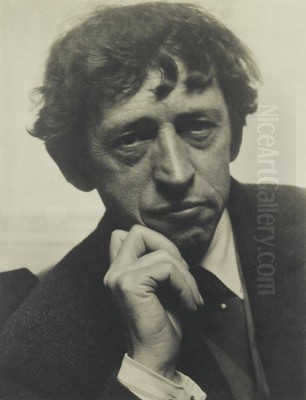

John Marin stands as a towering figure in the landscape of American art, a key pioneer who navigated the turbulent currents of early 20th-century modernism. Primarily celebrated for his vibrant watercolors, though also a master of oils and etching, Marin forged a unique visual language. His work captured the pulsating energy of urban life, particularly Manhattan, and the raw, elemental forces of nature, most famously the rugged coast of Maine. Deeply connected to the influential circle of photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, Marin translated European avant-garde ideas into a distinctly American idiom, leaving an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

John Marin was born on December 23, 1870, in Rutherford, New Jersey. Following the early death of his mother, he spent much of his childhood in Weehawken, New Jersey, raised by maternal grandparents and two aunts. His initial career path was not in fine art but in architecture. He worked for several years as an architectural draftsman, an experience that likely honed his sense of structure and line, elements that would become crucial in his later artistic endeavors.

However, the pull towards fine art proved irresistible. Marin eventually abandoned architecture to pursue painting more seriously. He sought formal training, enrolling first at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, one of the oldest and most respected art institutions in the United States. Following his time at PAFA, he continued his studies at the Art Students League of New York, further immersing himself in the techniques and theories of painting and drawing. This foundational period provided him with the technical skills upon which he would build his innovative style.

European Sojourn and the Stieglitz Connection

Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Marin felt the need to experience European art firsthand. In 1905, he embarked on a transformative journey abroad, spending significant time in Paris, the epicenter of the art world. This period was crucial for his development. He absorbed the influences of various masters, both historical and contemporary. Artists like Albrecht Dürer and James McNeill Whistler left their mark, but it was the exposure to modern movements that proved most decisive.

In Paris, Marin encountered the radical innovations of artists associated with Fauvism and Cubism. The structural explorations of Paul Cézanne and the expressive color of Henri Matisse resonated deeply, even if Marin later downplayed direct allegiance to specific Parisian trends. He also admired the sculptural power of Auguste Rodin. During this formative European period, Marin produced etchings that gained him some early recognition. More significantly, it was in Paris that he met the photographer and visionary art promoter Alfred Stieglitz. This encounter marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship and professional association that would be instrumental in shaping Marin's career.

Stieglitz recognized Marin's unique talent and potential. Upon Marin's return to the United States around 1909-1910, Stieglitz became his staunchest advocate. He began exhibiting Marin's work at his influential gallery, initially known as the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later simply as "291" after its address on Fifth Avenue. This gallery was a crucial hub for introducing European modernism to America and for championing avant-garde American artists.

Forging a Modernist Path in America

Stieglitz provided Marin with his first solo exhibition at "291" in 1909. This marked a significant step in establishing Marin's reputation within the nascent American modernist scene. Stieglitz continued to support Marin consistently, organizing nearly annual exhibitions of his work for decades, providing both financial stability and critical visibility. Marin became a central figure within the Stieglitz circle, a group that included other groundbreaking artists like Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley.

A pivotal moment for Marin, and for American art in general, was his participation in the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show. Held in New York City, Chicago, and Boston, this landmark exhibition introduced American audiences on a large scale to the radical developments in European art, including works by Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and Duchamp. Marin exhibited several watercolors, and his inclusion solidified his position as a leading American modernist, gaining him wider recognition and critical attention.

Marin's Distinctive Artistic Style

John Marin's art is characterized by its dynamism, energy, and a unique synthesis of observation and abstraction. He sought to capture not just the appearance of his subjects, but their underlying forces and rhythms. His style drew from various sources but remained highly personal. Elements of Cubism are evident in his fractured planes and geometric structures, particularly in his cityscapes. Fauvist principles can be seen in his bold, often non-naturalistic use of color to convey emotion and energy.

Marin also acknowledged the legacy of earlier American artists, particularly the watercolor techniques of Winslow Homer. However, he pushed the medium far beyond Homer's realism. Marin treated watercolor with unprecedented freedom, using rapid brushstrokes, transparent washes, and stark lines to create a sense of immediacy and vibrancy. He often left areas of the paper untouched, allowing the white ground to contribute to the overall luminosity and structure of the composition.

