Antoine Berjon stands as a pivotal figure in the history of French art, particularly renowned for his exquisite flower paintings and still lifes. Born in Lyon on May 17, 1754, and passing away in the same city on October 24, 1843, Berjon's life and career bridged the tumultuous late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was not only a master painter but also an influential designer and a dedicated professor, leaving an indelible mark on the Lyon School of painting and the city's famed silk industry. His journey from a craftsman in the textile trade to a celebrated artist and educator is a testament to his talent, dedication, and the unique artistic environment of Lyon.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Lyon

Lyon, Berjon's birthplace, was a thriving center for silk production, an industry that demanded high levels of artistic skill in design. This environment undoubtedly shaped Berjon's early sensibilities. His initial artistic training was under the guidance of the sculptor Antoine-Michel Perrache (1726–1779), a notable figure in Lyon. This foundational education in three-dimensional form likely contributed to the tangible, sculptural quality often observed in Berjon's later painted subjects.

Berjon's professional life began not with a paintbrush in a studio, but as a draughtsman and designer for Lyon's prestigious silk manufacturers. This role required a profound understanding of botanical forms, an eye for intricate detail, and the ability to translate natural beauty into patterns suitable for weaving. The meticulous observation of flowers and plants, essential for creating appealing textile designs, provided him with an intimate knowledge of their structure, color, and texture. This practical experience in the decorative arts would prove invaluable when he later transitioned to fine art painting, particularly in the genre of flower painting where botanical accuracy was highly prized.

The late 18th century in France was a period of artistic transition. While the Rococo style, with its lightness and frivolity, was waning, Neoclassicism, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), was gaining prominence, emphasizing order, clarity, and moral seriousness. Still life and flower painting, though sometimes considered lesser genres compared to historical or mythological subjects, had a long and respected tradition, particularly influenced by Dutch Golden Age masters.

The Parisian Sojourn: Development and Recognition

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Berjon moved to Paris around 1790 or 1791. The French capital was the undisputed center of the European art world, offering opportunities for exhibition, patronage, and interaction with leading artists. It was in Paris that Berjon truly began to establish himself as a painter. He made his debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1791, exhibiting a flower piece that garnered positive attention. The Salon was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and success there was crucial for an artist's reputation and career.

During his seventeen-year stay in Paris, Berjon continued to exhibit regularly at the Salon, presenting still lifes of flowers and fruit, as well as occasional portraits. His works were noted for their refined technique, vibrant colors, and the lifelike depiction of his subjects. In Paris, he formed friendships with other artists, including the miniaturist Jean-Baptiste Jacques Augustin (1759–1832) and the painter Claude-Jean-Baptiste Hoin (1750–1817). The influence of Augustin, a master of detailed work on a small scale, may have further honed Berjon's meticulous approach to painting.

The Parisian art scene was dynamic. While David dominated with his Neoclassical canvases, other artists were exploring different paths. Flower painting, in particular, was enjoying a resurgence, partly due to the scientific interest in botany and the patronage of figures like Empress Josephine, who famously commissioned Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840), the "Raphael of Flowers," to document the roses in her gardens at Malmaison. Berjon operated within this milieu, distinguishing himself with his rich oil paintings, which contrasted with Redouté's delicate watercolors. He also would have been aware of the legacy of earlier French still life masters like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), whose quiet, intimate scenes set a high standard, and contemporary flower painters like Gerard van Spaendonck (1746-1822), a Dutch-born artist who became a professor of floral painting at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and was a significant influence on the genre.

Return to Lyon: Professor and Luminary of the Lyon School

In 1810, Berjon returned to his native Lyon, a city eager to reclaim one of its talented sons. His reputation preceded him, and he was appointed Professor of Flower Design (Professeur de la classe de la Fleur) at the newly established École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. This institution, founded in part due to Napoleon's initiatives to support industries vital to the French economy, aimed to train artists specifically for the local silk industry, known as "La Fabrique." Berjon's role was crucial: to elevate the aesthetic quality of silk designs by teaching students the art of floral representation.

