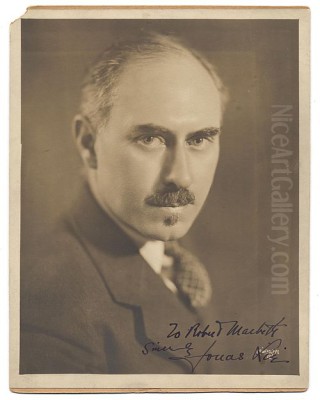

Jonas Lie stands as a significant figure in early twentieth-century American art, a painter whose life and work bridged the cultural landscapes of his native Norway and his adopted United States. Born into a period of artistic transition, Lie forged a distinctive style that blended the vibrant light and color of European Impressionism with the burgeoning energy and raw realism of American life. His canvases captured the dynamism of New York City, the rugged beauty of the New England coast, and the monumental scale of modern engineering, leaving behind a legacy of visually striking and emotionally resonant works.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jonas Lie was born on April 29, 1880, in Moss, Norway, a coastal town near Oslo. His heritage was a blend of Norwegian and American roots; his father, Sverre Lie, was a Norwegian civil engineer, and his mother, Helen Augusta Steele, hailed from Hartford, Connecticut. This dual background would subtly inform his artistic perspective throughout his career. Tragedy struck early when his father died, prompting the young Jonas, at the age of twelve (around 1892), to be sent to Paris to live with his uncle, the celebrated Norwegian novelist Jonas Lie, and his aunt, Thomasine Lie.

This period in Paris, though relatively brief, was culturally formative. Living in the household of a literary giant exposed him to a vibrant circle of Scandinavian expatriates and intellectuals. It's documented that he encountered luminaries such as the playwright Henrik Ibsen, the writer Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, and the composer Edvard Grieg. This immersion in a rich artistic milieu undoubtedly broadened his horizons and perhaps planted the seeds of his own creative ambitions.

Following his aunt's death, Lie immigrated to the United States in 1893, settling in New York City. His early years in America were marked by practical necessity. To support himself, he took a demanding job as a fabric designer at a cotton mill in Plainfield, New Jersey. He worked there for nine years, a testament to his resilience and determination. Crucially, however, he did not abandon his artistic aspirations. During these years, he dedicated his evenings to studying art, attending classes at institutions like the National Academy of Design, the Art Students League of New York, and possibly the Cooper Union or the City College of New York. This period of working by day and studying by night laid the foundation for his professional art career.

Development of Style: Impressionism Meets American Reality

Jonas Lie's artistic style evolved from a confluence of influences, most notably European Impressionism and the specific realities of his American environment. He deeply admired the French Impressionists, particularly Claude Monet, whose sensitivity to light and atmospheric effects resonated with Lie's own inclinations. The influence of fellow Norwegian Frits Thaulow, known for his evocative depictions of water and snow, is also clearly discernible in Lie's treatment of reflective surfaces and winter landscapes. Lie adopted the Impressionist emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, utilizing broken brushwork and a bright, often high-keyed palette to convey the vibrancy of light.

However, Lie was not merely an imitator of European trends. He adapted Impressionist techniques to distinctly American subjects. Living and working in New York City, he absorbed the energy and dynamism of the modern metropolis. While not formally a member of the Ashcan School, his work shares affinities with painters like Robert Henri, George Bellows, John Sloan, George Luks, and William Glackens. Like them, he was drawn to the urban spectacle – the bustling harbors, the towering structures, the everyday life unfolding against the city backdrop. He brought an Impressionist's eye for light and color to subjects often associated with the more gritty realism of the Ashcan artists.

His unique synthesis involved applying this vibrant, light-filled approach to the industrial and urban landscapes of America. He didn't shy away from depicting the man-made world but often imbued it with a sense of atmospheric beauty. His brushwork could be bold and vigorous, building up textures that conveyed the solidity of architecture or the fluidity of water. This fusion of European technique and American subject matter allowed him to create paintings that felt both modern and deeply rooted in observation. Other American Impressionists like Childe Hassam or J. Alden Weir also depicted American scenes, but Lie often brought a particular dynamism and focus on the interplay between nature and industry that set his work apart.

Iconic Themes: The City, The Coast, The Canal

Jonas Lie's oeuvre is often characterized by his recurring engagement with three major themes: the urban landscape of New York City, the maritime environment of the New England coast, and the monumental undertaking of the Panama Canal construction.

