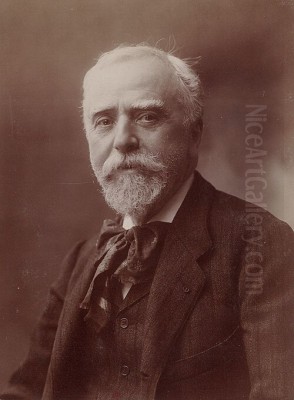

Léon Augustin Lhermitte stands as a significant figure in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French art. Born on July 31, 1844, in Mont-Saint-Père, a village in the Aisne region of France, and passing away in Paris on July 28, 1925, Lhermitte dedicated his long and prolific career primarily to the depiction of French rural life. He became renowned for his sensitive and dignified portrayals of peasants and agricultural labourers, capturing the rhythms, hardships, and quiet nobility of their existence. Working predominantly within the Naturalist and Realist traditions, Lhermitte masterfully employed oil paint, pastel, charcoal, and etching to bring his visions of the French countryside to life, earning widespread acclaim and leaving an indelible mark on the art of his time.

His work serves as a vital bridge between the Barbizon School's romanticized view of nature and the burgeoning modern movements, incorporating subtle influences from Impressionism while retaining a strong foundation in academic draftsmanship. Lhermitte's art offers a profound and enduring window into a world undergoing significant social and economic change, celebrating the enduring connection between humanity and the land.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Léon Lhermitte's origins were modest. Born in the rural setting of Mont-Saint-Père, his father was a village schoolteacher. This environment undoubtedly shaped his lifelong affinity for the countryside and its inhabitants. From a young age, Lhermitte displayed a remarkable talent for drawing, an aptitude that did not go unnoticed. Encouraged by his family and local patrons, his artistic inclinations were nurtured. The landscapes and people of the Aisne region provided his earliest subjects, instilling in him a deep observational connection to the natural world and the cycles of agricultural life.

Recognizing that his talent required formal training and exposure to the wider art world, Lhermitte made the pivotal move to Paris in 1863. At the age of nineteen, he arrived in the bustling capital, the undisputed centre of the European art world, ready to immerse himself in study and forge his artistic path. This transition from the quiet countryside to the dynamic urban environment marked the beginning of his professional artistic journey.

Formative Years: The Petite École and Lecoq de Boisbaudran

In Paris, Lhermitte enrolled at the École Impériale de Dessin, often referred to as the Petite École (distinct from the more prestigious École des Beaux-Arts). This institution focused on training artists for the decorative arts but provided a solid grounding in drawing. Crucially, Lhermitte came under the tutelage of Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, a highly influential and unconventional teacher. Lecoq de Boisbaudran championed a unique pedagogical method centred on visual memory training – teaching students to observe a subject intently and then reproduce it from memory, emphasizing capturing the essential form and character rather than relying solely on direct copying.

This training proved immensely beneficial for Lhermitte, honing his already keen observational skills and enabling him to render scenes with remarkable accuracy and vitality, even when working later in the studio. At the Petite École, he formed lasting friendships with fellow students who would also achieve artistic recognition, including Henri Fantin-Latour, Alphonse Legros, and Jean-Charles Cazin. The rigorous training under Lecoq de Boisbaudran, who also counted Auguste Rodin among his pupils, provided Lhermitte with the technical foundation upon which he would build his successful career.

Debut and Early Success: The Power of Charcoal

Lhermitte made his public debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1864, not with a painting, but with a charcoal drawing titled The Banks of the Marne near Alfort (Bords de la Marne près d'Alfort). The Salon was the official, state-sponsored exhibition and the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. For a young artist to be accepted was a significant achievement, and Lhermitte's charcoal work garnered positive attention. Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, he continued to exhibit charcoal drawings, establishing a strong reputation for his mastery of the medium.

His charcoals were praised for their atmospheric depth, subtle tonal gradations, and evocative portrayal of landscapes and rural scenes. This early success in a graphic medium demonstrated his exceptional draftsmanship, a skill that would underpin all his subsequent work in pastel and oil. His rising prominence also led to connections with influential figures in the art market, including the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who would later become famous for championing the Impressionists but also handled works by more established artists like Lhermitte.

