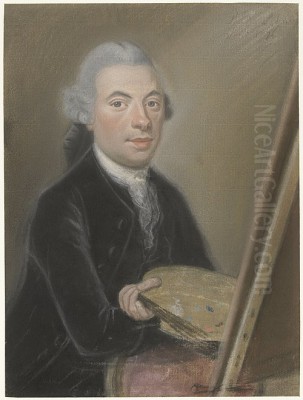

Jan van Os stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch art history, particularly celebrated for his mastery of still life painting during the latter half of the 18th century and the dawn of the 19th. Born in Middelharnis in 1744 and passing away in The Hague in 1808, Van Os navigated a period of transition in European art, yet remained deeply rooted in the meticulous traditions of the Dutch Golden Age, especially in the genre of flower and fruit painting. His work is characterized by exquisite detail, vibrant colour palettes, and compositions that speak to both the opulence of nature and the artistic sensibilities of his time.

As an artist working primarily in The Hague, Van Os became a pivotal link between the high Baroque masters of the previous century and the emerging tastes of a new era. He was not merely a painter but also a teacher, fostering a family dynasty of artists who would carry forward aspects of his style. His legacy endures through his breathtakingly detailed canvases, which continue to captivate audiences in museums and collections worldwide, offering a window into the enduring Dutch fascination with the beauty of the natural world captured through the artist's brush.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jan van Os's artistic journey began in the fertile ground of the Dutch artistic tradition. While born in Middelharnis, a town in South Holland, he pursued his formal artistic education in The Hague, a major centre for the arts in the Netherlands. His most significant mentor was Aert Schouman (1710-1792), a respected painter and draughtsman primarily known for his depictions of animals, particularly birds, often set within naturalistic environments.

Under Schouman's tutelage, Van Os would have honed his skills in detailed observation and precise rendering. Although Schouman's focus was zoological, the emphasis on capturing natural textures, forms, and the subtle play of light undoubtedly provided a strong foundation for Van Os's later specialization in floral and fruit still lifes. The meticulous attention required to depict feathers or the sheen of a bird's eye translated well to capturing the delicate petals of a flower or the dewy skin of a grape.

Van Os fully integrated into the artistic community of The Hague. A key milestone was his acceptance into the Confrerie Pictura, the city's prestigious guild for painters, sculptors, and artisans, in 1773. Membership in the guild was not only a mark of professional recognition but also provided opportunities for exhibition, commissions, and interaction with fellow artists, further shaping his career and reputation within the Dutch art world.

The Enduring Influence of Jan van Huysum

It is impossible to discuss Jan van Os without acknowledging the profound influence of Jan van Huysum (1682-1749), the undisputed master of Dutch flower painting in the generation preceding him. Van Huysum had revolutionized the genre with his lighter palettes, complex and often asymmetrical compositions, and an almost unparalleled level of detail that captured the very essence of each bloom and leaf. His works were highly sought after across Europe and set a standard that subsequent artists aspired to.

Jan van Os consciously followed in Van Huysum's footsteps, adopting many of his stylistic hallmarks. Like Van Huysum, Van Os favoured elaborate arrangements featuring a wide variety of flowers, often combining species that bloomed at different times of the year, creating idealized rather than strictly naturalistic bouquets. He also emulated Van Huysum's meticulous technique and his ability to render textures with astonishing realism, from the velvety softness of a rose petal to the cool smoothness of a marble ledge.

However, Van Os was not merely an imitator. While clearly indebted to Van Huysum, his works often possess a distinct character. Some critics note a slightly more robust quality in his arrangements, perhaps reflecting the changing tastes towards the end of the 18th century, which began to incorporate elements of Neoclassicism's clarity alongside Rococo elegance. His colour palette, while vibrant, could sometimes employ darker, richer backgrounds compared to Van Huysum's typically lighter settings, creating dramatic contrasts that highlighted the luminosity of the flowers and fruit.

Artistic Style and Meticulous Technique

Jan van Os's style is defined by its extraordinary realism and technical finesse. His primary goal was to create a convincing illusion of reality, capturing the intricate beauty of the natural world with painstaking accuracy. This involved an almost scientific level of observation, translating the specific characteristics of each flower, fruit, leaf, and even insect onto the canvas. The botanical accuracy in his paintings is often remarkable, allowing viewers to identify individual species with ease.

