Antoine Chazal (1793–1854) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. Born and based in Paris throughout his life, Chazal was a remarkably versatile artist whose talents spanned a wide array of disciplines. He is perhaps best remembered for his exquisite flower paintings and detailed still lifes, but his oeuvre also encompassed portraiture, meticulous animal and human anatomical illustrations, delicate miniature painting, enamel work, and even designs for textiles. His career reflects the dynamic interplay between artistic tradition and the burgeoning scientific inquiries of his era, making him a fascinating subject for art historical exploration.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Antoine Chazal was born in Paris in 1793, a city then on the cusp of revolutionary change but already a long-established epicenter of European art and culture. Growing up in this vibrant environment undoubtedly provided him with unparalleled access to artistic influences and educational opportunities. The French capital was home to prestigious academies, bustling Salons, and a community of artists pushing the boundaries of various genres. It was within this milieu that Chazal's artistic inclinations were nurtured.

His formal training placed him under the tutelage of several distinguished masters, most notably Gérard van Spaendonck (1746–1822), a celebrated Dutch-born flower painter who had become a dominant figure in French botanical art. Van Spaendonck, a professor of floral painting at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) in Paris, was renowned for his scientifically accurate yet aesthetically stunning depictions of plants. His influence on Chazal was profound, instilling in him a deep appreciation for botanical accuracy, refined technique, and the delicate rendering of light and texture.

Another significant mentor for Chazal was Jan van Huysum (1682–1749), though this connection is more complex as van Huysum died long before Chazal's birth. It's more likely Chazal studied van Huysum's works extensively, as van Huysum was a towering figure of Dutch Golden Age flower painting, whose elaborate compositions and luminous colors were highly prized and emulated. Some sources also indicate a more direct, perhaps familial or workshop-based, connection to a later artist carrying the van Huysum legacy or name, or that Chazal worked closely with engravers who were masters of reproducing such styles. The provided information suggests Jan van Huysum was an assistant or collaborator on Flore Pittoresque, which would imply a contemporary figure, perhaps a descendant or an artist working in his style, rather than the historical master himself, unless it refers to Chazal and Spaendonck working from van Huysum's earlier designs or plates. For clarity, the primary, direct teacher was Gérard van Spaendonck, with the spirit and style of Jan van Huysum being a major guiding influence, likely through Spaendonck's own pedagogy and the study of original works or high-quality reproductions.

The Influence of Masters and Traditions

The tutelage under Gérard van Spaendonck was pivotal. Spaendonck was not merely a painter of pretty flowers; he was a botanist's artist, capable of capturing the precise morphology of a plant with an artist's eye for beauty. He succeeded Madeleine Françoise Basseporte as the official flower painter at the Jardin du Roi (later Jardin des Plantes), a position of considerable prestige. His students, including the famed Pierre-Joseph Redouté and, of course, Chazal, inherited this tradition of combining scientific rigor with artistic grace. Spaendonck's technique, often involving watercolor on vellum, emphasized delicate gradations of color and meticulous detail.

The broader influence of Dutch and Flemish still life traditions from the 17th and 18th centuries cannot be overstated in Chazal's development. Artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Rachel Ruysch, and the aforementioned Jan van Huysum had set an incredibly high standard for floral and fruit still lifes. Their works were characterized by opulent arrangements, rich colors, trompe-l'œil realism, and often, symbolic undertones (vanitas themes). This legacy was very much alive in early 19th-century France, and Chazal's work clearly shows an absorption of these principles, particularly in the careful rendering of textures – the velvety softness of petals, the waxy sheen of leaves, the cool smoothness of porcelain.

Furthermore, Chazal's artistic vision was shaped by the Spanish still life tradition, particularly the works of Luis Egidio Meléndez (1716–1780). Meléndez, though Spanish, spent time in Naples and was influenced by Italian naturalism. His still lifes are known for their stark realism, humble subjects (everyday foodstuffs and kitchenware), dramatic lighting, and palpable textures. This influence is evident in Chazal's ability to imbue simple objects, like a pumpkin, with a monumental presence and a sense of tangible reality. The emphasis on direct observation and unidealized representation found in Meléndez's work provided a counterpoint to the sometimes more decorative tendencies of French Rococo still life, as exemplified by artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, though Chardin himself was a master of profound realism.

