Introduction: The Third Musketeer of Cubism

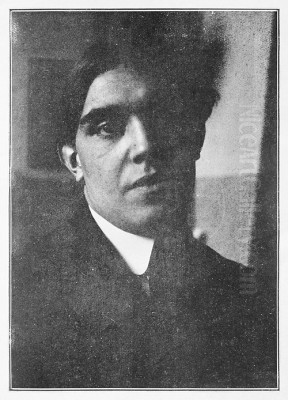

In the revolutionary landscape of early 20th-century art, Cubism stands as a monumental shift, shattering traditional perspectives and reshaping the very definition of painting. While the names Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque are inextricably linked to its genesis, a third figure, Juan Gris, completed this foundational triumvirate. Born José Victoriano Carmelo Carlos González-Pérez in Madrid on March 23, 1887, Gris brought a unique intellectual rigor, a vibrant chromatic sensibility, and a profound sense of order to the Cubist movement. Though his life was tragically cut short on May 11, 1927, in Boulogne-sur-Seine, France, due to kidney failure (uremia), his contributions were pivotal, bridging the initial analytical phase of Cubism with its more structured synthetic evolution, and leaving an indelible mark on modern art. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of Juan Gris, the Spanish master who found his artistic voice in the heart of Parisian modernism.

From Madrid Engineering Student to Parisian Illustrator

Juan Gris's journey into the art world was not a direct path. Born into a well-to-do family in Madrid, he initially pursued a more conventional route, studying mechanical drawing at the Escuela de Artes y Manufacturas from 1902 to 1904. During this period, however, his artistic inclinations began to surface more strongly. He started contributing drawings and humorous cartoons, often satirical in nature, to various local periodicals, including Blanco y Negro and Madrid Cómico. This early work, though distinct from his later painterly style, honed his drafting skills and perhaps hinted at the sharp wit and observational acuity that would later inform his art.

Around 1904-1905, Gris began to focus more seriously on painting, studying under the academic artist José Maria Carbonero. However, the traditional artistic environment of Madrid ultimately proved insufficient for his burgeoning modernist sensibilities. Like many ambitious young artists of his generation, Gris felt the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed capital of the avant-garde. In 1906, at the age of 19, seeking to avoid military service and immerse himself in the vibrant artistic milieu, he made the decisive move to France. This relocation marked the most significant turning point in his early life, setting the stage for his transformation into a major figure of modern art.

Arrival in Paris: The Bateau-Lavoir Crucible

Upon arriving in Paris, Gris settled in the legendary Bateau-Lavoir building in Montmartre, a dilapidated complex of artists' studios that served as a nerve center for the burgeoning avant-garde. Fatefully, his neighbor was none other than his compatriot, Pablo Picasso. This proximity proved crucial. Gris quickly integrated into the circle of artists and writers surrounding Picasso, which included figures like Georges Braque, the poet Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire (who would become a key critical supporter of Cubism), André Salmon, and others who were actively forging new artistic paths.

Initially, Gris continued to support himself by producing illustrations and satirical drawings for publications such as the anarchist journal L'Assiette au Beurre and Le Charivari. This work provided necessary income but also kept him connected to visual expression while he absorbed the radical artistic experiments happening around him. He witnessed firsthand the development of early Cubism by Picasso and Braque between 1907 and 1910. He observed their deconstruction of form, their analysis of objects from multiple viewpoints, and their increasingly monochromatic palettes. Gris was a keen observer and a thoughtful intellect, and he spent several years assimilating these revolutionary ideas before fully committing himself to painting in the Cubist idiom.

Embracing Cubism: Finding His Voice

Around 1910-1911, Juan Gris began to dedicate himself seriously to painting, moving away from illustration. His initial works started to show the clear influence of the Analytical Cubism pioneered by Picasso and Braque. This early phase of Cubism involved dissecting objects and figures into fragmented geometric planes, often rendered in muted tones of ochre, grey, and brown, emphasizing form and structure over color. Gris absorbed these principles, but even in his early Cubist works, a distinct personality began to emerge.