His approach involved a delicate balance between representation and abstraction. While his subjects – whether the skyscrapers of New York or the seascapes of Maine – are usually recognizable, they are transformed through his expressive interpretation. He famously spoke of the "warring, pushing, pulling forces" he perceived in the world and sought to translate this dynamic tension onto paper or canvas. His compositions often feature internal "frames" or energetic lines that seem to contain or unleash the forces within the scene.

Iconic Subjects: The Pulse of Manhattan

New York City was a recurring and vital subject for Marin throughout his career. He was fascinated by the city's verticality, its relentless energy, and its modern structures. His depictions of Manhattan skyscrapers, bridges like the Brooklyn Bridge, and bustling street scenes are among the most iconic images of the city in early 20th-century art. He didn't just paint buildings; he painted the feeling of the city – its cacophony, its soaring ambition, its structural power.

In works depicting the Woolworth Building or the downtown skyline, Marin employed tilted perspectives, fragmented forms, and explosive lines to convey the dynamism and overwhelming scale of the modern metropolis. His cityscapes are not static architectural renderings but vibrant, almost living entities, capturing the spirit of a rapidly changing urban landscape. His watercolor Weehawken, now in the Huntington Museum of Art, exemplifies his early engagement with urban themes viewed from his New Jersey roots, rendered with characteristic abstraction and energy.

Iconic Subjects: The Elemental Coast of Maine

From 1914 onwards, Marin began spending his summers in Maine, a practice that would continue for the rest of his life. The rugged coastline, the turbulent sea, the resilient pine trees, and the ever-changing weather provided him with an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Maine became as central to his artistic identity as Manhattan. He was encouraged to explore the region by fellow artist Ernest Haskell.

His Maine watercolors and oils capture the raw power and beauty of the natural world. He painted crashing waves, rocky shores, sailboats navigating choppy waters, and the distinctive forms of the region's islands and mountains. Works like The White Moon, Sailboat (1922) showcase his ability to convey the atmosphere and movement of the sea with remarkable economy and expressiveness. Marin Isle, Maine (1926), an oil painting, demonstrates his engagement with the specific character of the Maine landscape.

His deep connection to Maine culminated in his later years when he settled more permanently in Cape Split, Addison, Maine. Here, surrounded by the nature he loved, he continued to paint with vigor. His late works, such as those depicting the Tunk Mountains, often show an even greater freedom, with looser brushwork and sometimes thicker application of paint (impasto), exploring the textures and enduring spirit of the landscape. The painting Pine Tree, held by the Brooklyn Museum, is a powerful example of his ability to distill the essence of a natural form into a dynamic, abstract statement.

Mastery of Watercolor

While Marin worked proficiently in oil and etching, he is perhaps most renowned for his mastery of watercolor. He elevated the medium, often considered secondary to oil painting, to a primary vehicle for modernist expression. He exploited watercolor's transparency and fluidity to achieve effects of light, movement, and atmosphere that were perfectly suited to his dynamic vision.

His technique was often unconventional. He applied washes quickly, allowed colors to bleed together, and used bold, calligraphic lines to define forms and convey energy. He wasn't afraid to let the process show, embracing drips, blots, and the texture of the paper itself as integral parts of the artwork. For Marin, watercolor was not just a tool for sketching or recording appearances; it was a medium capable of capturing the vital forces and emotional resonance of his subjects. His innovations significantly influenced the perception and use of watercolor by subsequent American artists.

Exploration in Oil and Printmaking

Although best known for watercolors, Marin also produced a significant body of work in oil painting. His oils often share the same dynamic energy and semi-abstract qualities as his watercolors, but the different medium allowed for greater exploration of texture, layering, and color saturation. Works like Marin Isle, Maine and his later landscapes demonstrate his command of oil paint, often applied with vigorous brushwork and sometimes built up into thick impasto surfaces, as seen in pieces like Tunk Mountains.

Marin was also an accomplished printmaker, particularly skilled in etching. His early European etchings, influenced by Whistler, already showed his talent for line and composition. Throughout his career, he continued to explore printmaking, using etching to translate his characteristic energy and abstract tendencies into black and white. These prints, like his paintings, often focused on urban scenes and seascapes, capturing their essential structures and dynamism through intricate networks of lines.