A Flourishing Career: The Paris Salon and Official Recognition

Antoine Chazal established himself as a consistent and respected presence in the Parisian art world. Beginning in 1822, he became a regular exhibitor at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to display their work, gain critical attention, attract patrons, and build their reputations. Chazal continued to exhibit there almost annually until 1853, a testament to his sustained productivity and the consistent quality of his art.

His participation in the Salon would have brought his work to the attention of a wide audience, including critics, collectors, fellow artists, and the general public. The genres he specialized in – flower painting, still life, and portraiture – were all popular and well-represented at the Salon. Flower painting, in particular, enjoyed a resurgence in popularity in the post-Revolutionary period, valued for its decorative appeal, its connection to the natural world, and its display of technical skill. Artists like Anne Vallayer-Coster had already achieved significant success in this genre in the late 18th century.

Chazal's dedication and talent did not go unnoticed by the French state. In 1838, he was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), one of France's highest orders of merit. This prestigious award signified official recognition of his contributions to French art and culture and would have considerably enhanced his standing. It was an acknowledgment of his mastery and his role in upholding the esteemed traditions of French painting.

Mastery in Floral and Still Life Painting

Antoine Chazal's reputation largely rests on his exceptional skill in floral and still life painting. His works in these genres are characterized by their meticulous detail, vibrant yet harmonious color palettes, and sophisticated compositions. He possessed an acute observational ability, capturing the unique character of each flower, fruit, or object he depicted.

His floral paintings often showcase a variety of species, arranged in elegant bouquets or depicted as botanical studies. He masterfully rendered the delicate textures of petals, the subtle gradations of color, and the play of light on leaves and stems. These works are not mere copies of nature but carefully constructed artistic statements, balancing botanical accuracy with aesthetic appeal. He followed in the lineage of artists like Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer, whose grand floral arrangements adorned royal palaces in the 17th century, but Chazal's work often had a more intimate, scientifically informed quality, inherited from Spaendonck.

One of his most representative still life works is A Pumpkin (Un Potiron), painted in 1832. This painting exemplifies many of Chazal's stylistic hallmarks. The composition is simple yet powerful, with the large, textured pumpkin dominating the canvas. It is placed in a naturalistic setting, accompanied by small daisies, suggesting an outdoor scene or a harvest study. Chazal employs warm, direct lighting and a rich, earthy palette to give the pumpkin a remarkable sense of volume and tactility. The impasto technique, or the application of paint in thick, visible strokes, enhances the three-dimensional quality and the rough texture of the pumpkin's skin. This work demonstrates his debt to the realism of Meléndez and the Dutch tradition, while also possessing a distinctly French sensibility in its balance and subtle elegance.

His still lifes often featured fruits, vegetables, and sometimes game or tableware. In each case, he paid close attention to the interplay of light and shadow, the rendering of different surfaces, and the creation of a harmonious overall composition. His style was refined and detailed, avoiding excessive ostentation but always conveying a sense of the inherent beauty of the objects depicted.

Contributions to Scientific Illustration

Beyond his work for the Salon and private collectors, Antoine Chazal made significant contributions to the field of scientific illustration, a domain where art and science converge. This aspect of his career highlights his versatility and his ability to apply his artistic skills to rigorous, objective representation.

His most notable achievement in this area is arguably Flore Pittoresque, ou Recueil de Fruits et de Fleurs du Climat de Paris (Picturesque Flora, or Collection of Fruits and Flowers of the Paris Climate). This rare and valuable work, typically dated to the period of its creation and publication (sources vary, some suggesting around 1806-1810, others later, closer to 1818 or the 1820s, for Chazal's involvement), consisted of a series of exquisitely hand-colored plates. The provided information indicates it was a collaborative effort involving Chazal, his teacher Gérard van Spaendonck, and an assistant or collaborator named Jan van Huysum (again, likely a contemporary working in the style, or a reference to working from earlier models). These botanical plates were prized for their scientific accuracy and their artistic beauty, serving as important resources for botanists and horticulturalists, as well as being admired as works of art in their own right. The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation and Carnegie Mellon University are among the institutions that hold copies of this significant work.

