Arthur Clifton Goodwin stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of American art at the turn of the twentieth century. An artist largely self-taught, he rose to prominence through his evocative depictions of Boston, capturing its streets, waterfronts, and iconic landmarks with a style that uniquely blended the atmospheric concerns of Impressionism with the urban focus of the Ashcan School. Despite achieving considerable recognition and attracting esteemed patrons, Goodwin's life was marked by personal turmoil and a bohemian existence that ultimately contributed to his premature death. His legacy resides in a body of work that offers a vibrant, light-filled, yet often gritty portrayal of a city undergoing transformation.

Early Life and Unconventional Beginnings

Arthur Clifton Goodwin was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, likely in 1866, although some sources cite 1864. He spent his formative years in the nearby city of Chelsea, Massachusetts, just across the Mystic River from Boston. Unlike many of his contemporaries who pursued formal academic training in the United States or Europe, Goodwin came to painting relatively late in life, around the age of thirty. He possessed no formal art education, instead embarking on a path of self-discovery as a painter.

His initial inspiration is said to have come from observing the work of his friend, the artist Louis Kronberg. Kronberg, known for his paintings and pastels of dancers and theatrical scenes, and who had connections with French artists like Edgar Degas, may have provided an early glimpse into the possibilities of capturing modern life through art. Around 1900, Goodwin began to dedicate himself seriously to painting, quickly developing a distinctive approach centered on the city that would become his primary muse: Boston.

Forging a Style: American Impressionism Meets Urban Reality

Goodwin emerged as an artist during a period when American Impressionism was flourishing, particularly in Boston. Artists like Childe Hassam, Frank Weston Benson, and Edmund C. Tarbell were adapting the French Impressionist preoccupation with light, color, and broken brushwork to American subjects. Goodwin absorbed these influences, becoming adept at capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, the subtle shifts in color according to the time of day or weather conditions, and the overall sensory experience of a place.

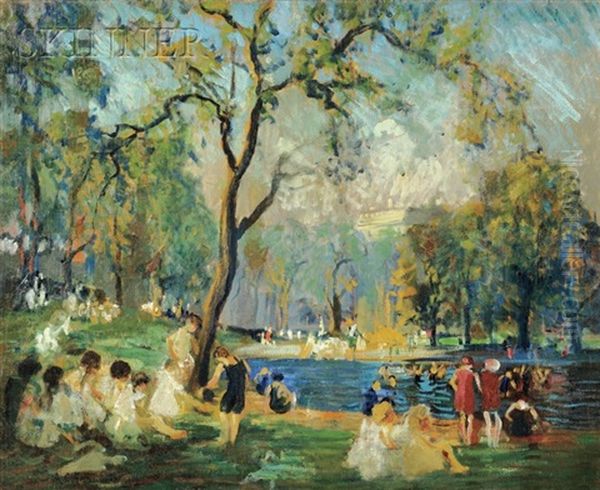

However, Goodwin's work diverged from the often more genteel subjects favored by some Boston Impressionists, such as elegant interiors or sun-dappled landscapes. His focus remained steadfastly on the urban environment – the bustling docks, the shadowed streets, the imposing architecture, the flow of city life. This thematic interest aligned him spiritually, if not always stylistically, with the Ashcan School, a movement centered in New York and spearheaded by Robert Henri. Artists like John Sloan, George Luks, and George Bellows aimed to depict the unvarnished reality of modern urban existence.

Goodwin shared their interest in the everyday fabric of the city, but he rendered it through a more distinctly Impressionistic lens. His paintings rarely delve into the overt social commentary found in some Ashcan works. Instead, they celebrate the visual poetry of the urban scene, finding beauty in the interplay of light on brick facades, the reflections in wet streets, or the silhouettes of ships against the harbor sky. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to harmonize the human element with the natural and built environment.