His painting Homage to Picasso (1912) is a landmark work from this period. It demonstrates his mastery of the Analytical Cubist vocabulary – the fractured planes, the overlapping perspectives, the subdued palette – yet it also possesses a clarity and structural logic that hints at his future direction. Unlike the sometimes near-abstract fragmentation in Picasso's and Braque's work of the time, Gris's portrait retains a greater degree of representational legibility, organized within a firm compositional grid. It was a declaration of his arrival as a serious Cubist painter and a respectful nod to the movement's leading figure, who was also his friend and mentor.

The Breakthrough Year: 1912

The year 1912 was pivotal for Juan Gris. He burst onto the public scene, exhibiting for the first time at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris with several works, including the aforementioned Homage to Picasso. This exhibition marked his definitive commitment to the Cubist style and brought his work to wider attention. His paintings stood out for their systematic approach and emerging chromatic richness compared to the more austere works of early Analytical Cubism.

Later that year, Gris participated in another significant group exhibition, the Salon de la Section d'Or, held at the Galerie La Boétie. This exhibition brought together a diverse group of artists associated with Cubism and its offshoots, including Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger (co-authors of the first treatise on Cubism, Du "Cubisme", published that same year), Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Jacques Villon, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon. While Picasso and Braque remained aloof from these larger group shows, the Section d'Or helped to codify and disseminate Cubist ideas, and Gris's participation solidified his position within the broader movement. His work was noted for its distinct clarity and structure.

Perhaps the most crucial development of 1912 was securing a contract with the influential art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Kahnweiler was the primary dealer for Picasso and Braque and a key champion of Cubism. Having Kahnweiler's support provided Gris with financial stability and critical validation, allowing him to focus entirely on his artistic development. This relationship would prove essential throughout much of Gris's career.

Developing a Unique Voice: Synthetic Cubism and Papier Collé

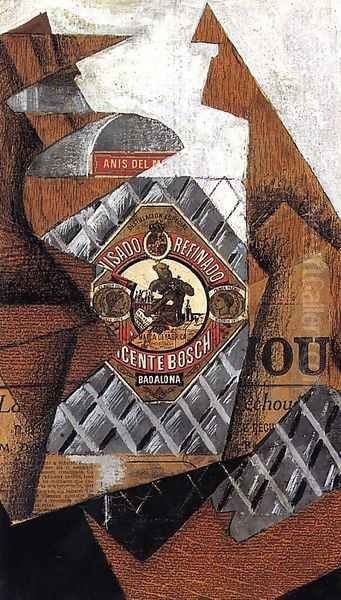

While Gris initially adopted the language of Analytical Cubism, he quickly became a key figure in the development of its next phase: Synthetic Cubism. Emerging around 1912-1913, Synthetic Cubism moved away from the complex fragmentation of the analytical phase towards constructing, or synthesizing, images from simpler, flatter shapes, brighter colors, and, significantly, incorporating real-world materials.

Gris was a pioneer, alongside Picasso and Braque, in the technique of papier collé (pasted paper or collage). However, his approach differed subtly but significantly. While Picasso and Braque often used fragments of newspaper, wallpaper, or other materials to disrupt the pictorial surface, introduce elements of "reality," and play with representation, Gris tended to integrate these elements more seamlessly into his compositions. He used collage not just as a disruptive element but as a constructive one, incorporating pieces of paper as flat planes of color and texture that were integral to the overall design. Works like The Washstand (1912) or Violin and Glass (1913) exemplify his early mastery of this technique, where pasted elements function as both representation and abstract shape within a tightly organized structure.

His method was often described as more deductive or conceptual compared to the more intuitive approach of Picasso and Braque. Gris famously stated, "I try to make concrete that which is abstract. Cézanne turns a bottle into a cylinder, but I begin with a cylinder and create an individual object of a special type: I make a bottle out of a cylinder." This suggests a process that started with an abstract geometric structure or idea, which he then imbued with specific representational details. This intellectual underpinning gave his Synthetic Cubist works a characteristic clarity, balance, and architectural solidity.