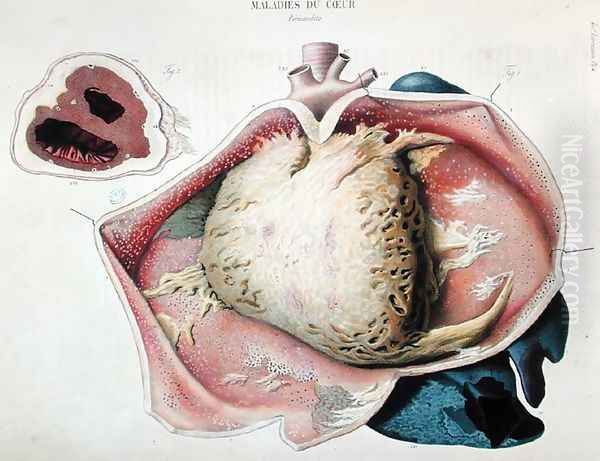

Chazal also applied his talents to anatomical illustration. He collaborated with the renowned French physician and pathologist Jean Cruveilhier (1791–1874) on his monumental work, Anatomie pathologique du corps humain (Pathological Anatomy of the Human Body), published in installments between 1829 and 1842. Chazal was responsible for many of the lithographic plates in this atlas, which became a foundational text in the study of pathology. His illustrations are remarkable for their clarity, precision, and often unsettling realism in depicting diseased organs and tissues. This work required not only exceptional draftsmanship but also a strong stomach and a scientific understanding of the subject matter. It placed him in the company of other artists who contributed to medical science, a tradition dating back to the Renaissance with figures like Leonardo da Vinci, and more contemporaneously, illustrators working for figures like Georges Cuvier, the great naturalist and comparative anatomist.

His involvement in scientific illustration underscores the close relationship between art and science in the 19th century. Artists like Chazal played a crucial role in disseminating scientific knowledge through their visual representations, long before the advent of photography as a common illustrative tool. His work in this field demanded a different kind of artistic intelligence – one focused on objective accuracy and clarity of information, yet still requiring immense skill and aesthetic judgment.

Beyond the Canvas: Miniatures, Enamel, and Design

Antoine Chazal's artistic repertoire extended beyond painting and scientific illustration. He was also proficient in miniature painting, a highly specialized art form requiring meticulous detail and a delicate touch. Miniatures, often portraits, were popular as intimate keepsakes and jewelry. His skill in rendering fine detail in his larger paintings would have translated well to this smaller scale.

He also worked with enamel, another demanding medium that involves fusing powdered glass to a substrate through firing. Enamel work can produce brilliant, jewel-like colors and durable surfaces, and was used for decorative objects, jewelry, and sometimes small plaques or portraits.

Furthermore, Chazal engaged in textile design. This field required an understanding of pattern, color harmony, and the technical requirements of fabric production. His experience with floral motifs and decorative composition in his paintings would have been valuable assets in creating designs for fabrics, perhaps for the burgeoning French textile industry, which included renowned centers like Lyon for silk. This breadth of practice was not uncommon for artists of earlier periods but became somewhat rarer as artistic specialization increased in the 19th century. It speaks to Chazal's adaptability and his wide-ranging artistic interests.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

Throughout his career, Antoine Chazal interacted and collaborated with various figures in the Parisian art and scientific communities. His collaboration with Jean Cruveilhier on the anatomical atlas is a prime example of his engagement with the scientific world.

In the artistic sphere, his relationship with his teachers, particularly Gérard van Spaendonck, was foundational. He also worked alongside his brother, André Chazal (1796–1860), who was an engraver. The similarity in their names and professions sometimes led to confusion in attributions of their works, a common issue for artistic families. André's skills as an engraver would have been crucial for reproducing artworks and illustrations for publication, a vital part of the art and science dissemination process of the era.

Chazal was also part of the broader Salon culture, which fostered interaction among artists. The provided information mentions his involvement in the 1817 Salon exhibition where he collaborated with Jean-François Van Dael (1764–1840), another prominent Franco-Flemish painter of flowers and fruit. Van Dael, like Spaendonck, was known for his refined technique and elegant compositions. Their collaboration reportedly involved a studio or painting course at the Sorbonne, which attracted many female students, indicating their role as educators as well. This connection highlights the collegial and sometimes collaborative nature of the Parisian art scene.

He also succeeded Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840) as the chief flower painter to Queen Marie-Amélie, wife of King Louis Philippe I. Redouté, often dubbed the "Raphael of Flowers," was perhaps the most famous botanical artist of his time, known for his exquisite watercolors of roses and lilies. To follow in Redouté's footsteps was a significant honor and a testament to Chazal's own eminence in the field of floral painting.

Other artists whose influence or contemporary presence would have been part of Chazal's world include Henriette Vincent, who also studied under Spaendonck and was known for her fruit and flower paintings, and later in the century, artists like Henri Fantin-Latour, who continued the tradition of exquisite floral still lifes with a more impressionistic touch.