Boston as Muse: Landmarks and Waterfronts

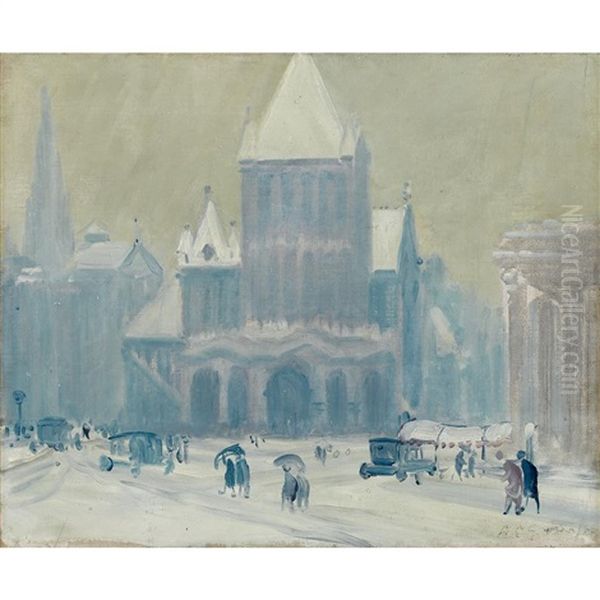

Boston provided Goodwin with an inexhaustible supply of subjects. He painted its famous landmarks, its busy thoroughfares, and its vital waterfront with equal enthusiasm. The Massachusetts State House, with its iconic golden dome, appears frequently in his work, captured from various angles and under different atmospheric conditions. He painted views of Beacon Hill, the Boston Common, and Copley Square, often focusing on the way sunlight or snowfall transformed familiar scenes.

One of his most celebrated subjects was Park Street Church, standing prominently at the corner of Tremont and Park Streets. His depictions of this historic structure, such as Park Street Church, Boston, showcase his skill in rendering architecture not just as static form, but as a surface receptive to the play of light and shadow, integrated into the surrounding urban activity. He captured the church in different seasons, highlighting its enduring presence amidst the changing city.

Goodwin was particularly drawn to Boston's waterfront, especially the area around T Wharf. This bustling commercial hub, located on Atlantic Avenue, was a docking point for fishing vessels, including many belonging to the city's Portuguese and Italian communities. His "T Wharf" series is perhaps his most distinctive contribution. These paintings, often executed in oil or pastel, capture the lively atmosphere of the docks – the jumble of masts and rigging, the reflections of boats in the water, the figures of fishermen and dockworkers. Works like T Wharf (numerous versions exist) are notable for their vibrant color, energetic brushwork, and palpable sense of place. They convey the maritime heart of the city with authenticity and visual flair.

Technique and Medium: Capturing Atmosphere

Goodwin worked proficiently in both oil paint and pastel. His oil paintings often feature vigorous, textured brushwork, applying paint in dabs and strokes that coalesce into a coherent image when viewed from a distance, a hallmark of Impressionist technique. His palette could range from bright and high-keyed, especially in sunny or snowy scenes, to more muted and tonal, particularly in depictions of overcast days or twilight views.

His pastels are equally accomplished, demonstrating a masterful handling of the medium to achieve effects of light, texture, and atmosphere. Pastel allowed for a directness and immediacy, enabling him to quickly capture fleeting moments of urban life. Whether working in oil or pastel, Goodwin's primary concern was often the accurate rendering of light and its effect on color and form. He excelled at depicting different weather conditions – the crisp clarity of a winter day, the hazy humidity of summer, the damp sheen of rain-slicked streets. His works convey not just the look of the city, but its feel.

The Boston Art World: Connections and Recognition

Despite his lack of formal training, Goodwin gained acceptance within the Boston art establishment. He became a member of the prestigious Guild of Boston Artists in 1914 and also belonged to the Boston Art Club and the Boston Society of Water Color Painters. He exhibited his work regularly at prominent venues, including the Guild, the Boston Art Club, Doll & Richards Gallery, and occasionally further afield, such as at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His work was shown at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, indicating his standing in the city's art scene.

