August Macke stands as one of the most radiant figures in German Expressionism, a painter whose tragically short life belied the sheer volume and vibrancy of his artistic output. A key member of the influential Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group, Macke developed a unique style characterized by luminous colour, a fascination with modern life, and an optimistic sensibility that set him apart from some of his more angst-ridden contemporaries. Though his career spanned less than a decade, cut short by the outbreak of World War I, his work continues to resonate, offering a window onto a world perceived through prisms of light and pure, joyous pigment. This exploration delves into the life, art, and legacy of this remarkable German artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

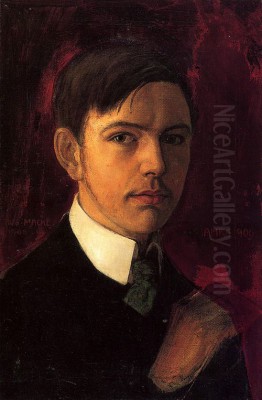

August Robert Ludwig Macke was born on January 3, 1887, in Meschede, Westphalia, Germany. His father, August Friedrich Hermann Macke, was a building contractor and civil engineer, while his mother, Maria Florentine Macke (née Adolph), came from a farming family. The family moved to Cologne when August was very young, and later to Bonn in 1900. It was in Bonn that Macke's artistic inclinations began to truly flourish, nurtured perhaps by the artistic interests of his father and an uncle. He attended the Realgymnasium in Bonn, where his encounters with fellow student Hans Thuar marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

His formal artistic training began in 1904 when he enrolled at the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts). However, Macke found the academic curriculum stifling and conventional. He sought more progressive instruction, attending evening classes at the Düsseldorf School of Applied Arts alongside his academy studies. During this period, he also designed stage sets and costumes for the Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, working under Louise Dumont and Gustav Lindemann, an experience that likely honed his sense of colour and composition.

Macke left the Academy in 1906, feeling he had gained little from its rigid methods. His artistic direction was already being shaped by other forces. He had encountered Impressionism, and its focus on light and contemporary subject matter struck a chord. A pivotal moment came with his first trip to Paris in 1907.

Parisian Revelations and the Embrace of Colour

Paris was a crucible of artistic innovation, and Macke absorbed its energy voraciously. He encountered the works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists firsthand. While the Impressionists' handling of light was influential, it was the bold, arbitrary use of colour by the Fauves, particularly Henri Matisse, that had a profound impact. He also deeply admired the structural compositions of Paul Cézanne, whose work provided a counterpoint to the purely decorative tendencies he sometimes perceived in Fauvism.

Further travels broadened his horizons. He visited Italy with his future wife, Elisabeth Gerhardt, and spent time in Berlin studying under Lovis Corinth at his private art school. Corinth, a leading figure bridging Impressionism and Expressionism in Germany, offered a different perspective, though Macke ultimately forged his own path. A subsequent, longer stay in Paris in 1908 solidified his engagement with the French avant-garde. He became particularly interested in the way artists like Matisse used colour not just descriptively, but emotionally and structurally.

These early experiences laid the groundwork for Macke's signature style. He began to move away from the darker palettes sometimes associated with German art, embracing brighter hues and exploring the interplay of colour harmonies and contrasts. His subject matter increasingly focused on the world around him – people in parks, strolling along streets, gazing into shop windows – rendered with a growing confidence and chromatic brilliance.

The Crucial Friendship: Franz Marc

A defining relationship in Macke's life and artistic development began in January 1910. While visiting Munich, the burgeoning centre of German avant-garde art, Macke met Franz Marc. The connection was immediate and profound. Marc, slightly older and already exploring symbolic uses of colour and animal forms, found in Macke a kindred spirit – enthusiastic, open to new ideas, and possessing an innate gift for colour.