Family Connections and Broader Legacy

Antoine Chazal's family background also presents some interesting connections. His great-grandfather, Antoine Toussaint de Chazal (1720–1802), was reportedly an amateur painter, suggesting an artistic inclination within the family lineage.

More famously, though indirectly, Chazal is connected to the post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). Antoine Chazal's son, Charles Chazal, was an artist and engraver. Charles's sister, Aline Chazal, married André Tristan Moscoso. Their daughter was Flora Tristan (1803–1844), a pioneering feminist writer, socialist activist, and author. Flora Tristan was Paul Gauguin's maternal grandmother. While Antoine Chazal and Paul Gauguin were not artistic contemporaries in the direct sense (Chazal died when Gauguin was a child), this familial link connects Chazal's lineage to one of the most revolutionary figures in modern art.

Artistic Style in Depth: A Synthesis of Traditions

Antoine Chazal's artistic style can be summarized as a sophisticated blend of meticulous realism, inherited from Dutch, Flemish, and Spanish still life traditions, and a refined French aesthetic sensibility. His works are characterized by:

1. Detailed Realism: He rendered objects with a high degree of accuracy, paying close attention to texture, form, and specific characteristics. This was particularly evident in his botanical and anatomical illustrations, but also in his still lifes.

2. Warm Lighting and Rich Color: Chazal often employed warm, direct light that illuminated his subjects effectively, creating a sense of depth and volume. His color palettes were rich and harmonious, capturing the vibrancy of flowers and fruits.

3. Tactile Quality: Through skillful brushwork, sometimes employing impasto, he gave his subjects a tangible, three-dimensional presence. One feels one could almost touch the objects in his paintings.

4. Balanced Compositions: While his subjects were rendered realistically, his compositions were carefully arranged for aesthetic harmony and visual appeal, reflecting classical principles of balance and order.

5. Versatility: He adapted his style to the demands of different genres, from the objective precision required for scientific illustration to the more expressive qualities suited for portraiture or decorative floral pieces.

His style reflects the broader trends in French art during the first half of the 19th century, a period that saw the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism and the rise of Realism. Chazal's work, with its emphasis on careful observation and faithful representation of nature, aligns with the burgeoning realist tendencies, yet it retains an elegance and refinement rooted in earlier traditions. He was less concerned with the dramatic or emotional subjects of Romanticism, focusing instead on the beauty and intricacy of the natural world and the human form.

Exhibition History and Market Reception

As noted, Antoine Chazal was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon from 1822 to 1853. This consistent presence ensured his work was seen and evaluated by the arbiters of taste and the art-buying public of his time. His paintings were acquired by private collectors and likely by state institutions as well, given his official recognition.

In the contemporary art market, works by Antoine Chazal continue to appear at auctions and in galleries. His paintings, particularly his floral still lifes and detailed fruit pieces like A Pumpkin, are appreciated for their technical skill and aesthetic charm. The rarity and historical significance of works like Flore Pittoresque mean that complete sets or individual plates can command high prices when they come to market. For instance, a copy of Flore Pittoresque sold at Christie's in London in 2017 for a significant sum (£133,000, as per one source), underscoring its value to collectors of botanical art and rare books. His anatomical illustrations, while perhaps less common on the open market, are also valued for their historical importance in the field of medical illustration.

The prices for his oil paintings vary depending on size, subject matter, condition, and provenance, but well-attributed and characteristic works are sought after by collectors specializing in 19th-century French art, still life, or botanical painting.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

Antoine Chazal was an artist of remarkable talent and versatility whose career bridged the worlds of fine art and scientific inquiry. As a student of Gérard van Spaendonck and an admirer of the great Dutch and Spanish still life masters, he developed a style characterized by meticulous detail, rich color, and a profound appreciation for the natural world. His contributions to floral painting, still life, portraiture, and particularly to botanical and anatomical illustration, mark him as a significant figure in 19th-century French art.

His regular participation in the Paris Salon and the prestigious Legion of Honour award attest to the recognition he received during his lifetime. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries like Delacroix or Ingres, who worked in grander historical or mythological genres, Chazal excelled in his chosen fields, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be admired for its beauty, precision, and historical importance. His art provides a valuable window into the artistic and scientific culture of his time, and his legacy endures in the collections of museums and private individuals who appreciate the enduring appeal of skillfully rendered nature and the human form. He remains a testament to the dedicated artist who finds profound beauty in the observable world and translates it with both scientific accuracy and artistic grace.