Color, Composition, and Intellectual Rigor

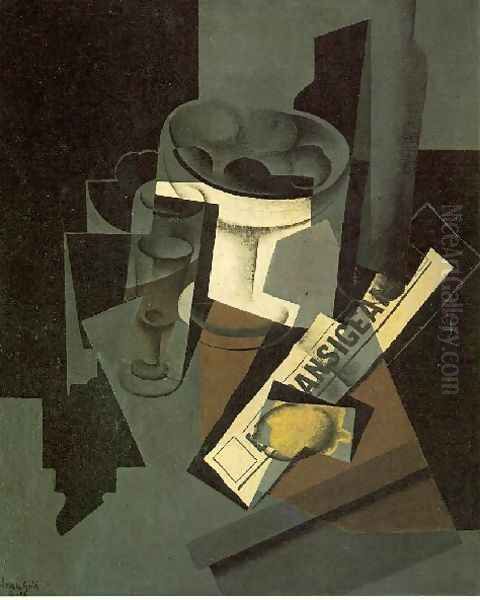

One of the most distinguishing features of Juan Gris's Cubism is his sophisticated and deliberate use of color. While Analytical Cubism had largely restricted itself to a near-monochromatic palette, Gris, particularly as he moved into Synthetic Cubism, reintroduced vibrant and harmonious color combinations. He didn't use color merely for description but as an essential structural element, creating complex interactions between flat, colored planes. His palettes often featured rich blues, greens, browns, and whites, carefully balanced to create both visual appeal and compositional coherence.

His compositions were equally distinctive. Gris possessed an innate sense of order and structure, often organizing his paintings around clear geometric grids, diagonals, and stable forms. Even when depicting fragmented objects from multiple viewpoints, there is an underlying logic and harmony to his arrangements. This structured approach led some critics to see his work as more "classical" or "pure" compared to the more dynamic and sometimes chaotic energy found in the works of Picasso or Braque. His still lifes, a favored genre, became intricate arrangements of objects like guitars, bottles, fruit bowls, newspapers, and glasses, transformed into elegant essays on form, color, and light, all held together by his rigorous compositional intelligence. This systematic quality became even more pronounced in the later phase sometimes referred to as Crystal Cubism.

The War Years and Crystal Cubism

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 significantly impacted the Parisian art world. Many artists were mobilized, and foreigners like Gris faced uncertain circumstances. His dealer, Kahnweiler, being German, had his gallery sequestered and was forced into exile in Switzerland, leaving Gris without his primary financial and critical support for a time. Despite these difficulties, Gris continued to work, spending time in Collioure and later returning to Paris. He also spent time in Céret, a town in the French Pyrenees where Picasso and Braque had worked earlier, sometimes working alongside Picasso and the sculptor Manolo Hugué.

During and immediately after the war years (roughly 1915-1920), Gris's style continued to evolve, moving towards what is often termed "Crystal Cubism." This phase, shared to some extent by other Cubists like Metzinger and Gleizes, represented a consolidation and clarification of Cubist principles. It was characterized by simplified, overlapping geometric planes, a greater emphasis on flat surfaces, precise outlines, and a highly ordered, almost crystalline structure. Color remained important, but the compositions became even more stable and architectonic. Works like Still Life with Checkered Tablecloth (1915) or Fruit Dish, Glass and Lemon (1916) exemplify this move towards greater clarity and purification of form, reflecting perhaps a broader post-war desire for order and reconstruction, often referred to as the "Return to Order" (Rappel à l'ordre) in the arts.

Beyond Painting: Stage Design and Theory

While primarily known as a painter, Juan Gris also extended his artistic talents to other domains, most notably stage and costume design. In the early 1920s, he collaborated with Sergei Diaghilev, the impresario of the famous Ballets Russes. This company was renowned for commissioning cutting-edge artists and composers. Gris designed sets and costumes for several productions, including Les Tentations de la Bergère (The Temptations of the Shepherdess, 1924) with music by Michel Pignolet de Montéclair, and La Colombe (The Dove, 1924).

His designs translated his Cubist aesthetic into three dimensions, using bold geometric shapes, vibrant colors, and flattened perspectives suitable for the stage. This work brought him into collaboration with other major figures associated with the Ballets Russes, such as Henri Matisse, who also designed for the company, and potentially exposed his work to a wider international audience. Other artists who famously worked with Diaghilev included Léon Bakst, Natalia Goncharova, and, of course, Picasso himself, highlighting the cross-pollination between easel painting and theatrical design during this period.