As a professor, Berjon was influential. He established a "Salle des Fleurs" (Flower Room) within the school, a dedicated space where students could study fresh flowers and botanical illustrations. His teaching emphasized direct observation from nature, precision, and a deep understanding of plant forms. He aimed to instill in his students not just technical skill but also an appreciation for the beauty and variety of the floral world. Through his efforts, he became a central figure in what is known as the Lyon School of flower painting, a tradition that continued to flourish throughout the 19th century. His students and followers would carry on his legacy, ensuring Lyon remained a center for high-quality floral art and design.

His tenure at the École des Beaux-Arts, however, was not without its difficulties. Berjon was known for his somewhat difficult and uncompromising personality. After thirteen years, in 1823, he resigned from his professorship following disagreements with the school's administration. This event marked a turning point in his later career, leading him to a more reclusive existence.

Berjon's Artistic Style and Technique

Antoine Berjon's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous realism, vibrant yet harmonious color palettes, and sophisticated compositions. He worked primarily in oils, achieving a richness of texture and depth of color that set his work apart. His flowers are not merely decorative; they possess an almost tangible presence, rendered with botanical accuracy yet imbued with artistic vitality.

His deep understanding of botany, honed during his years as a textile designer, is evident in the precise rendering of each petal, leaf, and stem. He captured the delicate translucency of rose petals, the velvety texture of irises, and the intricate structures of complex blooms like peonies or tulips. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might idealize or stylize floral forms, Berjon often depicted flowers with a striking naturalism, sometimes including imperfections like a wilting leaf or an insect, details that recall the vanitas tradition of 17th-century Dutch masters such as Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684) or Willem Kalf (1619-1693).

Berjon's compositions are typically elegant and balanced, often featuring lush bouquets in simple vases or baskets, sometimes accompanied by fruit or other objects. He had a masterful command of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), using it to model forms, create depth, and highlight the textures of his subjects. His backgrounds are often dark and neutral, making the brightly lit flowers and fruit stand out dramatically, a technique also favored by Dutch masters like Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) and Jan van Huysum (1682–1749), whose works were highly sought after and influential across Europe.

While precision and realism were paramount, Berjon's work also shows an awareness of broader artistic currents. Some of his compositions exhibit a Neoclassical sense of order and clarity, while the richness of color and emotional intensity in others can hint at emerging Romantic sensibilities, seen in the works of artists like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) though Berjon's focus remained firmly within the still life genre. He managed to blend scientific observation with artistic sensibility, creating works that were both informative and aesthetically pleasing.

Representative Works and Important Exhibitions

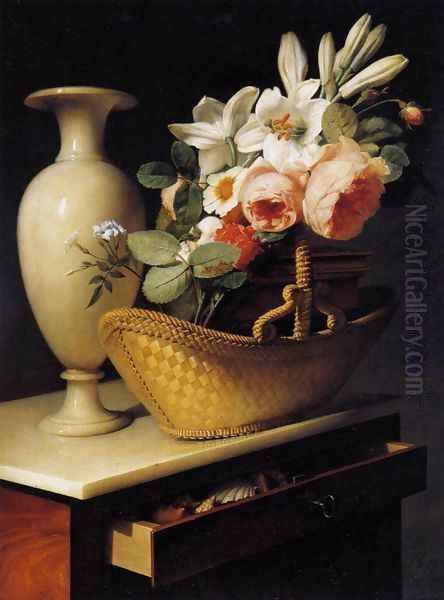

Antoine Berjon produced a significant body of work throughout his long career, with many of his paintings now held in prestigious museum collections. Among his most celebrated pieces is "Still Life with a Basket of Flowers" (Nature morte au panier de fleurs), often specifically identified as "Bouquet de lis et de roses dans une corbeille d'osier" (Bouquet of Lilies and Roses in a Wicker Basket), painted in 1814 and now in the collection of the Louvre Museum, Paris. This masterpiece showcases his exceptional skill: a profusion of lilies, roses, tulips, and other blooms spills from a wicker basket, each flower rendered with exquisite detail and vibrant color. The interplay of light on the petals and leaves creates a sense of depth and realism that is breathtaking. The composition is lush yet carefully arranged, demonstrating Berjon's mastery.