Personality and Artistic Philosophy

Accounts describe John Marin as a generally gentle and sociable individual, though perhaps somewhat reserved or even avoidant when faced with conflict or pressure. His letters reveal a thoughtful and articulate mind, deeply engaged with the process and meaning of his art. He possessed an intense passion for his work and a profound connection to his subjects, particularly the natural world.

His artistic philosophy centered on capturing the inherent life and energy – the "elemental consideration" – of his subjects. He believed that art should express the underlying forces and rhythms, the "big forms" and "great movements," rather than merely imitating surface appearances. He famously wrote about wanting his paintings to look "like forces" and spoke of hearing the "music" or sounds of the landscape while painting, as suggested by his descriptions of works like The Blue Sea, where bold lines convey the crashing sound and impact of waves. He saw true art as existing in the realm of pure abstraction, something felt and expressed rather than scientifically explained.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Marin's career was deeply intertwined with the network of artists and patrons surrounding Alfred Stieglitz. His relationship with Stieglitz was paramount, providing crucial support and exhibition opportunities. Within this circle, he interacted with and exhibited alongside other major figures of American modernism, including Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Charles Demuth. While each pursued their own distinct path, they shared a commitment to forging an American modern art, often drawing inspiration from the American landscape and experience.

His European experience brought him into contact with the ideas of Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Braque, and Rodin, whose work fundamentally shifted the course of Western art. While Marin absorbed these influences, he integrated them into a highly personal style, resisting categorization within any single European movement. His connection with Winslow Homer represents a link to an earlier generation of American painting, particularly in the realm of watercolor, though Marin radically modernized the medium. His friendship with Ernest Haskell played a practical role in directing his attention to the fruitful subject matter of Maine.

Influence and Enduring Legacy

John Marin's impact on American art is significant and multifaceted. As one of the first American artists to consistently explore abstraction, he helped pave the way for later movements. His emphasis on dynamic energy, gestural brushwork, and the expressive potential of color and line provided a crucial precedent for the Abstract Expressionists who emerged in the 1940s and 1950s. Artists like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, while developing their own unique styles, worked in a climate shaped by the innovations of pioneers like Marin.

His elevation of watercolor to a major expressive medium had a lasting effect on American art. He demonstrated its potential for capturing immediacy, light, and dynamism in a way that resonated with the modernist spirit. His unique fusion of European avant-garde principles with distinctly American subjects – the skyscraper and the rugged coastline – helped define American modernism itself.

Marin received considerable recognition during his lifetime. Beyond the consistent support of Stieglitz and numerous exhibitions, he was honored with major museum retrospectives, including one at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1936. His stature was further acknowledged through honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from institutions such as the University of Maine and Yale University. He died on October 1, 1953, at his home in Cape Split, Maine, leaving behind a rich and influential body of work.

Major Exhibitions and Collections

Throughout his long career, John Marin's work was featured in numerous important exhibitions. Starting with his debut at Stieglitz's "291" gallery in 1909 and his inclusion in the 1913 Armory Show, he remained a consistent presence in the American art scene. Key moments included the major MoMA retrospective in 1936 and another significant retrospective at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco in 1949. His work continued to be celebrated posthumously, included in exhibitions at institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art in the 1970s and more recently, such as a 2023 exhibition at the Addison Gallery of American Art focusing on his later period (1933-1953). A documentary, Let the Canvas Be Free!, further explored his life and work in 2024.

Today, John Marin's paintings and prints are held in the permanent collections of virtually every major American art museum, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum (home to Pine Tree), the National Gallery of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Phillips Collection, and the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens (holding Weehawken). A substantial archive of his work and papers was donated by his son, John Marin Jr., to the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, in 1987, ensuring his legacy is preserved for future study. Further donations were made to institutions like the Yale University Art Gallery and Colby College Museum of Art.

Conclusion

John Marin remains a pivotal figure in American art history. He was a bridge between European modernism and a distinctly American artistic identity. Through his dynamic watercolors, oils, and etchings, he captured the vibrant energy of the modern city and the elemental power of the natural world with unparalleled force and originality. His commitment to expressing the underlying rhythms and structures of his subjects, his mastery of multiple media, particularly watercolor, and his influential role within the Stieglitz circle solidify his status as a foundational modernist. Marin's vision continues to resonate, offering a powerful and enduring perspective on the American scene in the early 20th century.