New York Cityscapes

New York City provided Lie with an endless source of inspiration. He was captivated by its verticality, its energy, and the interplay of light on its structures and waterways. He painted its bridges, particularly the Brooklyn Bridge, numerous times, exploring them from different angles and under varying atmospheric conditions. His harbors teemed with tugboats and ships, smoke billowing from stacks, light reflecting off the water. Unlike some Impressionists who focused on parks or genteel street scenes, Lie often embraced the industrial aspects of the city's waterfront.

His celebrated work, Morning on the River (c. 1911-12), exemplifies his approach. It depicts the East River and the Brooklyn Bridge on a cold winter morning. Rather than a distant, picturesque panorama, the viewpoint feels closer, perhaps from the docks, emphasizing the powerful forms of the bridge's piers and the activity of the tugboats. The painting masterfully captures the chill air and the specific quality of winter light reflecting off icy surfaces and frozen clouds. It showcases his ability to combine strong architectural composition with sensitive atmospheric rendering, finding beauty in the industrial pulse of the city. His cityscapes stand alongside those of contemporaries like Childe Hassam, but often possess a more robust, energetic quality.

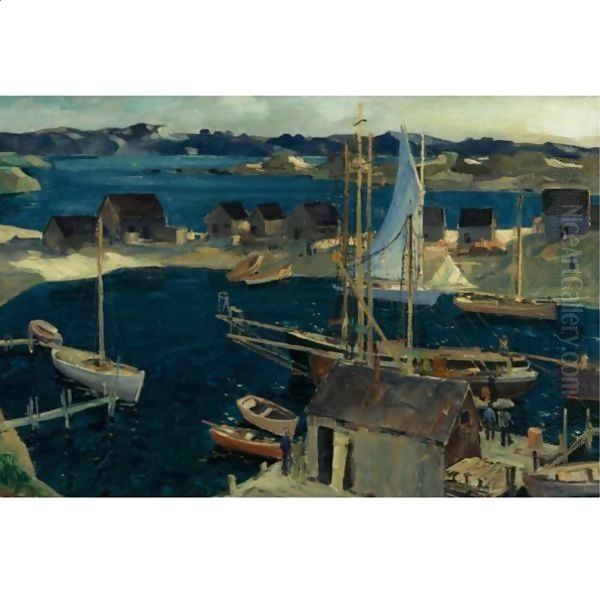

New England Coast

Complementing his urban scenes, Lie frequently sought refuge and inspiration along the coasts of New England, particularly Maine and Massachusetts. He was drawn to the rugged shorelines, the fishing villages, the interplay of sea and sky, and the sturdy character of maritime life. His coastal paintings often feature fishing boats (sloops and schooners), docks, and the powerful Atlantic surf crashing against rocks. He excelled at capturing the changing moods of the sea, from tranquil, sunlit harbors to dramatic, storm-tossed waves.

In works depicting the coast, Lie employed his characteristic vibrant palette and dynamic brushwork to convey the elemental forces of nature. He captured the sparkle of sunlight on water, the deep blues and greens of the ocean, and the weathered textures of boats and coastal structures. These paintings resonate with the tradition of American maritime art, evoking comparisons to Winslow Homer in their appreciation for the power of the sea, though Lie's approach remained distinctly Impressionistic in its handling of light and color. He found a balance between depicting the specific character of a place and conveying a more universal sense of nature's grandeur.

The Panama Canal Series

In 1913, Jonas Lie undertook a significant journey to Panama to witness and document the final stages of the Panama Canal's construction. This massive engineering project, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, was a symbol of American ingenuity and ambition. Lie spent several months there, creating a remarkable series of paintings that captured the immense scale, the human labor, and the dramatic landscape transformations involved in the canal's creation.

His Panama Canal paintings, sometimes referred to collectively or by individual titles like The Conquerors, depict the giant locks, the deep cuts through the earth (like the Culebra Cut), the powerful machinery, and the workers dwarfed by the scale of their undertaking. He used his bold compositions and rich color to convey the almost overwhelming power of both the engineering and the tropical environment. These works are not just documentary records; they are dramatic interpretations of a pivotal moment in modern history, exploring themes of human endeavor, technological might, and the reshaping of nature. Lie later donated a significant group of these paintings to the United States Military Academy at West Point, in honor of Colonel George W. Goethals, the chief engineer of the canal project. This series significantly boosted Lie's national reputation and remains one of his most recognized achievements.