Another significant work often cited is "Still Life of Flowers, Grapes, and Peaches in a Basket with a Melon and a Glass of Wine on a Marble Ledge" (circa 1810-1819), which exemplifies his ability to combine various textures – the softness of petals, the bloom on grapes, the coolness of marble – into a harmonious whole. His "Still Life with Flower Arrangement and Fruit Basket" is another key example, demonstrating his typical arrangement of abundant, naturalistically depicted flora and fruit, often set against a dark background to enhance their luminosity.

Berjon exhibited frequently at the Paris Salon between 1791 and 1819, and later in Lyon. His works were acquired by collectors and public institutions. For instance, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon holds a significant collection of his paintings and drawings, reflecting his importance to the city's artistic heritage. These include works like "Fleurs dans une Corbeille d'osier sur un entablement de marbre" (Flowers in a Wicker Basket on a Marble Entablature) and studies that reveal his working process.

His participation in these exhibitions placed him in the company of other notable artists of the day. Beyond those already mentioned, the Salons would have featured works by landscape painters like Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714-1789, though mostly earlier, his influence persisted) and portraitists such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842). The competitive environment of the Salon spurred artists to produce their best work, and Berjon consistently met this challenge in his chosen genre.

Challenges, Later Years, and Anecdotes

Despite his artistic successes and his influential teaching position, Berjon's life was not without its challenges. His resignation from the École des Beaux-Arts in 1823, reportedly due to his "difficult character" and conflicts with the administration, marked a significant shift. He retreated into a more private life, continuing to paint and take on private students, but perhaps without the same public platform he once enjoyed.

It is recorded that in his later years, Berjon faced financial difficulties. Many of his paintings remained unsold at the time of his death. This situation was not uncommon for artists, even those of considerable talent, in an era where patronage could be fickle and the art market subject to economic fluctuations. His somewhat reclusive nature in his later years might also have contributed to this.

One interesting aspect of his career is the transition from an industrial designer for silks to a fine artist. This path was not unique in Lyon, where the boundaries between decorative and fine arts were often more fluid than elsewhere. His deep knowledge of flowers, essential for textile design, directly fed into his mastery as a flower painter. This practical grounding gave his work an authenticity and precision that was highly valued.

Another anecdote relates to his teaching. He was known to be a demanding instructor, insisting on rigorous observation and accuracy. His dedication to his students, however, was also recognized, and he played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of Lyonnais artists, including Simon Saint-Jean (1808–1860), who would become one of the most celebrated flower painters of the mid-19th century, effectively succeeding Berjon as the leader of the Lyon School.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Antoine Berjon passed away in Lyon in 1843 at the age of 89. While he may have faced financial struggles in his later years, his artistic legacy was secure. His contributions as a painter and teacher had a lasting impact, particularly on the Lyon School of flower painting, which continued to thrive, producing artists like Adolphe-Félix Cals (1810-1880), who also studied in Lyon, though was more known for landscapes and genre scenes later.

A few years after his death, a series of twenty-six of his floral compositions were published as lithographs by the firm Grobon Frères. This posthumous publication helped to disseminate his work to a wider audience and further solidify his reputation. These lithographs, along with his original paintings and drawings, are now prized items, with many held in the collections of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon and the Musée des Tissus (Museum of Textiles) in Lyon, underscoring his dual importance to both fine art and decorative design.

In the broader context of French art, Berjon is recognized as one of the foremost flower painters of the early 19th century. He successfully navigated the stylistic shifts from late Rococo through Neoclassicism and into the early stirrings of Romanticism, all while maintaining a distinctive personal style rooted in meticulous observation and technical brilliance. His work stands alongside that of other great still life and flower painters of his era, such as Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818), a prominent female artist who also excelled in floral still lifes and was a contemporary of Berjon's earlier Parisian period.

Today, Antoine Berjon's paintings are admired for their beauty, technical skill, and historical significance. They offer a window into the artistic preoccupations of his time and stand as a testament to the enduring appeal of floral art. His dedication to capturing the ephemeral beauty of flowers with such precision and artistry ensures his place among the masters of the genre. His influence extended through his students and helped to define a regional school of painting that celebrated the natural world with both scientific accuracy and profound aesthetic sensibility.