Their friendship blossomed through correspondence and visits. They shared ideas, critiqued each other's work, and spurred each other towards greater artistic innovation. Marc was deeply impressed by Macke's intuitive handling of colour and his ability to capture the vibrancy of life. Macke, in turn, benefited from Marc's more theoretical inclinations and his connections within the Munich art scene. They shared a deep love for nature and a desire to express spiritual and emotional truths through art, though their approaches differed – Marc often sought the monumental and symbolic, while Macke found profundity in the everyday.

This friendship became a cornerstone of the nascent Expressionist movement in Munich. Together, they represented a lyrical, colour-focused wing of Expressionism, distinct from the more psychologically intense work being produced by Die Brücke (The Bridge) artists in Dresden and Berlin. Their shared journey would soon lead to the formation of one of the most important artist groups of the early 20th century.

Forging Der Blaue Reiter

The Munich art world at the time was dominated by established institutions that were often resistant to new artistic trends. Franz Marc was involved with the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM – New Artists' Association of Munich), a group that included Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, Gabriele Münter, and Marianne von Werefkin. However, tensions arose within the NKVM over the direction of modern art, particularly regarding abstraction.

In 1911, when Kandinsky's abstract painting Composition V was rejected by the NKVM jury for an upcoming exhibition, Kandinsky, Marc, Münter, and Macke decided to break away and form their own group. They quickly organized a counter-exhibition, titled the "First Exhibition of the Editors of Der Blaue Reiter," which opened in December 1911 at the Thannhauser Gallery in Munich, running concurrently with the NKVM show it had seceded from.

The name "Der Blaue Reiter" (The Blue Rider) was chosen, according to Kandinsky, because both he and Marc loved blue, Marc liked horses, and Kandinsky liked riders. It symbolized their forward momentum and their spiritual aspirations in art. Macke was a crucial participant from the outset, contributing several works to the first exhibition. Though perhaps less theoretically inclined than Kandinsky or Marc, his vibrant paintings perfectly embodied the group's emphasis on inner expression, spiritual resonance, and the autonomous power of colour and form.

The Blue Rider was not a movement with a strict manifesto like Die Brücke, but rather a loose association of artists united by a common goal: to showcase the diversity of authentic artistic expression that they felt was being ignored by the establishment. Their exhibitions included works by international artists like Robert Delaunay from France and Arnold Schoenberg (the composer, who also painted) from Austria, reflecting their cosmopolitan outlook. They also published the influential Blue Rider Almanac in 1912, edited by Kandinsky and Marc, which featured essays and reproductions advocating for a synthesis of the arts and exploring connections between modern art, folk art, children's art, and non-European art forms. Macke contributed an essay titled "Masks" to the Almanac.

Macke's Distinctive Style: Colour as Emotion

Within the context of Der Blaue Reiter and German Expressionism, Macke carved out a unique artistic identity. While sharing the Expressionist emphasis on subjective experience over objective reality, his work generally lacked the anxiety and social critique found in the art of Die Brücke members like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Instead, Macke's paintings radiate a sense of harmony, optimism, and delight in the visual world.

