László Mednyánszky stands as one of the most enigmatic and compelling figures in Hungarian art history. Born Baron László Mednyánszky de Medne et Medgyes in 1852 and passing away in 1919, his life spanned a period of immense social, political, and artistic change in Europe. Primarily celebrated as a painter, Mednyánszky was also a keen philosophical thinker, a combination that deeply infused his artistic output. His work, often characterized by atmospheric landscapes and poignant depictions of the marginalized, bridges late 19th-century realism and symbolism with early 20th-century expressive tendencies, securing him a unique place not only within Hungarian art but also in the broader European context. His extensive travels, aristocratic background contrasted with his empathy for the common man, and his experiences as a war artist during World War I all contribute to the rich tapestry of his life and art.

Aristocratic Roots and Early Artistic Formation

László Mednyánszky was born in Beckó, in the Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Beckov, Slovakia), into a landowning aristocratic family. His father, Baron Eduard Mednyánszky, and his mother, Mária Anna Szirmay, both hailed from established noble lineages. This privileged background afforded him opportunities for education and travel unavailable to many. His artistic inclinations manifested early, and in 1863, his family arranged for him to receive guidance from the Austrian painter Thomas Ender, known for his landscape watercolours. This early exposure likely nurtured his innate sensitivity to nature.

Despite his family's expectations, possibly leaning towards estate management or a traditional aristocratic career, Mednyánszky's passion for art prevailed. He pursued formal art education abroad, initially enrolling at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich around 1872-1873. Munich was a significant art centre, though perhaps more conservative than Paris at the time. He later moved to Paris, the epicentre of artistic innovation, studying at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts from 1874 under Professor Isidore Pils. Pils, known for his historical and military scenes, might seem an unlikely mentor for the future landscape and figure painter, but the academic training provided a solid foundation in drawing and composition.

During his time in Paris, Mednyánszky inevitably encountered the burgeoning Impressionist movement, although he never fully adopted its core tenets. More influential, perhaps, were the artists of the Barbizon School, such as Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot. Their focus on realistic depictions of rural life and landscape, often imbued with a sense of mood and atmosphere, resonated with Mednyánszky's developing sensibilities. He spent time painting outdoors in the Fontainebleau forest, absorbing their approach to capturing nature directly, yet already filtering it through his own melancholic temperament.

A Life of Wandering: Travels and Themes

Mednyánszky was, by nature, a wanderer. Despite his noble title and family estates, he spent much of his adult life traveling extensively throughout Europe. His journeys took him across the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including the landscapes of his birth region in Upper Hungary (Slovakia), the vast Hungarian Plain (Alföld), particularly around the artists' colony at Szolnok, and the Carpathian Mountains. He also frequented Paris, Vienna, and visited Italy and potentially other regions. This peripatetic lifestyle was not merely tourism; it was integral to his artistic practice and philosophical outlook.

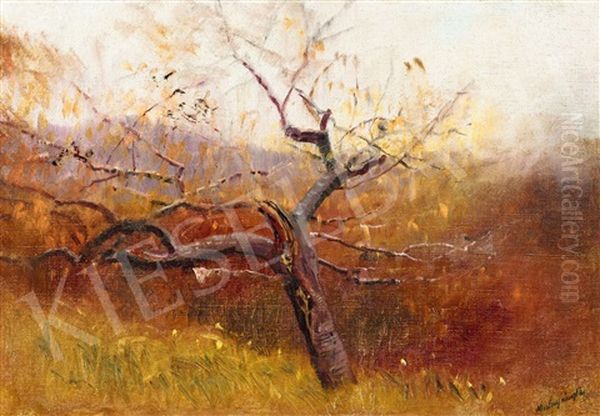

His travels fueled his primary artistic themes. Mednyánszky developed a profound connection with nature, particularly landscapes that seemed wild, untouched, or possessed a certain melancholic grandeur. Misty forests, desolate riverbanks, snow-covered plains, and rugged mountain scenes became recurring motifs. He was less interested in picturesque beauty than in capturing the underlying mood, the atmosphere, and the almost spiritual presence he perceived in the natural world. His landscapes often feel deeply personal, reflecting his own introspective and sometimes somber state of mind.