Recognition and Professional Life

Jonas Lie achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His talent was acknowledged early on, winning a silver medal at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World's Fair) in 1904. He consistently exhibited his work at major venues, including the prestigious National Academy of Design, where he would later hold a prominent position. He received various awards from the Academy over the years, potentially including the Hallgarten Prize, which supported younger artists.

His participation in the landmark 1913 Armory Show (the International Exhibition of Modern Art) placed him amidst the currents of modernism, although his work remained more rooted in Impressionism and Realism compared to the European avant-garde showcased there, which included artists like Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Constantin Brancusi. The Armory Show was a pivotal event in American art history, exposing American audiences and artists to radical new styles. Lie's inclusion demonstrated his relevance within the contemporary art scene. Some sources also suggest his work was exhibited as part of the art competitions held during the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, a practice common in that era.

Lie was actively involved in the organizational life of the art world. He was a founding member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), the group responsible for organizing the Armory Show. Perhaps his most significant institutional role was his presidency of the National Academy of Design, a position he held from 1934 to 1939. Leading the NAD during the challenging years of the Great Depression required considerable administrative skill and diplomacy. His tenure saw the Academy navigate economic hardship and evolving artistic tastes.

His leadership period was not without controversy. In 1934, he reportedly expressed sympathy for the destruction of Diego Rivera's mural Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Center, a statement that sparked debate within the art community about artistic freedom and property rights. Regardless of this incident, his presidency marked a significant period of service to a major American art institution. His contributions were recognized internationally when, in 1932, King Haakon VII of Norway made him a Knight of the Order of St. Olav for his achievements in art.

Artistic Relationships and Context

While specific records of direct, sustained collaborations with other painters are scarce, Jonas Lie was certainly an active participant in the American art community. His stylistic affinities connected him to the broader circle of American Impressionists, artists like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and Theodore Robinson, who adapted French Impressionist principles to American landscapes and cityscapes. His interest in urban and industrial themes also placed him in dialogue with the Ashcan School artists like Robert Henri and George Bellows, even if his technique differed.

His role within the National Academy of Design placed him in contact with the more established, traditional wing of the art world, interacting with figures who might have included painters like Kenyon Cox or sculptors like Daniel Chester French. As president, he would have engaged with a wide spectrum of artists affiliated with the Academy.

The mention of Lie potentially providing illustrations for fairy tales hints at a connection, perhaps thematic or inspirational, to the rich tradition of Scandinavian illustration, exemplified by artists like Norway's Theodor Kittelsen and Erik Werenskiold, or Denmark's Thorvald Bindesbøll and August Jerndorff. While not collaborators in the modern sense, Lie's Norwegian heritage and his likely familiarity with these traditions might have informed aspects of his work or his broader cultural interests. His primary sphere of interaction, however, remained the American art scene, where he navigated the currents between Impressionism, Realism, and the burgeoning forces of Modernism.

Later Life and Legacy

Jonas Lie continued to paint actively throughout his later years, maintaining his focus on landscapes, seascapes, and city views. He remained a respected figure in the American art world until his death in New York City on January 18, 1940, at the age of 59.

His legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he successfully bridged his Norwegian heritage and his American experience, creating a body of work that reflects both influences. He masterfully adapted European Impressionist techniques to capture the unique light and atmosphere of American locales, from the bustling streets of New York to the rugged coast of New England. He was a brilliant colorist and a dynamic composer, capable of conveying both the beauty and the power of his subjects.

Lie's work serves as an important chronicle of America during a period of significant transformation – capturing the rise of the modern city, the grandeur of industrial achievement, and the enduring appeal of the natural landscape. His Panama Canal series remains a unique artistic testament to one of the great engineering feats of the era.

Today, Jonas Lie's paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, and the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, among others. While perhaps overshadowed for a time by later movements like Abstract Expressionism, his work has received renewed appreciation for its technical skill, its vibrant aesthetic, and its insightful portrayal of early 20th-century America. He remains a key figure in the story of American Impressionism and Realism, a painter whose transatlantic vision enriched the nation's artistic heritage. His ability to find beauty in both nature and industry, rendered with characteristic luminosity and vigor, ensures his enduring appeal.