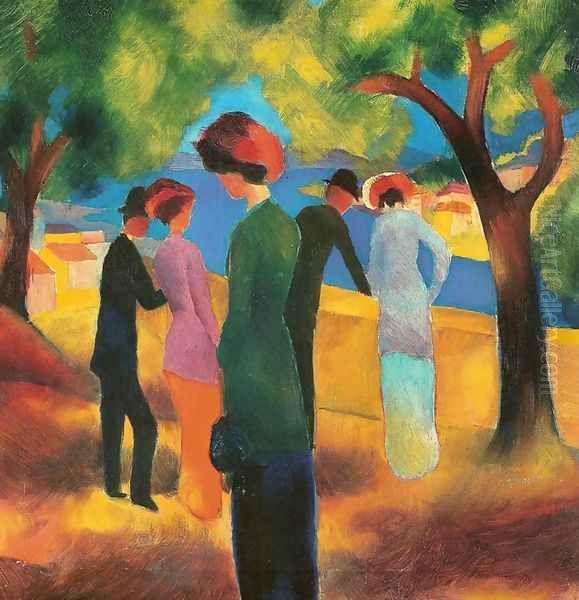

His use of colour became increasingly sophisticated. Influenced by the Orphism, or Simultaneism, of the French painter Robert Delaunay, whom he met in Paris in 1912, Macke began experimenting with structuring his compositions through interlocking planes of pure, luminous colour. Delaunay's theories about the simultaneous contrast of colours and their ability to create rhythm and depth resonated deeply with Macke's own sensibilities. This is evident in works like Zoological Garden I (1912) or Promenade (1913), where figures and settings dissolve into vibrant patchworks of light and colour, creating a sense of dynamic movement and sensory pleasure.

Macke's favourite subjects were scenes of modern leisure and urban life: women admiring hats in shop windows (Hat Shop, 1914), elegantly dressed figures strolling in parks or botanical gardens, children playing, cafes, and sunlit streets. He had a particular fondness for depicting women, often his wife Elisabeth, in fashionable attire, capturing the fleeting moments of everyday existence with grace and charm. Works like Lady in a Green Jacket (1913) or Woman with an Umbrella in Front of a Hat Shop (1914) showcase his ability to combine elegant figuration with bold chromatic harmonies.

His compositions often employed simplified forms and flattened perspectives, emphasizing the surface pattern and the interaction of colours. He masterfully captured the effects of light, not through traditional chiaroscuro, but through the juxtaposition of warm and cool colours, creating a sense of shimmering atmosphere. There is a gentle, lyrical quality to his work, a celebration of life's simple beauties rendered in a language of pure, unadulterated colour.

Connections and Influences: Beyond the Blue Rider

While Der Blaue Reiter was his primary artistic family, Macke maintained connections and absorbed influences from various quarters. He exhibited alongside Die Brücke artists in major shows like the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne in 1912, which provided a comprehensive overview of European modern art. Although his style differed significantly from the rawer, more angular forms of Kirchner or Erich Heckel, he shared their commitment to breaking from academic tradition and forging a new, expressive German art. He particularly admired Emil Nolde, another artist loosely associated with Die Brücke, known for his intense colourism.

His friendship with Hans Thuar remained important. Living near Bonn again from late 1913, Macke became a central figure among the Rhenish Expressionists. He helped organize the "Exhibition of Rhenish Expressionists" in Bonn in 1913, ensuring his friend Thuar was included. This period saw him consolidating his mature style, producing some of his most iconic works.

The influence of French art, particularly Delaunay, remained crucial. Macke's engagement with Orphism provided him with tools to structure his compositions chromatically, moving beyond Fauvist spontaneity towards a more deliberate, yet still vibrant, organization of the picture plane. He synthesized these French influences with his German Expressionist roots and his own innate sensitivity to create a style entirely his own.

The Tunisian Journey: A Final Burst of Light

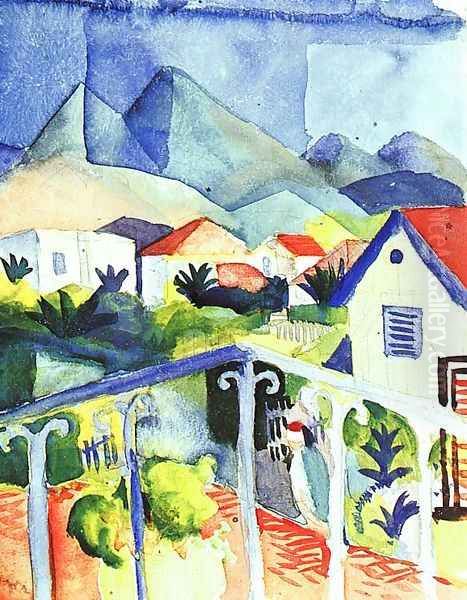

In April 1914, Macke embarked on a journey that would prove to be a culminating experience of his artistic life. Together with his fellow artists Paul Klee and Louis Moilliet, he traveled to Tunisia in North Africa. Klee, who had known Macke since 1911, and Moilliet, a Swiss painter also connected to the Blue Rider circle, shared Macke's fascination with light and colour.