Equally important was his fascination with humanity, especially those living on the fringes of society. Unlike many artists of his background, Mednyánszky sought out the company of peasants, fishermen, vagrants, soldiers, and the rural poor. He didn't just observe them from a distance; he often lived among them, sharing their conditions. This empathy translated into numerous figure studies and portraits that convey a deep sense of dignity and shared humanity, devoid of sentimentality but rich in psychological insight. His depictions of weathered faces, bent figures, and solitary individuals resonate with a profound understanding of hardship and resilience, echoing the social realism of artists like Gustave Courbet or Honoré Daumier, but filtered through Mednyánszky's unique, often more mystical, lens.

The Evolution of a Unique Style

Mednyánszky's artistic style evolved significantly throughout his career, absorbing various influences while forging a highly personal path. His early works show the impact of his academic training and the Barbizon School's influence, characterized by relatively darker palettes and a focus on tonal values. However, his exposure to Impressionism, likely during his time in Paris, led to a lightening of his palette and a greater interest in capturing the effects of light, though he rarely dissolved form in the manner of Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

By the 1880s, Mednyánszky's work began to show stronger Symbolist tendencies. This wasn't necessarily Symbolism in the vein of Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon, with overt mythological or allegorical content. Instead, Mednyánszky's Symbolism was more atmospheric and psychological. He used landscape and figure not just to represent reality, but to evoke mood, emotion, and philosophical ideas about life, death, and the human condition. His use of colour became more expressive, sometimes employing non-naturalistic hues to enhance the emotional impact. Light and shadow were manipulated for dramatic or mystical effect, often creating a sense of unease or transcendence.

His technique was often experimental and varied. He could employ fine, detailed brushwork, but frequently used broader, more gestural strokes, sometimes applying paint thickly (impasto) to create texture and energy. He was particularly adept at capturing atmospheric effects – mist, fog, twilight, the diffused light of a winter sky – which contributed significantly to the melancholic and mysterious quality of his work. This focus on atmosphere links him to painters like J.M.W. Turner, though Mednyánszky's scale was generally more intimate and his mood more introspective. His style remained distinct from mainstream movements, blending elements of Realism, Impressionism, and Symbolism into a unique synthesis that prioritized emotional truth and philosophical depth.

The Landscape as Soulscape

For Mednyánszky, landscape painting was far more than mere topographical representation; it was a vehicle for exploring the depths of the human spirit and the mysteries of existence. His landscapes often function as "soulscapes," external manifestations of internal states of being. The desolate plains, tangled forests, and brooding mountains he depicted seem to mirror his own complex inner world, marked by introspection, melancholy, and a search for meaning. He was drawn to transitional moments – dawn, dusk, the changing seasons – times when the veil between the physical and spiritual world seems thinnest.

His approach to nature has often been described as pantheistic or mystical. He seemed to perceive a life force or spiritual essence within the natural world, connecting the human soul to the larger cosmos. This is evident in the way he imbued his landscapes with palpable moods – solitude, peace, turmoil, or awe. Trees, rivers, and mountains are not just scenic elements; they often appear as sentient presences, witnesses to the passage of time and the cycles of life and death. This perspective aligns him with the Northern Romantic tradition, particularly artists like Caspar David Friedrich, who also used landscape to convey profound spiritual and emotional experiences.

Mednyánszky's connection to specific regions, like the Carpathian Mountains or the area around his family estate in Strážky (near Beckov), was profound. He returned to these places repeatedly, exploring their changing moods and atmospheres throughout the seasons. His winter landscapes are particularly powerful, capturing the stark beauty and silence of the snow-covered world, often using subtle variations of white, grey, and blue to create scenes of haunting stillness. These works demonstrate his mastery of light and atmosphere, transforming simple natural scenes into meditations on solitude, endurance, and the sublime power of nature.