The Heart of Lhermitte's Art: Naturalism and Rural Life

Lhermitte is most closely associated with the Naturalist movement, which emerged in France in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Naturalism sought to depict subjects with objective truthfulness, often focusing on everyday life, particularly that of the working classes and rural populations. It shared roots with Realism, championed earlier by Gustave Courbet, but often presented its subjects with less overt social commentary and a greater emphasis on atmosphere and the integration of figures within their environment.

Lhermitte's work clearly shows the influence of the Barbizon School painters, who worked in the decades preceding him. Artists like Jean-François Millet and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot had pioneered the sympathetic depiction of peasant life and landscape, moving away from idealized historical or mythological scenes. Lhermitte admired Millet deeply, and echoes of Millet's monumental figures and themes of rural labour resonate in Lhermitte's own work. However, Lhermitte developed his own distinct approach, often imbuing his scenes with a greater sense of light and sometimes a more picturesque quality than the often starker realism of Courbet or the solemn gravity of Millet. Other Barbizon figures like Théodore Rousseau and Charles-François Daubigny also contributed to the artistic climate that valued direct observation of nature, which Lhermitte embraced.

Bridging Traditions: Realism and Impressionistic Light

While firmly rooted in the Realist and Naturalist traditions, Lhermitte was not immune to the artistic innovations happening around him, particularly the rise of Impressionism in the 1870s and 1880s. Although he never became an Impressionist himself – maintaining a commitment to solid drawing, detailed rendering, and often a more finished surface – his work demonstrates an absorption of certain Impressionist concerns, especially their fascination with capturing the effects of natural light and atmosphere.

His later paintings and pastels, in particular, often feature a brighter palette and a more nuanced handling of light than his earlier works. He became adept at rendering the shimmering quality of sunlight on fields, the dappled light under trees, or the specific atmospheric conditions of different times of day. This sensitivity to light distinguishes his work from some of the more academic painters of his generation. Interestingly, the Impressionist Edgar Degas, known for his own experiments with light and composition, respected Lhermitte's work and reportedly invited him to participate in one of the Impressionist exhibitions. Lhermitte declined, preferring to remain within the established Salon system, but the connection highlights the cross-currents between different artistic circles of the era. His path differed significantly from core Impressionists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, or Camille Pissarro, who prioritized capturing fleeting moments and sensations over detailed narrative or finish.

Themes of Labor and the Land

The central and recurring theme throughout Lhermitte's oeuvre is the life and labour of the French peasant. He returned again and again to scenes of harvesting, haymaking, gleaning, potato digging, and market days. His depictions are characterized by a sense of dignity and respect for his subjects. He portrayed the physical demands of agricultural work but often emphasized the communal aspects, the connection to the seasons, and the quiet endurance of the rural population.

Works depicting harvesters resting for a meal, families working together in the fields, or women gathering leftover grain (gleaning) are iconic representations of his focus. Unlike some social realists who might emphasize the brutal aspects of poverty, Lhermitte often presented rural life in a somewhat idealized, yet fundamentally truthful, light. His paintings captured the specific tools, clothing, and customs of the regions he knew, serving as valuable visual documents of a way of life that was gradually being transformed by modernization and migration to cities during the French Third Republic. His focus on these themes aligned him with other painters of rural life, such as Jules Breton, who also found success depicting similar subjects.

Spiritual Dimensions: Religious Themes

While best known for his scenes of agricultural labour and landscapes, Lhermitte also explored religious themes throughout his career. This aspect of his work is less frequently discussed but forms a consistent thread. He produced paintings depicting church interiors, often focusing on the play of light through stained-glass windows or the quiet devotion of worshippers. Scenes related to Catholic rituals, such as First Communion or families at prayer, appear in his oeuvre.

He also undertook commissions for church decorations and created illustrations for religious texts. One notable later work, The Friend of the Humble (Supper at Emmaus) (1892), transposes a biblical scene into a contemporary peasant setting, a common practice among nineteenth-century artists seeking to make religious narratives more immediate and relevant. These works reflect both the enduring importance of religion in rural French society and Lhermitte's own capacity to handle themes of faith and spirituality with sensitivity.

Mastery Across Media

Lhermitte's technical proficiency extended across several media, each exploited for its unique expressive potential.