The intense light, exotic architecture, vibrant colours, and unfamiliar culture of Tunisia had an electrifying effect on Macke. Working primarily in watercolour, a medium perfectly suited to capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, he produced a series of works that are considered among the high points of his career and masterpieces of early 20th-century watercolour painting.

In works like View into a Lane, St. Germain near Tunis, or Kairouan III, Macke translated the North African environment into dazzling compositions of translucent colour planes. The light seems to emanate from within the colours themselves. Forms are simplified, almost abstracted, yet retain a connection to the observed world. The Tunisian watercolours represent a perfect synthesis of observation, emotion, and chromatic structure, imbued with a sense of serene harmony and wonder. Klee famously declared during this trip, "Colour possesses me... Colour and I are one. I am a painter." Macke, already a master colourist, reached new heights of luminosity and expressive freedom.

He returned to Germany in June 1914, energized and full of new artistic ideas inspired by the trip. He immediately began translating his watercolour studies into oil paintings, poised for a new phase of creative development. But the world was on the brink of catastrophe.

War and Tragic End

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 shattered the vibrant artistic world Macke inhabited. Like many artists of his generation, including his close friend Franz Marc, Macke was caught up in the initial wave of patriotic fervor and enlisted in the German army. He was sent to the Western Front as part of the infantry.

His letters home reveal a growing disillusionment with the realities of war, but also moments where his artist's eye still found beauty amidst the destruction. His promising career and life were brutally cut short. On September 26, 1914, during fighting near Perthes-lès-Hurlus in the Champagne region of France, August Macke was killed in action. He was only 27 years old.

His death was a devastating blow to the German avant-garde and the broader world of modern art. Franz Marc, who would himself be killed at Verdun less than two years later, mourned his friend deeply, writing that Macke had given colour "the clearest and purest sound of all of us." The loss of these two central figures, along with the scattering of other artists due to the war (Kandinsky returned to Russia, Jawlensky and Werefkin went to Switzerland), effectively marked the end of the Der Blaue Reiter group.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the brevity of his career – essentially spanning from 1907 to 1914 – August Macke left behind a significant body of work, including hundreds of paintings, thousands of drawings, and the remarkable Tunisian watercolours. His legacy is preserved thanks in large part to the efforts of his wife, Elisabeth Gerhardt Macke, who carefully managed his estate and ensured his works found homes in major public collections. The Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich, famous for its extensive Blue Rider collection, holds many important works by Macke, as do museums in Bonn, Münster, and elsewhere in Germany and internationally.

Macke's influence lies in his unique synthesis of German Expressionist intensity with French chromatic elegance. He demonstrated that Expressionism did not have to be solely about angst and turmoil; it could also celebrate the beauty and vibrancy of the modern world. His mastery of colour, his ability to capture light, and his focus on everyday life provided a lyrical counterpoint within the broader Expressionist movement.

He stands as a bridge figure, connecting Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Orphism, and Expressionism. While his direct influence on subsequent movements like Abstract Expressionism is debatable, his emphasis on the autonomous power of colour and the expression of inner feeling through non-naturalistic means certainly contributed to the broader trajectory of modern art towards abstraction.

Today, August Macke is remembered as a painter of light and life. His works continue to captivate viewers with their radiant colours, harmonious compositions, and gentle, optimistic spirit. He captured a fleeting moment in European culture – the vibrant, hopeful, yet ultimately fragile world of the Belle Époque just before it was consumed by war. His art remains a poignant testament to a brilliant talent extinguished far too soon, a luminous vision that continues to shine.