaard Gerckens (likely a misspelling of Gerard Houckgeest). Gerard Houckgeest (c. 1600–1661), along with Emanuel de Witte and Hendrick van Vliet, was a leading figure of the Delft school of architectural painting. Houckgeest was innovative in his choice of viewpoints, often opting for oblique angles and complex spatial arrangements rather than the more traditional frontal views down the nave. He was particularly known for his depictions of the Nieuwe Kerk and Oude Kerk in Delft, often with a focus on tomb monuments, like that of William the Silent. While De Lorme generally favored more central perspectives, the broader trend towards greater naturalism and sophisticated light effects seen in the Delft school would have been part of the artistic discourse of the time.

Pieter Saenredam (1597–1665) stands as a towering figure in Dutch architectural painting. Active primarily in Haarlem and Utrecht, Saenredam was renowned for his highly accurate, almost portrait-like depictions of specific church interiors. He would make meticulous preparatory drawings on site, complete with measurements, which he then translated into serene, light-filled paintings characterized by their pale tonalities and sense of calm order. Saenredam's commitment to topographical accuracy set a new standard for the genre, moving away from the more fantastical compositions of earlier architectural painters. De Lorme's later shift towards depicting real churches like the Sint-Laurenskerk can be seen as part of this broader trend towards realism, though his style retained a slightly warmer, more atmospheric quality compared to Saenredam's cool precision.

Emanuel de Witte (c. 1617–1692), active in Delft and later Amsterdam, was another master of the church interior. De Witte's paintings are often characterized by more dynamic compositions, a richer play of light and shadow, and a greater emphasis on the human element, with figures actively engaged in various activities within the church space. He often depicted bustling scenes, sermons in progress, or groups of people admiring the architecture, creating a more lively and atmospheric feel than the often more static and contemplative scenes of Saenredam or De Lorme.

Other notable architectural painters of the era include Dirck van Delen (1604/05–1671), who often painted elaborate imaginary palace and church interiors with a strong sense of Baroque grandeur, and Daniel de Blieck (c. 1610–1673), who also painted church interiors in Middelburg. The collective work of these artists demonstrates the popularity and diversity of architectural painting in the Dutch Golden Age, with each artist bringing their unique vision and technical approach to the genre.

Later Career, Legacy, and Historical Significance

Anthonie de Lorme continued to paint throughout the mid-17th century, solidifying his reputation as a specialist in church interiors, particularly those of Rotterdam. His transition from predominantly imaginary architectural scenes to more faithful representations of existing structures, like the Sint-Laurenskerk, marks an important development in his career. These later works serve not only as artistic achievements but also as valuable historical documents.

Indeed, one of the remarkable aspects of De Lorme's legacy is the role his paintings played in the 20th century. The Sint-Laurenskerk, the main subject of many of his mature works, was severely damaged during the German bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940 during World War II. After the war, when the decision was made to restore the historic church rather than demolish it, De Lorme's detailed and accurate depictions provided invaluable visual information for the architects and craftsmen involved in the painstaking reconstruction. His canvases, created three centuries earlier, thus contributed directly to the resurrection of a beloved city landmark, a testament to the enduring power and utility of art beyond its aesthetic function.

While Anthonie de Lorme may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his Dutch contemporaries like Rembrandt or Vermeer, his contribution to the specific genre of architectural painting is undeniable. He was a skilled practitioner who masterfully conveyed the scale, light, and atmosphere of sacred spaces. His works reflect the civic pride and religious sensibilities of his time, offering a window into the world of 17th-century Rotterdam.

His paintings are held in numerous public and private collections worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and various municipal museums in the Netherlands. They continue to be appreciated for their technical proficiency, their serene beauty, and their historical insights. For art historians, De Lorme's oeuvre provides important comparative material for understanding the development of architectural painting and the regional variations within Dutch art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Sacred Space

Anthonie de Lorme was a dedicated and talented artist who excelled in the specialized field of architectural painting. Working within the vibrant artistic environment of the Dutch Golden Age, he developed a distinctive style characterized by meticulous perspective, a sensitive handling of light, and a profound appreciation for the grandeur and serenity of church interiors. From his early imaginative compositions to his later, more realistic depictions of Rotterdam's Sint-Laurenskerk, his work consistently demonstrates a high level of technical skill and artistic integrity.

His collaborations with figure painters like Anthonie Palamedesz. and Ludolf de Jongh reflect the common workshop practices of the era, while his position within a lineage of architectural specialists, including his teachers Jan van Vucht and Bartolomeus van Bassen, and contemporaries like Pieter Saenredam and Emanuel de Witte, situates him firmly within a key development in Dutch art.

Perhaps his most tangible legacy, beyond the intrinsic beauty of his paintings, is the unexpected role his art played in the post-war reconstruction of Rotterdam. Anthonie de Lorme's canvases, created out of artistic passion and for contemporary patrons, transcended their original purpose to become vital historical records. He remains a noteworthy figure, a master whose careful eye and steady hand captured the enduring spirit of the sacred spaces that defined the heart of Dutch communities. His work invites us to step into the light-filled naves and shadowy aisles of a bygone era, to appreciate the quiet majesty he so skillfully portrayed.