Charcoal

As noted, Lhermitte first gained significant recognition through his charcoal drawings. He possessed an exceptional ability to manipulate this medium, achieving a wide range of tones from deep, velvety blacks to delicate, atmospheric greys. His charcoals were not merely preparatory sketches but finished works of art, valued for their painterly qualities and evocative power. He used charcoal to capture the structure of landscapes, the solidity of figures, and the subtle effects of light and shadow with remarkable finesse. His early mastery set a high standard for graphic work exhibited at the Salon.

Pastel

From the 1880s onwards, Lhermitte increasingly turned to pastel, becoming one of its most celebrated practitioners in France. Pastel, with its pure, vibrant pigments and powdery texture, was perfectly suited to his interest in capturing luminous effects and delicate colour harmonies. He used pastels for both finished works and studies, often achieving a richness and brilliance comparable to oil painting. His pastel works depicting peasant women, children, and sunlit interiors are particularly admired for their tenderness and technical virtuosity. His skill rivalled that of other contemporary masters of the medium, such as Degas or the American expatriate Mary Cassatt.

Oil Painting

Lhermitte produced numerous large-scale oil paintings intended for the Salon. These works often tackled ambitious multi-figure compositions depicting key moments in the agricultural calendar, such as Paying the Harvesters. His oil technique combined the solid drawing and careful modelling learned in his academic training with the brighter palette and attention to light influenced by his engagement with Naturalism and Impressionism. While perhaps less spontaneous than his pastels, his oil paintings possess a commanding presence and narrative clarity that cemented his official reputation.

Etching

Lhermitte also worked as an etcher, translating many of his popular painted and drawn compositions into prints. Etching allowed for wider dissemination of his images and showcased his skill in linear expression. His participation in this medium connected him to the etching revival movement that gained momentum in France during the latter part of the nineteenth century, championed by artists and publishers seeking to elevate printmaking as a fine art form.

Signature Works: Icons of Rural France

Several of Lhermitte's works have become iconic representations of French rural life and stand as highlights of his career.

Paying the Harvesters (La Paye des Moissonneurs) (1882)

Arguably Lhermitte's most famous painting, this large-scale work (now housed in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris) depicts a group of weary harvesters gathering at the end of the day to receive their wages from the landowner or foreman. The central figure is a powerful man with a scythe, embodying the strength and toil of agricultural labour. The painting is remarkable for its detailed rendering, complex composition, and masterful handling of the warm, late-afternoon light. It was exhibited at the Salon of 1882 to great acclaim, solidifying Lhermitte's status as a leading painter of rural themes.

The Gleaners (Les Glaneuses) (1887)

This subject, famously treated by Millet three decades earlier, was revisited by Lhermitte in a major pastel (now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art). Gleaning – the practice of collecting leftover grain after the harvest – was traditionally reserved for the poorest members of the rural community, often women and children. Lhermitte's depiction, while acknowledging the poverty implied by the activity, presents the figures with grace and dignity, set against a luminous, expansive landscape under a vast sky. It showcases his mastery of the pastel medium and his ability to imbue a scene of hardship with poetic beauty.

The Harvest (La Moisson)

Lhermitte painted numerous variations on the theme of the harvest throughout his career, in oil, pastel, and charcoal. These works capture different moments of this crucial agricultural activity – the cutting of the grain, the binding of sheaves, the midday rest. They consistently demonstrate his deep understanding of the rhythms of farm work and his ability to render the golden light and heat of the summer fields.

The Friend of the Humble (Supper at Emmaus) (1892)

This significant religious painting (now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) depicts the biblical story of Christ revealing himself to two disciples after his resurrection. Lhermitte sets the scene inside a humble peasant cottage, with Christ and the disciples sharing a simple meal. The naturalistic setting and the depiction of Christ as a contemporary figure make the sacred event feel immediate and relatable, reflecting a trend in religious art of the period.

Washerwomen (Les Laveuses)

Another recurring theme was that of women washing clothes in rivers or communal washhouses. These scenes allowed Lhermitte to explore the play of light on water, the textures of wet fabric, and the camaraderie among the women engaged in this laborious task. Works like The Moated Wall or the later pastel Three Washerwomen (1917) exemplify his sensitive treatment of this subject.

