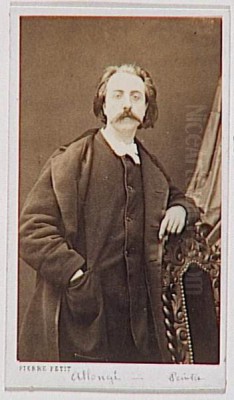

Auguste Allongé, a distinguished French artist of the 19th century, carved a unique niche for himself through his profound mastery of charcoal drawing and his evocative landscape paintings. Born in Paris on March 19, 1833, Allongé's artistic journey saw him transition from the conventional path of historical painting to become one of the most celebrated proponents of charcoal as a finished medium, deeply influencing the perception and application of this humble tool. His life and work are intertwined with the spirit of the Barbizon School, capturing the subtle poetry of the French countryside with sensitivity and technical brilliance.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Paris, the vibrant artistic heart of 19th-century Europe, was the cradle of Auguste Allongé's artistic aspirations. Growing up in this bustling metropolis, he was inevitably exposed to a rich tapestry of artistic influences and the rigorous academic traditions that shaped many artists of his era. His innate talent led him to seek formal training, a crucial step for any aspiring artist wishing to make their mark.

At the age of twenty, in 1853, Allongé enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the premier institution for art education in France. Here, he studied under the tutelage of respected masters such as Léon Cogniet and Louis-Charles-Auguste Ducornet. Cogniet was known for his historical and portrait paintings, instilling in his students a strong foundation in drawing and composition. Ducornet, despite being born without arms and painting with his feet, was a figure of immense determination and skill, specializing in biblical and historical scenes. This academic environment emphasized classical ideals and meticulous technique. During his time at the École, Allongé also benefited from the guidance of Albert Gabriel Rigolot for landscape painting, an influence that would prove significant in his later career. His dedication and skill were recognized early on when he was awarded a gold medal by the institution in 1853, a testament to his burgeoning talent.

The Pivotal Shift: From History to Landscape

Initially, like many of his peers trained in the academic tradition, Allongé explored historical painting. This genre was highly esteemed at the time, often depicting grand narratives from mythology, religion, or history, and was considered the pinnacle of artistic achievement by the Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. However, Allongé's artistic inclinations began to steer him in a different direction.

A growing movement towards naturalism and a deeper appreciation for the native landscape was taking root in French art. Artists were increasingly venturing out of their studios to observe and depict the world around them with greater fidelity. Allongé found himself drawn to the quiet beauty and atmospheric subtleties of the French countryside. This shift marked a significant turning point in his career, leading him away from the grand narratives of history painting towards the more intimate and personal expression found in landscape art. It was in the depiction of nature that Allongé would find his true voice and make his most lasting contributions.

Embracing the Barbizon Spirit

Allongé's artistic development coincided with the flourishing of the Barbizon School, a movement of painters who gathered in and around the village of Barbizon, near the Forest of Fontainebleau. These artists, including luminaries like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, rejected the idealized landscapes of academic tradition. Instead, they sought a more direct, honest, and unembellished portrayal of nature.

The Barbizon painters emphasized keen observation, often sketching outdoors (en plein air) to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, though many, like Allongé with his charcoals, would complete their works in the studio. They were interested in the rustic charm of rural life, the grandeur of ancient forests, and the tranquil beauty of rivers and ponds. Allongé's work deeply resonates with this ethos. He shared their reverence for nature and their commitment to capturing its authentic character. His landscapes, particularly his charcoal drawings, exhibit a profound sensitivity to the nuances of light and shadow, the textures of bark and foliage, and the overall mood of a scene, placing him firmly within the spiritual, if not always geographical, orbit of the Barbizon tradition. His choice of Bourron-Marlotte, a village near Barbizon, as his place of death further underscores this connection.

The Art of "Le Fusain": Elevating Charcoal Drawing

While Allongé also worked in oils, it was his mastery of charcoal (fusain in French) that truly set him apart and secured his reputation. In the 19th century, charcoal was predominantly considered a preliminary sketching tool, used for studies or cartoons for larger paintings. Few artists regarded it as a medium capable of producing finished, exhibition-worthy artworks. Allongé was a pioneer in challenging this perception.