His technique was perfectly suited to this aim. He employed fine brushes and likely worked with glazes – thin, transparent layers of paint – to achieve smooth transitions of colour and tone, creating depth and luminosity. This meticulous approach allowed him to render the most subtle details: the delicate veining on a leaf, the powdery bloom on a grape, the iridescent shimmer of a butterfly's wing, or the tiny droplets of dew clinging to a petal. The surfaces in his paintings often appear flawless, with little evidence of brushwork, enhancing the illusionistic effect.

Compositionally, Van Os often favoured arrangements that were abundant and dynamic. While sometimes employing the pyramidal structure common in still life, his bouquets frequently cascade and overflow their containers, creating a sense of luxurious profusion. He masterfully balanced complex groupings of objects, ensuring that despite the wealth of detail, the overall composition remained harmonious and visually engaging. The interplay of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) was crucial, used to model forms, create depth, and highlight key elements within the arrangement, drawing the viewer's eye through the scene.

Key Themes and Recurring Motifs

The subjects of Jan van Os's paintings are primarily drawn from the natural world, focusing on flowers and fruits arranged artfully, often accompanied by other elements. His floral compositions showcase a dazzling variety of species, including roses, tulips, peonies, poppies, carnations, irises, morning glories, and many others. These were often luxury items, reflecting the horticultural interests and wealth of the patrons who commissioned such works. The arrangements frequently seem to defy seasons, presenting a Utopian vision of perpetual bloom.

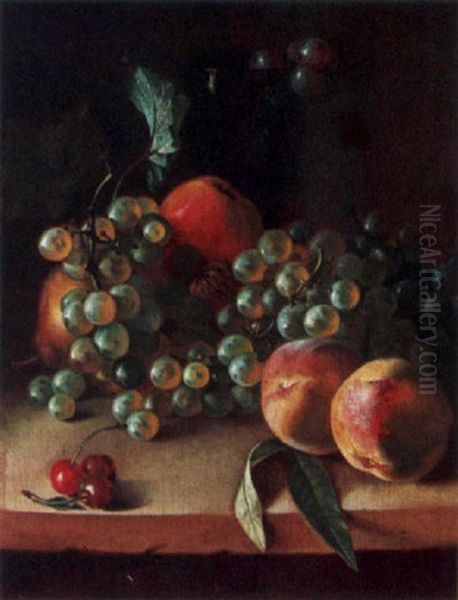

Fruits are depicted with equal verisimilitude: plump grapes (both green and purple), fuzzy peaches, smooth plums, ripe figs, and sometimes more exotic items like melons or pomegranates. These are often shown spilling over ledges or nestled amongst the flowers, adding variety in form, colour, and texture. The sensuous appeal of the fruit – suggesting taste and abundance – complements the visual beauty of the flowers.

A characteristic feature of Van Os's work, inherited from the Dutch still-life tradition, is the inclusion of small creatures. Insects like butterflies, caterpillars, flies, beetles, ants, and snails often populate his scenes. These were not mere decorative additions; they added another layer of realism and often carried symbolic weight, alluding to the theme of vanitas – the transience of life and earthly beauty. The perfect bloom would eventually fade, the ripe fruit would decay, and the insect's life was fleeting. Occasionally, a bird's nest with eggs, perhaps a nod to his teacher Aert Schouman, might appear, symbolizing life, fragility, and the cycles of nature. The settings often include classical elements like terracotta vases or urns and cool marble ledges, adding a sense of timelessness and grounding the ephemeral beauty of the organic elements.

Representative Works

Several key works exemplify Jan van Os's style and mastery. His Fruit and Flowers on a Marble Ledge, housed in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, is a quintessential example. It features a lavish bouquet in an ornate terracotta vase alongside a profusion of fruit—grapes, peaches, plums—arranged on a cool marble surface. The composition is rich and complex, filled with intricate detail, from the delicate rendering of each flower petal to the realistic depiction of insects like a butterfly and a fly. The play of light across the different textures is masterfully handled.