Critical Acclaim and Recognition

Lhermitte enjoyed considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His regular participation in the Paris Salon brought him numerous awards, including a third-class medal in 1874 (for a work titled La Moisson) and a second-class medal in 1880. His reputation was further enhanced by prestigious official honours: he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1884 and promoted to Officer in 1894. A crowning achievement came at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1889, where he was awarded the Grand Prix for painting, confirming his status among the elite of the French art establishment.

Beyond official accolades, Lhermitte's work was admired by fellow artists, critics, and collectors. Perhaps the most famous testament to his contemporary reputation comes from Vincent van Gogh. In letters to his brother Theo, Van Gogh repeatedly expressed his profound admiration for Lhermitte, whom he considered a master of depicting the figure and capturing the essence of rural life. Van Gogh wrote enthusiastically about Lhermitte's black-and-white drawings published in illustrated magazines, stating, "If every month Le Monde Illustré published one of his compositions... I should be delighted... It is certain that for years I have not seen anything as beautiful as this scene by Lhermitte... I am too preoccupied by Lhermitte this evening to be able to talk of other things." Van Gogh praised Lhermitte as an absolute "master of the figure," capable of modelling and capturing human form "as he pleases." This high praise from an artist of Van Gogh's stature underscores Lhermitte's significance in the eyes of his contemporaries.

Lhermitte and His Contemporaries

Lhermitte occupied a respected position within the complex artistic landscape of late nineteenth-century France. He maintained connections with various artistic circles while carving out his own distinct path. His work acknowledged the legacy of the Barbizon painters, particularly Millet and Corot, and engaged with the Realism of Courbet, though generally with a less confrontational stance. He navigated the dominant Salon system successfully, unlike many of the Impressionists who broke away to form their own independent exhibitions.

His relationship with Impressionism was one of respectful distance; he absorbed aspects of their approach to light but maintained his commitment to traditional draftsmanship and finish. His decision not to join their exhibitions, despite Degas's invitation, highlights his alignment with more established artistic structures. Furthermore, Lhermitte was actively involved in the art institutions of his time. He was a founding member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1890. This alternative exhibiting society was formed by a group of artists (including prominent figures like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Ernest Meissonier, and Auguste Rodin) who seceded from the older Salon (then managed by the Société des Artistes Français) seeking greater artistic freedom and control over exhibitions. Lhermitte's involvement demonstrates his standing among his peers and his engagement with the organizational side of the art world.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Léon Lhermitte continued to paint actively into the twentieth century, remaining faithful to his core themes of rural life even as the art world was being revolutionized by Fauvism, Cubism, and other avant-garde movements. While his style might have seemed increasingly traditional compared to these radical developments, he retained a loyal following and continued to exhibit his work. His later works, particularly his pastels, often display a continued freshness and sensitivity.

His son, Jean Lhermitte, became a noted neurologist, but artistic talent also ran in the family; another son, Jacques, pursued art, and the Chinese text mentions a son Charles as a photographer working in a similar realist vein, suggesting a familial continuity of artistic vision. Lhermitte passed away in Paris in 1925, just three days shy of his 81st birthday, leaving behind a vast body of work.

Lhermitte's legacy endures through his powerful and empathetic depictions of French rural life. His paintings and drawings offer invaluable insights into the social history of the period and celebrate the dignity of labour. His technical mastery, particularly in pastel and charcoal, remains admired. While perhaps overshadowed in modernist art historical narratives by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, his work has consistently been held in high regard by museums and collectors. His paintings are found in major museum collections across the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and many others in Brussels, Montreal, Moscow, and beyond. He remains a key figure of French Naturalism, a chronicler of the countryside, and an artist whose work continues to resonate with its quiet beauty and profound humanity.

Conclusion

Léon Augustin Lhermitte carved a unique and enduring niche in the rich tapestry of French art. Emerging from a rural background, he dedicated his immense talent to chronicling the world he knew best – the fields, villages, and people of the French countryside. Through his masterful handling of oil, pastel, and charcoal, he captured the dignity of peasant labour, the beauty of the landscape, and the subtle effects of light and atmosphere. While rooted in the traditions of Realism and Naturalism, and influenced by the Barbizon School, he selectively incorporated lessons from Impressionism, creating a style that was both grounded and luminous. Praised by contemporaries like Van Gogh and honoured by the official art establishment, Lhermitte created a body of work that stands as a testament to a way of life, rendered with technical brilliance and deep empathy. His art remains a vital and moving portrayal of humanity's connection to the land.