He recognized the unique expressive potential of charcoal – its ability to create a wide range of tones, from the deepest blacks to the most delicate grays, its suitability for rendering both precise lines and soft, atmospheric effects. He developed a sophisticated technique, using various grades of charcoal, stumping tools (estompes), erasers, and even breadcrumbs to manipulate the medium with extraordinary finesse. His charcoal drawings were not mere sketches but fully realized works of art, characterized by their rich tonal values, meticulous detail, and profound atmospheric depth.

In 1873, Allongé published his seminal treatise, "Le Fusain" (Charcoal Drawing). This book was more than just a technical manual; it was a passionate advocacy for charcoal as a legitimate artistic medium. In it, he detailed his methods, shared his insights, and encouraged other artists to explore the possibilities of fusain. The book was immensely successful, translated into several languages, and played a crucial role in popularizing charcoal drawing across Europe and America. Artists like Léon Lhermitte, also renowned for his charcoal and pastel depictions of rural life, benefited from and contributed to this elevation of drawing media. Allongé's efforts helped to dignify charcoal, demonstrating that it could convey artistic vision with the same power and subtlety as oil paint or watercolor.

Signature Works and Stylistic Hallmarks

Auguste Allongé's oeuvre is rich with landscapes that capture the serene beauty of the French countryside, particularly the forests, rivers, and rural scenes that he so loved. His works are characterized by a remarkable sensitivity to light and shadow, a delicate rendering of natural forms, and an ability to evoke a palpable sense of atmosphere.

Among his notable works, pieces like Solitude (Fontainebleau Forest) exemplify his connection to the Barbizon spirit, depicting the majestic tranquility of the ancient woods. View of the Seine near Rouen showcases his skill in capturing the reflective qualities of water and the interplay of light on a broader landscape. Works often titled Paysage (Landscape), such as the charcoal from 1870, or Linwood Landscape (Woodland Landscape), highlight his consistent focus. Other pieces, such as Forest Floor and a River (1868), A Path through the Forest, near Bayeux (circa 1860-1890), Paysage à la mare (Landscape with a Pond, 1898), and Bord de rivière (Riverbank, 1868), all demonstrate his ability to find beauty in the seemingly ordinary aspects of nature.

His charcoal drawings, in particular, reveal his mastery. He used the medium to create a rich tapestry of textures – the rough bark of trees, the delicate tracery of leaves, the soft haze of a distant horizon. He understood that line alone, without color, could convey immense depth and emotion. His compositions are often carefully balanced, drawing the viewer's eye into the scene and creating a sense of immersion. Whether depicting a sun-dappled forest interior, a misty riverbank, or a solitary tree standing against the sky, Allongé's works possess a quiet poetry and a profound respect for the natural world. The work La Mer à Porrières (The Sea at Porrières, 1868) also stands out, showing his versatility in depicting different natural environments with his signature charcoal technique.

A Teacher and Mentor: Passing on the Craft

Beyond his personal artistic production, Auguste Allongé was also a dedicated teacher. In 1896, he established an art studio at Passage Stanislas, No. 6, in Paris, where he taught landscape painting. He was keen to share his knowledge and passion, particularly his expertise in charcoal drawing, with a new generation of artists.

One of his notable students was Charles Bornert-Legueule (sometimes recorded as Charles Bornait-Legueuleux), who went on to become a recognized artist in his own right, likely carrying forward some of the principles learned from his master. Allongé's influence as an educator was significantly amplified by his book, "Le Fusain," which reached a far wider audience than his direct students.

Furthermore, Allongé was an important collaborator for illustrated journals such as L'Illustration and Le Monde illustré. In an era before widespread photography, such publications relied heavily on artists to provide images for news stories, travelogues, and literary pieces. Allongé's skill in creating evocative and detailed landscape drawings made him a valuable contributor, and his work in these popular magazines helped to disseminate his style and further popularize landscape art among the general public.

Allongé and His Contemporaries: Navigating the Parisian Art World

Auguste Allongé navigated a dynamic and rapidly evolving art world in 19th-century Paris. He was part of a generation that witnessed the decline of strict academicism and the rise of various new artistic movements, from Realism to Impressionism. While firmly rooted in the Barbizon tradition, his career overlapped with these transformative changes.

He is known to have frequented Antony's tavern (Auberge Antony) in Bourron-Marlotte, a gathering place for artists. Here, he would have interacted with figures like Édouard Manet, a pivotal artist who bridged Realism and Impressionism, and Armand Charnay, another landscape painter. Such interactions provided a fertile ground for the exchange of ideas and artistic camaraderie.