Beyond his practical artistic output, Gris was also an articulate theorist of his own work and of Cubism more broadly. He believed deeply in the intellectual foundations of his art. In 1924, he delivered a significant lecture at the Sorbonne titled "Des possibilités de la peinture" (On the Possibilities of Painting), later published, in which he outlined his artistic philosophy. He emphasized the distinction between analytical and synthetic approaches and articulated his belief in painting as an autonomous art form, a "flat, colored architecture," constructed from abstract elements rather than simply imitating reality. These theoretical contributions further solidified his reputation as one of the most thoughtful and articulate proponents of Cubism.

Later Life, Style, and Themes

Throughout the 1920s, Juan Gris continued to refine his distinctive style. His paintings from this period often feature a remarkable synthesis of clarity, complexity, and chromatic richness. Recurring themes dominate his canvases: the familiar still life objects – guitars (a particularly Spanish motif), violins, fruit bowls, pipes, books, newspapers – often arranged on tabletops. He also frequently employed the motif of the open window, skillfully juxtaposing interior still life elements with glimpses of exterior landscapes or architectural features, creating complex spatial dialogues within the picture plane, as seen in works like The Open Window (1921).

Figures, particularly harlequins and pierrots (figures from the Commedia dell'arte tradition, also favored by Picasso), appear more frequently in his later work, rendered in his characteristic style of flattened, overlapping planes and bold colors, such as in Seated Harlequin (1923). These works possess a certain elegance and decorative quality, yet they retain the underlying structural rigor that defined his entire oeuvre.

Despite his artistic successes, Gris's health was increasingly fragile. He suffered from bouts of pleurisy and was diagnosed with asthma and emphysema, which often forced him to seek healthier climates away from Paris. His personal life also saw changes; after his early marriage to Lucie Belin, with whom he had a son, Georges, he later formed a lasting relationship with Josette Herpin. Tragically, his chronic health problems culminated in severe kidney disease. Despite receiving treatment from prominent doctors, his condition worsened rapidly. Juan Gris died of uremia on May 11, 1927, in Boulogne-sur-Seine, near Paris, at the young age of 40.

Legacy and Influence

Although his career spanned less than two decades, Juan Gris's impact on 20th-century art was profound and lasting. As the "third Cubist," he played an essential role in the movement's development, offering a distinct alternative to the approaches of Picasso and Braque. His emphasis on structure, clarity, and intellectual control provided a crucial counterpoint to their more intuitive and sometimes volatile explorations. His systematic development of Synthetic Cubism and his innovative use of papier collé were highly influential.

Gris's rational, ordered approach to Cubism resonated strongly with subsequent movements that sought clarity and objectivity. The Purist movement, founded by Amédée Ozenfant and the architect Le Corbusier shortly after World War I, which advocated for clean lines, geometric forms, and machine-age aesthetics, certainly owed a debt to Gris's structured compositions. His emphasis on the painting as an autonomous construction, a "flat, colored architecture," anticipated later developments in abstract art.

Gertrude Stein, the influential American writer and collector residing in Paris, was a great admirer and supporter of Gris, famously writing about him and considering him a painter of profound integrity. His work was collected by other key patrons of modern art and entered major museum collections worldwide. Artists like the Cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz were close friends and colleagues. While perhaps not achieving the same level of household fame as Picasso, Gris remains a pivotal figure for understanding the full scope and potential of Cubism. His unique synthesis of intellectual rigor and aesthetic sensibility, his mastery of color and composition, and his unwavering commitment to his artistic vision secure his place as one of the indispensable masters of modern art.

Conclusion: The Architect of Cubist Synthesis

Juan Gris stands as a testament to the power of intellectual clarity combined with artistic sensitivity. Arriving in Paris as a young illustrator, he absorbed the revolutionary atmosphere of early modernism and quickly forged a unique and indispensable path within Cubism. He brought order to fragmentation, vibrant color to analytical austerity, and theoretical depth to painterly practice. Through his mastery of Synthetic Cubism, his pioneering use of collage, his elegant compositions, and his articulate defense of his artistic principles, Gris demonstrated that Cubism could be a language of harmony and structure as much as one of disruption. His tragically short life ended a career that was still evolving, yet the body of work he left behind remains a cornerstone of 20th-century art – a legacy of precision, beauty, and profound intelligence that continues to inspire and resonate. He was, in essence, the architect who synthesized the elements of Cubism into a coherent and enduring vision.