Another significant work is Flowers and Fruit in a Terracotta Vase, held by the National Gallery in London. This painting showcases a similarly opulent arrangement, demonstrating Van Os's skill in creating vibrant, harmonious compositions bursting with life. The variety of flowers, the realistic portrayal of fruit including a cut melon revealing its seeds, and the presence of insects contribute to the painting's richness and illusionistic quality. The terracotta vase itself is rendered with attention to its texture and classical form.

His painting Flowers and Fruit dated 1774, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, France, further attests to his capabilities early in his mature career. Such works highlight his consistent ability to blend meticulous detail with dynamic composition. While titles like Still Life with Flowers and Fruit are common due to the nature of his oeuvre, each painting offers a unique combination of elements, showcasing his endless fascination with the variety and beauty of nature, rendered with exceptional technical skill. These works cemented his reputation both domestically and internationally.

Beyond Still Life: Forays into Landscape

While Jan van Os is overwhelmingly celebrated for his exquisite still life paintings, his artistic output was not solely confined to this genre. Particularly earlier in his career, he also engaged with landscape painting, another strong tradition within Dutch art. Although fewer examples of his landscapes survive or are as widely known, their existence points to a broader artistic interest and technical versatility.

His landscape works likely drew upon the established Dutch conventions for depicting the local scenery, possibly featuring pastoral views, river scenes, or wooded areas. The skills honed in landscape – observing the effects of light on different surfaces, rendering foliage, and creating atmospheric perspective – would have undoubtedly informed his still life practice as well. Capturing the nuances of a leaf or the texture of bark in a landscape setting shares common ground with detailing the elements within a floral arrangement.

However, the market demand and perhaps his own inclination led him to specialize increasingly in the highly popular and lucrative genre of flower and fruit painting. It was in this domain that he achieved his greatest fame and made his most lasting contribution to art history. His landscapes remain a footnote to his career, but they underscore his comprehensive training and abilities as a painter grounded in the diverse traditions of Dutch art.

The Van Os Artistic Dynasty

Jan van Os was not only a successful artist in his own right but also the patriarch of a notable artistic family. He passed on his skills and passion for painting to his children, several of whom became accomplished artists themselves, ensuring the Van Os name continued to be associated with Dutch art into the 19th century. This familial transmission of artistic knowledge was a common practice in earlier centuries.

His eldest son, Pieter Gerard van Os (1776-1839), initially trained by his father, became particularly known for his landscapes with cattle, aligning himself with the enduring Dutch tradition of pastoral scenes reminiscent of artists like Paulus Potter (1625-1654). While diverging from his father's primary focus, Pieter Gerard achieved considerable success and recognition.

Another son, Georgius Jacobus Johannes van Os (1782-1861), followed more closely in his father's footsteps, specializing in flower and fruit still lifes. He worked for a time at the Sèvres porcelain factory near Paris, designing decorations, which reflects the high level of detail and decorative quality inherent in his training. His style, while clearly influenced by his father, evolved to reflect early 19th-century tastes.

Jan van Os's daughter, Maria Margaretha van Os (1779-1862), also became a painter, specializing, like her father and brother Georgius, in still lifes of flowers and fruit. She exhibited her work in Amsterdam and The Hague, gaining recognition as a skilled artist in a field still largely dominated by men. The success of his children testifies to Jan van Os's effectiveness as a teacher and the strength of the artistic environment he fostered within his family. Other prominent Dutch artists like Willem van Leen (1753-1825) were also among his pupils, further extending his influence.

Contemporaries and the Wider Artistic Context

Jan van Os worked during a period that saw the continuation of established traditions alongside the stirrings of new artistic movements across Europe. Within the Netherlands, the legacy of the 17th-century Golden Age still loomed large. Artists continued to specialize in genres like still life, landscape, and portraiture, though perhaps without the same level of groundbreaking innovation as their predecessors like Rembrandt (1606-1669) or Vermeer (1632-1675).