Portraits of Humanity: Empathy and Insight

Parallel to his landscape painting, Mednyánszky dedicated a significant portion of his oeuvre to depicting human figures, particularly the poor and marginalized. His aristocratic background makes this focus all the more remarkable. He seemed driven by a genuine empathy and a desire to understand the lives of those less fortunate. His figure studies and portraits are characterized by their psychological depth and lack of condescension. He portrayed his subjects – often elderly peasants, weary labourers, vagrants, or soldiers – with a profound sense of dignity and respect.

Unlike formal society portraiture, Mednyánszky's goal was not flattery or the depiction of social status. Instead, he sought to capture the essence of the individual, the marks left by life experience on their faces and bodies. His portraits often convey a sense of quiet suffering, resilience, or contemplation. He used expressive brushwork and a keen observation of posture and facial expression to reveal the inner lives of his subjects. There is a raw honesty in these depictions that recalls the work of Vincent van Gogh in his paintings of peasants, though Mednyánszky's style is generally less agitated and more melancholic.

His interest extended beyond mere observation. His diaries reveal his philosophical reflections on the people he encountered, seeing in their struggles universal truths about the human condition. He often painted solitary figures within landscapes, emphasizing their connection to the natural world or their isolation within it. These works blur the line between portraiture and genre painting, becoming poignant commentaries on existence, poverty, and the passage of time. His ability to convey deep emotion and psychological complexity through relatively simple means is a testament to his skill as both an artist and an observer of humanity.

The Crucible of War: Art from the Front Lines

The outbreak of World War I marked a significant and harrowing chapter in Mednyánszky's life and art. Despite being in his sixties, he volunteered as an official war correspondent and artist attached to the Austro-Hungarian army press corps. He spent considerable time on various fronts, including Galicia, Serbia, and Tyrol, directly witnessing the brutal realities of modern warfare. This experience profoundly impacted him, both personally and artistically, leading to a powerful body of work that stands as a stark testament to the conflict.

His war paintings and sketches moved away from the often-misty lyricism of his earlier landscapes towards a more direct, sometimes brutally realistic, depiction of suffering and death. He captured scenes of exhausted soldiers marching, wounded men in field hospitals, desolate battlefields littered with debris, and the haunting presence of death. His palette sometimes became darker and more somber, or employed stark contrasts of light and shadow to heighten the drama and tragedy of the scenes. Works from this period convey an overwhelming sense of loss, futility, and compassion for the common soldier caught in the maelstrom.

One of his most notable works from this era is often titled Menekülők (variously translated as Refugees, Fugitives, or sometimes referencing specific military actions). These paintings typically depict columns of weary soldiers or civilians, trudging through bleak landscapes, their faces etched with exhaustion and despair. They are powerful indictments of the human cost of war, focusing not on heroism or glory, but on the shared suffering and endurance of ordinary people. Mednyánszky's war art is considered among the most significant artistic responses to World War I produced within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, valued for its emotional honesty and profound humanism. The physical and psychological toll of his war experiences, possibly exacerbated by lead poisoning from his paints, likely contributed to his declining health in the final years of his life.

Philosophical Underpinnings and Personal Beliefs

László Mednyánszky was not just a painter; he was a deeply reflective individual, and his art cannot be fully understood without considering his philosophical inclinations. He kept extensive diaries throughout his life, filled with personal reflections, observations, and philosophical musings. These writings reveal a complex mind grappling with questions of existence, suffering, spirituality, and the nature of reality. He was drawn to various philosophical and spiritual traditions, notably the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and aspects of Eastern thought, particularly Buddhism.