He moved in circles that included established artists and influential patrons. His talent was recognized early on by figures of considerable stature. The renowned portraitist John Singer Sargent, a towering figure in the art world with strong Boston connections, admired and purchased Goodwin's work. Isabella Stewart Gardner, the formidable collector and creator of the Fenway Court museum, also acquired his paintings, as did the prominent collector John T. Spaulding. Such endorsements from key tastemakers significantly bolstered his reputation.

While self-taught, he was certainly aware of and engaged with the work of his contemporaries. He would have known the paintings of fellow Boston Impressionists like Childe Hassam, whose depictions of Boston Common offer an interesting comparison to Goodwin's own city views. He likely interacted with other artists associated with the Guild and the Boston Art Club, potentially including figures like Maurice Prendergast, another Boston artist known for his unique Post-Impressionist style and scenes of urban leisure, or perhaps marine painters like Charles H. Woodbury.

A Life of Contrasts: Talent and Turmoil

Goodwin's artistic success unfolded against a backdrop of personal instability. He cultivated a bohemian persona and was apparently known for his dapper dress, earning him the nickname "Beau Brummel of Chelsea." However, this lifestyle was coupled with a serious struggle with alcoholism. His drinking habits often led to financial difficulties, strained relationships, and an erratic existence. He was known to be unreliable, frequently in debt, and his personal life, including his marriage, suffered as a result.

This turbulent lifestyle inevitably impacted his career. While patrons like Sargent and Gardner recognized his talent, his unreliability likely cost him other opportunities and may have hindered the broader development of his career. There's a sense of potential not fully realized due to the persistent challenges of his personal life. His story echoes that of other talented artists whose lives were complicated by addiction or instability, adding a layer of tragedy to his artistic achievements.

The end of Goodwin's life was abrupt and poignant. In 1929, at the age of approximately 63 or 65, he died in his room at the Hotel Hemenway in Boston (some accounts say his studio or a gallery), the cause attributed to the effects of excessive alcohol consumption. Reportedly, he had been planning a trip to Paris, perhaps to finally experience firsthand the roots of the Impressionist movement that had so influenced his work, but this ambition remained unfulfilled.

Legacy and Influence

Arthur Clifton Goodwin left behind a significant body of work that secures his place as one of Boston's most important early 20th-century painters. He was a gifted observer and a skilled technician who developed a personal style that bridged American Impressionism and the urban realism of the Ashcan School. His paintings offer an invaluable visual record of Boston during a period of growth and change, capturing both its iconic landmarks and the texture of its everyday life, particularly along its vital waterfront.

His influence is perhaps less direct than that of major teachers like Robert Henri, but his work stands as a testament to the vitality of Impressionist techniques when applied to the American urban scene. He demonstrated that the city itself, with its complex interplay of architecture, nature, and human activity, could be a compelling subject for artists focused on light and atmosphere. His paintings resonate with later depictions of the American city by artists such as Edward Hopper or Ernest Lawson, even if their styles differed, sharing an interest in capturing the specific character of urban spaces.

Today, Goodwin's works are held in the collections of numerous museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Colby College Museum of Art, and various private and club collections like the Union Club of Boston and the St. Botolph Club. His paintings continue to be admired for their atmospheric beauty, their energetic execution, and their affectionate yet unsentimental portrayal of Boston. He remains a compelling figure, an artist whose considerable talent shone brightly despite the shadows cast by his troubled life.

Conclusion

Arthur Clifton Goodwin's contribution to American art lies in his distinctive vision of the urban landscape. As a largely self-taught painter, he navigated the currents of American Impressionism and the Ashcan School to create a style uniquely his own. His paintings of Boston, particularly his vibrant depictions of T Wharf and his atmospheric renderings of the city's streets and landmarks under varying conditions of light and weather, remain his most enduring legacy. While his life was marked by instability and ended tragically, his art offers a lasting and evocative portrait of a city, captured with a sensitivity to light, color, and place that continues to engage viewers today. He stands as a significant chronicler of Boston and a noteworthy, if complex, figure in the history of American painting.