In the realm of still life, Van Os was undoubtedly the leading figure of his generation in the Northern Netherlands, carrying forward the tradition of detailed realism exemplified by Jan van Huysum and earlier masters like Willem Kalf (1619-1693), Willem van Aelst (1627-1683), and the pioneering female flower painter Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750). He can also be seen in the lineage extending back to the earliest specialists in flower painting, such as Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621) and Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94-1657).

His Dutch contemporaries included artists like the brothers Jacob van Strij (1756-1815) and Abraham van Strij (1753-1826), who were known for landscapes and genre scenes, often looking back to 17th-century models. Internationally, the context included prominent still life painters in other countries. In France, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779) had brought a different, more intimate and textural approach to still life earlier in the century. Closer in time and subject matter was Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818), a direct contemporary of Van Os admitted to the French Royal Academy, who also specialized in rich floral and still life compositions, reflecting the parallel development of the genre under Rococo and emerging Neoclassical influences in France.

International Recognition and Market Appeal

Jan van Os's talent did not go unnoticed beyond the borders of the Netherlands. His works found considerable favour internationally, particularly in England and France, where discerning collectors appreciated his technical brilliance and the decorative appeal of his compositions. The meticulous detail and vibrant realism of his paintings catered to the tastes of an affluent clientele who sought luxury goods and art that reflected refinement and an appreciation for nature's beauty.

He actively sought recognition abroad, notably by exhibiting his works in London. Records show his participation in exhibitions organized by the Society of Artists of Great Britain. His submissions were well-received, with one critic in 1777 praising his work highly, which helped solidify his reputation among British connoisseurs and patrons. This international exposure was crucial for an artist seeking wider fame and financial success during this period.

The acquisition of his paintings by foreign collectors, including members of the aristocracy, meant that his works entered significant collections across Europe. This not only enhanced his personal prestige but also contributed to the ongoing appreciation and influence of the Dutch still-life tradition abroad. The presence of his works today in major international museums, such as the National Gallery in London and the Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, is a testament to this widespread appeal and enduring recognition.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Jan van Os left a significant mark on the history of Dutch art, primarily as one of the last great exponents of the highly detailed floral and fruit still life tradition that had flourished since the Golden Age. He successfully adapted the meticulous style of Jan van Huysum for a late 18th-century audience, maintaining an exceptionally high level of technical skill and botanical accuracy. His works represent a culmination of this specific genre before artistic tastes shifted more decisively towards Neoclassicism and later Romanticism in the 19th century.

His influence extended directly through his role as a teacher, particularly to his own children, who carried the family's artistic reputation into the next generation. Georgius Jacobus Johannes and Maria Margaretha continued to work in the still life genre, adapting their father's style to contemporary sensibilities, while Pieter Gerard found success in landscape painting. This familial dynasty helped perpetuate the traditions of Dutch painting.

Today, Jan van Os is remembered for his technical virtuosity, his vibrant compositions, and his dedication to capturing the beauty of the natural world with unparalleled precision. His paintings are prized possessions of major museums and private collections worldwide. They continue to be studied for their technique and admired for their aesthetic qualities, offering a lasting testament to the enduring appeal of Dutch still life and the talent of one of its late masters. His work serves as a bridge, connecting the opulent traditions of the past with the changing artistic landscape of his time.

Conclusion: A Master of Detail and Decoration

Jan van Os occupies a respected place in the annals of European art history as a master of Dutch still life painting. Working in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, he inherited a rich artistic tradition, particularly the legacy of Jan van Huysum, and infused it with his own meticulous skill and sensibility. His paintings of flowers and fruit are celebrated for their astonishing realism, vibrant colours, complex compositions, and flawless technique. They represent a peak of achievement in a genre deeply embedded in Dutch culture.

Beyond his technical prowess, Van Os's work reflects the era's appreciation for nature, scientific observation, and decorative elegance. His success both domestically and internationally, coupled with his role in fostering an artistic dynasty through his children, underscores his significance. While artistic styles evolved after his time, the sheer beauty and technical brilliance of Jan van Os's paintings ensure their enduring appeal, securing his legacy as a key figure in the later chapters of Dutch still life painting. His canvases continue to enchant viewers, offering intricate, idealized visions of nature's bounty captured with the brush of a true master.