While the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, were pushing the boundaries of landscape painting with their focus on capturing the fleeting effects of light and color through broken brushwork, Allongé remained more aligned with the tonal subtleties and detailed rendering characteristic of the Barbizon approach. However, his emphasis on direct observation of nature and the importance of light effects certainly shared common ground with the broader artistic currents of his time. Other landscape artists like Henri Harpignies, who also had strong Barbizon leanings and worked extensively in watercolor and occasionally charcoal, represent a similar dedication to the French landscape. Even earlier figures like Georges Michel, known for his dramatic, pre-Romantic landscapes of the Parisian outskirts, laid some groundwork for the appreciation of local scenery that Allongé and the Barbizon painters championed.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Collections

Auguste Allongé's talent did not go unnoticed during his lifetime. He regularly exhibited his works at the prestigious Paris Salon, the most important venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. His participation in the Salon was a mark of professional achievement, and he received accolades for his submissions, including a medal in 1855, which further solidified his standing in the art community. This award, distinct from his earlier École des Beaux-Arts medal, specifically recognized his exhibited works.

His paintings and charcoal drawings were sought after by collectors both in France and internationally. Evidence of his international reach can be found in the inclusion of his works in collections far from Paris. For instance, the O'Higginiano y Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Talca, Chile, holds examples of his landscape paintings, indicating an appreciation for his art in South America. His works also found their way into private collections in the United States, demonstrating a transatlantic appeal. The presence of his art in such diverse locations speaks to the universal appeal of his sensitive portrayals of nature. Auction records, such as the sale of Paysage à la mare (1898) and the appearance of Bord de rivière (1868) at sales, continue to attest to the enduring market for his work.

Personal Life and Final Years

In August 1874, Auguste Allongé married Amélie Williams, a poet. This union brought together two creative individuals, and one can imagine a shared appreciation for the beauty and expressiveness found in both art and literature. Details about their life together are not extensively documented, but it is plausible that Amélie's poetic sensibilities resonated with Auguste's artistic vision.

Allongé continued to work and teach, remaining dedicated to his art throughout his life. He spent his final years in Bourron-Marlotte, a village intimately associated with the Barbizon painters, located near the Forest of Fontainebleau. This choice of residence in his later life underscores his deep connection to the landscapes that had inspired so much of his work. Auguste Allongé passed away in Bourron-Marlotte on July 4, 1898, leaving behind a significant body of work and a legacy as a master of charcoal and a sensitive interpreter of the French landscape.

Enduring Legacy: The Quiet Poetry of Nature

Auguste Allongé's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as a key figure in the popularization and elevation of charcoal drawing, transforming it from a preparatory tool into a respected medium for finished artworks. His influential treatise, "Le Fusain," educated and inspired countless artists, contributing to a broader appreciation for the graphic arts. Artists like Maxime Lalanne, also a proponent of charcoal and etching, shared this dedication to the medium's expressive power.

As a landscape artist, Allongé captured the quiet poetry of the French countryside with a distinctive blend of Barbizon naturalism and refined technique. His works evoke a deep sense of place and atmosphere, inviting viewers to connect with the serene beauty of nature. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his Impressionist contemporaries like Berthe Morisot or Edgar Degas (who also explored various media), Allongé's contribution lies in his mastery of his chosen medium and his consistent dedication to a particular vision of landscape art. His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent artists who continued to explore the expressive possibilities of charcoal and to find inspiration in the natural world. His contemporary, Adolphe Appian, similarly excelled in both etching and charcoal landscapes, often with a melancholic, atmospheric quality.

Conclusion

Auguste Allongé stands as a significant artist of 19th-century France, a master whose delicate yet powerful charcoal drawings and evocative landscape paintings continue to resonate with audiences today. He successfully bridged the gap between academic tradition and the burgeoning naturalist movements, finding his unique voice in the depiction of the French landscape and in his pioneering advocacy for charcoal as a fine art medium. His dedication to his craft, his influential teachings, and the timeless beauty of his art ensure his enduring place in the annals of art history. Through his work, the subtle moods and enduring charm of the forests, rivers, and fields of France are preserved with an artist's loving and skillful hand.