Schopenhauer's emphasis on the inherent suffering in existence and the possibility of transcending the relentless will through aesthetic contemplation likely resonated with Mednyánszky's own temperament and his observations of hardship. His empathy for the poor and suffering can be seen as reflecting a Schopenhauerian or Buddhist understanding of universal suffering (Dukkha). His landscapes, particularly those emphasizing solitude and the vastness of nature, might be interpreted as attempts to find solace or achieve a state of detached contemplation, momentarily escaping the struggles of the individual ego.

His interest in Buddhism and mysticism also informed his worldview. He seemed to believe in a form of pantheism or panentheism, seeing a spiritual connection between all living things and the cosmos. This is reflected in the atmospheric unity of his landscapes and his sensitive portrayal of both humans and animals. His diaries also contain passages suggesting mystical experiences or a belief in supernatural connections, including references to communicating with deceased friends. While some of his more esoteric ideas were perhaps unconventional, they underscore the depth of his spiritual searching and his desire to imbue his art with meanings beyond the purely visual. This philosophical depth adds another layer to his work, distinguishing him from artists focused solely on formal or aesthetic concerns.

Representative Works in Focus

Several key works exemplify Mednyánszky's style and thematic concerns:

Menekülők (Refugees/Fugitives, c. 1915-1916): As mentioned, this title often refers to a series of works depicting the grim reality of war. Typically showing columns of soldiers or displaced people moving through desolate, often wintry landscapes, these paintings convey profound exhaustion, suffering, and the dehumanizing effects of conflict. The brushwork is often loose and expressive, the colours somber, emphasizing the bleak atmosphere and the collective anonymity of the sufferers.

Táborozás (Encampment) or Trén (Supply Train, c. 1914-1918): Another theme related to his war experience or observations of military life. These works often depict soldiers at rest, supply wagons, or camp scenes, usually set within a landscape. While less overtly tragic than the Menekülők series, they still convey a sense of weariness and the mundane hardships of military life, often rendered with his characteristic atmospheric sensitivity.

Elítélt (The Condemned/The Convict, c. 1880s-1890s): This title is associated with several works, often depicting a solitary, brooding male figure, sometimes in peasant or vagrant attire, set against a stark landscape or simple interior. The figure's posture and expression convey a sense of inner turmoil, resignation, or alienation. These works are powerful psychological studies, exploring themes of fate, judgment, and existential solitude, reflecting Mednyánszky's interest in the darker aspects of the human condition. (Note: Some sources mention a cat in relation to this title, but the dominant imagery associated with Elítélt is typically the human figure).

Decaying Street Scene (Various titles, e.g., Utcarészlet - Street Detail): Mednyánszky painted numerous urban scenes, often focusing on dilapidated buildings, quiet backstreets, or melancholic cityscapes, particularly in Paris or Hungarian towns. These works capture a sense of time passing, neglect, and the quiet poetry of decay, often using subtle light effects and muted colours to create a poignant atmosphere.

Norwegian Fjord (or similar titles from travels): While most famous for his Central European landscapes, Mednyánszky did travel. Works depicting scenes like Norwegian fjords showcase his ability to adapt his style to different environments, capturing the unique light and grandeur of northern landscapes while maintaining his characteristic focus on mood and atmosphere.

These examples highlight the range of Mednyánszky's subjects – from the epic scale of war to intimate psychological portraits and evocative landscapes – all unified by his distinctive artistic vision and philosophical depth.

Contemporaries, Context, and Influence

László Mednyánszky operated within a rich and dynamic European art scene. His career overlapped with major movements, and while he remained largely independent, his work shows awareness of and dialogue with contemporary trends. His early development was shaped by the lingering influence of Realism (Gustave Courbet) and the Barbizon School (Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, Camille Corot). His time in Paris exposed him to Impressionism (Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro), whose emphasis on light and plein air painting affected his technique, though he prioritized mood over optical effects.

His affinity for Symbolism connects him to artists exploring subjective experience and inner worlds, such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon in France, or Edvard Munch in Scandinavia, whose emotional intensity finds echoes in Mednyánszky's more charged works. Within the Austro-Hungarian context, he was a contemporary of prominent Hungarian painters like Mihály Munkácsy, whose dramatic Realism differed significantly in style and subject, and Pál Szinyei Merse, a key figure in Hungarian Impressionism. He also worked alongside artists associated with the Nagybánya artists' colony (e.g., Károly Ferenczy) and knew figures like József Rippl-Rónai, who brought Post-Impressionist and Nabis influences back to Hungary.

Mednyánszky's influence on subsequent generations of Hungarian artists is significant, though perhaps subtle. His deep connection to the Hungarian landscape and his empathetic portrayal of its people provided a touchstone for artists seeking authentic national expression. His willingness to blend realism with subjective emotion paved the way for more expressive styles in the 20th century. Artists like Vilmos Aba-Novák, who reportedly worked with Mednyánszky during the war years, show traces of his influence in their dynamic compositions and social themes, albeit often with a more robust and less melancholic sensibility. Mednyánszky's unique position, bridging 19th-century traditions with modern psychological depth, ensured his enduring relevance.

Reception, Legacy, and Personal Life

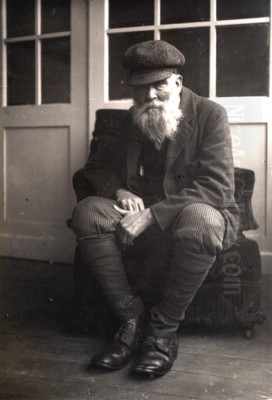

During his lifetime, Mednyánszky achieved considerable recognition, exhibiting regularly in Budapest, Vienna, and Paris. However, his unconventional lifestyle and deeply personal, often somber, art also provoked mixed reactions. Some critics lauded his originality and emotional depth, while others found his style too eccentric or his subject matter depressing. One contemporary critique mentioned his work imposing a "physical and moral burden," suggesting its challenging nature for conventional tastes. Despite this, his reputation as a major figure in Hungarian art was solidified by the early 20th century.

His legacy is preserved primarily through his vast body of work, estimated at several thousand paintings and drawings. Major collections are held at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest and the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava, which houses many works related to his origins and time spent in Strážky. His art continues to be studied and appreciated for its technical skill, atmospheric power, and profound humanism. His diaries, published posthumously, offer invaluable insights into his thoughts, working methods, and personal life, revealing a complex personality – aristocratic by birth, yet drawn to simplicity and solitude; deeply intellectual, yet highly intuitive and emotional.

Aspects of his personal life, including his apparent lifelong bachelorhood and intense emotional connections with certain male friends (as documented in his diaries), have led scholars to discuss his probable homosexuality. In the context of his time, this would have been a private matter, but it adds another layer to understanding his sense of alienation, his empathy for outsiders, and the coded emotional intensity in some of his works. His final years were marked by ill health, exacerbated by his war experiences and possibly lead poisoning. He died in Vienna in 1919, leaving behind a legacy as one of Central Europe's most distinctive and moving painters.

Conclusion: Painter of Mood and Spirit

László Mednyánszky remains a towering figure in Hungarian art, a painter whose work transcends easy categorization. He was a master landscapist who captured not just the appearance of nature, but its soul. He was a sensitive portraitist who depicted the dignity and hardship of the common person with profound empathy. He was a war artist who chronicled the suffering of conflict with unflinching honesty. And he was a philosopher whose spiritual and existential searching infused every brushstroke.

His unique style, blending elements of Realism, Impressionism, and Symbolism, created a visual language perfectly suited to his themes of nature, humanity, and the passage of time. He navigated the complex artistic currents of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, absorbing influences yet always maintaining his distinct voice. From the misty forests of the Carpathians to the battlefields of World War I, from the weathered faces of vagrants to the solitude of his own soul, Mednyánszky's art offers a deep, melancholic, and ultimately compassionate vision of the world. His enduring power lies in his ability to connect the external landscape with the internal human condition, making him a timeless painter of mood, atmosphere, and spirit.